Loprazolam

Loprazolam (triazulenone) marketed under many brand names is a benzodiazepine medication. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, sedative and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. It is licensed and marketed for the short-term treatment of moderately-severe insomnia.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dormonoct, Havlane, Sonin, Somnovit, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 6–12 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

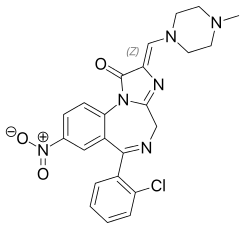

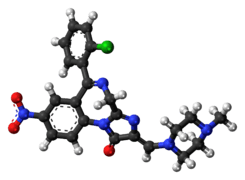

| Formula | C23H21ClN6O3 |

| Molar mass | 464.904 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

It was patented in 1975 and came into medical use in 1983.[1]

Medical uses

Insomnia can be described as a difficulty falling asleep, frequent awakening, early awakenings or a combination of each. Loprazolam is a short-acting benzodiazepine and is sometimes used in patients who have difficulty in maintaining sleep or have difficulty falling asleep. Hypnotics should only be used on a short-term basis or in those with chronic insomnia on an occasional basis.[2]

Dose

The dose of loprazolam for insomnia is usually 1 mg but can be increased to 2 mg if necessary. In the elderly a lower dose is recommended due to more pronounced effects and a significant impairment of standing up to 11 hours after dosing of 1 mg of loprazolam. The half-life is much more prolonged in the elderly than in younger patients. A half-life of 19.8 hours has been reported in elderly patients.[3] Patients and prescribing physicians should, however, bear in mind that higher doses of loprazolam may impair long-term memory functions.[4]

Side effects

Side effects of loprazolam are generally the same as for other benzodiazepines such as diazepam.[5] The most significant difference in side effects of loprazolam and diazepam is it is less prone to day time sedation as the half-life of loprazolam is considered to be intermediate whereas diazepam has a very long half-life. The side effects of loprazolam are the following:

- drowsiness

- paradoxical increase in aggression

- lightheadedness

- confusion

- muscle weakness

- ataxia (particularly in the elderly)

- amnesia

- headache

- vertigo

- hypotension

- salivation changes

- gastro-intestinal disturbances

- visual disturbances

- dysarthria

- tremor

- changes in libido

- incontinence

- urinary retention

- blood disorders and jaundice

- skin reactions

- dependence and withdrawal reactions

Residual 'hangover' effects after nighttime administration of loprazolam such as sleepiness, impaired psychomotor and cognitive functions may persist into the next day which may increase risks of falls and hip fractures.[6]

Tolerance, dependence and withdrawal

Loprazolam, like all other benzodiazepines, is recommended only for the short-term management of insomnia in the UK, owing to the risk of serious adverse effects such as tolerance, dependence and withdrawal, as well as adverse effects on mood and cognition. Benzodiazepines can become less effective over time, and patients can develop increasing physical and psychological adverse effects, e.g., agorophobia, gastrointestinal complaints, and peripheral nerve abnormalities such as burning and tingling sensations.[7][8]

Loprazolam has a low risk of physical dependence and withdrawal if it is used for less than 4 weeks or very occasionally. However, one placebo-controlled study comparing 3 weeks of treatment for insomnia with either loprazolam or triazolam showed rebound anxiety and insomnia occurring 3 days after discontinuing loprazolam therapy, whereas with triazolam the rebound anxiety and insomnia was seen the next day. The differences between the two are likely due to the differing elimination half-lives of the two drugs.[9][10] These results would suggest that loprazolam and possibly other benzodiazepines should be prescribed for 1–2 weeks rather than 2–4 weeks to reduce the risk of physical dependence, withdrawal, and rebound phenomenon.

- Withdrawal symptoms

Slow reduction of the dosage over a period of months at a rate that the individual can tolerate greatly minimizes the severity of the withdrawal symptoms. Individuals who are benzodiazepine dependent often cross to an equivalent dose of diazepam to taper gradually, as diazepam has a longer half-life and small dose reductions can be achieved more easily.[11][12]

- anxiety and panic attacks

- sweating

- nightmares

- insomnia

- headache

- tremor

- nausea and vomiting

- feelings of unreality

- abnormal sensation of movement

- hypersensitivity to stimuli

- hyperventilation

- flushing

- sweating

- palpitations

- dimensional distortions of rooms and television pictures

- paranoid thoughts and feelings of persecution

- depersonalization

- fears of going mad

- heightened perception of taste, smell, sound, and light; photophobia

- agoraphobia

- clinical depression

- poor memory and concentration

- aggression

- excitability

- Somatic Symptoms

- numbness

- altered sensations of the skin

- pain

- stiffness

- weakness in the neck, head, jaw, and limbs

- muscle fasciculation, ranging from twitches to jerks, affecting the legs or shoulders

- ataxia

- paraesthesia

- influenza-like symptoms

- blurred double vision

- menorrhagia

- loss of or dramatic gain in appetite

- thirst with polyuria

- urinary incontinence

- dysphagia

- abdominal pain

- diarrhoea

- constipation

Major complications can occur after abrupt or rapid withdrawal, especially from high doses, producing symptoms such as:

- psychosis

- confusion

- visual and auditory hallucinations

- delusions

- epileptic seizures (which may be fatal)

- suicidal thoughts or actions

- abnormal, often severe, drug seeking behavior

It has been estimated that between 30% and 50% of long-term users of benzodiazepines will experience withdrawal symptoms.[13] However, up to 90% of patients withdrawing from benzodiazepines experienced withdrawal symptoms in one study, but the rate of taper was very fast at 25% of dose per week.[14] Withdrawal symptoms tend to last between 3 weeks to 3 months, although 10–15% of people may experience a protracted benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome with symptoms persisting and gradually declining over a period of many months and occasionally several years.[15]

