Asenapine

Asenapine, sold under the trade names Saphris and Sycrest among others, is an atypical antipsychotic medication used to treat schizophrenia and acute mania associated with bipolar disorder.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Saphris, Sycrest |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a610015 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | sublingual |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 35% (sublingual), <2% (Oral)[1][2][3][4] |

| Protein binding | 95%[1][2][3][4] |

| Metabolism | hepatic (glucurinodation by UGT1A4 and oxidative metabolism by CYP1A2)[1][2][3][4] |

| Elimination half-life | 24 hours[1][2][3][4] |

| Excretion | Renal (50%), Faecal (40%; ~5-16% as unchanged drug in faeces)[1][2][3][4] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.059.828 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

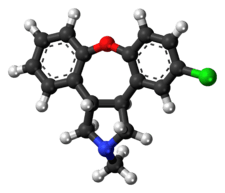

| Formula | C17H16ClNO |

| Molar mass | 285.77 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

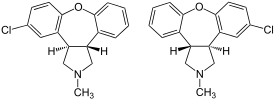

It was chemically derived via altering the chemical structure of the tetracyclic (atypical) antidepressant, mianserin.[5]

Medical uses

Asenapine has been approved by the FDA for the acute treatment of adults with schizophrenia and acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder with or without psychotic features in adults.[6] In Australia asenapine's approved (and also listed on the PBS) indications include the following:[7]

- Schizophrenia

- Treatment, for up to 6 months, of an episode of acute mania or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder

- Maintenance treatment, as monotherapy, of bipolar I disorder

In the European Union and the UK asenapine is only licensed for use as a treatment for acute mania in bipolar I disorder.[3][4]

Absorbed readily if administered sublingually, asenapine is poorly absorbed when swallowed.[8]

Schizophrenia

In a Cochrane systemic review, senior researcher for the McPin Foundation, Ben Gray found that while Asenapine has some preliminary evidence that it improves positive, negative, and depressive symptoms, it does not have enough research to merit a certain recommendation of Asenapine for the treatment of schizophrenia.[9] Likewise, as stated, Aspenapine isn't approved for schizophrenia treatment in the UK where Cochrane organization and that reviewer is located.

Acute mania

As for its efficacy in the treatment of acute mania, a recent meta-analysis showed that it produces comparatively small improvements in manic symptoms in patients with acute mania and mixed episodes than most other antipsychotic drugs (with the exception of ziprasidone) such as risperidone and olanzapine. Drop-out rates (in clinical trials) were also unusually high with asenapine.[10] According to a post-hoc analysis of two 3-week clinical trials it may possess some antidepressant effects in patients with acute mania or mixed episodes.[11]

Adverse effects

Adverse effect incidence[1][2][3][4]

Note: The discussion below these lists provides some more context into the frequency and severity of these adverse effects.

Very common (>10% incidence) adverse effects include:

Common (1-10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Weight gain

- Increased appetite

- Extrapyramidal side effects (EPS; such as dystonia, akathisia, dyskinesia, muscle rigidity, parkinsonism)

- Sedation

- Dizziness

- Dysgeusia

- Oral hypoaesthesia

- Increased alanine aminotransferase

- Fatigue

Uncommon (0.1-1% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Hyperglycaemia — elevated blood glucose (sugar)

- Syncope

- Seizure

- Dysarthria

- sinus bradycardia

- Bundle branch block

- QTc interval prolongation (has a relatively low risk for causing QTc interval prolongation.[12][13])

- sinus tachycardia

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Hypotension

- Swollen tongue

- Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

- Glossodynia

- Oral paraesthesia

Rare (0.01-0.1% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (Combination of fever, muscle stiffness, faster breathing, sweating, reduced consciousness, and sudden change in blood pressure and heart rate)

- Tardive dyskinesia

- Speech disturbance

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Angioedema

- Blood dyscrasias such as agranulocytosis, leukopenia and neutropenia

- Accommodation disorder

- Pulmonary embolism

- Gynaecomastia

- Galactorrhoea

Unknown incidence adverse effects

- Allergic reaction

- Restless legs syndrome

- Nausea

- Oral mucosal lesions (ulcerations, blistering and inflammation)

