Lamotrigine

Lamotrigine, sold as the brand name Lamictal among others, is an anticonvulsant medication used to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder.[2] For epilepsy, this includes focal seizures, tonic-clonic seizures, and seizures in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.[2] In bipolar disorder, it is used to treat acute episodes of depression and rapid cycling in bipolar type II and to prevent recurrence in bipolar type I.[2]

| |||

| Clinical data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ləˈmoʊtrɪˌdʒiːn/ | ||

| Trade names | Lamictal, others[1] | ||

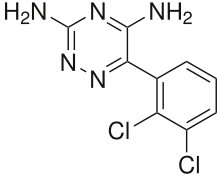

| Other names | BW-430C; BW430C; 3,5-Diamino-6-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-1,2,4-triazine | ||

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph | ||

| MedlinePlus | a695007 | ||

| License data |

| ||

| Pregnancy category | |||

| Routes of administration | By mouth | ||

| ATC code | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Legal status | |||

| Pharmacokinetic data | |||

| Bioavailability | 98% | ||

| Protein binding | 55% | ||

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly UGT1A4-mediated) | ||

| Elimination half-life | 29 hours | ||

| Excretion | Urine (65%), feces (2%) | ||

| Identifiers | |||

IUPAC name

| |||

| CAS Number | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| IUPHAR/BPS | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| UNII | |||

| KEGG | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.074.432 | ||

| Chemical and physical data | |||

| Formula | C9H7Cl2N5 | ||

| Molar mass | 256.091 g/mol g·mol−1 | ||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

SMILES

| |||

InChI

| |||

| | |||

Common side effects include sleepiness, headache, vomiting, trouble with coordination, and rash.[2] Serious side effects include lack of red blood cells, increased risk of suicide, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and allergic reactions.[2] Concerns exist that use during pregnancy or breastfeeding may result in harm.[3] Lamotrigine is a phenyltriazine, making it chemically different from other anticonvulsants.[2] How it works is not exactly clear.[2] It appears to increase the action of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system and decrease voltage-sensitive sodium channels.[2][4]

Lamotrigine was first marketed in the United Kingdom in 1991 and approved for use in the United States in 1994.[2][5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safest medicines needed in a health system.[6] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$3.50 to US$23 per month as of 2015.[7] In the United States, this amount has a wholesale cost of about US$4.60 as of 2019.[8]

Medical uses

Epilepsy

Lamotrigine is considered a first-line drug for primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures (includes simple partial, complex partial, and secondarily generalized seizures such as focal-onset tonic-clonic seizures). It is also used as an alternative or adjuvant medication for partial seizures, such as absence seizure, myoclonic seizure, and atonic seizures.[9][10]

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome

Lamotrigine is one of a small number of FDA-approved therapies for the form of epilepsy known as Lennox–Gastaut syndrome.[11] It reduces the frequency of LGS seizures, and is one of two medications known to decrease the severity of drop attacks.[12] Combination with valproate is common, but this increases the risk of lamotrigine-induced rash, and necessitates reduced dosing due to the interaction of these drugs.[13]

Bipolar disorder

Lamotrigine is approved in the US for maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder.[14][15] While the anticonvulsants carbamazepine and valproate are predominantly antimanics, lamotrigine is most effective for preventing the recurrent depressive episodes of bipolar disorder. The drug seems ineffective in the treatment of current rapid-cycling, acute mania, or acute depression in bipolar disorder; however, it is effective at prevention of or delaying of manic, depressive, or rapid cycling episodes.[16] According to studies in 2007, lamotrigine may treat bipolar depression without triggering mania, hypomania, mixed states, or rapid-cycling.[17]

