Curare

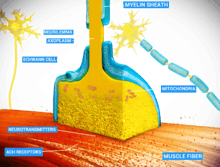

Curare /kʊˈrɑːri/[1] or /kjʊˈrɑːri/[2] is a common name for various plant extract alkaloid arrow poisons originating from Central and South America. These poisons function by competitively and reversibly inhibiting the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR), which is a subtype of acetylcholine receptor found at the neuromuscular junction. This causes weakness of the skeletal muscles and, when administered in a sufficient dose, eventual death by asphyxiation due to paralysis of the diaphragm.

According to pharmacologist Rudolf Boehm's 1895 classification scheme, the three main types of curare are:[3]

- tube or bamboo curare: so named because of its packing into hollow bamboo tubes—of which the main toxin is D-tubocurarine—derived from Chondrodendron and other genera in the Menispermaceae.

- pot curare: originally packed in terra cotta pots—of which the main alkaloid components are protocurarine, protocurine, and protocuridine (but see below re: inaccuracy/ambiguity of early analyses)(Protocurarine being the active ingredient; protocurine only weakly toxic, and protocuridine non-toxic). Comprising extracts from both Menispermaceae and Loganiaceae/Strychnaceae.

- calabash or gourd curare (originally packed into hollow gourds—of which the main toxin is C toxiferine I). Comprising extracts from Loganiaceae/Strychnaceae alone.

Of these three types, some formulae referable to tube curare are the most toxic, relative to their LD50 values.[3]

Although this tripartite classification of curares into 'tube', 'pot' and 'calabash' was initially useful, it rapidly became outmoded:

Gill found that Boehm's classification became invalid shortly after his investigations, because the Indians began to use various types of containers for their preparations [i.e. were not consistent in their use of the three types of container for three distinct types of poison].[4]

Thus Manske in The Alkaloids in 1955, where he also observes:

The results of the early [pre-1900] work were very inaccurate because of the complexity and variation of the composition of the mixtures of alkaloids involved...these were impure, non-crystalline alkaloids...Almost all curare preparations were and are complex mixtures, and many of the physiological actions attributed to the early curarizing preparations were undoubtedly due to impurities, particularly to other alkaloids present. The curare preparations are now considered to be of two main types, those from Chondrodendron or other members of the Menispermaceae family and those from Strychnos, a genus of the Loganiaceae [ now Strychnaceae ] family. Some preparations may contain alkaloids from both...and the majority have other secondary ingredients.[4]

History

_(14784389962).jpg)

Curare was used as a paralyzing poison by South American indigenous people. The prey was shot by arrows or blowgun darts dipped in curare, leading to asphyxiation owing to the inability of the victim's respiratory muscles to contract. The word 'curare' is derived from wurari, from the Carib language of the Macusi Indians of Guyana.[5] Curare is also known among indigenous peoples as Ampi, Woorari, Woorara, Woorali, Wourali, Wouralia, Ourare, Ourari, Urare, Urari, and Uirary.

In 1596, Sir Walter Raleigh mentioned the arrow poison in his book Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana (which relates to his travels in Trinidad and Guayana), though the poison he described possibly was not curare.[6] In 1780, Abbe Felix Fontana discovered that it acted on the voluntary muscles rather than the nerves and the heart.[7] In 1832, Alexander von Humboldt gave the first western account of how the toxin was prepared from plants by Orinoco River natives.[8]

During 1811–1812, Sir Benjamin Collins Brody (1783–1862) experimented with curare.[9] He was the first to show that curare does not kill the animal and the recovery is complete if the animal's respiration is maintained artificially. In 1825, Charles Waterton described a classical experiment in which he kept a curarized female donkey alive by artificial respiration with a bellows through a tracheostomy.[10] Waterton is also credited with bringing curare to Europe.[11] Robert Hermann Schomburgk, who was a trained botanist, identified the vine as one of the genus Strychnos and gave it the now accepted name Strychnos toxifera.[12]

