Opipramol

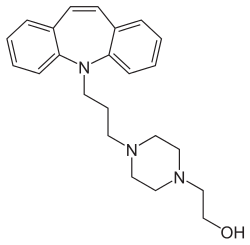

Opipramol, sold under the brand name Insidon among others, is an anxiolytic and antidepressant which is used throughout Europe.[1][3][4][5][6] Although it is a member of the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), opipramol is atypical among TCAs and its primary mechanism of action is much different in comparison.[6] Most TCAs act as monoamine reuptake inhibitors, but opipramol does not, and instead acts primarily as a sigma receptor agonist.[6] It is a dibenzazepine (iminostilbene) derivative. Opipramol was developed by Schindler and Blattner in 1961.[7]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Insidon, others |

| Other names | G-33040; RP-8307[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 94%[2] |

| Protein binding | 91%[2] |

| Metabolism | CYP2D6-mediated[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 6–11 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Urine (70%), feces (10%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.687 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H29N3O |

| Molar mass | 363.505 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Medical uses

Opipramol is typically used in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and somatoform disorders.[2][5] Its anxiolysis becomes prominent after only one to two weeks of chronic administration. Upon first commencing treatment, opipramol is rather sedating in nature due to its antihistamine properties, but this effect becomes less prominent with time.

Contraindications

- In patients with hypersensitivity to opipramol or another component of the formulation

- Acute alcohol, sedative, analgesic, and antidepressant intoxications

- Acute urinary retention

- Acute delirium

- Untreated narrow-angle glaucoma

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia with residual urinary retention

- Paralytic ileus

- Pre-existing higher-grade atrioventricular blockages or diffuse supraventricular or ventricular stimulus conduction disturbances

- Combination with monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI)

Pregnancy and lactation

Experimental animal studies did not indicate injurious effects of opipramol on the embryonic development or fertility. Opipramol should only be prescribed during pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester, for compelling indication. It should not be used during lactation and breastfeeding, since it passes into breast milk in small quantities.

Side effects

The frequently (≥1% to <10%) reported adverse reactions with opipramol especially at the beginning of the treatment include fatigue, dry mouth, blocked nose, hypotension, and orthostatic dysregulation.

The adverse reactions reported occasionally(≥0.1% to <1%) include dizziness, stupor, micturition disturbances, accommodation disturbances, tremor, weight gain, thirst, allergic skin reactions (rash, urticaria), abnormal ejaculation, erectile impotence, constipation, transient increases in liver enzyme activities, tachycardia, and palpitations.

Rarely (≥0.01% to <0.1%) reported adverse reaction includes excitation, headache, paresthesia especially in elderly patients, restlessness, sweating, sleep disturbances, edema, galactorrhea, urine blockage, nausea and vomiting, collapse conditions, stimulation conducting disturbances, intensification of present heart insufficiency, blood profile changes particularly leukopenia, confusion, delirium, stomach complaints, taste disturbance, and paralytic ileus especially with sudden discontinuation of a longer-term high-dose therapy.

Very rarely (<0.01%) adverse reaction includes seizures, motor disorder, (akathisia, dyskinesia), ataxia, polyneuropathy, glaucoma, anxiety, hair loss, agranulocytosis, severe liver dysfunction after long-term treatment, jaundice, and chronic liver damage.

Overdose

Symptoms of intoxication from overdose include drowsiness, insomnia, stupor, agitation, coma, transient confusion, increased anxiety, ataxia, convulsions, oliguria, anuria, tachycardia or bradycardia, arrhythmia, AV block, hypotension, shock, respiratory depression, and, rarely, cardiac arrest.

As therapy of intoxication, specific antidote is not available, removal of the drug by vomiting or gastric lavage should be done. Continuous cardiovascular monitoring for at least 48 hours should be done. In case of respiratory failure due to overdose, intubation and artificial respiration should be done. During severe hypotension due to overdose, corresponding recumbent positioning, plasma expander, dopamine or dobutamine as drops-infusion should be initiated. In heart rhythm disturbances, individualized treatment should be done where appropriate pacemaker and compensation in low potassium levels and possible acidosis should be done. While in convulsions due to overdose, administration of intravenous diazepam or another anticonvulsant agent such as phenobarbital or paraldehyde should be done though intensification of existing respiratory insufficiency, hypotension, or coma may happen.

