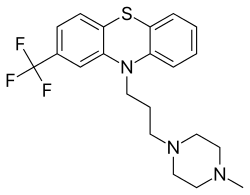

Trifluoperazine

Trifluoperazine, sold under a number of brand names, is a typical antipsychotic primarily used to treat schizophrenia.[1] It may also be used short term in those with generalized anxiety disorder but is less preferred to benzodiazepines.[1] It is of the phenothiazine chemical class.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Stelazine, Eskazinyl, Eskazine, Jatroneural, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682121 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, IM |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 10–20 hours |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.837 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H24F3N3S |

| Molar mass | 407.497 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Medical uses

Schizophrenia

Trifluoperazine is an effective antipsychotic for people with schizophrenia.[2] There is low-quality evidence that trifluoperazine increases the chance of being improved when compared to placebo when people are followed up for 19 weeks.[2] There is low-quality evidence that trifluoperazine reduces the risk of relapse when compared with placebo when people are followed for 5 months.[2] As of 2014 there was no good evidence for a difference between trifluoperazine and placebo with respect to the risk of experiencing intensified symptoms over a 16-week period nor in reducing significant agitation or distress.[2]

There is no good evidence that trifluoperazine is more effective for schizophrenia than lower-potency antipsychotics like chlorpromazine, chlorprothixene, thioridazine and levomepromazine, but trifluoperazine appears to cause more adverse effects than these drugs.[3]

Side effects

Its use in many parts of the world has declined because of highly frequent and severe early and late tardive dyskinesia, a type of extrapyramidal symptom. The annual development rate of tardive dyskinesia may be as high as 4%.

A 2004 meta-analysis of the studies on trifluoperazine found that it is more likely than placebo to cause extrapyramidal side effects such as akathisia, dystonia, and Parkinsonism.[6] It is also more likely to cause somnolence and anticholinergic side effects such as red eye and xerostomia (dry mouth).[6] All antipsychotics can cause the rare and sometimes fatal neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[7] Trifluoperazine can lower the seizure threshold.[8] The antimuscarinic action of trifluoperazine can cause excessive dilation of the pupils (mydriasis), which increases the chances of patients with hyperopia developing glaucoma.[9]

Contraindications

Trifluoperazine is contraindicated in CNS depression, coma, and blood dyscrasias. Trifluoperazine should be used with caution in patients suffering from renal or hepatic impairment.

Mechanism of action

Trifluoperazine has central antiadrenergic,[10] antidopaminergic,[11][12] and minimal anticholinergic effects.[13] It is believed to work by blockading dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in the mesocortical and mesolimbic pathways, relieving or minimizing such symptoms of schizophrenia as hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thought and speech.[6]

Names

Brand names include Eskazinyl, Eskazine, Jatroneural, Modalina, Stelazine, Terfluzine, Trifluoperaz, Triftazin.

In the United Kingdom and some other countries, trifluoperazine is sold and marketed under the brand 'Stelazine'.

The drug is sold as tablet, liquid and 'Trifluoperazine-injectable USP' for deep intramuscular short-term use. GP studying pharmacological data has indicated cases of neck vertebrae irreversible fusing leading to NHS preparations being predominantly of the liquid form trifluoperazine as opposed to the tablet form as in Stela zine etc.

In the past, trifluoperazine was used in fixed combinations with the MAO inhibitor (antidepressant) tranylcypromine (tranylcypromine/trifluoperazine) to attenuate the strong stimulating effects of this antidepressant. This combination was sold under the brand name Jatrosom N. Likewise a combination with amobarbital (potent sedative/hypnotic agent) for the amelioration of psychoneurosis and insomnia existed under the brand name Jalonac. In Italy the first combination is still available, sold under the brand name Parmodalin (10 mg of tranylcypromine and 1 mg of trifluoperazine).

References

- "Trifluoperazine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Koch, K; Mansi, K; Haynes, E (2014). "Trifluoperazine versus placebo for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD010226.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010226.pub2. PMC 6718209. PMID 24414883. Lay summary (20 July 2017).

- Tardy, M; Dold, M; Engel, RR; Leucht, S (8 July 2014). "Trifluoperazine versus low-potency first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD009396. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009396.pub2. PMID 25003310.

- David S. Baldwin, Polkinghorn (2005). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of generalized anxiety disorder". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 8 (2): 293–302. doi:10.1017/S1461145704004870. PMID 15576000.

- Deetz, T. R.; Sawyer, M. H.; Billman, G.; Schuster, F. L.; Visvesvara, G. S. (2003). "Successful Treatment of Balamuthia Amoebic Encephalitis: Presentation of 2 Cases". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 37 (10): 1304–1312. doi:10.1086/379020. ISSN 1058-4838.

- Marques LO, Lima MS, Soares BG (2004). "Trifluoperazine for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003545. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003545.pub2. PMID 14974020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Smego RA, Durack DT (June 1982). "The neuroleptic malignant syndrome". Archives of Internal Medicine. 142 (6): 1183–5. doi:10.1001/archinte.142.6.1183. PMID 6124221.

- Hedges D, Jeppson K, Whitehead P (July 2003). "Antipsychotic medication and seizures: a review". Drugs of Today (Barcelona, Spain : 1998). 39 (7): 551–7. doi:10.1358/dot.2003.39.7.799445. PMID 12973403.

- Boet DJ (July 1970). "Toxic effects of phenothiazines on the eye". Documenta Ophthalmologica. Advances in Ophthalmology. 28 (1): 1–69. doi:10.1007/BF00153873. PMID 5312274.

- Huerta-Bahena J, Villalobos-Molina R, García-Sáinz JA (January 1983). "Trifluoperazine and chlorpromazine antagonize alpha 1- but not alpha2- adrenergic effects". Molecular Pharmacology. 23 (1): 67–70. PMID 6135146. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- Seeman P, Lee T, Chau-Wong M, Wong K (June 1976). "Antipsychotic drug doses and neuroleptic/dopamine receptors". Nature. 261 (5562): 717–9. Bibcode:1976Natur.261..717S. doi:10.1038/261717a0. PMID 945467.

- Creese I, Burt DR, Snyder SH (1996). "Dopamine receptor binding predicts clinical and pharmacological potencies of antischizophrenic drugs". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 8 (2): 223–6. doi:10.1176/jnp.8.2.223. PMID 9081563. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- Ebadi, Manuchair S (1998). "Trifluoperazine Hydrochloride". CRC desk reference of clinical pharmacology (illustrated ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-9683-0. Retrieved 2009-06-21.