Therapeutic benefit is less evident when lamotrigine is used to treat a current-mood episode. It has not demonstrated effectiveness in treating acute mania,[18] and there is controversy regarding the drug's effectiveness in treating acute bipolar depression.[19] While the 2002 American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines recommend lamotrigine as a first-line treatment for acute depression in bipolar II disorder,[20] their website notes that the guidelines, being more than five years old, "can no longer be assumed to be current".[21] A paper written in 2008 by Nassir et al. reviewed evidence from trials that were unpublished and not referenced in the 2002 APA guidelines, and it concludes that lamotrigine has "very limited, if any, efficacy in the treatment of acute bipolar depression".[16] A 2008 paper by Calabrese et al. examined much of the same data, and found that in five placebo-controlled studies, lamotrigine did not significantly differ from placebo in the treatment of bipolar depression.[22] However, in a meta-analysis of these studies conducted in 2008, Calabrese found that lamotrigine was effective in individuals with bipolar depression, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 11, or 7 in severe depression.[23]

A 2013 review about lamotrigine concluded that it is recommended in bipolar maintenance when depression is prominent and that more research is needed in regard to its role in the treatment of acute bipolar depression and unipolar depression. Furthermore, no information to recommend its use in other psychiatric disorders was found.[24]

Other uses

Off-label uses include the treatment of peripheral neuropathy, trigeminal neuralgia, cluster headaches, migraines, visual snow, and reducing neuropathic pain,[25][26][27][28] although a systematic review conducted in 2013 concluded that well-designed clinical trials have shown no benefit for lamotrigine in neuropathic pain.[29] Off-label psychiatric usage includes the treatment of treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder,[30] depersonalization disorder,[31] hallucinogen persisting perception disorder,[32] schizoaffective disorder,[33] and borderline personality disorder.[34] It has not been shown to be useful in post-traumatic stress disorder.[35]

Side effects

Lamotrigine prescribing information has a black box warning about life-threatening skin reactions, including Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), DRESS syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).[36] The manufacturer states that nearly all cases appear in the first two to eight weeks of therapy.[36] Patients should seek medical attention for any unexpected skin rash, as its presence is an indication of a possible serious or even deadly side effect of the drug. Not all rashes that occur while taking lamotrigine progress to SJS or TEN. Between 5 and 10% of patients will develop a rash, but only one in a thousand patients will develop a serious rash. Rash and other skin reactions are more common in children, so this medication is often reserved for adults. For patients whose lamotrigine has been stopped after development of a rash, rechallenge with lamotrigine is also a viable option. However, it is not applicable for very serious cases.[37]

The incidence of these eruptions increases in patients who are currently on, or recently discontinued a valproate-type anticonvulsant drug, as these medications interact in such a way that the clearance of both is decreased and the effective dose of lamotrigine is increased.[36]

Side effects such as rash, fever, and fatigue are very serious, as they may indicate incipient SJS, TEN, DRESS syndrome, or aseptic meningitis.[38]

Other side effects include loss of balance or coordination, double vision, crossed eyes, pupil constriction, blurred vision, dizziness and lack of coordination, drowsiness, insomnia, anxiety, vivid dreams or nightmares, dry mouth, mouth ulcers, memory problems, mood changes, itchiness, runny nose, cough, nausea, indigestion, abdominal pain, weight loss, missed or painful menstrual periods, and vaginitis. The side-effects profile varies for different patient populations.[38] Overall adverse effects in treatment are similar between men, women, geriatric, pediatric and racial groups.[39]

Lamotrigine has been associated with a decrease in white blood cell count (leukopenia).[40] Lamotrigine does not prolong QT/QTc in TQT studies in healthy subjects.[41]

In people taking antipsychotics, cases of lamotrigine-precipitated neuroleptic malignant syndrome have been reported.[42][43]

In 2018, the FDA required a new warning for the risk of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. This reaction can occur between days to weeks after starting the treatment.[44]

Women

Women are more likely than men to have side effects.[45] This is the opposite of most other anticonvulsants.