Interactions

The therapy with opipramol indicates an additional therapy with antipsychotics, hypnotics, and other anxiolytics (e.g. barbiturates, benzodiazepines). Therefore, some specific reactions, particularly central nervous system depressant effects, could be intensified and an intensification of common side effects may occur. If necessary the dosage may be reduced. Co-administration with alcohol can cause stupor.

MAOIs should be discontinued at least 14 days before the treatment with opipramol. Concomitant use of opipramol with beta blockers, antiarrhythmics (of class 1c), as well as drugs from the TCA group and preparations which influence the microsomal enzyme system, can lead to changes in plasma concentrations of these drugs. Co-administration of antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol, risperidone) can increase the plasma concentration of opipramol. Barbiturates and anticonvulsants can reduce the plasma concentration of opipramol and thereby weaken the therapeutic effect.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| σ1 | 0.2–50 | Rodent | [9][10][11] |

| σ2 | 110 | ND | [12] |

| SERT | ≥2,200 | Rat/? | [13][14][15] |

| NET | ≥700 | Rat/? | [13][14][15] |

| DAT | ≥3,000 | Rat/? | [13][14][15] |

| 5-HT1A | >10,000 | ? | [15] |

| 5-HT2A | 120 | ? | [15] |

| 5-HT2C | ND | ND | ND |

| α1 | 200 | ? | [15] |

| α2 | 6,100 | ? | [15] |

| D1 | 900 | Rat | [11] |

| D2 | 120–300 | Rat | [15][11] |

| H1 | 6.03 | Human | [16] |

| H2 | 4,470 | Human | [16] |

| H3 | 61,700 | Human | [16] |

| H4 | >100,000 | Human | [16] |

| mACh | 3,300 | ? | [15] |

| NMDA/PCP | >30,000 | Rat | [11] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Opipramol acts as a high affinity sigma receptor agonist, primarily of the σ1 subtype, but also of the σ2 subtype with lower affinity.[5][2] In one study of σ1 receptor ligands that also included haloperidol, pentazocine, (+)-3-PPP, ditolylguanidine, dextromethorphan, SKF-10,047 ((±)-alazocine), ifenprodil, progesterone, and others, opipramol showed the highest affinity (Ki = 0.2–0.3) for the guinea pig σ1 receptor of all the tested ligands except haloperidol, which it was approximately equipotent with.[9] The sigma receptor agonism of opipramol is thought to be responsible for its therapeutic benefits against anxiety and depression.[6][2]

Unlike other TCAs, opipramol does not inhibit the reuptake of serotonin or norepinephrine.[2] However, it does act as a high affinity antagonist of the histamine H1 receptor[16] and as a low to moderate affinity antagonist of the dopamine D2, serotonin 5-HT2, and α1-adrenergic receptors.[2][15] H1 receptor antagonism accounts for its antihistamine effects and associated sedative side effects.[5][2] In contrast to other TCAs, opipramol has very low affinity for the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and virtually no anticholinergic effects.[15][17]

Sigma receptors are a set of proteins located in the endoplasmic reticulum.[2] σ1 receptors play key role in potentiating intracellular calcium mobilization thereby acting as sensor or modulator of calcium signaling.[2] Occupancy of σ1 receptors by agonists causes translocation of the receptor from endoplasmic reticulum to peripheral areas (membranes) where the σ1 receptors cause neurotransmitter release.[2] Opipramol is said to have a biphasic action, with prompt initial improvement of tension, anxiety, and insomnia followed by improved mood later.[2] Hence, it is an anxiolytic with an antidepressant component.[2] After sub-chronic treatment with opipramol, σ2 receptors are significantly downregulated but σ1 receptors are not.[2]

Pharmacokinetics

Opipramol is rapidly and completely absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract.[2] The bioavailability of opipramol amounts to 94%.[2] After single oral administration of 50 mg, the peak plasma concentration of the drug is reached after 3.3 hours and amounts to 15.6 ng/mL.[2] After single oral administration of 100 mg the maximum plasma concentration is reached after 3 hours and amounts to 33.2 ng/mL.[2] Therapeutic concentrations of opipramol range from 140 to 550 nmol/L.[18] The plasma protein binding amounts to approximately 91% and the volume of distribution is approximately 10 L/kg.[2] Opipramol is partially metabolized in the liver to deshydroxyethylopipramol.[2] Metabolism occurs through the CYP2D6 isoenzyme.[2] Its terminal half-life in plasma is 6–11 hours.[2] About 70% is eliminated in urine with 10% unaltered.[2] The remaining portion is eliminated through feces.[2]

