Dobutamine

Dobutamine is a medication used in the treatment of cardiogenic shock and severe heart failure.[1][2] It may also be used in certain types of cardiac stress tests.[1] It is given by injection into a vein or intraosseous as a continuous infusion.[1] The amount of medication needs to be adjusted to the desired effect.[1] Onset of effects is generally seen within 2 minutes.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dobutrex, Inotrex, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682861 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous, intraosseous[1] |

| Drug class | β1-agonist |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Onset of action | Within 2 min[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 2 minutes |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

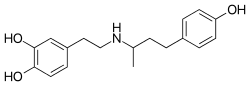

| Formula | C18H23NO3 |

| Molar mass | 301.38 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include a fast heart rate, an irregular heart beat, and inflammation at the site of injection.[1][3] Use is not recommended in those with idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis.[1] It primarily works by direct stimulation of β1 receptors, which increases the strength of the heart's contractions.[1] Generally it has little effect on a person's heart rate.[1]

Dobutamine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1978.[1] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In the United Kingdom as of 2018 it costs the NHS about 2 pounds per vial.[3] It was initially made from isoproterenol.[2]

Medical uses

Dobutamine is used to treat acute but potentially reversible heart failure, such as which occurs during cardiac surgery or in cases of septic or cardiogenic shock, on the basis of its positive inotropic action.[4]

Dobutamine can be used in cases of congestive heart failure to increase cardiac output. It is indicated when parenteral therapy is necessary for inotropic support in the short-term treatment of patients with cardiac decompensation due to depressed contractility, which could be the result of either organic heart disease or cardiac surgical procedures. It is not useful in ischemic heart disease because it increases heart rate and thus increases myocardial oxygen demand.

The drug is also commonly used in the hospital setting as a pharmacologic stress testing agent to identify coronary artery disease.

Adverse effects

Primary side effects include those commonly seen for β1 active sympathomimetics, such as hypertension, angina, arrhythmia, and tachycardia. Used with caution in atrial fibrillation as it has the effect of increasing the atrioventricular (AV) conduction.[5]

The most dangerous side effect of dobutamine is increased risk of arrhythmia, including fatal arrhythmias.

Pharmacology

Dobutamine is a direct-acting agent whose primary activity results from stimulation of the β1-adrenoceptors of the heart, increasing contractility and cardiac output. Since it does not act on dopamine receptors to inhibit the release of norepinephrine (another α1 agonist), dobutamine is less prone to induce hypertension than is dopamine.

Dobutamine is predominantly a β1-adrenergic agonist, with weak β2 activity, and α1 selective activity, although it is used clinically in cases of cardiogenic shock for its β1 inotropic effect in increasing heart contractility and cardiac output. Dobutamine is administered as a racemic mixture consisting of both (+) and (−) isomers; the (+) isomer is a potent β1 agonist and α1 antagonist, while the (−) isomer is an α1 agonist.[6] The administration of the racemate results in the overall β1 agonism responsible for its activity. (+)-Dobutamine also has mild β2 agonist activity, which makes it useful as a vasodilator.[7]

History

It was developed in the 1970s by Drs. Ronald Tuttle and Jack Mills at Eli Lilly and Company, as a structural analogue of isoprenaline.[8]

References

- "Dobutamine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- Wilson, William C.; Grande, Christopher M.; Hoyt, David B. (2007). Trauma: Critical Care. CRC Press. p. 302. ISBN 9781420016840.

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 220–221. ISBN 9780857113382.

- Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM, Flower RJ. Rang and Dale's Pharmacology.

- Shen, Howard (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 6. ISBN 1-59541-101-1.

- Parker K, Brunton L, Goodman LS, Blumenthal D, Buxton I (2008). Goodman & Gilman's manual of pharmacology and therapeutics. McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 159. ISBN 0-07-144343-6.

- Tibayan FA, Chesnutt AN, Folkesson HG, Eandi J, Matthay MA (1997). "Dobutamine increases alveolar liquid clearance in ventilated rats by beta-2 receptor stimulation". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156 (2 Pt 1): 438–44. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9609141. PMID 9279221.

- Tuttle RR, Mills J (January 1975). "Dobutamine: development of a new catecholamine to selectively increase cardiac contractility". Circ Res. 36 (1): 185–96. doi:10.1161/01.RES.36.1.185. PMID 234805.