George Harley (1829–1896) showed in 1850 that curare (wourali) was effective for the treatment of tetanus and strychnine poisoning.[13][14] In 1857, Claude Bernard (1813–1878) published the results of his experiments in which he demonstrated that the mechanism of action of curare was a result of interference in the conduction of nerve impulses from the motor nerve to the skeletal muscle, and that this interference occurred at the neuromuscular junction.[3][15] From 1887, the Burroughs Wellcome catalogue listed under its 'Tabloids' brand name, tablets of curare at 1⁄12 grain (price 8 shillings) for use in preparing a solution for hypodermic injection. In 1914, Henry Hallett Dale (1875–1968) described the physiological actions of acetylcholine.[16] After 25 years, he showed that acetylcholine is responsible for neuromuscular transmission, which can be blocked by curare.[17]

The best known and historically most important (because of its medical applications) toxin is d-tubocurarine. It was isolated from the crude drug—from a museum sample of curare—in 1935 by Harold King (1887–1956) of London, working in Sir Henry Dale's laboratory. He also established its chemical structure.[18]. Pascual Scannone, a Venezuelan anesthesiologist who trained and specialized in New York City, USA, did extensive research on curare as a possible paralyzing agent for patients during surgical procedures. In 1942, he became the first person in all of Latin America to use curare during a medical procedure when he successfully performed a tracheal intubation in a patient to whom he administed curare for muscle paralysis at the “El Algodonal Hospital” in Caracas, Venezuela. After its introduction in 1942, curare/curare-derivatives have become a widely used paralyzing agent during medical and surgical procedures to this day.

Curare is active—toxic or muscle-relaxing, depending on the intended use—only by an injection or a direct wound contamination by poisoned dart or arrow. It is harmless if taken orally[10][19] because curare compounds are too large and highly charged to pass through the lining of the digestive tract to be absorbed into the blood. For this reason, people can eat curare-poisoned prey safely. In medicine, curare has been superseded by a number of curare-like agents, such as pancuronium, which have a similar pharmacodynamic profile, but fewer side effects.

Classification and chemical structure

The various components of curare are organic compounds classified as either isoquinoline or indole alkaloids. Tubocurarine is the major active component in the South American dart poison.[20] As an alkaloid, tubocurarine is a naturally occurring compound that consists of nitrogenous bases—though the chemical structure of alkaloids is highly variable.

Like most alkaloids, tubocurarine consists of a cyclic system with a nitrogen atom in an amine group.[21] Because of this structure, tubocurarine can bind readily to the receptors for acetylcholine (ACh) at the neuromuscular junction, which blocks nerve impulses from being sent to the skeletal muscles, effectively paralyzing the muscles of the body. Since tubocurarine binds reversibly to the ACh receptors, treatment for curare poisoning involves adding an acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor, which will stop the destruction of acetylcholine so that it can compete with curare.[22]

Pharmacological properties

Curare is an example of a non-depolarizing muscle relaxant that blocks the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR),[23] one of the two types of acetylcholine (ACh) receptors, at the neuromuscular junction. The main toxin of curare, d-tubocurarine, occupies the same position on the receptor as ACh with an equal or greater affinity, and elicits no response, making it a competitive antagonist. The antidote for curare poisoning is an acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor (anti-cholinesterase), such as physostigmine or neostigmine. By blocking ACh degradation, AChE inhibitors raise the amount of ACh in the neuromuscular junction; the accumulated ACh will then correct for the effect of the curare by activating the receptors not blocked by toxin at a higher rate.

The time of onset varies from within one minute (for tubocurarine in intravenous administration, penetrating a larger vein), to between 15 and 25 minutes (for intramuscular administration, where the substance is applied in muscle tissue).[24]

Curare has no effect if ingested so the meat of an animal killed by curare does not become poisonous, and it has no effect on its flavor.[25]

Anesthesia

Isolated attempts to use curare during anesthesia date back to 1912 by Arthur Lawen of Leipzig,[26] but curare came to anesthesia via psychiatry (electroplexy). In 1939 Abram Elting Bennett used it to modify metrazol induced convulsive therapy.[27] Muscle relaxants are used in modern anesthesia for many reasons, such as providing optimal operating conditions and facilitating intubation of the trachea. Before muscle relaxants, anesthesiologists needed to use larger doses of the anesthetic agent, such as ether, chloroform or cyclopropane to achieve these aims. Such deep anesthesia risked killing patients who were elderly or had heart conditions.

