Diclazepam

Diclazepam (Ro5-3448), also known as chlorodiazepam and 2'-chloro-diazepam, is a benzodiazepine and functional analog of diazepam. It was first synthesized by Leo Sternbach and his team at Hoffman-La Roche in 1960.[2] It is not currently approved for use as a medication, but rather sold as an unscheduled substance.[3][4][5] Efficacy and safety have not been tested in humans.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, sublingual |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ? |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | ~42 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

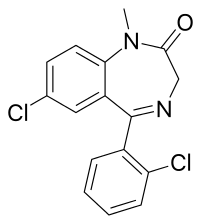

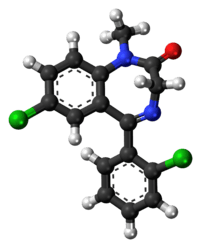

| Formula | C16H12Cl2N2O |

| Molar mass | 319.185 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

In animal models, its effects are similar to diazepam, possessing long-acting anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, sedative, skeletal muscle relaxant, and amnestic properties.

Metabolism

Metabolism of this compound has been assessed,[1] revealing diclazepam has an approximate elimination half-life of 42 hours and undergoes N-demethylation to delorazepam, which can be detected in urine for 6 days following administration of the parent compound.[6] Other metabolites detected were lorazepam and lormetazepam which were detectable in urine for 19 and 11 days, respectively, indicating hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 enzymes occurring concurrently with N-demethylation.

Legal status

United Kingdom

In the UK, diclazepam has been classified as a Class C drug by the May 2017 amendment to The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 along with several other benzodiazepine drugs.[7]

See also

- Diazepam

- Difludiazepam

- Delorazepam (Nordiclazepam)

- Lorazepam

- Phenazepam

- Ro5-4864 (4'-Chlorodiazepam)

References

- Moosmann B, Bisel P, Auwärter V (July–August 2014). "Characterization of the designer benzodiazepine diclazepam and preliminary data on its metabolism and pharmacokinetics". Drug Testing and Analysis. 6 (7–8): 757–63. doi:10.1002/dta.1628. PMID 24604775.

- US 3136815, "Amino substituted benzophenone oximes and derivatives thereof"

- Madeleine Pettersson Bergstrand; Anders Helander; Therese Hansson; Olof Beck (2016). "Detectability of designer benzodiazepines in CEDIA, EMIT II Plus, HEIA, and KIMS II immunochemical screening assays". Drug Testing and Analysis. 9 (4): 640–645. doi:10.1002/dta.2003. PMID 27366870.

- Høiseth, Gudrun; Tuv, Silja Skogstad; Karinen, Ritva (2016). "Blood concentrations of new designer benzodiazepines in forensic cases". Forensic Science International. 268: 35–38. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.09.006. PMID 27685473.

- Manchester, Kieran R.; Maskell, Peter D.; Waters, Laura (2018). "Experimental versus theoretical log D7.4, pKa and plasma protein binding values for benzodiazepines appearing as new psychoactive substances". Drug Testing and Analysis. 10 (8): 1258–1269. doi:10.1002/dta.2387. ISSN 1942-7611. PMID 29582576.

- Bareggi SR, Truci G, Leva S, Zecca L, Pirola R, Smirne S (1988). "Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of intravenous and oral chlordesmethyldiazepam in humans". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 34 (1): 109–112. doi:10.1007/bf01061430. PMID 2896126.

- "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2017".