Fenfluramine

Fenfluramine, formerly sold under the brand name Pondimin among others, is an appetite suppressant which was used to treat obesity and is now no longer marketed.[2] It was used both on its own and, in combination with phentermine, as part of the anti-obesity medication Fen-Phen.[2]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Pondimin, Fen-Phen (with phentermine), others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 13–30 hours[1] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.616 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H16F3N |

| Molar mass | 231.26 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Medical uses

Fenfluramine was formerly used as an appetite suppressant to treat obesity.[2] It was available both alone and in combination with phentermine, another appetite suppressant.[2]

Adverse effects

At higher therapeutic doses, headache, diarrhea, dizziness, dry mouth, erectile dysfunction, anxiety, insomnia, irritability, lethargy, and CNS stimulation have been reported with fenfluramine.[1]

There have been reports associating chronic fenfluramine treatment with emotional instability, cognitive deficits, depression, psychosis, exacerbation of pre-existing psychosis (schizophrenia), and sleep disturbances.[1][3] It has been suggested that some of these effects may be mediated by serotonergic neurotoxicity/depletion of serotonin with chronic administration and/or activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.[3][4][5][6]

Heart valve disease

The distinctive valvular abnormality seen with fenfluramine is a thickening of the leaflet and chordae tendineae. One mechanism used to explain this phenomenon involves heart valve serotonin receptors, which are thought to help regulate growth. Since fenfluramine and its active metabolite norfenfluramine stimulate serotonin receptors, this may have led to the valvular abnormalities found in patients using fenfluramine. In particular norfenfluramine is a potent inhibitor of the re-uptake of 5-HT into nerve terminals.[7] Fenfluramine and its active metabolite norfenfluramine affect the 5-HT2B receptors, which are plentiful in human cardiac valves. The suggested mechanism by which fenfluramine causes damage is through over or inappropriate stimulation of these receptors leading to inappropriate valve cell division. Supporting this idea is the fact that this valve abnormality has also occurred in patients using other drugs that act on 5-HT2B receptors.[8][9]

According to a study of 5,743 former users conducted by a plaintiff's expert cardiologist, damage to the heart valve continued long after stopping the medication.[10] Of the users tested, 20% of women, and 12% of men were affected. For all ex-users, there was a 7-fold increase of chances of needing surgery for faulty heart valves caused by the drug.[10]

Overdose

In overdose, fenfluramine can cause serotonin syndrome and rapidly result in death.[2][11]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Fenfluramine acts primarily as a serotonin releasing agent.[12][13] It increases the level of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that regulates mood, appetite and other functions.[12][13] Fenfluramine causes the release of serotonin by disrupting vesicular storage of the neurotransmitter, and reversing serotonin transporter function.[14] The drug also acts as a norepinephrine releasing agent to a lesser extent, particularly via its active metabolite norfenfluramine.[12][13] At high concentrations, norfenfluramine, though not fenfluramine, also acts as a dopamine releasing agent, and so fenfluramine may do this at very high doses as well.[12][13] In addition to monoamine release, while fenfluramine binds only very weakly to the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors, norfenfluramine binds to and activates the serotonin 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors with high affinity and the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor with moderate affinity.[15][16] The result of the increased serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission is a feeling of fullness and reduced appetite.

The combination of fenfluramine with phentermine, a norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent acting primarily on norepinephrine, results in a well-balanced serotonin–norepinephrine releasing agent with weaker effects of dopamine release.[12][13]

| Drug | NE | DA | 5-HT | Type | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fenfluramine | 739 | >10,000 | 79.3–108 | SRA | [17][12][13] |

| D-Fenfluramine | 302 | >10,000 | 51.7 | SNRA | [17][12] |

| L-Fenfluramine | >10,000 | >10,000 | 147 | SRA | [12][18] |

| Norfenfluramine | 168–170 | 1,900–1,925 | 104 | SNRA | [12][13] |

| Phentermine | 39.4 | 262 | 3,511 | NDRA | [17] |

Pharmacokinetics

The elimination half-life of fenfluramine has been reported as ranging from 13 to 30 hours.[1] The mean elimination half-lives of its enantiomers have been found to be 19 hours for dexfenfluramine and 25 hours for levfenfluramine.[2] Norfenfluramine, the major active metabolite of fenfluramine, has an elimination half-life that is about 1.5 to 2 times as long as that of fenfluramine, with mean values of 34 hours for dexnorfenfluramine and 50 hours for levnorfenfluramine.[2]

Chemistry

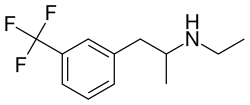

Fenfluramine is a substituted amphetamine and is also known as 3-trifluoromethyl-N-ethylamphetamine.[2] It is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers, dexfenfluramine and levofenfluramine.[2] Some analogues of fenfluramine include norfenfluramine, benfluorex, flucetorex, and fludorex.

History

Fenfluramine was developed in the early 1960s and was introduced in France in 1963.[2] Approximately 50 million Europeans were treated with fenfluramine for appetite suppression between 1963 and 1996.[2] Fenfluramine was approved in the United States in 1973.[2] The combination of fenfluramine and phentermine was proposed in 1984.[2] Approximately 5 million people in the United States were given fenfluramine or dexfenfluramine with or without phentermine between 1996 and 1998.[2]

In the early 1990s, French researchers reported an association of fenfluramine with primary pulmonary hypertension and dyspnea in a small sample of patients.[2] Fenfluramine was withdrawn from the U.S. market in 1997 after reports of heart valve disease[19][20] and continued findings of pulmonary hypertension, including a condition known as cardiac fibrosis.[21] It was subsequently withdrawn from other markets around the world. It was banned in India in 1998.[22]

Society and culture

Brand names

Fenfluramine was formerly marketed under the brand names Pondimin, Ponderax, and Adifax, among others.

Recreational use

Unlike various other amphetamine derivatives, fenfluramine is reported to be dysphoric, "unpleasantly lethargic", and non-addictive at therapeutic doses.[23] However, it has been reported to be used recreationally at high doses ranging between 80 and 400 mg, which have been described as producing euphoria, amphetamine-like effects, sedation, and hallucinogenic effects, along with anxiety, nausea, diarrhea, and sometimes panic attacks, as well as depressive symptoms once the drug had worn off.[23][24][25] At very high doses (e.g., 240 mg, or between 200–600 mg), fenfluramine induces a psychedelic state resembling that produced by lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).[25][26] Indirect (via induction of serotonin release) and/or direct activation of the 5-HT2A receptor would be expected to be responsible for the psychedelic effects of the drug at sufficient doses.

Research

Under the development code ZX008, the pharmaceutical company Zogenix is studying fenfluramine's potential to treat seizures.[27] Clinical trials have studied the use of fenfluramine in patients with Dravet syndrome.[28] Results of a phase III clinical trial showed a 64% reduction in seizures.[29]

References

- Richard C. Dart (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 874–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4. Archived from the original on 2018-05-09.

- Donald G. Barceloux (3 February 2012). Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 255–262. ISBN 978-1-118-10605-1. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018.

- James O'Donnell (Pharm. D.); Gopi Doctor Ahuja (2005). Drug Injury: Liability, Analysis, and Prevention. Lawyers & Judges Publishing Company. pp. 276–. ISBN 978-0-913875-27-8.

- Integrating the Neurobiology of Schizophrenia. Academic Press. 27 February 2007. pp. 142–. ISBN 978-0-08-047508-0.

- The Pharmacology of Corticotropin-releasing Factor (CRF). Effects on Sensorimotor Gating in the Rat. 2006. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-0-549-53661-1.

- Christian P. Muller; Barry Jacobs (30 December 2009). Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin. Academic Press. pp. 630–. ISBN 978-0-08-087817-1.

- Vickers SP, Dourish CT, Kennett GA (2001). "Evidence that hypophagia induced by d-fenfluramine and d-norfenfluramine in the rat is mediated by 5-HT2C receptors". Neuropharmacology. 41 (2): 200–9. doi:10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00063-6. PMID 11489456.

- Roth, B. L. (2007). "Drugs and Valvular Heart Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068265. PMID 17202450.

- Rothman, R. B.; Baumann, M. H. (2009). "Serotonergic Drugs and Valvular Heart Disease". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 8 (3): 317–329. doi:10.1517/14740330902931524. PMC 2695569. PMID 19505264.

- Dahl, C. F.; Allen, M. R.; Urie, P. M.; Hopkins, P. N. (2008). "Valvular Regurgitation and Surgery Associated with Fenfluramine Use: An Analysis of 5743 Individuals". BMC Medicine. 6: 34. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-6-34. PMC 2585088. PMID 18990200.

- Mann SC, Caroff SN, Keck PE, Lazarus A (20 May 2008). Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome and Related Conditions. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-1-58562-744-8.

- Rothman RB, Clark RD, Partilla JS, Baumann MH (2003). "(+)-Fenfluramine and its major metabolite, (+)-norfenfluramine, are potent substrates for norepinephrine transporters". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 305 (3): 1191–9. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.049684. PMID 12649307.

- Setola V, Hufeisen SJ, Grande-Allen KJ, Vesely I, Glennon RA, Blough B, Rothman RB, Roth BL (2003). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "Ecstasy") induces fenfluramine-like proliferative actions on human cardiac valvular interstitial cells in vitro". Mol. Pharmacol. 63 (6): 1223–9. doi:10.1124/mol.63.6.1223. PMID 12761331.

- Nestler, E. J. (2001). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience. McGraw-Hill.

- Giuseppe Di Giovanni; Vincenzo Di Matteo; Ennio Esposito (2008). Serotonin-dopamine Interaction: Experimental Evidence and Therapeutic Relevance. Elsevier. pp. 393–. ISBN 978-0-444-53235-0.

- Fitzgerald LW, Burn TC, Brown BS, Patterson JP, Corjay MH, Valentine PA, Sun JH, Link JR, Abbaszade I, Hollis JM, Largent BL, Hartig PR, Hollis GF, Meunier PC, Robichaud AJ, Robertson DW (2000). "Possible role of valvular serotonin 5-HT(2B) receptors in the cardiopathy associated with fenfluramine". Mol. Pharmacol. 57 (1): 75–81. PMID 10617681.

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Dersch CM, Romero DV, Rice KC, Carroll FI, Partilla JS (January 2001). "Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin". Synapse. 39 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 11071707.

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2002). "Therapeutic and adverse actions of serotonin transporter substrates". Pharmacol. Ther. 95 (1): 73–88. doi:10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00234-6. PMID 12163129.

- Connolly, H. M.; Crary, J. L.; McGoon, M. D.; Hensrud, D. D.; Edwards, B. S.; Edwards, W. D.; Schaff, H. V. (1997). "Valvular Heart Disease Associated with Fenfluramine-Phentermine". New England Journal of Medicine. 337 (9): 581–588. doi:10.1056/NEJM199708283370901. PMID 9271479.

- Weissman, N. J. (2001). "Appetite Suppressants and Valvular Heart Disease". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 321 (4): 285–291. doi:10.1097/00000441-200104000-00008. PMID 11307869.

- FDA September 15, 1997. FDA Announces Withdrawal Fenfluramine and Dexfenfluramine (Fen-Phen) Archived 2013-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- "Drugs banned in India". Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Dte.GHS, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Archived from the original on 2015-02-21. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- John Calvin M. Brust (2004). Neurological Aspects of Substance Abuse. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-7506-7313-6.

- United States. Congress. Senate. Select Committee on Small Business. Subcommittee on Monopoly and Anticompetitive Activities (1976). Competitive problems in the drug industry: hearings before Subcommittee on Monopoly and Anticompetitive Activities of the Select Committee on Small Business, United States Senate, Ninetieth Congress, first session. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 2–.

- Drug Addiction II: Amphetamine, Psychotogen, and Marihuana Dependence. Springer Science & Business Media. 27 November 2013. pp. 258–. ISBN 978-3-642-66709-1.

- Drug Addiction II: Amphetamine, Psychotogen, and Marihuana Dependence. Springer Science & Business Media. 27 November 2013. pp. 249–. ISBN 978-3-642-66709-1.

- "Zogenix ends enrolment in second Phase lll trial of ZX008". Drug Development Technology. Kable. 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-02-04. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "A Two-Part Study to Investigate the Dose-Ranging Safety and Pharmacokinetics, Followed by the Efficacy and Safety of ZX008 (Fenfluramine Hydrochloride) Oral Solution as an Adjunctive Therapy in Children ≥2 Years Old and Young Adults With Dravet Syndrome - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "Zogenix drug cuts seizure rate in patients with severe epilepsy". statnews.com. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

Further reading

- Welch, J. T.; Lim, D. S. (2007). "The Synthesis and Biological Activity of Pentafluorosulfanyl Analogs of Fluoxetine, Fenfluramine, and Norfenfluramine". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 15 (21): 6659–6666. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2007.08.012. PMID 17765553.