Phenazepam

Phenazepam (also known in Russia as bromdihydrochlorphenylbenzodiazepine) is a benzodiazepine drug, which was developed in the Soviet Union in 1975,[3] and now produced in Russia and some CIS countries. Phenazepam is used in the treatment of various psychiatric and neurological disorders. It can be used as a premedication before surgery as it augments the effects of anesthetics and reduces anxiety. Recently, phenazepam has gained popularity as a recreational drug; misuse has been reported in the United Kingdom,[4] Finland,[5] Sweden,[6] and the United States.[7]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | see below |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral, IM, IV |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 16,7% (rat)[1] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic — aromatic oxidation and C3-hydroxylation[2] |

| Onset of action | 1.5–4 hours |

| Elimination half-life | 6–18 hours (active metabolite up to 60 hours) |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.207.405 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

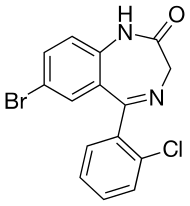

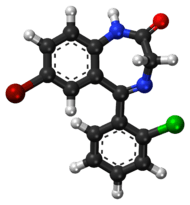

| Formula | C15H10BrClN2O |

| Molar mass | 349.6 g·mol−1 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Indications

- Neurosis, neurosis-like, psychopathic (personality disorder), psychopathic-like and other conditions accompanied by fear, anxiety, increased irritability, and emotional lability

- Brief reactive psychosis and hypochondriasis-senestopathic syndrome

- Vegetative dysfunction and vegetative lability

- Insomnia

- Alcohol withdrawal syndrome

- Temporal lobe epilepsy and myoclonic epilepsy (used only occasionally as better options exist)

- Hyperkinesia and tics

- Muscle spasticity[8]

Usually, a course of treatment with phenazepam should not normally exceed 2 weeks (in some cases therapy may be prolonged for up to 2 months) due to the risk of drug abuse and dependence. To prevent withdrawal syndrome, it is necessary to reduce the dose gradually.[8]

Side effects

Side effects include hiccups, dizziness, loss of coordination and drowsiness, along with anterograde amnesia which can be quite pronounced at high doses.[9] As with other benzodiazepines, in case of abrupt discontinuation following prolonged use, severe withdrawal symptoms may occur including restlessness, anxiety, insomnia, seizures, convulsions and death, though because of its long half-life, these withdrawal symptoms may take two or more days to manifest.

Contraindications and special caution

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, alcohol or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[10]

Phenazepam should not be taken with alcohol or any other CNS depressants. Phenazepam should not be used therapeutically for periods of longer than one month including tapering on and off the drug as recommended for any benzodiazepine in the British national formulary. Some patients may require longer term treatment.

Phenazepam was found to be a component in some herbal incense mixtures in Australia & New Zealand in 2011, namely "Kronic". The particular product variety was withdrawn shortly from the market after and replaced with a new formulation.[11]

Synthesis

First, 2-(o-chlorobenzoylamino)-5-bromo-2-chlorobenzophenone is prepared by acylation of p-bromoaniline with o-chlorobenzoic acid acyl chloride in the presence of a zinc chloride catalyst. This is hydrolysed with aqueous sulfuric acid to yield 2-amino-5-bromo-2'-chlorobenzophenone, which is then acylated with hydrochloride of aminoacetic acid acyl chloride in chloroform to form 2-(aminomethylkarbonylamino)-5-bromo-2-chlorobenzophenone hydrochloride, which is converted to a base with aqueous ammonia and then thermally cyclized to bromodihydrochlorophenylbenzodiazepine (phenazepam).

