Droperidol

Droperidol /droʊˈpɛrIdɔːl/ (Inapsine, Droleptan, Dridol, Xomolix, Innovar [combination with fentanyl]) is an antidopaminergic drug used as an antiemetic (that is, to prevent or treat nausea) and as an antipsychotic. Droperidol is also often used as a sedative in intensive-care treatment.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous, Intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 2.3 hours |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.144 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

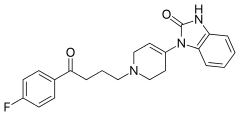

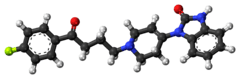

| Formula | C22H22FN3O2 |

| Molar mass | 379.428 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

History

Discovered at Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1961, droperidol is a butyrophenone which acts a potent D2 (dopamine receptor) antagonist with some histamine and serotonin antagonist activity.[1]

Medical use

It has a central antiemetic action and effectively prevents postoperative nausea and vomiting in adults using doses as low as 0.625 mg.

For treatment of nausea and vomiting, droperidol and ondansetron are equally effective; droperidol is more effective than metoclopramide.[2] It has also been used as an antipsychotic in doses ranging from 5 to 10 mg given as an intramuscular injection, generally in cases of severe agitation in a psychotic patient who is refusing oral medication. Its use in intramuscular sedation has been replaced by intramuscular preparations of haloperidol, midazolam, clonazepam and olanzapine. Some practitioners recommend the use of 0.5 mg to 1 mg intravenously for the treatment of vertigo in an otherwise healthy elderly patients who have not responded to Epley maneuvers.

Black box warning

In 2001, the FDA changed the labeling requirements for droperidol injection to include a Black Box Warning, citing concerns of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. The evidence for this is disputed, with 9 reported cases of torsades in 30 years and all of those having received doses in excess of 5 mg.[3] QT prolongation is a dose-related effect,[4] and it appears that droperidol is not a significant risk in low doses. A study in 2015 showed that droperidol is relatively safe and effective for the management of violent and aggressive adult [5]patients in hospital emergency departments in doses of 10mg and above and that there was no increased risk of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes.

Side effects

Dysphoria, sedation, hypotension resulting from peripheral alpha adrenoceptor blockade, prolongation of QT interval which can lead to torsades de pointes, and extrapyramidal side effects such as dystonic reactions/neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[6]

Chemistry

Droperidol is synthesized from 1-benzyl-3-carbethoxypiperidin-4-one,

which is reacted with o-phenylenediamine. Evidently, the first derivative that is formed under the reaction conditions, 1,5-benzodiazepine, rearranges into 1-(1-benzyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydro-4-piridyl)-2-benzymidazolone. Debenzylation of the resulting product with hydrogen over a palladium catalyst, and subsequent alkylation of this using 4-chloro-4'-fluorobutyrophenone yields droperidol.

- C. Janssen, NV Res. Lab., GB 989755 (1962).

- Janssen, P. A. J.; 1963, Belgian Patent BE 626307.

- F.J. Gardocki, J. Janssen, U.S. Patent 3,141,823 (1964).

- P.A.J. Janssen, U.S. Patent 3,161,645 (1964).

(See pimozide article for proposed mechanism of intramolecular rearrangement.)

References

- Peroutka SJ, Synder SH (December 1980). "Relationship of neuroleptic drug effects at brain dopamine, serotonin, alpha-adrenergic, and histamine receptors to clinical potency". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (12): 1518–22. doi:10.1176/ajp.137.12.1518. PMID 6108081. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- Domino KB, Anderson EA, Polissar NL, Posner KL (June 1999). "Comparative efficacy and safety of ondansetron, droperidol, and metoclopramide for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 88 (6): 1370–9. doi:10.1213/00000539-199906000-00032. PMID 10357347.

- Kao LW, Kirk MA, Evers SJ, Rosenfeld SH (April 2003). "Droperidol, QT prolongation, and sudden death: what is the evidence?". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 41 (4): 546–58. doi:10.1067/mem.2003.110. PMID 12658255.

- Lischke V, Behne M, Doelken P, Schledt U, Probst S, Vettermann J (November 1994). "Droperidol causes a dose-dependent prolongation of the QT interval". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 79 (5): 983–6. doi:10.1213/00000539-199411000-00028. PMID 7978420.

- Calver, Leonie; Page, Colin; Downes, Michael; Chan, Betty; Kinnear, Frances; Wheatley, Luke; Spain, David; Ibister, Geoffrey (September 2015). "The safety and effectiveness of droperidol for sedation of acute behavioral disturbance in the emergency department". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 66 (3): 231–238. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- Park CK, Choi HY, Oh IY, Kim MS (2002). "Acute dystonia by droperidol during intravenous patient-controlled analgesia in young patients". J. Korean Med. Sci. 17 (5): 715–7. doi:10.3346/jkms.2002.17.5.715. PMC 3054934. PMID 12378031.

Further reading

- Scuderi PE (2003). "Droperidol: Many questions, few answers". Anesthesiology. 98 (2): 289–90. doi:10.1097/00000542-200302000-00002. PMID 12552182.

- Lischke V, Behne M, Doelken P, Schledt U, Probst S, Vettermann J. Droperidol causes a dose-dependent prolongation of the QT interval. Department of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University Clinics, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

- Emergency Medicine Magazine : https://web.archive.org/web/20110527190715/http://www.emedmag.com/html/pre/tri/1005.asp