Triazolam

Triazolam (original brand name Halcion) is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant tranquilizer in the triazolobenzodiazepine class.[2] It possesses pharmacological properties similar to those of other benzodiazepines, but it is generally only used as a sedative to treat severe insomnia.[3] In addition to the hypnotic properties, triazolam's amnesic, anxiolytic, sedative, anticonvulsant, and muscle relaxant properties are pronounced, as well.[4] Due to its short half-life, triazolam is not effective for patients who experience frequent awakenings or early wakening.[5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Halcion |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684004 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 44% (oral route), 53% (sublingual), 98% (intranasal) [[1]] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5–5.5 hours |

| Duration of action | 3-5 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.044.811 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

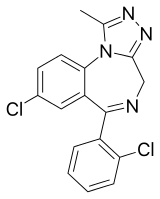

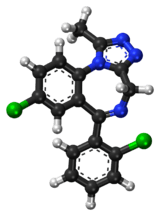

| Formula | C17H12Cl2N4 |

| Molar mass | 343.21 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Triazolam was initially patented in 1970 and went on sale in the United States in 1982.[6]

Medical uses

Triazolam is usually used for short-term treatment of acute insomnia and circadian rhythm sleep disorders, including jet lag. It is an ideal benzodiazepine for this use because of its fast onset of action and short half-life. It puts a person to sleep for about 1.5 hours, allowing its user to avoid morning drowsiness. Triazolam is also sometimes used as an adjuvant in medical procedures requiring anesthesia[3] or to reduce anxiety during brief events, such as MRI scans and nonsurgical dental procedures. Triazolam is ineffective in maintaining sleep, however, due to its short half-life, with quazepam showing superiority.[7]

Triazolam is frequently prescribed as a sleep aid for passengers travelling on short- to medium-duration flights. If this use is contemplated, the user avoiding the consumption of alcoholic beverages is especially important, as is trying a ground-based "rehearsal" of the medication to ensure that the side effects and potency of this medication are understood by the user prior to using it in a relatively more public environment (as disinhibition can be a common side effect, with potentially severe consequences). Triazolam causes anterograde amnesia, which is why so many dentists administer it to patients undergoing even minor dental procedures. This practice is known as sedation dentistry.[8]

Side effects

Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of triazolam include:

- Relatively common (>1% of patients): somnolence, dizziness, feeling of lightness, coordination problems

- Less common (0.9% to 0.5% of patients): euphoria, tachycardia, tiredness, confusional states/memory impairment, cramps/pain, depression, visual disturbances

- Rare (<0.5% of patients): constipation, taste alteration, diarrhea, dry mouth, dermatitis/allergy, dreams/nightmares, insomnia, parasthesia, tinnitus, dysesthesia, weakness, congestion[9]

Triazolam, although a short-acting benzodiazepine, may cause residual impairment into the next day, especially the next morning. A meta-analysis demonstrated that residual "hangover" effects after nighttime administration of triazolam such as sleepiness, psychomotor impairment, and diminished cognitive functions may persist into the next day, which may impair the ability of users to drive safely and increase risks of falls and hip fractures.[10] Confusion and amnesia have been reported.[11]

A 2009 meta-analysis found a 44% higher rate of mild infections, such as pharyngitis or sinusitis, in people taking triazolam or other hypnotic drugs compared to those taking a placebo.[12]

Tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal

A review of the literature found that long-term use of benzodiazepines, including triazolam, is associated with drug tolerance, drug dependence, rebound insomnia, and CNS-related adverse effects. Benzodiazepine hypnotics should be used at their lowest possible dose and for a short period of time. Nonpharmacological treatment options were found to yield sustained improvements in sleep quality.[13] A worsening of insomnia (rebound insomnia) compared to baseline may occur after discontinuation of triazolam, even following short-term, single-dose therapy.[14]

Other withdrawal symptoms can range from mild unpleasant feelings to a major withdrawal syndrome, including stomach cramps, vomiting, muscle cramps, sweating, tremor, and in rare cases, convulsions.[15]

Contraindications

Benzodiazepines require special precautions if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, in alcoholics, or in other drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[16] Triazolam belongs to the Pregnancy Category X of the FDA.[17] It is known to have the potential to cause birth defects.