- Salivary hypersecretion

- Hyperprolactinaemia

Asenapine seems to have a relatively low weight gain liability for an atypical antipsychotic (which are notorious for their metabolic side effects) and according to a recent meta-analysis it produces significantly less weight gain (SMD [standard mean difference in weight gained in those on placebo vs. active drug]: 0.23; 95% CI: 0.07-0.39) than, paliperidone (SMD: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.27-0.48), risperidone (SMD: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.33-0.50), quetiapine (SMD: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.34-0.53), sertindole (SMD: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.38-0.68), chlorpromazine (SMD: 0.55; 95% CI: 0.34-0.76), iloperidone (SMD: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.49-0.74), clozapine (SMD: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.31-0.99), zotepine (SMD: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.47-0.96) and olanzapine (SMD: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.67-0.81) and approximately (that is, no statistically significant difference at the p=0.05 level) as much as weight gain as aripiprazole (SMD: 0.17; 95% CI: 0.05-0.28), lurasidone (SMD: 0.10; 95% CI: –0.02-0.21), amisulpride (SMD: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.05-0.35), haloperidol (SMD: 0.09; 95% CI: 0.00-0.17) and ziprasidone (SMD: 0.10; 95% CI: –0.02-0.22).[14] Its potential for elevating plasma prolactin levels seems relatively limited too according to this meta-analysis.[14] This meta-analysis also found that asenapine has approximately the same odds ratio (3.28; 95% CI: 1.37-6.69) for causing sedation [compared to placebo-treated patients] as olanzapine (3.34; 95% CI: 2.46-4.50]) and haloperidol (2.76; 95% CI: 2.04-3.66) and a higher odds ratio (although not significantly) for sedation than aripiprazole (1.84; 95% CI: 1.05-3.05), paliperidone (1.40; 95% CI: 0.85-2.19) and amisulpride (1.42; 95% CI: 0.72 to 2.51) to name a few and is hence a mild-moderately sedating antipsychotic.[14] Being a second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic its liability for causing extrapyramidal side effect is comparatively low compared to first-generation antipsychotics such as haloperidol as is supported by the aforementioned meta-analysis (although this meta-analysis did reveal it had a relatively high EPS liability for an atypical antipsychotic drug).[14]

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotics to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[15] Symptoms of withdrawal commonly include nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite.[16] Other symptoms may include restlessness, increased sweating, and trouble sleeping.[16] Less commonly there may be a felling of the world spinning, numbness, or muscle pains.[16] Symptoms generally resolve after a short period of time.[16]

There is tentative evidence that discontinuation of antipsychotics can result in psychosis.[17] It may also result in reoccurrence of the condition that is being treated.[18] Rarely tardive dyskinesia can occur when the medication is stopped.[16]

Pharmacology

| Site | pKi | Ki (nM) | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 8.6 | 2.5 | Partial agonist |

| 5-HT1B | 8.4 | 4.0 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT2A | 10.2 | 0.06 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT2B | 9.8 | 0.16 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT2C | 10.5 | 0.03 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT5A | 8.8 | 1.6 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT6 | 9.5 | 0.25 | Antagonist |

| 5-HT7 | 9.9 | 0.13 | Antagonist |

| α1 | 8.9 | 1.2 | Antagonist |

| α2A | 8.9 | 1.2 | Antagonist |

| α2B | 9.5 | 0.32 | Antagonist |

| α2C | 8.9 | 1.2 | Antagonist |

| D1 | 8.9 | 1.4 | Antagonist |

| D2 | 8.9 | 1.3 | Antagonist |

| D3 | 9.4 | 0.42 | Antagonist |

| D4 | 9.0 | 1.1 | Antagonist |

| H1 | 9.0 | 1.0 | Antagonist |

| H2 | 8.2 | 6.2 | Antagonist |

| mACh | <5 | 8128 | Antagonist |

Asenapine shows high affinity (pKi) for numerous receptors, including the serotonin 5-HT1A (8.6), 5-HT1B (8.4), 5-HT2A (10.2), 5-HT2B (9.8), 5-HT2C (10.5), 5-HT5A (8.8), 5-HT6 (9.5), and 5-HT7 (9.9) receptors, the adrenergic α1 (8.9), α2A (8.9), α2B (9.5), and α2C (8.9) receptors, the dopamine D1 (8.9), D2 (8.9), D3 (9.4), and D4 (9.0) receptors, and the histamine H1 (9.0) and H2 (8.2) receptors. It has much lower affinity (pKi < 5) for the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Asenapine behaves as a partial agonist at the 5-HT1A receptors.[20] At all other targets asenapine is an antagonist.[19] As of November 2010 asenapine is also in clinical trials at UC Irvine to treat stuttering.