Hydrochloride of aminoacetic acid acyl chloride is prepared by chemical treating glycine with phosphorus pentachloride (PCI₅) in chloroform.[12]

.png)

This method of Phenazepam synthesis was developed in the 1970s at the Physico-Chemical Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR.[12]

Detection in biological fluids

Phenazepam may be measured in blood or plasma by chromatographic methods. Blood phenazepam concentrations are typically less than 30 μg/L during therapeutic usage, but have frequently been in the 100–600 μg/L range in automotive vehicle operators arrested for impaired driving ability.[13]

Legal status

China

As of October 2015, phenazepam is a controlled substance in China.[14]

United States

Under federal United States law, phenazepam is not currently classified as a controlled substance, as the Federal Analog Act only provides for automatic assumed classification of chemicals "substantially similar" to existing Schedule I or Schedule II drugs, whereas all controlled benzodiazepines under the Controlled Substances Act are classified as Schedule IV. Although phenazepam is currently not controlled, sale for human use remains illegal in the United States.[15] Suppliers attempt to circumvent this regulation by placing a "Not for human use" disclaimer on the product's label.

Individual states in the United States often ban these analog drugs by name as they appear. Since 2012, Louisiana has classified phenazepam as a controlled dangerous substance.[16] This ban affects several products, some of which were sold at retail stores under the guise of air freshener or similar, containing phenazepam yet claiming not to be for human use. This legislation was introduced after one such product, branded as "Zannie" and marketed as an air freshener rapidly gained publicity as the subject of numerous media reports, attracting the attention of officials.[17] The ensuing investigation effort, led by Senator Fred Mills and Louisiana Poison Center Director Mark Ryan, positively identified the active ingredient of "Zannie" as phenazepam. According to Ryan, chemical analysis identified the active ingredient as "100 percent phenazepam".[16]

Paul Halverson, director and state health officer for the Arkansas Department of Health, approved an emergency rule to ban the sale and distribution of phenazepam shortly after the Louisiana ban.

United Kingdom

Phenazepam is a class C drug in the UK.[18]

The UK home office banned importation of phenazepam on Friday 22 July 2011[19] while it drafted legislation, released in January 2012[20] to become law at the end of March 2012.[21] The bill was quashed following advice from the ACMD as it included two non-abusable steroids.[22] There was a new discussion about its fate on April 23, 2012, where it was decided that the bill would be rewritten and phenazepam would still be banned.[23]

It was eventually banned on June 13, 2012 as a class C, schedule II drug.[24]

Elsewhere

Phenazepam was classified as a narcotic in Finland in July, 2014.[25]

Phenazepam is considered a narcotic in Norway, as per a March 23, 2010 Health Department addition to the Regular Narcotic List.

In Russia, while the drug is considered a prescription medication (but not a controlled one, as all other benzodiazepines except tofisopam), some pharmacies sell it without prescriptions required.

In Estonia, phenazepam is a Schedule IV substance under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act. Schedule IV is the lowest classification of psychoactive substances in Estonia. It includes prescribable drugs, including other benzodiazepines.

UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs

On 8 March 2016 at its 59th Session, the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) added Phenazepam to relevant schedules of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961.[26]

Trade names

RU:

- «Феназепам« (Phenazepam) tablets 0.5, 1 and 2.5 mg, solution for intramuscular and intravenous injection 1 mg/mL (0.1%)

- «Элзепам» (Elzepam) tablets 0.5 and 1 mg, solution for intramuscular and intravenous injection 1 mg/mL (0.1%)

- «Фензитат» (Phenzitat) tablets 0.5 and 1 mg

- «Фенорелаксан» (Phenorelaxan) tablets 0.5 and 1 mg, solution for intramuscular and intravenous injection 1 mg/mL (0.1%)

- «Транквезипам» (Trankvezipam) tablets 0.5 and 1 mg, solution for intramuscular and intravenous injection 1 mg/mL (0.1%)

- «Фезипам» (Phezipam) tablets 0.5 and 1 mg (not to be confused with «Фезам» (Phezam) which contains cinnarizine/piracetam)

- «Фезанеф» (Phezanef) tablets 1 mg[27]

See also

- Benzodiazepine

- 3-Hydroxyphenazepam—an active metabolite and a designer drug

- Delorazepam—7-chlorinated analog

References

- "Pharmacokinetics of Transdermal therapeutic Systems of Phenazepam and Cytisine in the Experiment (abstract)". DisserCat — Electronic Library of Dissertations (in Russian).

