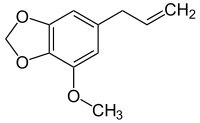

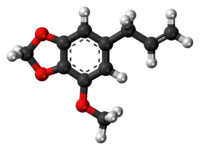

Myristicin

Myristicin (or methoxysafrole) is a phenylpropene, a natural organic compound present in small amounts in the essential oil of nutmeg and anise, in several members of the carrot family, and to a lesser extent in other spices/herbs such as parsley and dill. In such plants, it acts as a natural bioactive agent, specifically as an insecticide or acaricide.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 3-methoxy-4,5-methylenedioxy-allylbenzene; 5-methoxy-3,4-methylenedioxy-allylbenzene |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.009.225 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H12O3 |

| Molar mass | 192.214 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Myristicin is also psychoactive, and acts as an anticholinergic agent. It is a precursor for the illicit synthesis of the psychedelic and empathogenic drug MMDA.

Myristicin is soluble in ethanol and acetone, but insoluble in water.[2]

Uses

Myristicin is a naturally occurring acaricide (agent that kill members of the arachnid subclass Acari, which includes ticks and mites)[1] as well as an apprent general insecticide.[3][1]

Widelski and Kukula-Koch note in a textbook chapter in their 2017 Pharmacognosy that myristicin, "present in the volatile oil of M. fragrans, is a potential chemopreventive agent, by way of its ability to induce the activity of the detoxifying enzyme system, glutathione S-transferase",[4] an activity that is widely discussed[5] alongside a variety of apoptotic, anticancer, and other activities.[4][3]

Myristicin is also known to be a weak inhibitor of monoamine oxidase, a liver enzyme in humans that metabolizes neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin, dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine),[5] and its action, alone and in combination with other drugs, may contribute to circulatory disorders upon its ingestion.[4]

Consumption of nutmeg in large quantities is known to cause hallucinations "followed by unpleasant side effects"; as Widelski and Kukula-Koch further note,

For the psychoactivity of nutmeg to be experienced, the metabolic conversion of the two components of nutmeg essential oil, myristicin and elmicin into compounds similar to amphetamine has to take place... [where] metabolism of myristicin leads to 3-methoxy-4,5-methylenedioxy amphetamine...[4]

The primary literature reports various cases of nutmeg ingestion, including attempts by adolescents trying to achieve a "low cost" high.[4] Such recreational uses of nutmeg as a psychoactive agent have caused acute poisoning that required medical treatment, with symptoms including dry mouth, facial flushing, nausea, vomiting, hypertension, tachycardia, dizziness, anxiety, headache, as well as hallucinations, feelings of euphoria and unreality, delirium, irrational behavior, and collapse.[4][6] Blood myristicin concentrations may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning.[6][4]

Specifically, possible neurotoxic effects on dopaminergic neurons have been reported;[1] more widely, as presented in case reports, raw nutmeg consumption has produced poisoning symptoms where an anticholinergic mechansim attributed to myristicin and elemicin was invoked.[7][8][9]

Myristicin is a known precursor for the chemical synthesis the psychoactive drug, MMDA.[10]

Pharmacology

Raw nutmeg consists of 5-15% essential oil by mass. 4-8.5% of nutmeg essential oil, or 0.2-1.3% of raw nutmeg, is myristicin.[11][7] One study found 20 grams of nutmeg to contain 210 mg myristicin, 70 mg elemicin and 39 mg safrole.[7][12]

While myristicin has been widely accepted as the main psychoactive component of nutmeg (along with elemicin), both the differences in subjective effects observed between nutmeg and synthetic myristicin, as well as the fact that myristicin is not a major component of the seed (therefore is possibly not present in high enough quantities) suggest it does not fully explain the effects of consuming raw nutmeg.[8]

A 1997 study found data to suggest that myristicin can alter the toxicity and / or metabolic pathway of some compounds.[13] A 1963 study found preliminary evidence that myristicin may be a weak monoamine oxidase inhibitor in mice and rats. The study concluded that more direct evidence will be required.[14] In a 2005 study it showed possible neurotoxic effects on cultivated human neuroblastoma cells.[15]

In 1963, Alexander Shulgin speculated myristicin could be metabolized to MMDA, a psychoactive drug related to MDA, in the liver.[8] This speculation remains unconfirmed as of 2009; studies with the closely related compounds asarone and safrole support the conclusion that the proposed transamination reactions do not take place in humans.[16]

References

- https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Myristicin

- "Myristicin". Carcinogens and Tumor Promoters. LKT Laboratories. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- Abourashed, Ehab A.; El-Alfy, Abir T. (2016). "Chemical diversity and pharmacological significance of the secondary metabolites of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans Houtt.)". Phytochem Rev. 15 (6): 1035–1056. doi:10.1007/s11101-016-9469-x. PMC 5222521. PMID 28082856.

- J. Widelski & W.A. Kukula-Koch, "Psychoactive Drugs" (chapter), in Pharmacognosy, 2017, available online via ScienceDirect.

- Robert Tisserand & Rodney Young, in Essential Oil Safety (Second Edition), 2014, available online via ScienceDirect.

- Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1067–1068. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- Shulgin, A. T.; Sargent, T.; Naranjo, C. (1967). "The Chemistry and Psychopharmacology of Nutmeg and of Several Related Phenylisopropylamines" (pdf). Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 4 (3): 13. PMID 5615546.

- Weil, Andrew (1966). "The Use of Nutmeg as a Psychotropic Agent". Bulletin on Narcotics. 1966 (4): 15–23.

- McKenna, A.; Nordt, S. P.; Ryan, J. (2004). "Acute Nutmeg Poisoning". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 11 (4): 240–241. doi:10.1097/01.mej.0000127649.69328.a5. PMID 15249817.

- https://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/motm/myristicin/myristicinh.htm

- "5". Description of components of nutmeg. Nutmeg and Derivatives - Working paper FO-V4084. UN / FAO Forest Department.

- Stafford, P. G.; Bigwood, J. (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Berkeley CA: Ronin Publishing. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-914171-51-5.

- "Myristicin / CAS No. 607-91-0" (PDF). Summary of data for chemical selection. NIH - National Toxicology Program / CSWG. 1997. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-16.

- Truitt Jr, E. B.; Duritz, G.; Ebersberger, E. M. (1963). "Evidence of Monoamine Oxidase Inhibition by Myristicin and Nutmeg". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 112 (3): 647–650. doi:10.3181/00379727-112-28128. PMID 13994372.

- Lee, B. K.; Kim, J. H.; Jung, J. W.; Choi, J. W.; Han, E. S.; Lee, S. H.; Ko, K. H.; Ryu, J. H. (2005). "Myristicin-induced neurotoxicity in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells". Toxicology Letters. 157 (1): 49–56. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.01.012. PMID 15795093.

- Björnstad, K.; Helander, A.; Hultén, P.; Beck, O. (2009). "Bioanalytical Investigation of Asarone in Connection with Acorus calamus Oil Intoxications". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 33 (9): 604–609. doi:10.1093/jat/33.9.604. PMID 20040135.