Imipramine

Imipramine, sold under the brand name Tofranil among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) which is used mainly in the treatment of depression. It is also effective in treating anxiety and panic disorder. The drug is also used to treat bedwetting. It is taken by mouth. A long-acting form for injection into muscle is also available.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tofranil, Tofranil-PM, others |

| Other names | Melipramine; G-22355 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682389 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 94–96%[1] |

| Protein binding | 86%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2D6)[2] |

| Metabolites | Desipramine[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 20 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Renal (80%), fecal (20%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.039 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H24N2 |

| Molar mass | 280.407 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects of imipramine include dry mouth, drowsiness, dizziness, low blood pressure, rapid heart rate, urinary retention, and electrocardiogram changes. Overdose can result in death. The drug appears to work by increasing levels of serotonin and norepinephrine and by blocking certain serotonin, adrenergic, histamine, and cholinergic receptors.

Imipramine was discovered in 1951 and was introduced for medical use in 1957. It was the first TCA to be marketed. Imipramine and the other TCAs have decreased in use in recent decades due to the introduction of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which have fewer side effects and are safer in overdose.

Medical uses

Imipramine is used in the treatment of depression and certain anxiety disorders. It is similar in efficacy to the antidepressant drug moclobemide.[3] It has also been used to treat nocturnal enuresis because of its ability to shorten the time of delta wave stage sleep, where wetting occurs. In veterinary medicine, imipramine is used with xylazine to induce pharmacologic ejaculation in stallions. Blood levels between 150-250 ng/mL of imipramine plus its metabolite desipramine generally correspond to antidepressant efficacy.[4]

Available forms

Imipramine is available in the form of oral tablets and as a formulation for depot intramuscular injection.

Contraindications

Combining it with alcohol consumption causes excessive drowsiness. It may be unsafe during pregnancy.

Side effects

Those listed in italics below denote common side effects.[5]

- Central nervous system: dizziness, drowsiness, confusion, seizures, headache, anxiety, tremors, stimulation, weakness, insomnia, nightmares, extrapyramidal symptoms in geriatric patients, increased psychiatric symptoms, paresthesia

- Cardiovascular: orthostatic hypotension, ECG changes, tachycardia, hypertension, palpitations, dysrhythmias

- Eyes, ears, nose and throat: blurred vision, tinnitus, mydriasis

- Gastrointestinal: dry mouth, nausea, vomiting, paralytic ileus, increased appetite, cramps, epigastric distress, jaundice, hepatitis, stomatitis, constipation, taste change

- Genitourinary: urinary retention

- Hematological: agranulocytosis, thrombocytopenia, eosinophilia, leukopenia

- Skin: rash, urticaria, diaphoresis, pruritus, photosensitivity

Overdose

Interactions

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | IMI | DSI | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 1.3–1.4 | 17.6–163 | Human | [7][8] |

| NET | 20–37 | 0.63–3.5 | Human | [7][8] |

| DAT | 8,500 | 3,190 | Human | [7] |

| 5-HT1A | ≥5,800 | ≥6,400 | Human | [9][10][11] |

| 5-HT2A | 80–150 | 115–350 | Human | [9][11] |

| 5-HT2C | 120 | 244–748 | Human/rat | [12][13][10] |

| 5-HT3 | 970–3,651 | ≥2,500 | Rodent | [10][14] |

| 5-HT6 | 190–209 | ND | Rat | [15] |

| 5-HT7 | >1,000 | >1,000 | Rat | [16] |

| α1 | 32 | 23–130 | Human | [9][17][8] |

| α2 | 3,100 | ≥1,379 | Human | [9][17][8] |

| β | >10,000 | ≥1,700 | Rat | [18][19][20] |

| D1 | >10,000 | 5,460 | Human | [10][21] |

| D2 | 620–726 | 3,400 | Human | [21][10][17] |

| D3 | 387 | ND | Human | [10] |

| H1 | 7.6–37 | 60–110 | Human | [9][17][22] |

| H2 | 550 | 1,550 | Human | [22] |

| H3 | >100,000 | >100,000 | Human | [22] |

| H4 | 24,000 | 9,550 | Human | [22] |

| mACh | 46 | 66–198 | Human | [9][17] |

| M1 | 42 | 110 | Human | [23] |

| M2 | 88 | 540 | Human | [23] |

| M3 | 60 | 210 | Human | [23] |

| M4 | 112 | 160 | Human | [23] |

| M5 | 83 | 143 | Human | [23] |

| α3β4 | 410–970 | ND | Human | [24] |

| σ1 | 332–520 | 1,990–4,000 | Rodent | [25][26][27] |

| σ2 | 327–2,100 | ≥1,611 | Rat | [6][26][27] |

| hERG | 3,400 | ND | Human | [28] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | ||||

Imipramine affects numerous neurotransmitter systems known to be involved in the etiology of depression, anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), enuresis and numerous other mental and physical conditions. Imipramine is similar in structure to some muscle relaxants, and has a significant analgesic effect and, thus, is very useful in some pain conditions.