- Golovenko, NIa; Zin'kovskiĭ, VG (1979). "[2-14C-phenazepam metabolism in vitro]". Farmakologiia I Toksikologiia (in Russian). 42 (6): 597–600. PMID 40817.

- "World Health Organization". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- Corkery, J. M.; Schifano, F.; Ghodse, A. H. (2012). "Phenazepam abuse in the UK: An emerging problem causing serious adverse health problems, including death". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 27 (3): 254–61. doi:10.1002/hup.2222. PMID 22407587.

- Kriikku, P.; Wilhelm, L.; Rintatalo, J.; Hurme, J.; Kramer, J.; Ojanperä, I. (2012). "Phenazepam abuse in Finland: Findings from apprehended drivers, post-mortem cases and police confiscations". Forensic Science International. 220 (1–3): 111–117. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.02.006. PMID 22391477.

- Mrozkowska, J.; Vinge, E.; Borna, C. (2009). "Abuse of phenazepam--new phenomenon in Sweden. Benzodiazepine derivative from Russia caused severe intoxication". Lakartidningen. 106 (8): 516–517. PMID 19350785.

- Maskell, P. D.; De Paoli, G.; Nitin Seetohul, L.; Pounder, D. J. (2012). "Phenazepam: The drug that came in from the cold". Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 19 (3): 122–125. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2011.12.014. PMID 22390996.

- "Phenazepam (bromdihydrochlorphenylbenzodiazepine) Tablets. Full Prescribing Information". Russian State register of Medicines (in Russian). Valenta Pharm, JSC. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Stephenson, Jon; David Golz; Mary Jo Brasher (January 2013). "Phenazepam and its effects on driving". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 37 (1): 25–29. doi:10.1093/jat/bks080. PMID 23074215. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, A. A.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, P. -M.; Eschalier, A. (2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: Focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- Couch, R. A. F.; Madhavaram, H. (2012). "Phenazepam and cannabinomimetics sold as herbal highs in New Zealand". Drug Testing and Analysis. 4 (6): 409–414. doi:10.1002/dta.349. PMID 22924168.

- Яхонтов, Л. H.; Глушков, P. Г. (1983). Синтетические лекарственные средства [Synthetic pharmaceutical drugs] (in Russian). Moscow: Медицина (Medicine). pp. 215–216.

- R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 9th edition, Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, CA, 2011, pp. 1320-1321. Archived 2011-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- "关于印发《非药用类麻醉药品和精神药品列管办法》的通知" (in Chinese). China Food and Drug Administration. 27 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- "New York Nurse Sentenced for Selling Unapproved "Party Drug" Phenazepam on the Internet". U.S. Department of Justice. October 10, 2012.

sale for human consumption is prohibited in the United States except for research under strictly regulated terms

- "Bill to Ban Zannie Passes". KSLA 12. 2012-05-21. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- "'Air Freshener' Contains Potentially Deadly Contolled Drug". KTBS. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "PHENAZEPAM". Talk To Frank. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- "Phenazepam / Home Office". UK Home Office. 2012-04-12. Archived from the original on 2012-04-12. Retrieved 2013-02-11.

- "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2012" (PDF). UK Home Office. 2012-01-27. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- "Letter from Lord Henly to the ACMD" (PDF). UK Home Office. 2012-01-27. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- "ACMD letter on further advice on the classification of two steroidal substances - February 2012" (PDF). UK Home Office. 2012-02-14. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- "Draft Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2012". UK Home Office. 2012-04-23. Retrieved 2012-05-04.

- "A Change to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971: control of pipradrol-related compounds and phenazepam". UK Home Office. 7 Jun 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- "Valtioneuvoston asetus huumausaineina pidettävistä aineista, valmisteista ja kasveista annetun valtioneuvoston asetuksen liitteen IV muuttamisesta".

- "State Register of Medicines: Bromdihydrofluorobenzodiazepine. Prescribing Information Lists". Russian State Register of Medicines (http://grls.rosminzdrav.ru/default.aspx) (in Russian). Retrieved 5 December 2015. External link in

|website=(help)