Nimetazepam

Nimetazepam (marketed under brand name Erimin and Lavol) is an intermediate-acting hypnotic drug which is a benzodiazepine derivative. It was first synthesized by a team at Hoffmann-La Roche in 1962.[1] It possesses hypnotic, anxiolytic, sedative, and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. Nimetazepam is also an anticonvulsant.[2] It is sold in 5 mg tablets known as Erimin and Lavol. It is generally prescribed for the short-term treatment of severe insomnia in patients who have difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep. The sole global manufacturer of Nimetazepam (Sumitomo Japan) has ceased manufacturing Erimin since early November 2015. Patients being prescribed Erimin are being switched to Lavol and other hypnotics, e.g. estazolam, nitrazepam, flunitrazepam, etc.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Erimin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 95% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 14–30 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.302 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

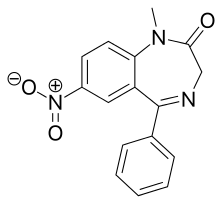

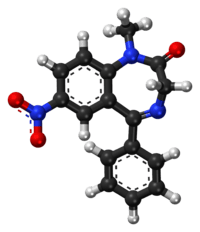

| Formula | C16H13N3O3 |

| Molar mass | 295.3 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Pharmacokinetics

Taken orally, Nimetazepam has very good bioavailability with nearly 100% being absorbed from the gut. It is among the most rapidly absorbed and quickest acting oral benzodiazepines, and hypnotic effects are typically felt within 15–30 minutes after oral ingestion. The blood level decline of the parent drug was biphasic with the short half-life ranging from 0.5–0.7 hours and the terminal half-life from 8 to 26.5 hours (mean 17.25 hours). It is the N-methylated analogue of nitrazepam (Mogadon, Alodorm), to which it is partially metabolized. nitrazepam has a long elimination half-life, so effects of repeated dosage tend to be cumulative.

Recreational use

There is a risk of misuse and dependence in both patients and non-medical users of Nimetazepam. The pharmacological properties of Nimetazepam such as high affinity binding, high potency, being short to intermediate – acting and having a rapid onset of action increase the abuse potential of Nimetazepam. The physical dependence and withdrawal syndrome of Nimetazepam also adds to the addictive nature of Nimetazepam.

Nimetazepam has a particular reputation in South East Asia for recreational use, at around USD 7 per tab, and is particularly popular among persons addicted to amphetamines or opioids.[3][4] Stimulant addicts do not have healthy coping mechanisms due to the nature of addiction, causing insomnia, depression and exhaustion. In addition, Nimetazepam has an anti-depressant and muscle relaxant effect.[5] Nimetazepam also has withdrawal suppression effect and lower drug seeking versus nitrazepam in rhesus monkey (Macaca Mulatta).[6] which might help stimulant addicts to overcome withdrawal symptoms.

Drug misuse

Nimetazepam has a reputation for being particularly subject to abuse (known as 'Happy 5', sold as an ecstasy replacement without a hangover). Although is still a significant drug of abuse in some Asian countries such as Japan and Malaysia, Nimetazepam is subject to legal restrictions in Malaysia, and due to its scarcity, many tablets sold on the black market are in fact counterfeits containing other benzodiazepines such as diazepam or nitrazepam instead.[7][8][9]

Legal status

In United State of America, Nimetazepam is categorized Schedule IV FDA and DEA.

Nimetazepam is currently a Schedule IV drug under the international Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971.[10]

In Singapore, Nimetazepam is a physician prescribed drug, and is regulated under the Misuse of Drugs Act.[11] The illegal possession or consumption of Nimetazepam is punishable by up to 10 years of imprisonment, a fine of 20,000 Singapore dollars, or both illegally. Importing or exporting nimetazepam is punishable by up to 20 years of imprisonment and/or caning.

In Hong Kong, Nimetazepam is regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. Nimetazepam can only be used legally by health professionals and for university research purposes. The substance can be given by pharmacists under a prescription. Anyone who supplies the substance without prescription can be fined $10000 (HKD). The penalty for trafficking or manufacturing the substance is a $5,000,000 (HKD) fine and life imprisonment. Possession of the substance for consumption without license from the Department of Health is illegal with a $1,000,000 (HKD) fine and/or 7 years of jail time.[12]

Similarly in Taiwan and Indonesia Nimetazepam is also regulated as a controlled prescribed substance.