The mechanisms of imipramine's actions include, but are not limited to, effects on:

- Serotonin: very strong reuptake inhibition.

- Norepinephrine: strong reuptake inhibition. Desipramine has more affinity to norepinephrine transporter than imipramine.

- Dopamine: imipramine blocks D2 receptors.[29] Imipramine, and its metabolite desipramine, have no appreciable affinity for the dopamine transporter (Ki = 8,500 and >10,000 nM, respectively).[30]

- Acetylcholine: imipramine is an anticholinergic, specifically an antagonist of the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Thus, it is prescribed with caution to the elderly and with extreme caution to those with psychosis, as the general brain activity enhancement in combination with the "dementing" effects of anticholinergics increases the potential of imipramine to cause hallucinations, confusion and delirium in this population.

- Epinephrine: imipramine antagonizes adrenergic receptors, thus sometimes causing orthostatic hypotension.

- Sigma receptor: activity on sigma receptors is present, but it is very weak (Ki = 520 nM) and it is about half that of amitriptyline (Ki = 300 nM).

- Histamine: imipramine is an antagonist of the histamine H1 receptors.

- BDNF: BDNF is implicated in neurogenesis in the hippocampus, and studies suggest that depressed patients have decreased levels of BDNF and reduced hippocampal neurogenesis. It is not clear how neurogenesis restores mood, as ablation of hippocampal neurogenesis in murine models do not show anxiety related or depression related behaviours. Chronic imipramine administration results in increased histone acetylation (which is associated with transcriptional activation and decondensed chromatin) at the hippocampal BDNF promoter, and also reduced expression of hippocampal HDAC5.[31][32]

Pharmacokinetics

Within the body, imipramine is converted into desipramine (desmethylimipramine) as a metabolite.

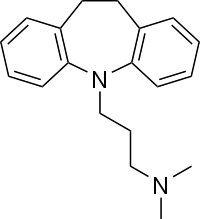

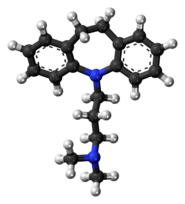

Chemistry

Imipramine is a tricyclic compound, specifically a dibenzazepine, and possesses three rings fused together with a side chain attached in its chemical structure.[33] Other dibenzazepine TCAs include desipramine (N-desmethylimipramine), clomipramine (3-chloroimipramine), trimipramine (2'-methylimipramine or β-methylimipramine), and lofepramine (N-(4-chlorobenzoylmethyl)desipramine).[33][34] Imipramine is a tertiary amine TCA, with its side chain-demethylated metabolite desipramine being a secondary amine.[35][36] Other tertiary amine TCAs include amitriptyline, clomipramine, dosulepin (dothiepin), doxepin, and trimipramine.[37][38] The chemical name of imipramine is 3-(10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,f]azepin-5-yl)-N,N-dimethylpropan-1-amine and its free base form has a chemical formula of C19H24N2 with a molecular weight of 280.407 g/mol.[39] The drug is used commercially mostly as the hydrochloride salt; the embonate (pamoate) salt is used for intramuscular administration and the free base form is not used.[39][40] The CAS Registry Number of the free base is 50-49-7, of the hydrochloride is 113-52-0, and of the embonate is 10075-24-8.[39][40]

History

The parent compound of imipramine, 10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenz[b,f]azepine (dibenzazepine), was first synthesized in 1899, but no pharmacological assessment of this compound or any substituted derivatives was undertaken until the late 1940s.[41][42][43] Imipramine was first synthesized in 1951, as an antihistamine.[44][45] The antipsychotic effects of chlorpromazine were discovered in 1952,[46] and imipramine was then developed and studied as an antipsychotic for use in patients with schizophrenia.[17][47] The medication was tested in several hundred patients with psychosis, but showed little effectiveness.[48] However, imipramine was serendipitously found to possess antidepressant effects in the mid-1950s following a case report of symptom improvement in a woman with severe depression who had been treated with it.[17][47][49] This was followed by similar observations in other patients and further clinical research.[50][48] Subsequently, imipramine was introduced for the treatment of depression in Europe in 1958 and in the United States in 1959.[51] Along with the discovery and introduction of the monoamine oxidase inhibitor iproniazid as an antidepressant around the same time, imipramine resulted in the establishment of monoaminergic drugs as antidepressants.[49][50][48]

In the late 1950s, imipramine was the first TCA to be developed (by Ciba). At the first international congress of neuropharmacology in Rome, September 1958 Dr Freyhan from the University of Pennsylvania discussed as one of the first clinicians the effects of imipramine in a group of 46 patients, most of them diagnosed as "depressive psychosis". The patients were selected for this study based on symptoms such as depressive apathy, kinetic retardation and feelings of hopelessness and despair. In 30% of all patients, he reported optimal results, and in around 20%, failure. The side effects noted were atropine-like, and most patients suffered from dizziness. Imipramine was first tried against psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, but proved ineffective. As an antidepressant, it did well in clinical studies and it is known to work well in even the most severe cases of depression.[52] It is not surprising, therefore, that imipramine may cause a high rate of manic and hypomanic reactions in hospitalized patients with pre-existing bipolar disorder, with one study showing that up to 25% of such patients maintained on Imipramine switched into mania or hypomania.[53] Such powerful antidepressant properties have made it favorable in the treatment of treatment-resistant depression.

Before the advent of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), its sometimes intolerable side-effect profile was considered more tolerable. Therefore, it became extensively used as a standard antidepressant and later served as a prototypical drug for the development of the later-released TCAs. Today it is no longer used as commonly, but is sometimes still prescribed as a second-line treatment for treating major depression . It has also seen limited use in the treatment of migraines, ADHD, and post-concussive syndrome. Imipramine has additional indications for the treatment of panic attacks, chronic pain, and Kleine-Levin syndrome. In pediatric patients, it is relatively frequently used to treat pavor nocturnus and nocturnal enuresis.

Society and culture

Generic names

Imipramine is the English and French generic name of the drug and its INN, BAN, and DCF, while imipramine hydrochloride is its USAN, USP, BANM, and JAN.[39][40][54][55] Its generic name in Spanish and Italian and its DCIT are imipramina, in German is imipramin, and in Latin is imipraminum.[40][55] The embonate salt is known as imipramine pamoate.[40][55]

Brand names

Imipramine is marketed throughout the world mainly under the brand name Tofranil.[40][55] Imipramine pamoate is marketed under the brand name Tofranil-PM for intramuscular injection.[40][55][56]

Availability

Imipramine is available for medical use widely throughout the world, including in the United States, the United Kingdom, elsewhere in Europe, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.[55]

References

- Heck HA, Buttrill SE Jr, Flynn NW, Dyer RL, Anbar M, Cairns T, Dighe S, Cabana BE (June 1979). "Bioavailability of imipramine tablets relative to a stable isotope-labelled internal standard: increasing the power of bioavailability tests". Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics. 7 (3): 233–248. doi:10.1007/bf01060015. PMID 480146.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "PRODUCT INFORMATION TOLERADE® (imipramine hydrochloride)". TGA eBusiness Services. PMIP Pty Ltd. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- Delini-Stula, A; Mikkelsen, H; Angst, J (October 1995). "Therapeutic efficacy of antidepressants in agitated anxious depression--a meta-analysis of moclobemide studies". Journal of Affective Disorders. 35 (1–2): 21–30. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(95)00034-K. PMID 8557884.

- Orsulak, PJ (September 1989). "Therapeutic monitoring of antidepressant drugs: guidelines updated". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 11 (5): 497–507. doi:10.1097/00007691-198909000-00002. PMID 2683251.

- Skidmore-Roth, L., ed. (2010). Mosby's Nursing Drug Reference (23rd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

- Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB (1997). "Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolites". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 283 (3): 1305–22. PMID 9400006.

- Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology. 114 (4): 559–65. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217.

- Toll L, Berzetei-Gurske IP, Polgar WE, Brandt SR, Adapa ID, Rodriguez L, Schwartz RW, Haggart D, O'Brien A, White A, Kennedy JM, Craymer K, Farrington L, Auh JS (1998). "Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications". NIDA Res. Monogr. 178: 440–66. PMID 9686407.