Elderly

Triazolam, similar to other benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines, causes impairments in body balance and standing steadiness in individuals who wake up at night or the next morning. Falls and hip fractures are frequently reported. The combination with alcohol increases these impairments. Partial, but incomplete tolerance develops to these impairments.[18] Daytime withdrawal effects can occur.[19]

An extensive review of the medical literature regarding the management of insomnia and the elderly found considerable evidence of the effectiveness and durability of nondrug treatments for insomnia in adults of all ages and that these interventions are underused. Compared with the benzodiazepines including triazolam, the nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics appeared to offer few, if any, significant clinical advantages in efficacy or tolerability in elderly persons. Newer agents with novel mechanisms of action and improved safety profiles, such as the melatonin agonists, hold promise for the management of chronic insomnia in elderly people. Long-term use of sedative-hypnotics for insomnia lacks an evidence base and has traditionally been discouraged for reasons that include concerns about such potential adverse drug effects as cognitive impairment, anterograde amnesia, daytime sedation, motor incoordination, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and falls.[19] One study found no evidence of sustained hypnotic efficacy throughout the 9 weeks of treatment for triazolam.[19]

In addition, the effectiveness and safety of long-term use of these agents remain to be determined. More research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of treatment and the most appropriate management strategy for elderly persons with chronic insomnia.[20]

Interactions

Ketoconazole and itraconazole have a profound effect on the pharmacokinetics of triazolam, leading to greatly enhanced effects.[21] Anxiety, tremor, and depression have been documented in a case report following administration of nitrazepam and triazolam. Following administration of erythromycin, repetitive hallucinations and abnormal bodily sensations developed. The patient had, however, acute pneumonia and renal failure. Co-administration of benzodiazepine drugs at therapeutic doses with erythromycin may cause serious psychotic symptoms, especially in those with other physical complications.[22] Caffeine reduces the effectiveness of triazolam.[23] Other important interactions include cimetidine, diltiazem, fluconazole, grapefruit juice, isoniazid, itraconazole, nefazodone, rifampicin, ritonavir, and troleandomycin.[24][25] Triazolam should not be administered to patients on Atripla.

Overdose

Symptoms of an overdose[3] include:

- Coma

- Hypoventilation (respiratory depression)

- Somnolence (drowsiness)

- Slurred speech

- Seizures[9]

Death can occur from triazolam overdose, but is more likely to occur in combination with other depressant drugs such as opioids, alcohol, or tricyclic antidepressants.[26]

Pharmacology

The pharmacological effects of triazolam are similar to those of most other benzodiazepines. It does not generate active metabolites.[3] Triazolam is a short-acting benzodiazepine, is lipophilic, and is metabolised hepatically via oxidative pathways. The main pharmacological effects of triazolam are the enhancement of the neurotransmitter GABA at the GABAA receptor.[27] The half-life of triazolam is only 2 hours making it a very short acting benzodiazepine drug.[28] It has anticonvulsant effects on brain function.[29]

History

Its use at low doses has been deemed acceptable by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and several other countries.[3]

Society and culture

In literature and music

In Operation Shylock by Philip Roth, the protagonist suffers a postoperative mental breakdown partly attributed to the use of triazolam. The incident is based on a real after-effect of Roth's knee surgery and subsequent triazolam use.

The Orbital song "Halcyon" is named after a brand name for the drug, and is dedicated to the Hartnoll brother’s mother, who was addicted to it for many years.

Recreational use

Triazolam issued nonmedically: recreational use wherein the drug is taken to achieve a high or continued long-term dosing against medical advice.[30]

Legal status

Triazolam is a Schedule IV drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances[31] and the U.S. Controlled Substances Act.

Brandnames

The drug is marketed in English-speaking countries under the brand names Apo-Triazo, Halcion, Hypam, and Trilam. Other (designer) names include 2'-chloroxanax, chloroxanax, triclazolam, and chlorotriazolam.

References

- Lui, CY; Amidon, GL; Goldberg, A (1991). "Intranasal absorption of flurazepam, midazolam, and triazolam in dogs". J Pharm Sci. 80 (12): 1125–9. doi:10.1002/jps.2600801207. PMID 1815070.

- "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- Wishart, David (2006). "Triazolam". DrugBank. Retrieved 2006-03-23.

- Mandrioli R, Mercolini L, Raggi MA (October 2008). "Benzodiazepine metabolism: an analytical perspective". Curr. Drug Metab. 9 (8): 827–44. doi:10.2174/138920008786049258. PMID 18855614. Archived from the original on 2009-03-17.

- Rickels K. (1986). "The clinical use of hypnotics: indications for use and the need for a variety of hypnotics". Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 74 (S332): 132–41. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb08990.x. PMID 2883820.

- Shorter, Edward (2005). "B". A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190292010.

- Mauri MC, Gianetti S, Pugnetti L, Altamura AC (1993). "Quazepam versus triazolam in patients with sleep disorders: a double-blind study". Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 13 (3): 173–7. PMID 7901174.

- "Comparison of Triazolam and Zaleplon for Sedation of Dental Patients | Dentistry Today".