Some evidence shows interactions between lamotrigine and female hormones, which can be of particular concern for women on estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives. Ethinylestradiol, an ingredient of such contraceptives, has been shown to decrease serum levels of lamotrigine.[46] Women starting an estrogen-containing oral contraceptive may need to increase the dosage of lamotrigine to maintain its level of efficacy. Likewise, women may experience an increase in lamotrigine side effects upon discontinuation of birth control pills. This may include the "pill-free" week where lamotrigine serum levels have been shown to increase twofold.[36]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Many studies have found no association between lamotrigine exposure in utero and birth defects, while those that have found an association have found only slight associations with minor malformations such as cleft palates.[47] Review studies have found that overall rates of congenital malformations in infants exposed to lamotrigine in utero are relatively low (1-4%), which is similar to the rate of malformations in the general population.[48][49] It is known that lamotrigine is a weak inhibitor of human dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and other, more powerful, human DHFR inhibitors such as methotrexate are known to be teratogenic.[47]

Lamotrigine is expressed in breast milk; the manufacturer does not recommend breastfeeding during treatment. A frequently updated review of scientific literature rates lamotrigine as L3: moderately safe.[50]

Other types of effects

Lamotrigine binds to melanin-containing tissues such as the iris of the eye. The long-term consequences of this are unknown.[51]

GlaxoSmithKline investigated lamotrigine for the treatment of ADHD with inconclusive results. No detrimental effects on cognitive function were observed; however, the only statistical improvement in core ADHD symptoms was an improvement on a Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test that measures auditory processing speed and calculation ability.[52] Another study reported that lamotrigine might be a safe and effective treatment option for adult ADHD comorbid with bipolar and recurrent depression.[53]

Lamotrigine is known to affect sleep. Studies with small numbers of patients (10-15) reported that lamotrigine increases sleep stability (increases the duration of REM sleep, decreases the number of phase shifts, and decreases the duration of slow-wave sleep),[54] and that there was no effect on vigilance,[55] and daytime somnolence and cognitive function.[56] However, a retrospective study of 109 patients' medical records found that 6.7% of patients experienced an "alerting effect" resulting in intolerable insomnia, for which the treatment had to be discontinued.[57]

Lamotrigine can induce a type of seizure known as a myoclonic jerk, which tends to happen soon after the use of the medication.[58] When used in the treatment of myoclonic epilepsies such as juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, lower doses (and lower plasma levels) are usually needed, as even moderate doses of this drug can induce seizures, including tonic-clonic seizures, which can develop into status epilepticus, which is a medical emergency. It can also cause myoclonic status epilepticus.[39]

In overdose, lamotrigine can cause uncontrolled seizures in most people. Reported results in overdoses involving up to 15 g include increased seizures, coma, and death.[39]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Lamotrigine is a member of the sodium channel blocking class of antiepileptic drugs.[59] This may suppress the release of glutamate and aspartate, two of the dominant excitatory neurotransmitters in the CNS.[60] It is generally accepted to be a member of the sodium channel blocking class of antiepileptic drugs,[61] but it could have additional actions, since it has a broader spectrum of action than other sodium channel antiepileptic drugs such as phenytoin and is effective in the treatment of the depressed phase of bipolar disorder, whereas other sodium channel-blocking antiepileptic drugs are not, possibly on account of its sigma receptor activity. In addition, lamotrigine shares few side effects with other, unrelated anticonvulsants known to inhibit sodium channels, which further emphasises its unique properties.[62]

It is a triazine derivate that inhibits voltage-sensitive sodium channels, leading to stabilization of neuronal membranes. It also blocks L-, N-, and P-type calcium channels and has weak 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor inhibition. These actions are thought to inhibit release of glutamate at cortical projections in the ventral striatum limbic areas,[63] and its neuroprotective and antiglutamatergic effects have been pointed out as promising contributors to its mood stabilizing activity.[64] Observations that lamotrigine reduced γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor-mediated neurotransmission in rat amygdala, suggest that a GABAergic mechanism may also be involved.[65] It appears that lamotrigine does not increase GABA levels in humans.[66]