- Wander TJ, Nelson A, Okazaki H, Richelson E (1986). "Antagonism by antidepressants of serotonin S1 and S2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 132 (2–3): 115–21. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90596-0. PMID 3816971.

- Roth BL, Kroeze WK (2006). "Screening the receptorome yields validated molecular targets for drug discovery". Curr. Pharm. Des. 12 (14): 1785–95. doi:10.2174/138161206776873680. PMID 16712488.

- Pälvimäki EP, Roth BL, Majasuo H, Laakso A, Kuoppamäki M, Syvälahti E, Hietala J (1996). "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor". Psychopharmacology. 126 (3): 234–40. doi:10.1007/bf02246453. PMID 8876023.

- Schmidt AW, Hurt SD, Peroutka SJ (1989). "'[3H]quipazine' degradation products label 5-HT uptake sites". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 171 (1): 141–3. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90439-1. PMID 2533080.

- Monsma FJ, Shen Y, Ward RP, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR (1993). "Cloning and expression of a novel serotonin receptor with high affinity for tricyclic psychotropic drugs". Mol. Pharmacol. 43 (3): 320–7. PMID 7680751.

- Shen Y, Monsma FJ, Metcalf MA, Jose PA, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR (1993). "Molecular cloning and expression of a 5-hydroxytryptamine7 serotonin receptor subtype". J. Biol. Chem. 268 (24): 18200–4. PMID 8394362.

- Richelson E, Nelson A (1984). "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 230 (1): 94–102. PMID 6086881.

- Andersen PH (1989). "The dopamine inhibitor GBR 12909: selectivity and molecular mechanism of action". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 166 (3): 493–504. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90363-4. PMID 2530094.

- Muth EA, Haskins JT, Moyer JA, Husbands GE, Nielsen ST, Sigg EB (1986). "Antidepressant biochemical profile of the novel bicyclic compound Wy-45,030, an ethyl cyclohexanol derivative". Biochem. Pharmacol. 35 (24): 4493–7. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(86)90769-0. PMID 3790168.

- Sánchez C, Hyttel J (1999). "Comparison of the effects of antidepressants and their metabolites on reuptake of biogenic amines and on receptor binding". Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 19 (4): 467–89. doi:10.1023/A:1006986824213. PMID 10379421.

- Deupree JD, Montgomery MD, Bylund DB (2007). "Pharmacological properties of the active metabolites of the antidepressants desipramine and citalopram". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 576 (1–3): 55–60. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.08.017. PMC 2231336. PMID 17850785.

- Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H₁R, H₂R, H₃R, and H₄R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 385 (2): 145–70. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803.

- Stanton T, Bolden-Watson C, Cusack B, Richelson E (1993). "Antagonism of the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in CHO-K1 cells by antidepressants and antihistaminics". Biochem. Pharmacol. 45 (11): 2352–4. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90211-e. PMID 8100134.

- Arias HR, Targowska-Duda KM, Feuerbach D, Sullivan CJ, Maciejewski R, Jozwiak K (2010). "Different interaction between tricyclic antidepressants and mecamylamine with the human alpha3beta4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel". Neurochem. Int. 56 (4): 642–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2010.01.011. PMID 20117161.

- Weber E, Sonders M, Quarum M, McLean S, Pou S, Keana JF (1986). "1,3-Di(2-[5-3H]tolyl)guanidine: a selective ligand that labels sigma-type receptors for psychotomimetic opiates and antipsychotic drugs". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83 (22): 8784–8. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.8784W. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.22.8784. PMC 387016. PMID 2877462.

- Hindmarch I, Hashimoto K (2010). "Cognition and depression: the effects of fluvoxamine, a sigma-1 receptor agonist, reconsidered". Hum Psychopharmacol. 25 (3): 193–200. doi:10.1002/hup.1106. PMID 20373470.

- Robson MJ, Elliott M, Seminerio MJ, Matsumoto RR (2012). "Evaluation of sigma (σ) receptors in the antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in vitro and in vivo". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 22 (4): 308–17. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.08.002. PMID 21911285.

- Teschemacher AG, Seward EP, Hancox JC, Witchel HJ (1999). "Inhibition of the current of heterologously expressed HERG potassium channels by imipramine and amitriptyline". Br. J. Pharmacol. 128 (2): 479–85. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0702800. PMC 1571643. PMID 10510461.