Pharmacodynamics

Based on its exceptionally high, unequaled (among antipsychotics) affinity for the 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 receptors, and very high affinity for the α2 and H1 receptors, asenapine, given normal tolerability, should theoretically demonstrate among the highest improvements in the negative symptomology of schizophrenia among all current antipsychotics (August 2017), such as high cognitive improvements and positive, stable mood maintenance.[19]

History

It was developed by Schering-Plough after its November 19, 2007 merger with Organon International. Though Phase III trials began while Organon was still a part of Akzo Nobel.[21] Preliminary data indicate that it has minimal anticholinergic and cardiovascular side effects, as well as minimal weight gain. Over 3000 people have participated in clinical trials of asenapine, and the FDA approved the manufacturer's NDA in August 2009.[22]

References

- "PRODUCT INFORMATION SAPHRIS® (asenapine maleate)" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Merck Sharp & Dohme (Australia) Pty Limited. 14 January 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- "SAPHRIS (asenapine maleate) tablet [Organon Pharmaceuticals USA]". DailyMed. Organon Pharmaceuticals USA. March 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- "Sycrest 5mg and 10mg sublingual tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Lundbeck Limited. 18 April 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- "Product information 21/02/2013 Sycrest -EMEA/H/C/001177 -II/0012" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. N.V. Organon. 21 February 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Minassian, A; Young, JW (August 2010). "Evaluation of the clinical efficacy of asenapine in schizophrenia". Expert Opinion on Pharmacology. 11 (12): 2107–2115. doi:10.1517/14656566.2010.506188. PMC 2924192. PMID 20642375.

- "Saphris (asenapine) prescribing information" (PDF). Schering Corporation. 2009-08-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-11-22. Retrieved 2009-09-05.

- Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- Stoner, Steven (2012). "Asenapine: a clinical review of a second-generation antipsychotic". Clinical Therapeutics. 34 (5): 1023–40. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.03.002. PMID 22494521.

- Hay, A; Byers, A; Sereno, M (2015). "Asenapine versus placebo for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD011458.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011458.pub2. PMC 6464872. PMID 26599405.

- Cipriani, A; Barbui, C; Salanti, G; Rendell, J; Brown, R; Stockton, S; Purgato, M; Spineli, LM; Goodwin, GM; Geddes, JR (October 2011). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 378 (9799): 1306–1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8. PMID 21851976.

- Szegedi, A; Zhao, J; van Willigenburg, A; Nations, KR; Mackle, M; Panagides, J (June 2011). "Effects of asenapine on depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder experiencing acute manic or mixed episodes: a post hoc analysis of two 3-week clinical trials". BMC Psychiatry. 11: 101. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-101. PMC 3152513. PMID 21689438.

- Washington, Nicole B. (October 2012). "Which psychotropics carry the greatest risk of QTc prolongation?". Current Psychiatry. 11 (10): 36–39. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- Taylor, D; Paton, C; Shitij, K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- Leucht, S; Cipriani, A; Spineli, L; Mavridis, D; Orey, D; Richter, F; Samara, M; Barbui, C; Engel, RR; Geddes, JR; Kissling, W; Stapf, MP; Lässig, B; Salanti, G; Davis, JM (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019.

- Joint Formulary Committee, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- Haddad, Peter; Haddad, Peter M.; Dursun, Serdar; Deakin, Bill (2004). Adverse Syndromes and Psychiatric Drugs: A Clinical Guide. OUP Oxford. p. 207-216. ISBN 9780198527480.

- Moncrieff J (July 2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655.

- Sacchetti, Emilio; Vita, Antonio; Siracusano, Alberto; Fleischhacker, Wolfgang (2013). Adherence to Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 85. ISBN 9788847026797.

- Shahid M, Walker GB, Zorn SH, Wong EH (2009). "Asenapine: a novel psychopharmacologic agent with a unique human receptor signature". J. Psychopharmacol. 23 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1177/0269881107082944. PMID 18308814.

- http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=21237275

- "Bipolar Disorder". Clinical Trials Update. Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 2007-06-15. pp. 52, 55.

- "Schering-Plough Announces Asenapine NDA Accepted for Filing by the U.S. FDA" (Press release). Schering-Plough. 2007-11-26. Retrieved 2008-12-29.