History

Opipramol was developed by Geigy.[19] It first appeared in the literature in 1952 and was patented in 1961.[19] The drug was first introduced for use in medicine in 1961.[19] Opipramol was one of the first TCAs to be introduced, with imipramine marketed in the 1950s and amitriptyline marketed in 1961.[19]

Society and culture

References

- J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 904–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- Mohapatra, S; Rath, NM; Agrawal, A; Verma, J (October 2013). "Opipramol: A Novel Drug" (PDF). Delhi Psychiatry Journal. 16 (2): 409–411.

- Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 760–761. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- "Opipramol".

- Möller HJ, Volz HP, Reimann IW, Stoll KD (February 2001). "Opipramol for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled trial including an alprazolam-treated group". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 21 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1097/00004714-200102000-00011. PMID 11199949.

- Müller WE, Siebert B, Holoubek G, Gentsch C (November 2004). "Neuropharmacology of the anxiolytic drug opipramol, a sigma site ligand". Pharmacopsychiatry. 37 (Suppl 3): S189–197. doi:10.1055/s-2004-832677. PMID 15547785.

- Grosser HH, Ryan E (1965). "Drug Treatment of Anxiety: A Controlled Study of Opipramol and Chlordiazepoxide". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 111 (471): 134–141. doi:10.1192/bjp.111.471.134. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 14270525.

- Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Hanner M, Moebius FF, Flandorfer A, Knaus HG, Striessnig J, Kempner E, Glossmann H (1996). "Purification, molecular cloning, and expression of the mammalian sigma1-binding site". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (15): 8072–7. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.8072H. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.15.8072. PMC 38877. PMID 8755605.

- Klein M, Musacchio JM (1989). "High affinity dextromethorphan binding sites in guinea pig brain. Effect of sigma ligands and other agents". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 251 (1): 207–15. PMID 2477524.

- Rao TS, Cler JA, Mick SJ, Dilworth VM, Contreras PC, Iyengar S, Wood PL (1990). "Neurochemical characterization of dopaminergic effects of opipramol, a potent sigma receptor ligand, in vivo". Neuropharmacology. 29 (12): 1191–7. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(90)90044-r. PMID 1963476.

- Sills MA, Loo PS (1989). "Tricyclic antidepressants and dextromethorphan bind with higher affinity to the phencyclidine receptor in the absence of magnesium and L-glutamate". Mol. Pharmacol. 36 (1): 160–5. PMID 2568580.

- Hyttel J (1982). "Citalopram--pharmacological profile of a specific serotonin uptake inhibitor with antidepressant activity". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 6 (3): 277–95. doi:10.1016/s0278-5846(82)80179-6. PMID 6128769.

- Boulton, Alan A.; Baker, Glen B.; Coutts, Ronald T. (1988). Analysis of Psychiatric Drugs. 10. p. 336. doi:10.1385/0896031217. ISBN 978-0-89603-121-0.

- Holoubek G, Müller WE (2003). "Specific modulation of sigma binding sites by the anxiolytic drug opipramol". J Neural Transm (Vienna). 110 (10): 1169–79. doi:10.1007/s00702-003-0019-5. PMID 14523629.

- Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H₁R, H₂R, H₃R, and H₄R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 385 (2): 145–70. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803.

- Luis M. Botana; Mabel Loza (20 April 2012). Therapeutic Targets: Modulation, Inhibition, and Activation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-1-118-18552-0.

- Gutteck U, Rentsch KM (2003). "Therapeutic drug monitoring of 13 antidepressant and five neuroleptic drugs in serum with liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry". Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 41 (12): 1571–9. doi:10.1515/CCLM.2003.240. PMID 14708881.

- Andersen J, Kristensen AS, Bang-Andersen B, Strømgaard K (2009). "Recent advances in the understanding of the interaction of antidepressant drugs with serotonin and norepinephrine transporters". Chem. Commun. (25): 3677–92. doi:10.1039/b903035m. PMID 19557250.

- I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 209–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.