Nordazepam

Nordazepam (INN; marketed under brand names Nordaz, Stilny, Madar, Vegesan, and Calmday; also known as nordiazepam, desoxydemoxepam, and desmethyldiazepam) is a 1,4-benzodiazepine derivative. Like other benzodiazepine derivatives, it has amnesic, anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, muscle relaxant, and sedative properties. However, it is used primarily in the treatment of anxiety disorders. It is an active metabolite of diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clorazepate, prazepam, pinazepam, and medazepam.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Nordiazepam, desoxydemoxepam, desmethyldiazepam |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ? |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 36-200 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.012.840 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

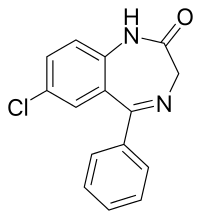

| Formula | C15H11ClN2O |

| Molar mass | 270.71 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Nordazepam is among the longest lasting (longest half-life) benzodiazepines, and its occurrence as a metabolite is responsible for most cumulative side-effects of its myriad of pro-drugs when they are used repeatedly at moderate-high doses; the nordazepam metabolite oxazepam is also active (and is a more potent, full BZD-site agonist), which contributes to nordazepam cumulative side-effects but occur too minutely to contribute to the cumulative side-effects of nordazepam pro-drugs (except when they are abused chronically in extremely supra-therapeutic doses). (citations?)

Side effects

Common side effects of nordazepam include somnolence, which is more common in elderly patients and/or people on high-dose regimens. Hypotonia, which is much less common, is also associated with high doses and/or old age.

Contraindications and special caution

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals, and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[3] As with many other drugs, changes in liver function associated with aging or diseases such as cirrhosis, may lead to impaired clearance of nordazepam.[4]

Pharmacology

Nordazepam is a partial agonist at the GABAA receptor, which makes it less potent than other benzodiazepines, particularly in its amnesic and muscle-relaxing effects.[5] Its elimination half life is between 36 and 200 hours, with wide variation among individuals; factors such as age and gender are known to impact it.[1] The variation of reported half-lifes are attributed to differences in nordazepam metabolism and that of its metabolites as nordazepam is hydroxylated to active metabolites such as oxazepam, before finally being glucuronidated and excreted in the urine.[6] This can be attributed to extremely variable hepatic and renal metabolic functions among individuals depending upon a number of factors (including age, ethnicity, disease, and current or previous use/abuse of other drugs/medicines).

Pregnancy and nursing mothers

Nordazepam, like other benzodiazepines, easily crosses the placental barrier, so the drug should not be administered during the first trimester of pregnancy.[7] In case of serious medical reasons, nordazepam can be given in late pregnancy, but the foetus, due to the pharmacological action of the drug, may experience side effects such as hypothermia, hypotonia, and sometimes mild respiratory depression. Since nordazepam and other benzodiazepines are excreted in breast milk, the substance should not be administered to mothers who are breastfeeding. Discontinuing of breast-feeding is indicated for regular intake by the mother.[8]

Recreational use

Nordazepam and other sedative-hypnotic drugs are detected frequently in cases of people suspected of driving under the influence of drugs. Many drivers have blood levels far exceeding the therapeutic dose range, suggesting benzodiazepines are commonly used in doses higher than the recommended doses.[9]

See also

References

- C. Heather Ashton (March 2007). "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- Ator NA, Griffiths RR (September 1997). "Selectivity in the generalization profile in baboons trained to discriminate lorazepam: benzodiazepines, barbiturates and other sedative/anxiolytics". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 282 (3): 1442–57. PMID 9316858.

- Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, AA.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, PM.; Eschalier, A. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Ann Pharm Fr. 67 (6): 408–413. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- Klotz U, Müller-Seydlitz P (January 1979). "Altered elimination of desmethyldiazepam in the elderly". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 7 (1): 119–20. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb00908.x. PMC 1429605. PMID 367407.

- Gobbi M, Barone D, Mennini T, Garattini S (May 1987). "Diazepam and desmethyldiazepam differ in their affinities and efficacies at 'central' and 'peripheral' benzodiazepine receptors". J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 39 (5): 388–91. doi:10.1111/j.2042-7158.1987.tb03404.x. PMID 2886589.

- Marland, A (Jan–Feb 1999). "The urinary elimination profiles of diazepam and its metabolites, nordiazepam, temazepam, and oxazepam, in the equine after a 10-mg intramuscular dose". J Anal Toxicol. 23 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1093/jat/23.1.29. PMID 10022206.

- Olive G, Rey E (1983). "[Benzodiazepines and pregnancy. Transplacental passage, labor and lactation]". L'Encéphale (in French). 9 (4 Suppl 2): 87B–96B. PMID 6144535.

- Dusci LJ, Good SM, Hall RW, Ilett KF (January 1990). "Excretion of diazepam and its metabolites in human milk during withdrawal from combination high dose diazepam and oxazepam". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 29 (1): 123–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03612.x. PMC 1380071. PMID 2105100.

- Jones AW; Holmgren A; Kugelberg FC. (April 2007). "Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results". Ther Drug Monit. 29 (2): 248–60. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d3c04. PMID 17417081.