Lamotrigine does not have pronounced effects on any of the usual neurotransmitter receptors that anticonvulsants affect (adrenergic, dopamine D1 and D2, muscarinic, GABA, histaminergic H1, serotonin 5-HT2, and N-methyl-D-aspartate). Inhibitory effects on 5-HT, norepinephrine, and dopamine transporters are weak.[67] Lamotrigine is a weak inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase,[68] but whether this effect is sufficient to contribute to a mechanism of action or increases risk to the fetus during pregnancy is not known. Early studies of lamotrigine's mechanism of action examined its effects on the release of endogenous amino acids from rat cerebral cortex slices in vitro. As is the case for antiepileptic drugs that act on voltage-dependent sodium channels, lamotrigine thereby inhibits the release of glutamate and aspartate, which is evoked by the sodium-channel activator veratrine, and was less effective in the inhibition of acetylcholine or GABA release. At high concentrations, it had no effect on spontaneous or potassium-evoked amino acid release.[45]

These studies suggested that lamotrigine acts presynaptically on voltage-gated sodium channels to decrease glutamate release. Several electrophysiological studies have investigated the effects of lamotrigine on voltage-dependent sodium channels. For example, lamotrigine blocked sustained repetitive firing in cultured mouse spinal cord neurons in a concentration-dependent manner, at concentrations that are therapeutically relevant in the treatment of human seizures. In cultured hippocampal neurons, lamotrigine reduced sodium currents in a voltage-dependent manner, and at depolarised potentials showed a small frequency-dependent inhibition. These and a variety of other results indicate that the antiepileptic effect of lamotrigine, like those of phenytoin and carbamazepine, is at least in part due to use- and voltage-dependent modulation of fast voltage-dependent sodium currents. However, lamotrigine has a broader clinical spectrum of activity than phenytoin and carbamazepine and is recognised to be protective against generalised absence epilepsy and other generalised epilepsy syndromes, including primary generalised tonic–clonic seizures, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.

The basis for this broader spectrum of activity of lamotrigine is unknown, but could relate to actions of the drug on voltage-activated calcium channels. Lamotrigine blocks T-type calcium channels weakly, if at all. However, it does inhibit native and recombinant high voltage–activated calcium channels (N- and P/Q/R-types) at therapeutic concentrations. Whether this activity on calcium channels accounts for lamotrigine's broader clinical spectrum of activity in comparison with phenytoin and carbamazepine remains to be determined.

It antagonises these receptors with the following IC50 values:[68]

- 5-HT3, IC50=18μM

- σ receptors, IC50=145μM

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine follow first-order kinetics, with a half-life of 29 hours and volume of distribution of 1.36 L/kg.[69] Lamotrigine is rapidly and completely absorbed after oral administration. Its absolute bioavailability is 98% and its plasma Cmax occurs from 1.4 to 4.8 hours. Available data indicate that its bioavailability is not affected by food. Estimate of the mean apparent volume of distribution of lamotrigine following oral administration ranges from 0.9 to 1.3 L/kg. This is independent of dose and is similar following single and multiple doses in both patients with epilepsy and in healthy volunteers.[70]

Lamotrigine is inactivated by glucuronidation in the liver.[71] Lamotrigine is metabolized predominantly by glucuronic acid conjugation. Its major metabolite is an inactive 2-n-glucuronide conjugate.[72]

Lamotrigine has fewer drug interactions than many anticonvulsant drugs, although pharmacokinetic interactions with carbamazepine, phenytoin and other hepatic enzyme inducing medications may shorten half-life.[73] Dose adjustments should be made on clinical response, but monitoring may be of benefit in assessing compliance.[45]

The capacity of available tests to detect potentially adverse consequences of melanin binding is unknown. Clinical trials excluded subtle effects and optimal duration of treatment. There are no specific recommendations for periodic ophthalmological monitoring. Lamotrigine binds to the eye and melanin-containing tissues which can accumulate over time and may cause toxicity. Prescribers should be aware of the possibility of long-term ophthalmologic effects and base treatment on clinical response. Patient compliance should be periodically reassessed with lab and medical testing of liver and kidney function to monitor progress or side effects.[45]

History

- 1991 - Lamotrigine is first used in the United Kingdom as an anticonvulsant medication[74]

- December 1994 — lamotrigine was first approved for use in the United States and, that for the treatment of partial seizures.[75]

- August 1998 — for use as adjunctive treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in pediatric and adult patients, new dosage form: chewable dispersible tablets.

- December 1998 — for use as monotherapy for treatment of partial seizures in adult patients when converting from a single enzyme-inducing anticonvulsant drug.

- January 2003 — for use as adjunctive therapy for partial seizures in pediatric patients as young as two years of age.

- June 2003 — approved for maintenance treatment of Bipolar II disorder; the first such medication since lithium.[14]

- January 2004 — for use as monotherapy for treatment of partial seizures in adult patients when converting from the anti-epileptic drug valproate [including valproic acid (Depakene); sodium valproate (Epilim) and divalproex sodium (Depakote)].

Society and culture

References

- "Lamotrigine". Drugs.com. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Lamotrigine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- "Lamotrigine Use During Pregnancy | Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Lamotrigine". PubChem Open Chemistry Database. US: National Institutes of Health. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- Shorvon SD, Perucca E, Engel J (2015). The Treatment of Epilepsy (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. p. 1321. ISBN 9781118936993.

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (20th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. March 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Single Drug Information". International Medical Products Price Guide. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "NADAC as of 2019-11-27 | Data.Medicaid.gov". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Kasper D (2005). Fauci AS, Braunwald E, et al. (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 16th ed. McGraw-Hill. pp. 3–22. ISBN 9780071466332.

- Tierny LM (2006). McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA (eds.). Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment, 45th ed. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071454100.

- Hancock EC, Cross JH (February 2013). "Treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003277. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003277.pub3. PMID 23450537.

- French JA, Kanner AM, Bautista J, Abou-Khalil B, Browne T, Harden CL, Theodore WH, Bazil C, Stern J, Schachter SC, Bergen D, Hirtz D, Montouris GD, Nespeca M, Gidal B, Marks WJ, Turk WR, Fischer JH, Bourgeois B, Wilner A, Faught RE, Sachdeo RC, Beydoun A, Glauser TA (April 2004). "Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs II: treatment of refractory epilepsy: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee and Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society". Neurology. 62 (8): 1261–73. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000123695.22623.32. PMID 15111660.

- Pellock JM (November 1999). "Managing pediatric epilepsy syndromes with new antiepileptic drugs". Pediatrics. 104 (5 Pt 1): 1106–16. doi:10.1542/peds.104.5.1106. PMID 10545555.

- GlaxoSmithKline, 2003

- GlaxoSmithKline (12 October 2010). "Lamictal (lamotrigine) Label Information" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Nassir Ghaemi S, Shirzadi AA, Filkowski M (2008). "Publication bias and the pharmaceutical industry: the case of lamotrigine in bipolar disorder". Medscape Journal of Medicine. 10 (9): 211. PMC 2580079. PMID 19008973.

- Goldberg JF, Calabrese JR, Saville BR, Frye MA, Ketter TA, Suppes T, Post RM, Goodwin FK (September 2009). "Mood stabilization and destabilization during acute and continuation phase treatment for bipolar I disorder with lamotrigine or placebo". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 70 (9): 1273–80. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.618.5310. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04381. PMID 19689918.

- Goldsmith DR, Wagstaff AJ, Ibbotson T, Perry CM (2003). "Lamotrigine: a review of its use in bipolar disorder". Drugs. 63 (19): 2029–50. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363190-00009. PMID 12962521.

- Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ (May 2013). "Treatment of bipolar disorder". Lancet. 381 (9878): 1672–82. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60857-0. PMC 3876031. PMID 23663953.