- "HALCION-triazolam tablet Pharmacia and Upjohn Company LLC" (PDF). www.pfizer.com. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- Vermeeren A. (2004). "Residual effects of hypnotics: epidemiology and clinical implications". CNS Drugs. 18 (5): 297–328. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003. PMID 15089115.

- Lieberherr, S; Scollo-Lavizzari, G; Battegay, R (1991). "Confusional states following administration of short-acting benzodiazepines (midazolam/triazolam)". Schweizerische Rundschau für Medizin Praxis. 80 (24): 673–5. PMID 2068441.

- Joya, FL; Kripke, DF; Loving, RT; Dawson, A; Kline, LE (2009). "Meta-Analyses of Hypnotics and Infections: Eszopiclone, Ramelteon, Zaleplon, and Zolpidem". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 5 (4): 377–383. PMC 2725260. PMID 19968019.

- Kirkwood CK (1999). "Management of insomnia". J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 39 (5): 688–96, quiz 713–4. doi:10.1016/S1086-5802(15)30354-5. PMID 10533351.

- Kales A; Scharf MB; Kales JD; Soldatos CR. (1979-04-20). "Rebound insomnia. A potential hazard following withdrawal of certain benzodiazepines". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 241 (16): 1692–5. doi:10.1001/jama.241.16.1692. PMID 430730.

- "www.accessdata.fda.gov" (PDF).

- Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, AA.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, PM.; Eschalier, A. (Nov 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Ann Pharm Fr. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- Mets, MA.; Volkerts, ER.; Olivier, B.; Verster, JC. (Feb 2010). "Effect of hypnotic drugs on body balance and standing steadiness". Sleep Med Rev. 14 (4): 259–67. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.008. PMID 20171127.

- Bayer, A.J.; Bayer EM; Pathy MSJ; Stoker MJ. (1986). "A Double-Blind Controlled Study of Chlormethiazole and Triazolam in the Elderly". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 329 (suppl 329): 104–111. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb10544.x. PMID 3529832.

- Bain KT (June 2006). "Management of chronic insomnia in elderly persons". Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 4 (2): 168–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.006. PMID 16860264.

- Varhe A, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ (December 1994). "Oral triazolam is potentially hazardous to patients receiving systemic antimycotics ketoconazole or itraconazole". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 56 (6 Pt 1): 601–7. doi:10.1038/clpt.1994.184. PMID 7995001.

- Tokinaga N; Kondo T; Kaneko S; Otani K; Mihara K; Morita S. (December 1996). "Hallucinations after a therapeutic dose of benzodiazepine hypnotics with co-administration of erythromycin". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 50 (6): 337–9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.1996.tb00577.x. PMID 9014234.

- Mattila, Me; Mattila, Mj; Nuotto, E (April 1992). "Caffeine moderately antagonizes the effects of triazolam and zopiclone on the psychomotor performance of healthy subjects". Pharmacology & Toxicology. 70 (4): 286–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1992.tb00473.x. ISSN 0901-9928. PMID 1351673.

- Wang JS, DeVane CL (2003). "Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions of the sedative hypnotics" (PDF). Psychopharmacol Bull. 37 (1): 10–29. doi:10.1007/BF01990373. PMID 14561946. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-09.

- Arayne, MS.; Sultana, N.; Bibi, Z. (Oct 2005). "Grape fruit juice-drug interactions". Pak J Pharm Sci. 18 (4): 45–57. PMID 16380358.

- Kudo K, Imamura T, Jitsufuchi N, Zhang XX, Tokunaga H, Nagata T (April 1997). "Death attributed to the toxic interaction of triazolam, amitriptyline and other psychotropic drugs". Forensic Sci. Int. 86 (1–2): 35–41. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(97)02110-5. PMID 9153780.

- Oelschläger H. (1989-07-04). "Chemical and pharmacologic aspects of benzodiazepines". Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 78 (27–28): 766–72. PMID 2570451.

- Professor heather Ashton (April 2007). "Benzodiazepine equivalency table". Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- Chweh AY; Swinyard EA; Wolf HH; Kupferberg HJ (February 25, 1985). "Effect of GABA agonists on the neurotoxicity and anticonvulsant activity of benzodiazepines". Life Sci. 36 (8): 737–44. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(85)90193-6. PMID 2983169.

- Griffiths RR, Johnson MW (2005). "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 Suppl 9: 31–41. PMID 16336040.

- "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). Green list. International Narcotics Control Board. Retrieved 2006-03-23.

External links

- PubPK - Triazolam Pharmacokinetics

- Medlineplus.org - Triazolam

- Rx-List.com - Triazolam

- Inchem.org - Triazolam

- MentalHealth.com - Triazolam

- Halcion controversy - Newsweek August 19, 1991 - Sweet Dreams or Nightmare?

- http://www.sussex.ac.uk/sociology/%5B%5D