The source of curare in the Amazon was first researched by Richard Evans Schultes in 1941. Since the 1930s, it was being used in hospitals as a muscle relaxant. He discovered that different types of curare called for as many as 15 ingredients, and in time helped to identify more than 70 species that produced the drug.

In the 1940s, it was used on a few occasions during surgery as it was mistakenly thought to be an analgesic or anesthetic. The patients reported feeling the full intensity of the pain though they were not able to do anything about it since they were essentially paralyzed.[28]

On January 23, 1942, Harold Griffith and Enid Johnson gave a synthetic preparation of curare (Intercostrin/Intocostrin) to a patient undergoing an appendectomy (to supplement conventional anesthesia). Safer curare derivatives, such as rocuronium and pancuronium, have superseded d-tubocurarine for anesthesia during surgery. When used with halothane d-tubocurarine can cause a profound fall in blood pressure in some patients as both the drugs are ganglion blockers.[29] However, it is safer to use d-tubocurarine with ether.

In 1954, an article was published by Beecher and Todd suggesting that the use of muscle relaxants (drugs similar to curare) increased death due to anesthesia nearly sixfold.[30] This was refuted in 1956.[31]

Modern anesthetists have at their disposal a variety of muscle relaxants for use in anesthesia. The ability to produce muscle relaxation irrespective of sedation has permitted anesthetists to adjust the two effects independently and on the fly to ensure that their patients are safely unconscious and sufficiently relaxed to permit surgery. The use of neuromuscular blocking drugs carries with it the risk of anesthesia awareness.

Plant sources

There are dozens of plants from which isoquinoline and indole alkaloids with curarizing effects can be isolated, and which were utilized by indigenous tribes of Central and South America for the production of arrow poisons. Among them are:

In family Menispermaceae:

- Genus Chondrodendron notably C. tomentosum

- Genus Curarea, species toxicofera and tecunarum

- Genus Sciadotenia toxifera

- Genus Telitoxicum

- Genus Abuta

- Genus Caryomene

- Genus Anomospermum

- Genus Orthomene

- Genus Cissampelos, section L. (Cocculeae) of genus

Other families:

- several species of the genus Strychnos of family Loganiaceae including toxifera, guianensis, castelnaei, usambarensis

- a plant in the subfamily Aroideae of family Araceae called taja

- at least three members of the genus Artanthe of family Piperaceae

- Paullinia cururu in the family Sapindaceae[32]

Some plants in the family Aristolochiaceae have also been reported as sources.

Alkaloids with curare-like activity are present in plants belonging to the fabaceous genus Erythrina.[33]

Toxicity

The toxicity of curare alkaloids in humans hasn't been established. Administration must be parenterally, as gastro-intestinal absorption is ineffective.

LD50 (mg/kg)

human: 0.735 est. (form and method of administration not indicated)

mouse: pot: 0.8–25; tubo: 5-10; calabash: 2–15.

Preparation

Traditionally prepared curare is a dark, heavy, viscid paste with a very bitter taste.[34] In 1938, Richard Gill and his expedition collected samples of processed curare and described its method of traditional preparation; one of the plant species used at that time was Chondrodendron tomentosum.[35]

Adjuvants

It is known that the final preparation is often more potent than the concentrated principal active ingredient. Various irritating herbs, stinging insects, poisonous worms, and various parts of amphibians and reptiles are added to the preparation. Some of these accelerate the onset of action or increase the toxicity; others prevent the wound from healing or blood from coagulating.

Diagnosis and management of curare poisoning

Curare poisoning can be indicated by typical signs of neuromuscular-blocking drugs such as paralysis including respiration but not directly affecting the heart.