- "Acute Treatment — Formula and Implementation of a Treatment Plan". Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder Second Edition. American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- "Main page". Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder Second Edition. American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- Calabrese JR, Huffman RF, White RL, Edwards S, Thompson TR, Ascher JA, Monaghan ET, Leadbetter RA (March 2008). "Lamotrigine in the acute treatment of bipolar depression: results of five double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials". Bipolar Disorders. 10 (2): 323–33. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00500.x. PMID 18271912.

- Geddes JR, Calabrese JR, Goodwin GM (January 2009). "Lamotrigine for treatment of bipolar depression: independent meta-analysis and meta-regression of individual patient data from five randomised trials". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 194 (1): 4–9. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048504. PMID 19118318.

- Reid JG, Gitlin MJ, Altshuler LL (July 2013). "Lamotrigine in psychiatric disorders". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 74 (7): 675–84. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08046. PMID 23945444.

- Backonja M (June 2004). "Neuromodulating drugs for the symptomatic treatment of neuropathic pain". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 8 (3): 212–6. doi:10.1007/s11916-004-0054-4. PMID 15115640.

- Jensen TS (2002). "Anticonvulsants in neuropathic pain: rationale and clinical evidence". European Journal of Pain. 6 Suppl A: 61–8. doi:10.1053/eujp.2001.0324. PMID 11888243.

- Pappagallo M (October 2003). "Newer antiepileptic drugs: possible uses in the treatment of neuropathic pain and migraine". Clinical Therapeutics. 25 (10): 2506–38. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.451.9407. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(03)80314-4. PMID 14667954.

- Bou Ghannam, Alaa; Pelak, Victoria S. (March 2017). "Visual Snow: a Potential Cortical Hyperexcitability Syndrome". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 19 (3): 9. doi:10.1007/s11940-017-0448-3. ISSN 1092-8480. PMID 28349350.

- Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA (December 2013). "Lamotrigine for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD006044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006044.pub4. PMC 6485508. PMID 24297457.

- Hussain A, Dar MA, Wani RA, Shah MS, Jan MM, Malik YA, Chandel RK, Margoob MA (2015). "Role of lamotrigine augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: a retrospective case review from South Asia". Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 37 (2): 154–8. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.155613. PMC 4418246. PMID 25969599.

- Medford, N. (2005). "Understanding and treating depersonalisation disorder". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (2): 92–100. doi:10.1192/apt.11.2.92.

- Hermle L, Simon M, Ruchsow M, Geppert M (October 2012). "Hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 2 (5): 199–205. doi:10.1177/2045125312451270. PMC 3736944. PMID 23983976.

- Erfurth A, Walden J, Grunze H (October 1998). "Lamotrigine in the treatment of schizoaffective disorder" (PDF). Neuropsychobiology. 38 (3): 204–5. doi:10.1159/000026540. PMID 9778612.

- Lieb K, Völlm B, Rücker G, Timmer A, Stoffers JM (January 2010). "Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 196 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.062984. PMID 20044651.

- Stein, DJ; Ipser, JC; Seedat, S (25 January 2006). "Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD002795. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002795.pub2. PMID 16437445.

- "Lamictal Prescribing Information" (PDF). GlaxoSmithKline. May 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- Serrani Azcurra DJ (Jun 2012). "Lamotrigine rechallenge after a skin rash. A combined study of open cases and a meta-analysis". Revista de Psiquiatria y Salud Mental. 6 (4): 144–9. doi:10.1016/j.rpsm.2012.04.002. PMID 23084805.

- http://www.rxlist.com/lamictal-drug.htm

- "Drug Label Information". Dailymed. National Institute of Health. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- Nicholson RJ, Kelly KP, Grant IS (February 1995). "Leucopenia associated with lamotrigine". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 310 (6978): 504. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6978.504b. PMC 2548879. PMID 7888892.

- Lamotrigine does not prolong QTc in a thorough QT/QTc study in healthy subjectsDixon R, Job S, Oliver R, Tompson D, Wright JG, Maltby K, Lorch U, Taubel J (September 2008). "Lamotrigine does not prolong QTc in a thorough QT/QTc study in healthy subjects". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 66 (3): 396–404. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03250.x. PMC 2526242. PMID 18662287.

- Motomura E, Tanii H, Usami A, Ohoyama K, Nakagawa M, Okada M (March 2012). "Lamotrigine-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome under risperidone treatment: a case report". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 24 (2): E38–9. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11040093. PMID 22772697.

- Ishioka M, Yasui-Furukori N, Hashimoto K, Sugawara N (July–August 2013). "Neuroleptic malignant syndrome induced by lamotrigine". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 36 (4): 131–2. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e318294799a. PMID 23783003.

- "Safety Alerts for Human Medical Products - Lamictal (lamotrigine): Drug Safety Communication - Serious Immune System Reaction". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- unknown, unknown. "Lamictal". National Institute of Health. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- Reimers A, Helde G, Brodtkorb E (September 2005). "Ethinyl estradiol, not progestogens, reduces lamotrigine serum concentrations". Epilepsia. 46 (9): 1414–7. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.10105.x. PMID 16146436.

- "PRODUCT INFORMATION LAMOTRIGINE SANDOZ 25MG, 50MG, 100MG, 200MG, DISPERSIBLE/CHEWABLE TABLETS". TGA eBusiness Services. Sandoz Pty Ltd. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Berwaerts K, Sienaert P, De Fruyt J (2009). "[Teratogenic effects of lamotrigine in women with bipolar disorder]". Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie (in Dutch). 51 (10): 741–50. PMID 19821242.

- Prabhu LV, Nasar MA, Rai R, Madhyastha S, Singh G (October 2007). "Lamotrigine in pregnancy: safety profile and the risk of malformations". Singapore Medical Journal. 48 (10): 880–3. PMID 17909669.

- Hale TW (2008). Medications and Mothers' Milk (13th ed.). Hale Publishing. p. 532. ISBN 978-0-9815257-2-3.

- anonymous. "Lamictal, Warnings & Precautions". RxList Inc. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- Glaxo Smith Klein Clinical Study Register, Study No. LAM40120: Lamotrigine (Lamictal®) Treatment in adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), A pilot study

- Öncü B, Er O, Çolak B, Nutt DJ (March 2014). "Lamotrigine for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder comorbid with mood disorders: a case series". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 28 (3): 282–3. doi:10.1177/0269881113493365. PMID 23784736.

- Foldvary N, Perry M, Lee J, Dinner D, Morris HH (December 2001). "The effects of lamotrigine on sleep in patients with epilepsy". Epilepsia. 42 (12): 1569–73. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.46100.x. PMID 11879368.

- Bonanni E, Galli R, Gori S, Pasquali L, Maestri M, Iudice A, Murri L (June 2001). "Neurophysiological evaluation of vigilance in epileptic patients on monotherapy with lamotrigine". Clinical Neurophysiology. 112 (6): 1018–22. doi:10.1016/S1388-2457(01)00537-5. PMID 11377260.

- Placidi F, Marciani MG, Diomedi M, Scalise A, Pauri F, Giacomini P, Gigli GL (August 2000). "Effects of lamotrigine on nocturnal sleep, daytime somnolence and cognitive functions in focal epilepsy". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 102 (2): 81–6. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.102002081.x. PMID 10949523.

- Sadler M (March 1999). "Lamotrigine associated with insomnia". Epilepsia. 40 (3): 322–5. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00712.x. PMID 10080513.

- http://www.ehealthme.com/ds/lamictal/myoclonic+jerks Retrieved August 19, 2010. Myoclonic Jerk in the use of Lamictal.

- Rogawski M (2002). "Chapter 1: Principles of antiepileptic drug action". In Levy RH, Mattson RH, Meldrum BS, Perucca E (eds.). Antiepileptic Drugs, Fifth Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 3–22. ISBN 9780781723213.