In Victoria Australia, nimetazepam is regulated under Schedule 11 of "Drugs, Poisons and Controlled substances act 1981". It is deemed to fall under the category of "7-NITRO-1,4-BENZODIAZEPINES not included elsewhere in this Part". .[13]

Toxicity

In a rat study Nimetazepam showed greater damage to the fetus, as did nitrazepam when compared against other benzodiazepines, all at a dosage of 100 mg/kg. Diazepam however showed relatively weak fetal toxicities.[14] The same fetotoxicity of nitrazepam could not be observed in mice and is likely due to the particular metabolism of the drug in the rat.[15]

In a rat study nimetazepam showed slight enlargement of the liver and adrenals and atrophy of the testes and ovaries were found in high dose groups of both drugs at the 4th and 12th week, however, in histopathological examination, there were no change in the liver, adrenals and ovaries. Degenerative changes of seminiferous epithelium in the testes were observed, but these atrophic change returned to normal by withdrawal of the drugs for 12 weeks.[16]

See also

- Benzodiazepines

- Flunitrazepam — fluorinated derivative

- Nifoxipam — fluorinated 3-hydroxylated desmethyl derivative

- Nitrazepam — desmethyl derivative

- Temazepam

References

- US patent 3109843, Reeder, E. ; Sternbach, L. H., "Process for preparing 5-phenyl-1,2-dihydro-3H-1,4-benzodiazepines", issued 1963-11-05, assigned to Hoffmann-La Roche

- Fukinaga, M.; Ishizawa, K.; Kamei, C. (1998). "Anticonvulsant properties of 1,4-benzodiazepine derivatives in amygdaloid-kindled seizures and their chemical structure-related anticonvulsant action". Pharmacology. 57 (5): 233–241. doi:10.1159/000028247. PMID 9742288.

- Chong, Y. K.; Kaprawi, M. M.; Chan, K. B. (2004). "The Quantitation of Nimetazepam in Erimin-5 Tablets and Powders by Reverse-Phase HPLC". Microgram Journal. 2 (1–4): 27–33.

- Devaney, M.; Reid, G.; Baldwin, S. (2005). "Situational analysis of illicit drug issues and responses in the Asia-Pacific region" (pdf). ANCD Research Paper 12. Canberra: Australian National Council on Drugs.

- Yamamoto, H.; Kitagawa, S.; Sakai, S. (1972). "Pharmacological Studies on 1-Methyl-7-nitro-5-phenyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one (Nimetazepam)". Pharmacology.

- Yanagita, T.; Takahashi, S.; Oinuma, N. "Drug Dependence Liability of nimetazepam evaluated in the Rhesus Monkey". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Fahmi Lim Abdullah, A.; Abraham, A. A.; Sulaiman, M.; Kunalan, V. (2012). "Forensic Drug Profiling of Erimin-5 Using TLC and GC-MS". Malaysian Journal of Forensic Sciences. 3 (1): 12–15.

- Binti Abdul Rahim, Rusdiyah. "Profiling of Illicit Erimin 5 Tablet Seized in Malaysia". A Research Project Report Submitted To The Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya.

- "Erimin 5 Tablets In Singapore". The Centre for Forensic Science, HSA, Singapore. 2006.

- "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (pdf). Green List Annex to the annual statistical report on psychotropic substances (form P) (23rd ed.). International Narcotics Control Board. August 2003. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "Misuse of drugs act, chapter 185".

- "Bilingual Laws Information System". The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China.

- "Victorian Legislation and Parliamentary Documents". The State Government Victoria.

- Saito, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Takeno, S.; Sakai, T. (1984). "Fetal toxicity of benzodiazepines in rats". Research communications in chemical pathology and pharmacology. 46 (3): 437–447. PMID 6151222.

- Takeno, S.; Hirano, Y.; Kitamura, A.; Sakai, T. (1993). "Comparative Developmental Toxicity and Metabolism of Nitrazepam in Rats and Mice". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 121 (2): 233–238. doi:10.1006/taap.1993.1150. PMID 8346540.

- Yamamoto, T.; Kato, T.; Wada, H.; Kerata, Y. (1972). "Chronic Toxicity of 1-Methyl-7-Nitro-5-phenyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one (Nimetazepam)in Rats". Chronic Toxicity.