Curare poisoning can be managed by artificial respiration such as mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. In a study of 29 army volunteers that were paralyzed with curare, artificial respiration managed to keep an oxygen saturation of always above 85%,[36] a level at which there is no evidence of altered state of consciousness.[37] Yet, curare poisoning mimics the total locked-in syndrome in that there is paralysis of every voluntarily controlled muscle in the body (including the eyes), making it practically impossible for the victim to confirm consciousness while paralyzed.[38]

Spontaneous breathing is resumed after the end of the duration of action of curare, which is generally between 30 minutes[39] to 8 hours,[40] depending on the variant of the toxin and dosage. Cardiac muscle is not directly affected by curare, but if more than four to six minutes has passed since respiratory cessation the cardiac muscle may stop functioning by oxygen-deprivation, making cardiopulmonary resuscitation including chest compressions necessary.[41]

Antidote

Muscle paralysis can be reversed by administration of a cholinesterase inhibitor such as pyridostigmine,[42] neostigmine and edrophonium. These can be termed "anticurare" drugs.

Gallery

Abuta selloana. Certain species in the menispermaceous genus Abuta—particularly the Colombian species A. imene—have sometimes been used in the preparation of curare.

Abuta selloana. Certain species in the menispermaceous genus Abuta—particularly the Colombian species A. imene—have sometimes been used in the preparation of curare. Anomospermum schomburgkii. Certain species in the genus Anomospermum have been used in the preparation of some forms of curare.

Anomospermum schomburgkii. Certain species in the genus Anomospermum have been used in the preparation of some forms of curare. Cissampelos pareira. Certain species in the genus Cissampelos have been employed in the preparation of curare.

Cissampelos pareira. Certain species in the genus Cissampelos have been employed in the preparation of curare.

See also

- Arrow poison, what curare was originally used for

- Poison dart frog, another source of arrow poison

- Strychnine, a related alkaloid poison that occurs in some of the same plants as curare

Citations

- "curare". The American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing.

- "curare". Oxford Online Dictionaries.

- Gray, TC (1947). "The Use of D-Tubocurarine Chloride in Anæsthesia". Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1 (4): 191–203. PMC 1940167. PMID 19309828.

- R. H. F. Manske (ed.) (1955). The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Physiology Volume 5: Pharmacology. New York: Academic Press/Guelph, Ontario: Dominion Rubber Research Laboratory.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- Carman J. A. Anaesthesia 1968, 23, 706.

- The Gale Encyclopedia of Science. Third Edition.

- Humboldt, Alexander von. Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America, During the Year 1799–1804 Volume 2.

- Phil. Trans. 1811, 101, 194; 1812, 102, 205.

- "Loading..." www.yeoldelog.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- Reprinted in "Classical File", Survey of Anesthesiology 1978, 22, 98.

- Waterton and Wouralia. British Journal of Pharmacology (1999) 126, 1685–1689

- Paton A. Practitioner 1979, 223, 849

- "Whonamedit – dictionary of medical eponyms". www.whonamedit.com.

- Bernard, C (1857). "Vingt-cinquième Leçon". Leçons sur les effets des substances toxiques et médicamenteuses (in French). Paris: J.B. Baillière. pp. 369–80.

- Dale H. H. J. Pharmac. Exp. Ther. 1914, 6, 147.

- Dale H. H. Br. Med. J. 1934, 1, 835

- King H. J. Chem. Soc. 1935, 57, 1381; Nature, Lond. 1935, 135, 469

- "Curare – Chondrodendron tomentosum". www.blueplanetbiomes.org.

- http://www.britannica.com/science/curare Encyclopædia Britannica 01 Dec. 2015

- Ethnopharmacology and systems biology: A perfect holistic match, Verpoorte, R. 2005

- Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy and Physiology The Unity of Form and Function. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Education, 2015. Print.

- https://www.drugs.com/mmx/curare.html

- "Curare". Drugs.com. 2001-11-08.

- From the Rainforests of South America to The Operating Room: A History of Curare, By Daniel Milner, BA, CD, Summer 2009. University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine.

- Lawen A. Beitr. klin. Chir. 1912, 80, 168.