- "DailyMed - LAMOTRIGINE - lamotrigine chewable dispersible tablet, for suspension". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Rogawski MA, Löscher W (July 2004). "The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 5 (7): 553–64. doi:10.1038/nrn1430. PMID 15208697.

- Lees G, Leach MJ (May 1993). "Studies on the mechanism of action of the novel anticonvulsant lamotrigine (Lamictal) using primary neurological cultures from rat cortex". Brain Research. 612 (1–2): 190–9. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(93)91660-K. PMID 7687190.

- Thomas SP, Nandhra HS, Jayaraman A (April 2010). "Systematic review of lamotrigine augmentation of treatment resistant unipolar depression (TRD)". Journal of Mental Health. 19 (2): 168–75. doi:10.3109/09638230903469269. PMID 20433324.

- Ketter TA, Manji HK, Post RM (October 2003). "Potential mechanisms of action of lamotrigine in the treatment of bipolar disorders". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 23 (5): 484–95. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000088915.02635.e8. PMID 14520126.

- Braga MF, Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Post RM, Li H (March 2002). "Lamotrigine reduces spontaneous and evoked GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in the basolateral amygdala: implications for its effects in seizure and affective disorders". Neuropharmacology. 42 (4): 522–9. doi:10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00198-8. PMID 11955522.

- Shiah IS, Yatham LN, Gau YC, Baker GB (May 2003). "Effect of lamotrigine on plasma GABA levels in healthy humans". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 27 (3): 419–23. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00028-9. PMID 12691776.

- Southam E, Kirkby D, Higgins GA, Hagan RM (September 1998). "Lamotrigine inhibits monoamine uptake in vitro and modulates 5-hydroxytryptamine uptake in rats". European Journal of Pharmacology. 358 (1): 19–24. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00580-9. PMID 9809864.

- "LAMICTAL (lamotrigine) tablet". Daily Med. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- Ramsay RE, Pellock JM, Garnett WR, Sanchez RM, Valakas AM, Wargin WA, Lai AA, Hubbell J, Chern WH, Allsup T (1991). "Pharmacokinetics and safety of lamotrigine (Lamictal) in patients with epilepsy". Epilepsy Research. 10 (2–3): 191–200. doi:10.1016/0920-1211(91)90012-5. PMID 1817959.

- Cohen AF, Land GS, Breimer DD, Yuen WC, Winton C, Peck AW (November 1987). "Lamotrigine, a new anticonvulsant: pharmacokinetics in normal humans". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 42 (5): 535–41. doi:10.1038/clpt.1987.193. PMID 3677542.

- Werz MA (October 2008). "Pharmacotherapeutics of epilepsy: use of lamotrigine and expectations for lamotrigine extended release". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 4 (5): 1035–46. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S3343. PMC 2621406. PMID 19209284.

- Goa KL, Ross SR, Chrisp P (July 1993). "Lamotrigine. A review of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in epilepsy". Drugs. 46 (1): 152–76. doi:10.2165/00003495-199346010-00009. PMID 7691504.

- Anderson GD (May 1998). "A mechanistic approach to antiepileptic drug interactions". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 32 (5): 554–63. doi:10.1345/aph.17332. PMID 9606477.

- Engel, Jerome (2013). Seizures and Epilepsy. OUP USA. p. 567. ISBN 9780195328547.

- anonymous (19 March 2004). "EFFICACY SUPPLEMENTS APPROVED IN CALENDAR YEAR 2003". FDA/Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- "Treatment for epilepsy: generic lamotrigine". Department of Health (UK). 2 March 2005. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

External links

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Lamictal — documents related to the FDA approval process, including medical reviews and correspondence letters.

- Epilepsy South Africa: MEDICATION FOR EPILEPSY — an epilepsy FAQ with a list of medicines for treatment thereof, includes lamotrigine with South African trade name Lamictin

- Adverse Reactions — reported adverse reactions and side-effects.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal — Lamotrigine