Carvedilol

Carvedilol, sold under the brand name Coreg among others, is a medication used to treat high blood pressure, congestive heart failure (CHF), and left ventricular dysfunction in people who are otherwise stable.[1] For high blood pressure, it is generally a second-line treatment.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Coreg, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697042 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 25–35% |

| Protein binding | 98% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6, CYP2C9) |

| Elimination half-life | 7–10 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (16%), Feces (60%) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.117.236 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

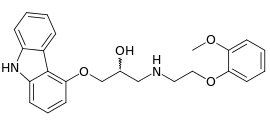

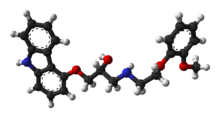

| Formula | C24H26N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 406.474 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include dizziness, tiredness, joint pain, low blood pressure, nausea, and shortness of breath.[1] Severe side effects may include bronchospasm.[1] Safety during pregnancy or breastfeeding is unclear.[2] Use is not recommended with liver problems.[3] Carvedilol is a nonselective beta blocker and alpha-1 blocker.[1] How it improves outcomes is not entirely clear but may involve dilation of blood vessels.[1]

Carvedilol was patented in 1978 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1995.[1][4] It is available as a generic medication.[1] In the United States, the wholesale cost per dose is less than 0.05 USD as of 2018.[5] In 2016, it was the 30th most prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 23 million prescriptions.[6]

Medical use

Carvedilol is indicated in the management of congestive heart failure (CHF), commonly as an adjunct to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (ACE inhibitors) and diuretics. It has been clinically shown to reduce mortality and hospitalizations in people with CHF.[7] The mechanism behind its positive effect when used long-term in clinically stable CHF patients is not fully understood, but is thought to contribute to remodeling of the heart, improving upon its structure and function.[8][9]

In addition, carvedilol is indicated in the treatment of hypertension and to reduce risk of mortality and hospitalizations in a subset of people following a heart attack.[10] It can be used alone or with other anti-hypertensive agents.

Contraindications

According to the FDA, carvedilol should not be used in people with bronchial asthma or bronchospastic conditions. It should not be used in people with second- or third-degree AV block, sick sinus syndrome, severe bradycardia (unless a permanent pacemaker is in place), or a decompensated heart condition. People with severe hepatic impairment are also advised to not take carvedilol.[11]

Side effects

The most common side effects (>10% incidence) include:[12]

- dizziness

- fatigue

- low blood pressure

- diarrhea

- weakness

- slowed heart rate

- weight gain

- erectile dysfunction

Carvedilol is not recommended for people with uncontrolled bronchospastic disease (e.g. current asthma symptoms) as it can block receptors that assist in opening the airways.[12]

Carvedilol may mask symptoms of low blood sugar (hypoglycemia),[12] resulting in hypoglycemia unawareness. This is termed beta blocker induced hypoglycemia unawareness.

Mechanism of action

Carvedilol is both a non-selective beta adrenergic receptor blocker (β1, β2) and an alpha adrenergic receptor blocker (α1). The S(-) enantiomer accounts for the beta blocking activity whereas the S(-) and R(+) enantiomer have alpha blocking activity.[12]

Carvedilol reversibly binds to beta adrenergic receptors on cardiac myocytes. Inhibition of these receptors prevents a response to the sympathetic nervous system, leading to decreased heart rate and contractility. This action is beneficial in heart failure patients where the sympathetic nervous system is activated as a compensatory mechanism.[13]

Carvedilol blockade of α1 receptors causes vasodilation of blood vessels. This inhibition leads to decreased peripheral vascular resistance and an antihypertensive effect. There is no reflex tachycardia response due to carvedilol blockade of β1 receptors on the heart.[14]

Pharmacokinetics

Carvedilol is about 25% to 35% bioavailable following oral administration due to extensive first-pass metabolism. The compound is metabolized by liver enzymes, CYP2D6 and CYP2C9 via aromatic ring oxidation and glucuronidation, then further conjugated by glucuronidation and sulfation. The three active metabolites exhibit only one tenth of the vasodilating effect of the parent compound. However, the 4’hydroxyphenyl metabolite is about 13-fold more potent in β-blockade than the parent.[12]

The mean half-life of carvedilol following oral administration ranges from 7 to 10 hours. The pharmaceutical product is a mix of two enantiomorphs, R(+)-carvedilol and S(-)-carvedilol, with differing metabolic properties. R(+)-carvedilol undergoes preferential selection for metabolism, which results in a fractional half-life of about 5 to 9 hours, compared with 7 to 11 hours for the S(-)-carvedilol fraction.[12]

The majority of carvedilol is bound to plasma proteins (98%), mainly to albumin. Carvedilol is a basic, hydrophobic compound with a steady-state volume of distribution of 115 L. Plasma clearance ranges from 500 to 700 mL/min.[12]

Absorption is slowed when administered with food, however, it does not show a significant difference in bioavailability. Taking carvedilol with food decreases the risk of orthostatic hypotension.[12]

Formulations

• Tablet, Oral [12]

• Capsule Extended Release 24 Hour, Oral[15]

In 2006, the FDA approved an extended-release formulation.[15]

References

- "Carvedilol Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Carvedilol Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 147. ISBN 9780857113382.

- Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 463. ISBN 9783527607495.

- "NADAC as of 2018-12-19". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "The Top 300 of 2019". clincalc.com. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "2013 AHA Guidelines for the Management of Heart Failure" (PDF).

- Biaggioni, MD, Italo (2009). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology 11th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. p. 189. ISBN 9780071604055.

- Reis Filho JR, Cardoso JN, Cardoso CM, Pereira-Barretto AC (June 2015). "Reverse Cardiac Remodeling: A Marker of Better Prognosis in Heart Failure". Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 104 (6): 502–6. doi:10.5935/abc.20150025. PMC 4484683. PMID 26131706.

- Sackner-Bernstein JD (May 2004). "Practical guidelines to optimize effectiveness of beta-blockade in patients postinfarction and in those with chronic heart failure". The American Journal of Cardiology. 93 (9A): 69B–73B. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.029. PMID 15144942.

- "Carvedilol Package Insert" (PDF). GlaxoSmithKline.

- "Coreg - Food and Drug Administration" (PDF).

- Manurung D, Trisnohadi HB (2007). "Beta blockers for congestive heart failure" (PDF). Acta Medica Indonesiana. 39 (1): 44–8. PMID 17297209.

- Ruffolo RR, Gellai M, Hieble JP, Willette RN, Nichols AJ (1990). "The pharmacology of carvedilol". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 38 Suppl 2: S82–8. doi:10.1007/BF01409471. PMID 1974511.

- "Drug Approval Package". www.accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-05.

Further reading

- Chakraborty S, Shukla D, Mishra B, Singh S (February 2010). "Clinical updates on carvedilol: a first choice beta-blocker in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 6 (2): 237–50. doi:10.1517/17425250903540220. PMID 20073998.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carvedilol. |

- Physicians Desk Reference Info on Carvedilol

- Info on carvedilol through rxlist.com

- U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information: Medical Genetics Summaries - Carvedilol Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype