Pindolol

Pindolol, sold under the brand name Visken among others, is a nonselective beta blocker which is used in the treatment of hypertension and angina pectoris.[1][2] It is also an antagonist of the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor, preferentially blocking inhibitory 5-HT1A autoreceptors, and has been researched as an add-on therapy to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of depression.[3][4][5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Visken, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684032 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50% to 95% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 3–4 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

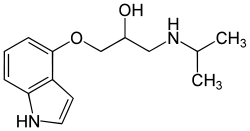

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.501 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H20N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 248.321 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Medical uses

Pindolol is used for hypertension in the United States, Canada, and Europe, and also for angina pectoris outside the United States.[2] When used alone for hypertension, pindolol can significantly lower blood pressure and heart rate, but the evidence base for its use is weak as the number of subjects in published studies is small.[2] In some countries, pindolol is also used for arrhythmias and prophylaxis of acute stress reactions.

Contraindications

Similar to propranolol with an extra contraindication for hyperthyroidism. In patients with thyrotoxicosis, possible deleterious effects from long-term use of pindolol have not been adequately appraised. Beta-blockade may mask the clinical signs of continuing hyperthyroidism or complications, and give a false impression of improvement. Therefore, abrupt withdrawal of pindolol may be followed by an exacerbation of the symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including thyroid storm.[6]

Pindolol has modest beta-adrenergic agonist activity and is therefore used with caution in angina pectoris.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 15–81 | Human | [8][9][10] |

| 5-HT1B | 4,100 34–151 | Human Rodent | [9] [7][11] |

| 5-HT1D | 4,900 | Human | [9] |

| 5-HT1E | >10,000 | Human | [12] |

| 5-HT1F | >10,000 | Human | [13] |

| 5-HT2A | 9,333 | Human | [14] |

| 5-HT2B | 2,188 | Human | [14] |

| 5-HT2C | >10,000 | Human | [14] |

| 5-HT3 | ≥6,610 | Multiple | [15][16][17] |

| 5-HT5B | >1,000 | Rat | [18] |

| 5-HT6 | >10,000 (–) | Mouse | [19] |

| 5-HT7 | >10,000 | Human | [20][21] |

| α1 | 7,585 | Pigeon | [15] |

| α2 | ND | ND | ND |

| β1 | 0.52–2.6 | Human | [10][22] |

| β2 | 0.40–4.8 | Human | [10][22] |

| β3 | 44 | Human | [22] |

| D2-like | >10,000 | Rat | [23] |

| D2 | >10,000 | Pigeon | [15] |

| D3 | >10,000 | Pigeon | [15] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Pindolol is a non-selective beta blocker or β-adrenergic receptor antagonist with partial agonist activity and also possesses intrinsic sympathomimetic activity. This means that pindolol, particularly in high doses, exerts effects like epinephrine (adrenaline) or isoprenaline (increased pulse rate, increased blood pressure, bronchodilation), but these effects are limited. Pindolol also shows membrane-stabilizing effects like quinidine, possibly accounting for its antiarrhythmic effects. It also acts as a serotonin 5-HT1A receptor weak partial agonist (intrinsic activity = 20–25%) or functional antagonist.[24]

Pharmacokinetics

Pindolol is rapidly and well absorbed from the GI tract. It undergoes some first-pass-metabolization leading to an oral bioavailability of 50-95%. Patients with uremia may have a reduced bioavailability. Food does not alter the bioavailability, but may increase the resorption. Following an oral single dose of 20 mg peak plasma concentrations are reached within 1–2 hours. The effect of pindolol on pulse rate (lowering) is evident after 3 hours. Despite the rather short halflife of 3–4 hours, hemodynamic effects persist for 24 hours after administration. Plasma halflives are increased to 3-11.5 hours in patients with renal impairment, to 7–15 hours in elderly patients, and from 2.5–30 hours in patients with liver cirrhosis. Approximately 2/3 of pindolol is metabolized in the liver giving hydroxylates, which are found in the urine as gluconurides and ethereal sulfates. The remaining 1/3 of pindolol is excreted in urine in unchanged form.

History

Pindolol was patented by Sandoz in 1966 and was launched in the US in 1977.[25]

Research

Depression

Pindolol has been investigated as an add-on drug to antidepressant therapy with SSRIs like fluoxetine in the treatment of depression since 1994.[5] The rationale behind this strategy has its basis in the fact that pindolol is an antagonist of the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor.[4] Presynaptic and somatodendritic 5-HT1A receptors act as inhibitory autoreceptors, inhibit serotonin release, and are pro-depressive in their action.[4] This is in contrast to postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors, which mediate antidepressant effects.[4] By blocking 5-HT1A autoreceptors at doses that are selective for them over postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors, pindolol may be able to disinhibit serotonin release and thereby improve the antidepressant effects of SSRIs.[4] The results of augmentation therapy with pindolol have been encouraging in early studies of low quality.[3] However, a 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials found no overall significant benefit.[5] There were also no significant differences in tolerability or safety.[5] Pindolol may be able to accelerate the onset of the antidepressant effects of SSRIs, however.[4]

Others

- Pindolol is a potent scavenger of nitric oxide. This effect is potentiated by sodium bicarbonate. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis has an anxiolytic effect in animals.[26]

- Augmentation therapy of premature ejaculation: According to a recent study, pindolol can be effectively added to a standard anti-premature-ejaculation therapy, which usually consists of daily doses of an SSRI antidepressant such as fluoxetine or paroxetine. Augmentation of pindolol results in substantial increase of ejaculatory latency, even in those who previously did not experience in an improvement with the SSRI monotherapy.[27]

See also

References

- Drugs.com International brand names for pindolol Archived 2017-10-01 at the Wayback Machine Page accessed Sept 4, 2015

- Wong, GW; Boyda, HN; Wright, JM (Nov 2014). "Blood pressure lowering efficacy of partial agonist beta blocker monotherapy for primary hypertension". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11 (11): CD007450. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007450.pub2. PMC 6486122. PMID 25427719.

- Blier P, Bergeron R (1998). "The use of pindolol to potentiate antidepressant medication". J Clin Psychiatry. 59 Suppl 5: 16–23, discussion 24–5. PMID 9635544.

- Celada P, Bortolozzi A, Artigas F (2013). "Serotonin 5-HT1A receptors as targets for agents to treat psychiatric disorders: rationale and current status of research". CNS Drugs. 27 (9): 703–16. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0071-0. PMID 23757185.

- Liu Y, Zhou X, Zhu D, Chen J, Qin B, Zhang Y, Wang X, Yang D, Meng H, Luo Q, Xie P (2015). "Is pindolol augmentation effective in depressed patients resistant to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors? A systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum Psychopharmacol. 30 (3): 132–42. doi:10.1002/hup.2465. PMID 25689398.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2010-08-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Hamon M, Lanfumey L, el Mestikawy S, Boni C, Miquel MC, Bolaños F, Schechter L, Gozlan H (1990). "The main features of central 5-HT1 receptors". Neuropsychopharmacology. 3 (5–6): 349–60. PMID 2078271.

- Weinshank RL, Zgombick JM, Macchi MJ, Branchek TA, Hartig PR (1992). "Human serotonin 1D receptor is encoded by a subfamily of two distinct genes: 5-HT1D alpha and 5-HT1D beta". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 (8): 3630–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.8.3630. PMC 48922. PMID 1565658.

- Krushinski JH, Schaus JM, Thompson DC, Calligaro DO, Nelson DL, Luecke SH, Wainscott DB, Wong DT (2007). "Indoloxypropanolamine analogues as 5-HT(1A) receptor antagonists". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17 (20): 5600–4. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.086. PMID 17804228.

- Boess FG, Martin IL (1994). "Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors". Neuropharmacology. 33 (3–4): 275–317. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(94)90059-0. PMID 7984267.

- Zgombick JM, Schechter LE, Macchi M, Hartig PR, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL (1992). "Human gene S31 encodes the pharmacologically defined serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine1E receptor". Mol. Pharmacol. 42 (2): 180–5. PMID 1513320.

- Adham N, Kao HT, Schecter LE, Bard J, Olsen M, Urquhart D, Durkin M, Hartig PR, Weinshank RL, Branchek TA (1993). "Cloning of another human serotonin receptor (5-HT1F): a fifth 5-HT1 receptor subtype coupled to the inhibition of adenylate cyclase". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 (2): 408–12. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.2.408. PMC 45671. PMID 8380639.

- Knight AR, Misra A, Quirk K, Benwell K, Revell D, Kennett G, Bickerdike M (2004). "Pharmacological characterisation of the agonist radioligand binding site of 5-HT(2A), 5-HT(2B) and 5-HT(2C) receptors". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 370 (2): 114–23. doi:10.1007/s00210-004-0951-4. PMID 15322733.

- Mos J, Van Hest A, Van Drimmelen M, Herremans AH, Olivier B (1997). "The putative 5-HT1A receptor antagonist DU125530 blocks the discriminative stimulus of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist flesinoxan in pigeons". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 325 (2–3): 145–53. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00131-3. PMID 9163561.

- Neijt HC, Karpf A, Schoeffter P, Engel G, Hoyer D (1988). "Characterisation of 5-HT3 recognition sites in membranes of NG 108-15 neuroblastoma-glioma cells with [3H]ICS 205-930". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 337 (5): 493–9. doi:10.1007/bf00182721. PMID 3412489.

- Hoyer D, Neijt HC (1988). "Identification of serotonin 5-HT3 recognition sites in membranes of N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells by radioligand binding". Mol. Pharmacol. 33 (3): 303–9. PMID 3352595.

- Wisden W, Parker EM, Mahle CD, Grisel DA, Nowak HP, Yocca FD, Felder CC, Seeburg PH, Voigt MM (1993). "Cloning and characterization of the rat 5-HT5B receptor. Evidence that the 5-HT5B receptor couples to a G protein in mammalian cell membranes". FEBS Lett. 333 (1–2): 25–31. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(93)80368-5. PMID 8224165.

- Plassat JL, Amlaiky N, Hen R (1993). "Molecular cloning of a mammalian serotonin receptor that activates adenylate cyclase". Mol. Pharmacol. 44 (2): 229–36. PMID 8394987.

- Bard JA, Zgombick J, Adham N, Vaysse P, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL (1993). "Cloning of a novel human serotonin receptor (5-HT7) positively linked to adenylate cyclase". J. Biol. Chem. 268 (31): 23422–6. PMID 8226867.

- Jasper JR, Kosaka A, To ZP, Chang DJ, Eglen RM (1997). "Cloning, expression and pharmacology of a truncated splice variant of the human 5-HT7 receptor (h5-HT7b)". Br. J. Pharmacol. 122 (1): 126–32. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0701336. PMC 1564895. PMID 9298538.

- Hoffmann C, Leitz MR, Oberdorf-Maass S, Lohse MJ, Klotz KN (2004). "Comparative pharmacology of human beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes--characterization of stably transfected receptors in CHO cells". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 369 (2): 151–9. doi:10.1007/s00210-003-0860-y. PMID 14730417.

- Luedtke RR, Freeman RA, Boundy VA, Martin MW, Huang Y, Mach RH (2000). "Characterization of (125)I-IABN, a novel azabicyclononane benzamide selective for D2-like dopamine receptors". Synapse. 38 (4): 438–49. doi:10.1002/1098-2396(20001215)38:4<438::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID 11044891.

- Artigas F, Adell A, Celada P (2006). "Pindolol augmentation of antidepressant response". Curr Drug Targets. 7 (2): 139–47. doi:10.2174/138945006775515446. PMID 16475955.

- "Discovery and Development of Major Drugs. Chapter 2 in Pharmaceutical Innovation: Revolutionizing Human Health. Volume 2 of Chemical Heritage Foundation series in innovation and entrepreneurship. Eds Ralph Landau, Basil Achilladelis, Alexander Scriabine. Chemical Heritage Foundation, 1999. ISBN 9780941901215 p 185

- Fernandes, E; Gomes, A; Costa, D; Lima, JL (2005). "Pindolol is a potent scavenger of reactive nitrogen species". Life Sciences. 77 (16): 1983–1992. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.02.018. PMID 15916777.

- Safarinejad, MR (2008). "Once-daily high-dose pindolol for paroxetine-refractory premature ejaculation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled and randomized study". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 28 (1): 39–44. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e31816073a5. PMID 18204339.