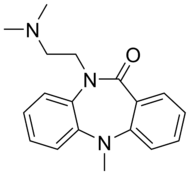

Dibenzepin

Dibenzepin, sold under the brand name Noveril among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) used widely throughout Europe for the treatment of depression.[1][2][3] It has similar efficacy and effects relative to other TCAs like imipramine but with fewer side effects.[4][5][6][7]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Noveril, Anslopax, Deprex, Ecatril, Neodit, Victoril |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 25% |

| Protein binding | 80% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 5 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (80%), feces (20%) |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H21N3O |

| Molar mass | 295.379 g/mol g·mol−1 |

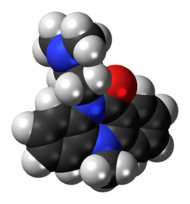

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Medical uses

Dibenzepin is used mainly in the treatment of major depressive disorder.

Like other TCAs, dibenzepin may have potential use in the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain.

Overdose

As TCAs have a relatively narrow therapeutic index, the likelihood of overdose (both accidental and intentional) is fairly high and should be considered carefully by the prescribing physician prior to patient use. Symptoms of overdose are similar to those of other TCAs, with cardiac toxicity (due to inhibition of sodium and calcium channels) generally occurring before the threshold for serotonin syndrome is reached. Due to this risk, TCAs are rarely selected as the first-line treatment for depression.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | ND | ND | ND |

| NET | ND | ND | [9] |

| DAT | >100,000 | Rat | [10] |

| 5-HT1A | >10,000 | Rat | [11] |

| 5-HT2A | ≥1,500 | Rat | [11] |

| 5-HT2C | ND | ND | ND |

| α1 | >10,000 | Rat | [11] |

| α2 | >10,000 | Rat | [11] |

| DA | >10,000 | Bovine | [11] |

| H1 | 23 | Human | [12] |

| H2 | 1,950 | Human | [12] |

| H3 | >100,000 | Human | [12] |

| H4 | >100,000 | Human | [12] |

| mACh | 1,750 | Rat | [11][13] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Dibenzepin acts as a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI), with similar potency to that of imipramine.[9] It is also a potent antihistamine.[11][12] The drug has weak or negligible effects on serotonin and dopamine reuptake.[14][10] Unlike many other TCAs, dibenzepin has no antiadrenergic (α1, α2), antiserotonergic (5-HT1A, 5-HT2A), or antidopaminergic effects and has few or no anticholinergic (mACh) effects.[11][13]

Pharmacokinetics

Therapeutic levels of dibenzepin are approximately 85 to 850 nM.[12] Its plasma protein binding is approximately 80%.[15]

History

Dibenzepin was first introduced, in Switzerland and West Germany, in 1965.[2] It was introduced in France in 1967, in Italy in 1968, in the United Kingdom in 1970, and in Japan in 1975.[2] It was also marketed in a number of other countries, including Portugal and Israel.[2]

Society and culture

References

- Swiss Pharmaceutical Society (2000). Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory (Book with CD-ROM). Boca Raton: Medpharm Scientific Publishers. ISBN 3-88763-075-0.

- Sittig, Marshall (1988). Pharmaceutical manufacturing encyclopedia. Park Ridge, N.J., U.S.A: Noyes Publications. ISBN 0-8155-1144-2.

- Beresewicz M, Bidzińska E, Koszewska I, Puzyński S (1991). "[Results of using tricyclic antidepressive drugs in the treatment of endogenous depression (comparative analysis of 7 drugs)]". Psychiatria Polska (in Polish). 25 (3–4): 13–8. PMID 1687987.

- "Novartis (dibenzepin) - Prescribing Information" (PDF).

- Paloucek, Frank P.; Leikin, Jerrold B. (2007). Poisoning and Toxicology Handbook, Fourth Edition (Poisoning and Toxicology Handbook (Leiken & Paloucek's)). Informa Healthcare. ISBN 1-4200-4479-6.

- Gowardman M, Brown RA (March 1976). "Dibenzepin and amitriptyline in depressive states: comparative double-blind trial". The New Zealand Medical Journal. 83 (560): 194–7. PMID 6928.

- Baron DP, Unger HR, Williams HE, Knight RG (April 1976). "A double blind study of the antidepressants dibenzepin (Noveril) and amitriptyline". The New Zealand Medical Journal. 83 (562): 273–4. PMID 8749.

- Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Barth N, Manns M, Muscholl E (1975). "Arrhythmias and inhibition of noradrenaline uptake caused by tricyclic antidepressants and chlorpromazine on the isolated perfused rabbit heart". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 288 (2–3): 215–31. doi:10.1007/bf00500528. PMID 1161046.

- Hyttel J (1978). "Inhibition of [3H]dopamine accumulation in rat striatal synaptosomes by psychotropic drugs". Biochem. Pharmacol. 27 (7): 1063–8. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(78)90159-4. PMID 656154.

- Closse A, Jaton AL (1984). "Investigation of the influence of lithium upon the down-regulation of serotonin2 receptors in rat frontal cortex induced by long-term treatment with dibenzepin, an antidepressant without appreciable affinity to serotonin2 receptors". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 326 (4): 291–3. doi:10.1007/bf00501432. PMID 6148707.

- Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H₁R, H₂R, H₃R, and H₄R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 385 (2): 145–70. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803.

- Rehavi M, Maayani S, Goldstein L, Assael M, Sokolovsky M (1977). "Antimuscarinic properties of antidepressants: dibenzepin (Noveril)". Psychopharmacology. 54 (1): 35–8. doi:10.1007/bf00426538. PMID 20647.

- Rao ML, Frahnert C, Zagorski O (2002). "Initial serotonin transport into viable platelets and imipramine binding to platelet membranes". J Neural Transm (Vienna). 109 (5–6): 547–56. doi:10.1007/s007020200045. PMID 12111448.

- Josef Aldenhoff (2007). Psychiatrische Therapie. Schattauer Verlag. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-3-7945-2189-0.