Contraindications and special caution

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, alcohol or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[16] Loprazolam, similar to other benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drugs causes impairments in body balance and standing steadiness in individuals who wake up at night or the next morning. Falls and hip fractures are frequently reported. The combination with alcohol increases these impairments. Partial, but incomplete tolerance develops to these impairments.[17]

Mechanism of action

Loprazolam is a benzodiazepine, which acts via positively modulating the GABAA receptor complex via a binding to the benzodiazepine receptor which is situated on alpha subunit containing GABAA receptors. This action enhances the effect of the neurotransmitter GABA on the GABAA receptor complex by increasing the opening frequency of the chloride ion channel. This action allows more chloride ions to enter the neuron which in turn produces such effects as; muscle relaxation, anxiolytic, hypnotic, amnesic and anticonvulsant action. These properties can be used for therapeutic benefit in clinical practice. These properties are also sometimes used for recreational purposes in the form of drug abuse of benzodiazepines where high doses are used to achieve intoxication and or sedation.[18][19]

Pharmacokinetics

After oral administration of loprazolam on an empty stomach, it takes 2 hours for serum concentration levels to peak, significantly longer than other benzodiazepine hypnotics. This delay brings into question the benefit of loprazolam for the treatment of insomnia when compared to other hypnotics (particularly when the major complaint is difficulty falling asleep instead of difficulty maintaining sleep for the entire night), although some studies show that loprazolam may induce sleep within half an hour, indicating rapid penetration into the brain. The peak plasma delay of loprazolam, therefore, may not be relevant to loprazolam's efficacy as a hypnotic. If taken after a meal it can take even longer for loprazolam plasma levels to peak and peak levels may be lower than normal. Loprazolam significantly alters electrical activity in the brain as measured by EEG, with these changes becoming more pronounced as the dose increases. Roughly half of each dose is metabolized in humans to produce an active metabolite with similar potency to loprazolam, the other half is excreted unchanged. The half-life of the active metabolite is about the same as the parent compound loprazolam.[20]

See also

References

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 539. ISBN 9783527607495.

- Rickels K. (1986). "The clinical use of hypnotics: indications for use and the need for a variety of hypnotics". Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 74 (S332): 132–41. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb08990.x. PMID 2883820.

- Swift CG; Swift MR; Ankier SI; Pidgen A; Robinson J. (1985). "Single dose pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral loprazolam in the elderly". Biochemical Medicine. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 13 (2): 117–26. doi:10.1016/0006-2944(75)90147-7. PMID 1.

- Bareggi SR; Ferini-Strambi L; Pirola R; Franceschi M; Smirne S. (1991). "Effects of loprazolam on cognitive functions". Biochemical Medicine. Psychopharmacology. 13 (2): 117–26. doi:10.1016/0006-2944(75)90147-7. PMID 1.

- British National Formulary Benzodiazepines Information

- Vermeeren A. (2004). "Residual effects of hypnotics: epidemiology and clinical implications". CNS Drugs. 18 (5): 297–328. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003. PMID 15089115.

- Committee on Safety of Medicines (1988). "BENZODIAZEPINES, DEPENDENCE AND WITHDRAWAL SYMPTOMS". Medicines Control Agency UK Government. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- Professor C Heather Ashton (1987). "Benzodiazepine Withdrawal: Outcome in 50 Patients". benzo. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- Morgan K, Oswald I (1982). "Anxiety caused by a short-life hypnotic". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.). 284 (6320): 942. doi:10.1136/bmj.284.6320.942. PMC 1496517. PMID 6121606. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- Morgan K, Adam K, Oswald I (1984). "Effect of loprazolam and of triazolam on psychological functions". Psychopharmacology. 82 (4): 386–388. doi:10.1007/BF00427691. PMID 1.

- McConnell JG (2007). "The Clinicopharmacotherapeutics of Benzodiazepine and Z drug dose Tapering Using Diazepam". BCNC. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- (Roche Products (UK) Ltd 1990) Benzodiazepines and Your Patients: A Management Programme

- Schweizer E, Rickels K, Case WG, Greenblatt DJ (1990). "Long-term therapeutic use of benzodiazepines. II. Effects of gradual taper". Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 47 (10): 908–915. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810220024003. PMID 1.

- Ashton CH (2002). "BENZODIAZEPINES: How They Work and How to Withdraw". benzo org uk. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, AA.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, PM.; Eschalier, A. (Nov 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Ann Pharm Fr. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- Mets, MA.; Volkerts, ER.; Olivier, B.; Verster, JC. (Feb 2010). "Effect of hypnotic drugs on body balance and standing steadiness". Sleep Med Rev. 14 (4): 259–67. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.008. PMID 20171127.

- Bateson AN (2002). "Basic pharmacologic mechanisms involved in benzodiazepine tolerance and withdrawal". Current Pharmaceutical Design. ingentaconnect. 8 (1): 5–21. doi:10.2174/1381612023396681. PMID 11812247.

- Professor C Heather Ashton (2002). "BENZODIAZEPINE ABUSE". Harwood Academic. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- Mamelak M, Bunting P, Galin H, Price V, Csima A, Young T, Klein D, Pelchat JR (1988). "Serum and quantitative electroencephalographic pharmacokinetics of loprazolam in the elderly". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 28 (4): 376–83. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03162.x. PMID 3392236.