- Bennett A. E. J. Am. Med. Ass. 1940, 114, 322

- Dennett, Daniel C. Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology (1978), Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, p209

- Mashraqui S. Hypotension induced with d-tubocurarine and halothane for surgery of patent ductus arteriosus. Indian Journal of Anesthesia. 1994 Oct; 42(5): 346-50

- Beecher H. K.; Todd D. P. (1954). "A Study of the Deaths Associated with Anesthesia and Surgery : Based on a Study of 599,548 Anesthesias in Ten Institutions 1948–1952, Inclusive". Annals of Surgery. 140 (2): 2–35. doi:10.1097/00000658-195407000-00001. PMC 1609600. PMID 13159140.

(reprinted in "Classical File", Survey of Anesthesiology 1971, 15, 394, 496)

- Albertson HA, Trout HH, Morfin E (June 1956). "The Safety of Curare in Anesthesia'". Annals of Surgery. 143 (6): 833–837. doi:10.1097/00000658-195606000-00012. PMC 1465152. PMID 13327828.

- Lewis, Walter H. and Elvin-Lewis, Memory P.F. Medical Botany : Plants Affecting Man's Health, pub. Wiley-Interscience 1977 ISBN 0-471-53320-3

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=DvbJCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA269&lpg=PA269&dq=protocurarine#v=onepage&q=protocurarine&f=false Retrieved 13.23 on 12/11/18

- Curare, a South American Arrow Poison Archived 2012-07-28 at the Wayback Machine, from "Plants and Civilization" by Professor Arthur C. Gibson, at UCLA Mildred E. Mathias Botanical Garden.

- Kemp, Christopher (17 January 2018). "The Amazonian arrow poison that made modern anaesthesia". New Scientist (3161).

- Page 520 in: Paradis, Norman A. (2007). Cardiac arrest: the science and practice of resuscitation medicine. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84700-1.

- Oxymoron: Our Love-Hate Relationship with Oxygen, By Mike McEvoy at Albany Medical College, New York. 10/12/2010

- Page 357 in: Damasio, Antonio R. (1999). The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness. San Diego: Harcourt Brace. ISBN 978-0-15-601075-7.

- For therapeutic dose of tubocurarine by shorter limit as given at page 151 in: Rang, H. P. (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-07145-4. OCLC 51622037.

- For 20-fold paralytic dose of toxiferine ("calabash curare"), according to: Page 330 in: The Alkaloids: v. 1: A Review of Chemical Literature (Specialist Periodical Reports). Cambridge, Eng: Royal Society of Chemistry. 1971. ISBN 978-0-85186-257-6.

- "four to six minutes" given from: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) in Farlex medical dictionary, in turn citing Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008.

- Page 153 in: Thomas Morgan III; Bernadette Kalman (2007). Neuroimmunology in Clinical Practice. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5840-4.

References

- Foldes, F. F. "Anesthesia before and after curare" (translation), Anasthesieabteilung des Albert-Einstein-College of Medicine. Anaesthesiol Reanim, 1993, 18(5):128–31. PMID 8280340. Retrieved June 20, 2005. Original title: "Anästhesie vor und nach Curare".

- James, Mel. "Harold Griffith", Canada Heirloom Series, Volume 6. Retrieved June 20, 2005.

- Schaffner, Brynn (2000). "Curare". Blue Planet Biomes. Retrieved September 27, 2005.

- Smith, Roger. "Cholernergic Transmission", retrieved March 13, 2007

- Strecker, G. J., et al. "Curare binding and the curare-induced subconductance state of the acetylcholine receptor channel", Biophysical Journal 56(4): 795–806 (October 1989). doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82726-2. PMC 1280535. PMID 2479422. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

External links

- Harold Griffith Fonds, P090. Osler Library of the History of Medicine. McGill University Library. Contains papers and records pertaining to his introduction of curare into anesthesiology.

- Raghavendra, Thandla. "Neuromuscular blocking drugs: discovery and development". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. July 2002; 95(7): 363–367. PMC 1279945. PMID 12091515.

- Waterton, Charles. A. H. Bullen (ed.). Wanderings in South America.