Cyclizine

Cyclizine, sold under a number of brand names, is a medication used to treat and prevent nausea, vomiting and dizziness due to motion sickness or vertigo.[2] It may also be used for nausea after general anaesthesia or that which developed from opioid use.[2][3] It is taken by mouth, in the rectum, or injected into a vein.[3][4]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Marezine, Valoid, Nausicalm, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | by mouth, IM, IV |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | N-demethylated to inactive norcyclizine[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 20 hours |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.314 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H22N2 |

| Molar mass | 266.381 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include sleepiness, dry mouth, constipation, and trouble with vision.[5] More serious side effects include low blood pressure and urinary retention.[5] It is not generally recommended in young children or those with glaucoma.[2][6] Cyclizine appears to be safe during pregnancy but has not been well studied.[7] It is in the anticholinergic and antihistamine family of medications.[3][6]

Cyclizine was discovered in 1947.[8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[4] In the United States it is available over the counter.[6] In the United Kingdom 100 tablets costs about £11.26.[9] It is occasionally used for the "high" it can create.[2]

Medical uses

Primary uses include nausea, vomiting and dizziness associated with motion sickness, vertigo and post-operatively following administration of general anesthesia and opioids. It is sometimes given in hyperemesis gravidarum, although the manufacturer advises that it be avoided in pregnancy. Off-license use often occurs with specialists in hospitals to treat inpatients who have become severely dehydrated in pregnancy. An off-label use is as an opioid/opiate potentiator.[10]

The drug Diconal is a combination of cyclizine and the opioid dipipanone.[11] Dipipanone is a schedule I controlled substance in the US, due to its high abuse potential.

Contraindications

Its antimuscarinic action warrants caution in patients with prostatic hypertrophy, urinary retention, or angle-closure glaucoma. Liver disease exacerbates its sedative effects.[10]

Adverse effects

Common (over 10%) — Drowsiness, dry mouth.

Uncommon (1% to 10%) — Headache, psychomotor impairment, dermatitis, and antimuscarinic effects such as diplopia (double vision), tachycardia, constipation, urinary retention and gastro-intestinal disturbances.

Rare (less than 1%) — Hypersensitivity reactions (bronchospasm, angioedema, anaphylaxis, rashes and photosensitivity reactions), extrapyramidal effects, dizziness, confusion, depression, sleep disturbances, tremor, liver dysfunction, and hallucinations.

Pharmacology

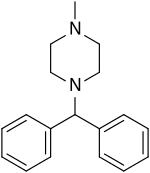

Cyclizine is a piperazine derivative with histamine H1-receptor antagonist (antihistamine) activity. The precise mechanism of action in inhibiting the symptoms of motion sickness is not well understood. It may have effects directly on the vestibular system and on the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Cyclizine exerts a central anticholinergic (antimuscarinic) action.[10]

Synthesis

Cyclizine may be prepared by the Eschweiler–Clarke methylation of diphenylmethylpiperazine or by reaction of benzhydryl bromide with 1-methylpiperazine in acetonitrile to form the hydrobromide salt of the drug.

History

Cyclizine was developed in the American division of pharmacy company Burroughs Wellcome (today GlaxoSmithKline) during a research study involving many drugs of the antihistamine group. Cyclizine was quickly clinically found as a potent and long-acting antiemetic. The company named the substance – or more precisely cyclizine's hydrochloride form which it usually appears in – "marezine hydrochloride" and started to sell it in the United States under trade name Marezine. Selling was begun in France under trade name Marzine in 1965.[12][13]

The substance received more credit when NASA chose it as a space antiemetic for the first occupied moon flight. Cyclizine was introduced to many countries as a common antiemetic. It is an over-the-counter drug in many countries because it has been well tolerated, although it has not been studied much.[12][14]

Society and culture

Some people using methadone recreationally combine cyclizine with their methadone dose, a combination that is known to produce strong psychoactive effects.[15] It has also been used recreationally for its anticholinergic effects to induce hallucinations.[16]

It has also been used illegally in greyhound racing to sabotage a dog's performance.[17]

Names

As cyclizine hydrochloride tablets and cyclizine lactate solution for intramuscular or intravenous injection (brand names: Valoid[10] in UK and South Africa and Marezine, Marzine and Emoquil in US). Cyclizine was marketed as Bonine for Kids in the US, but has been discontinued as of 2012 and replaced with meclizine.[18]

Cyclizine derivatives

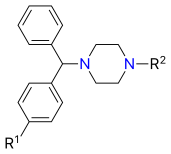

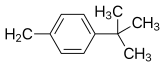

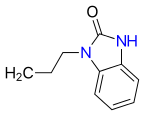

| Structural comparison of cyclizine and related H1 antagonists[19] | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Compound | R1 | R2 |

| Cyclizine | H | CH3 |

| Chlorcyclizine | Cl | CH3 |

| Meclizine | Cl |  |

| Buclizine | Cl |  |

| Oxatomide | H |  |

| Hydroxyzine | Cl | |

| Cetirizine | Cl |  |

See also

References

- "DrugBank: Cyclizine. Pharmacology: metabolism". DrugBank Database. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "Cyclizine 50mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". www.medicines.org.uk. 27 March 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Feldman, Mark; Friedman, Lawrence S.; Brandt, Lawrence J. (2015). Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 218. ISBN 9781455749898. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Cyclizine Side Effects in Detail - Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "Cyclizine: Indications, Side Effects, Warnings - Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "Cyclizine Use During Pregnancy | Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Williams, Peter (2010). The story of the Wellcome Trust : unlocking Sir Henry's legacy to medical research. Hindringham: JJG. p. 14. ISBN 9781899163922. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 272. ISBN 9780857111562.

- "Valoid Tablets by Amdipharm". Electronic Medicines Compendium. Datapharm. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2011-10-01.

- "Diconal Tablets by Amdipharm". Electronic Medicines Compendium. Datapharm. Archived from the original on 2008-04-01. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug discovery: a history. John Wiley & Sons. p. 404. ISBN 0-471-89979-8. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Sittig, Marshall (1988). Pharmaceutical manufacturing encyclopedia. William Andrew. p. 406. ISBN 0-8155-1144-2. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ruben, S. M.; McLean, P. C.; Melville, J. (1989). "Cyclizine abuse among a group of opiate dependents receiving methadone". British Journal of Addiction. 84 (8): 929–934. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00766.x. PMID 2775912.

- Bassett, K.; Schunk, J. E.; Crouch, B. I. (1996). "Cyclizine abuse by teenagers in Utah". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 14 (5): 472–474. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90156-4. PMID 8765114.

- Conor Ryan for The Independent. June 20, 2013 IGB left with €250k bill after dog doping case Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Bonine for Kids". Insight Pharmaceuticals. Archived from the original on 2010-09-17.

- Lemke, Thomas L.; Williams, David A.; Roche, Victoria F.; Zito, S. William, eds. (2013). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health / Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1056. ISBN 1-60913-345-5.