- Smiałowski, A. (1991-05-01). "Dopamine D2 receptor blocking effect of imipramine in the rat hippocampus". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 39 (1): 105–108. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(91)90404-p. ISSN 0091-3057. PMID 1924491.

- Schulze, David R.; Carroll, F. Ivy; McMahon, Lance R. (2012-08-01). "Interactions between dopamine transporter and cannabinoid receptor ligands in rhesus monkeys". Psychopharmacology. 222 (3): 425–438. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2661-9. ISSN 0033-3158. PMC 3620032. PMID 22374253.

- Tsankova, N. M.; Berton, O; Renthal, W; Kumar, A; Neve, R. L.; Nestler, E. J. (April 2006). "Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action". Nature Neuroscience. 9 (4): 519–25. doi:10.1038/nn1659. PMID 16501568.

- Krishnan, V; Nestler, E. J. (October 2008). "The molecular neurobiology of depression". Nature. 455 (7215): 894–902. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..894K. doi:10.1038/nature07455. PMC 2721780. PMID 18923511.

- Michael S Ritsner (15 February 2013). Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I: Multiple Medication Use Strategies. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-94-007-5805-6.

- Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 580–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- Neal R. Cutler; John J. Sramek; Prem K. Narang (20 September 1994). Pharmacodynamics and Drug Development: Perspectives in Clinical Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-471-95052-3.

- Pavel Anzenbacher; Ulrich M. Zanger (23 February 2012). Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-3-527-64632-6.

- Patricia K. Anthony (2002). Pharmacology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 39–. ISBN 1-56053-470-2.

- Philip Cowen; Paul Harrison; Tom Burns (9 August 2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. OUP Oxford. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-0-19-162675-3.

- J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 680–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 546–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- Boschmans SA, Perkin MF, Terblanche SE (1987). "Antidepressant drugs: imipramine, mianserin and trazodone". Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C, Comp. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 86 (2): 225–32. doi:10.1016/0742-8413(87)90073-9. PMID 2882911.

- Ban TA (May 2001). "Pharmacotherapy of mental illness--a historical analysis". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 25 (4): 709–27. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(01)00160-9. PMID 11383974.

- Jørgensen, Tine Krogh; Andersen, Knud Erik; Lau, Jesper; Madsen, Peter; Huusfeldt, Per Olaf (1999). "Synthesis of substituted 10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenz[b,f]azepines; key synthons in syntheses of pharmaceutically active compounds". Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 36 (1): 57–64. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570360110. ISSN 0022-152X.

- Walker, S. R. (2012). Trends and Changes in Drug Research and Development. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109. ISBN 9789400926592.

- Takehiko Watanabe; Hiroshi Wada (22 February 1991). Histaminergic Neurons. CRC Press. pp. 272–. ISBN 978-0-8493-6425-9.

- Max R. Bennett (21 April 2014). History of the Synapse. CRC Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-4822-8417-1.

- E. Siobhan Mitchell; D. J. Triggle (2009). Antidepressants. Infobase Publishing. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-1-4381-0192-7.

- Yong-Ku Kim (2 January 2018). Understanding Depression: Volume 2. Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis and Treatment. Springer. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-981-10-6577-4.

- Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, Krystal JH (May 2018). "The neurobiology of depression, ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: Is it glutamate inhibition or activation?". Pharmacol. Ther. 190: 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.05.010. PMC 6165688. PMID 29803629.

- George Stein; Greg Wilkinson (April 2007). Seminars in General Adult Psychiatry. RCPsych Publications. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-904671-44-2.

- W. Lowry (6 December 2012). Forensic Toxicology: Controlled Substances and Dangerous Drugs. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 248–. ISBN 978-1-4684-3444-6.

- Healy, David (1997). The Antidepressant Era. Harvard University Press. p. 211.

- Bottlender, R; Rudolf, D; Strauss, A; Möller, H. J. (1998). "Antidepressant-associated maniform states in acute treatment of patients with bipolar-I depression". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 248 (6): 296–300. doi:10.1007/s004060050053. PMID 9928908.

- I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 151–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- https://www.drugs.com/international/imipramine.html

- Ronald W. Pies (2 April 2007). Handbook of Essential Psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-1-58562-660-1.

External links

- Imipramine – Medicinenet.com

- Neurotransmitter – Neurotransmitter.net

- Imipramine bound to proteins in the PDB

- U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information: Medical Genetics Summaries - Imipramine Therapy and CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotype