Ethisterone

Ethisterone, also known as ethinyltestosterone, pregneninolone, and anhydrohydroxyprogesterone and formerly sold under the brand names Proluton C and Pranone among others, is a progestin medication which was used in the treatment of gynecological disorders but is now no longer available.[3][4][5] It was used alone and was not formulated in combination with an estrogen.[1][6] The medication is taken by mouth.[4]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Proluton C, Pranone, others |

| Other names | Ethinyltestosterone; Ethynyltestosterone; Pregneninolone; Anhydrohydroxyprogesterone; Etisteron; Pregnin; Ethindrone |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, sublingual[1] |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Progestin; Androgen; Anabolic steroid |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolites | • 5α-Dihydroethisterone[2] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.452 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H28O2 |

| Molar mass | 312.446 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects of ethisterone include masculinization among others.[4][7][8] Ethisterone is a progestin, or a synthetic progestogen, and hence is an agonist of the progesterone receptor, the biological target of progestogens like progesterone.[9] It has some androgenic and anabolic activity and no other important hormonal activity.[9][10][11][12][13]

Ethisterone was discovered in 1938 and was introduced for medical use in Germany in 1939 and in the United States in 1945.[14][15][16] It was the second progestogen to be marketed, following injected progesterone in 1934, and was both the first orally active progestogen and the first progestin to be introduced.[17][18][15] Ethisterone was followed by the improved and much more widely used and known progestin norethisterone in 1957.[19][20]

Medical uses

Ethisterone was used in the treatment of gynecological disorders such as irregular menstruation, amenorrhea, and premenstrual syndrome.[3][21]

Side effects

Side effects of ethisterone include symptoms of masculinization such as acne and hirsutism among others.[4][7][8]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Ethisterone has weak progestogenic activity and weak androgenic activity, but does not seem to have estrogenic activity.[9][12][23]

| Compound | PR | AR | ER | GR | MR | SHBG | CBG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethisterone | 35 | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | ? | ? |

| 5α-Dihydroethisterone | 12 | 38–100a | 4 | 120 | ? | 100 | ? |

| Norethisterone | 155 | 45 | <1 | 3 | <1 | 16 | <1 |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were progesterone for the PR, testosterone (a = DHT) for the AR, E2 for the ER, DEXA for the GR, aldosterone for the MR, DHT for SHBG, and cortisol for CBG. Sources: See template. | |||||||

| AR | ERα | ERβ | PR | GR | SHBG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | RBA | IC50 | RBA | IC50 | RBA | IC50 | RBA | IC50 | RBA | Kd | RBA |

| 0.5–16 nM | 38–100% | 229 nM | 3.5% | >10,000 nM | IA | 130 nM | 12% | 7 nM | 120% | 0.18 nM | 100% |

| Notes: IC50 values are for binding inhibition (affinity). Reference ligands for RBA (100%) were DHT for the AR, estradiol for the ERα and ERβ, progesterone for the PR, dexamethasone for the GR, and DHT for SHBG. Sources: See template. | |||||||||||

Ethisterone is a major active metabolite of danazol (2,3-isoxazolethisterone), and is thought to contribute importantly to its effects.[23]

Progestogenic activity

Ethisterone is a progestogen, or an agonist of the progesterone receptors.[9] It has about 44% of the affinity of progesterone for the progesterone receptor.[24] The medication is described as a relatively weak progestogen, similarly to its analogue dimethisterone.[25] Ethisterone has about 20-fold lower potency as a progestogen relative to norethisterone.[26] It is said to have minimal antigonadotropic effect and to not suppress ovulation, which has precluded its use in hormonal contraception.[23]

Androgenic activity

Based on in vitro research, ethisterone and norethisterone are about equipotent in their EC50 values for activation of the androgen receptor (AR), whereas, conversely, norethisterone shows markedly increased potency relative to ethisterone in terms of its EC50 for the progesterone receptor.[9] As such, there is a considerable separation in the ratios of androgenic and progestogenic activity for ethisterone and norethisterone.[9] Moreover, at the larger dosages in which it is used to achieve equivalent progestogenic effect, ethisterone has more androgenic effect relative to norethisterone and other 19-nortestosterone progestins.[10][11] However, the androgenic activity of ethisterone has in any case been described as weak.[23] Due to its androgenic activity, ethisterone has been associated with the masculinization of female fetuses in women who have taken it during pregnancy.[8] The 5α-reduced metabolite of ethisterone, 5α-dihydroethisterone, has been found to show reduced androgenic activity relative to ethisterone.[2]

Estrogenic activity

Testosterone is aromatized into estradiol, and norethisterone, the 19-nortestosterone analogue of ethisterone, has similarly been shown to be aromatized into ethinylestradiol.[27] In accordance, high doses of norethisterone have been found to be associated with marked increases in urinary estrogen excretion (due to metabolism into ethinylestradiol), as well as with high rates of estrogenic side effects such as breast enlargement in women and gynecomastia in men and improvement of menopausal symptoms in postmenopausal women.[12][28] In contrast, ethisterone and other progestogens such as progesterone and hydroxyprogesterone caproate do not increase estrogen excretion and are not associated with estrogenic effects, indicating that they have little or no estrogenic activity.[12][13] Similarly, although ethisterone showed estrogenic effects in the uterus and vagina in rats, few or no such effects were observed in women treated with the medication, even at very high doses.[29][30] As such, ethisterone does not appear to share the estrogenic activity of norethisterone, at least in humans.[12][13][23]

Pharmacokinetics

Ethisterone is active both orally and sublingually in humans.[31] Good oral bioavailability of ethisterone has been observed in rats.[31] The medication was the first orally active progestin to be discovered and introduced for clinical use.[31] Ethisterone is not converted into pregnanediol in humans, indicating that it is not metabolized into progesterone.[31] No aromatization of ethisterone has been detected in vivo, and no estrogenic metabolites were observed in vitro upon incubation of ethisterone in placental homogenates.[31] Ethisterone has relatively high affinity for sex hormone-binding globulin, about 14% of that of dihydrotestosterone and 49% of that of testosterone in one study.[32]

Chemistry

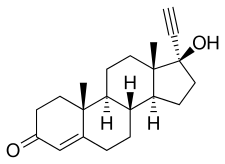

Ethisterone is a synthetic androstane steroid which was derived from testosterone and is also known by the following synonyms:[33][34]

- 17α-Ethynyltestosterone (or simply ethinyltestosterone or ethynyltestosterone)

- 17α-Ethynylandrost-4-en-17β-ol-3-one

- 17α-Pregn-4-en-20-yn-17β-ol-3-one (or simply pregneninolone or pregnenynolone)[35][36]

- 20,21-Anhydro-17β-hydroxyprogesterone (or simply anhydrohydroxyprogesterone)[37]

Closely related analogues of ethisterone include dimethisterone (6α,21-dimethylethisterone), norethisterone (19-norethisterone), and danazol (the 2,3-d-isoxazole ring-fused derivative of ethisterone), as well as vinyltestosterone, allyltestosterone, methyltestosterone, ethyltestosterone, and propyltestosterone.

Synthesis

Chemical syntheses of ethisterone have been published.[31]

History

Ethisterone was synthesized in 1938 by Hans Herloff Inhoffen, Willy Logemann, Walter Hohlweg, and Arthur Serini at Schering AG in Berlin.[14] It was derived from testosterone via ethynylation at the C17α position, and it was hoped, that, analogously to estradiol and ethinylestradiol, ethisterone would be an orally active form of testosterone.[38] However, the androgenic activity of ethisterone was attenuated and it showed considerable progestogenic activity.[38] As such, it was developed as a progestogen instead and was introduced for medical use in Germany in 1939 as Proluton C and by Schering in the United States in 1945 as Pranone.[15][16] Ethisterone remained in use as late as 2000.[34]

Society and culture

Generic names

Ethisterone is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, and BAN, while ethistérone is its DCF.[33][34][4] It has also been referred to as ethinyltestosterone, pregneninolone, and anhydrohydroxyprogesterone.[33][34][4]

Brand names

Ethisterone has been marketed under a variety of brand names including Amenoren, Cycloestrol-AH Progestérone, Duosterone, Estormon, Etherone, Ethisteron, Luteosterone, Lutocyclin, Lutocylol, Lutogynestryl, Menstrogen, Nugestoral, Oophormin Luteum, Ora-Lutin, Orasecron, Pranone, Pre Ciclo, Prodroxan, Produxan, Progestab, Progesteron lingvalete, Progestoral, Proluton C, Syngestrotabs, and Trosinone among others.[33][34][22][39]

References

- University of California (1868-1952) (1952). Hospital Formulary and Compendium of Useful Information. University of California Press. pp. 49–. GGKEY:2UAAZRZ5LN0.

- Lemus AE, Enríquez J, García GA, Grillasca I, Pérez-Palacios G (1997). "5alpha-reduction of norethisterone enhances its binding affinity for androgen receptors but diminishes its androgenic potency". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 60 (1–2): 121–9. doi:10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00172-0. PMID 9182866.

- Swyer GI (1950). "Oral Hormonal Therapy for Menstrual Disorders". Br Med J. 1 (4654): 626–34. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4654.626. PMC 2037145. PMID 20787798.

- Dr. Ian Morton; I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (31 October 1999). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-7514-0499-9.

- https://www.drugs.com/international/ethisterone.html

- Elsie Evelyn Krug (1963). Pharmacology in nursing. Mosby.

- Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 872–. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- Wilkins, Lawson; Jones, Howard W.; Holman, Gerald H.; Stempfel, Robert S. (1958). "Masculinization of the Female Fetus Associated with Administration of Oral and Intramuscular Progestins During Gestation: Non-Adrenal Female Pseudohermaphrodism". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 18 (6): 559–585. doi:10.1210/jcem-18-6-559. ISSN 0021-972X.

- McRobb L, Handelsman DJ, Kazlauskas R, Wilkinson S, McLeod MD, Heather AK (2008). "Structure-activity relationships of synthetic progestins in a yeast-based in vitro androgen bioassay". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 110 (1–2): 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.10.008. PMID 18395441.

- P. J. Bentley (1980). Endocrine Pharmacology: Physiological Basis and Therapeutic Applications. CUP Archive. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-521-22673-8.

- Richard M. Eglen; Mont R. Juchau; Gillian Edwards; Arthur H. Weston, Helen Wise, M. D. Murray, D. Craig Brater, Olivier Valdenaire, Philippe Vernier, Annemarie Polak; et al. (6 December 2012). Progress in Drug Research: Fortschritte der Arzneimittelforschung / Progrès des recherches pharmaceutiques. Birkhäuser. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-3-0348-8863-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Paulsen CA, Leach RB, Lanman J, Goldston N, Maddock WO, Heller CG (1962). "Inherent estrogenicity of norethindrone and norethynodrel: comparison with other synthetic progestins and progesterone". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 22: 1033–9. doi:10.1210/jcem-22-10-1033. PMID 13942007.

- Troop RC, Possanza GJ (1962). "Gonadal influences on the pituitary-adrenal axis". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 98: 444–9. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(62)90210-2. PMID 13922599.

- Marc A. Fritz; Leon Speroff (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 963–964. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3.

The discovery of ethinyl substitution and oral potency led (at the end of the 1930s) to the preparation of ethisterone, an orally active derivative of testosterone. In 1951, it was demonstrated that removal of the 19-carbon from ethisterone to form norethindrone did not destroy the oral activity, and most importantly, it changed the major hormonal effect from that of an androgen to that of a progestational agent. Accordingly, the progestational derivatives of testosterone were designated as 19-nortestosterones (denoting the missing 19-carbon).

- Christian Lauritzen; John W. W. Studd (22 June 2005). Current Management of the Menopause. CRC Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-203-48612-2.

Ethisterone, the first orally effective progestagen, was synthesized by Inhoffen and Hohlweg in 1938. Norethisterone, a progestogen still used worldwide, was synthesized by Djerassi in 1951. But this progestogen was not used immediately and in 1953 Colton discovered norethynodrel, used by Pincus in the first oral contraceptive. Numerous other progestogens were subsequently synthesized, e.g., lynestrenol and ethynodiol diacetate, which were, in fact, prhormones converted in vivo to norethisterone. All these progestogens were also able to induce androgenic effects when high doses were used. More potent progestogens were synthesized in the 1960s, e.g. norgestrel, norgestrienone. These progestogens were also more androgenic.

- Klaus Roth (2014). Chemische Leckerbissen. John Wiley & Sons. p. 69. ISBN 978-3-527-33739-2.

Im Prinzip hatten Hohlweg und Inhoffen die Lösung schon 1938 in der Hand, denn ihr Ethinyltestosteron (11) war eine oral wirksame gestagene Verbindung und Schering hatte daraus bereits 1939 ein Medikament (Proluton C®) entwickelt.

- Gray Huntington Twombly (1947). Endocrinology of Neoplastic Diseases: A Symposium by Eighteen Authors. Oxford University Press. p. 7.

- William Andrew Publishing (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. Elsevier. pp. 1504–1505. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

- C. Wayne Bardin (22 October 2013). Recent Progress in Hormone Research - Volume 50: Proceedings of the 1993 Laurentian Hormone Conference. Elsevier Science. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-1-4832-8903-8.

- Lara Marks (2010). Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill. Yale University Press. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-0-300-16791-7.

- Dalton K (1959). "2. Menstrual Disorders in General Practice". Journal of the College of General Practitioners and research newsletter. 2 (3): 236. PMC 1890213.

- Axel Kleemann; Jürgen Engel (2001). Pharmaceutical Substances: Syntheses, Patents, Applications. Thieme. p. 800. ISBN 978-3-13-558404-1.

- Barbieri RL, Ryan KJ (October 1981). "Danazol: endocrine pharmacology and therapeutic applications". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 141 (4): 453–63. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(81)90611-6. PMID 7025640.

- Franz v. Bruchhausen; Gerd Dannhardt; Siegfried Ebel; August W. Frahm, Eberhard Hackenthal, Ulrike Holzgrabe (2 July 2013). Hagers Handbuch der Pharmazeutischen Praxis: Band 8: Stoffe E-O. Springer-Verlag. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-3-642-57994-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Robert J. Kurman (17 April 2013). Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 390–. ISBN 978-1-4757-3889-6.

- Regidor PA, Schindler AE (2017). "Antiandrogenic and antimineralocorticoid health benefits of COC containing newer progestogens: dienogest and drospirenone". Oncotarget. 8 (47): 83334–83342. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.19833. PMC 5669973. PMID 29137347.

- Kuhl H, Wiegratz I (2007). "Can 19-nortestosterone derivatives be aromatized in the liver of adult humans? Are there clinical implications?". Climacteric. 10 (4): 344–53. doi:10.1080/13697130701380434. PMID 17653961.

- Paulsen CA (March 1965). "Progestin metabolism: special reference to estrogenic pathways". Metab. Clin. Exp. 14: SUPPL:313–9. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(65)90018-1. PMID 14261416.

- Salmon, U. J.; Salmon, A. A. (1940). "Effect of Pregneninolone (17-Ethinyl Testosterone) on Genital Tract of Immature Female Rats". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 43 (4): 709–711. doi:10.3181/00379727-43-11311P. ISSN 1535-3702.

- Salmon, U. J.; Geist, S. H. (1940). "Biological Properties of Pregneninolone (17-Ethinyl Testosterone) in Women". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 45 (2): 522–525. doi:10.3181/00379727-45-11738P. ISSN 1535-3702.

- Die Gestagene. Springer-Verlag. 27 November 2013. pp. 11–12, 282. ISBN 978-3-642-99941-3.

- Pugeat MM, Dunn JF, Nisula BC (July 1981). "Transport of steroid hormones: interaction of 70 drugs with testosterone-binding globulin and corticosteroid-binding globulin in human plasma". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 53 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1210/jcem-53-1-69. PMID 7195405.

- J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. p. 508. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 413–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- Roche Review ... Hoffman-La Roche, and Roche-organon. 1940.

Hohlweg, Naturwiss., 1938, 26:96, added the ethinyl radical to testosterone and obtained pregneninolone. This substance has been referred to in the literature as Δ4 pregnen-in-20-on-3-ol-17; Δ4 pregnene-in, 17-ol, 3-one; ethinyl testosterone; anhydro-oxy-progesterone; anhydro-hydroxy-progesterone; and pregneninolone.

- Inhoffen, H. H.; Hohlweg, W. (1938). "Neue per os-wirksame weibliche Keimdrüsenhormon-Derivate: 17-Aethinyl-oestradiol und Pregnen-in-on-3-ol-17". Die Naturwissenschaften. 26 (6): 96–96. doi:10.1007/BF01681040. ISSN 0028-1042.

- Davis ME, Wied GL (1957). "17α-Hydroxyprogesterone acetate: An effective progestational substance on oral administration". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 17 (10): 1237–44. doi:10.1210/jcem-17-10-1237. PMID 13475464.

- Kuhl H (2011). "Pharmacology of Progestogens" (PDF). J Reproduktionsmed Endokrinol. 8 (1): 157–177.

- Muller (19 June 1998). European Drug Index: European Drug Registrations, Fourth Edition. CRC Press. pp. 457–. ISBN 978-3-7692-2114-5.

- http://www.micromedexsolutions.com

Further reading

- Inhoffen HH, Logemann W, Hohlweg W, Serini A (May 4, 1938). "Untersuchungen in der Sexualhormon-Reihe (Investigations in the sex hormone series)". Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 71 (5): 1024–32. doi:10.1002/cber.19380710520. Archived from the original (abstract page) on December 17, 2012.

- Petrow V (1970). "The contraceptive progestagens". Chem Rev. 70 (6): 713–26. doi:10.1021/cr60268a004. PMID 4098492.

- Kugener, André (2004). Tabletten der Fa. Schering (Tablets of Schering AG) Proluton C tablets c. 1939

- Quinkert G (2004). "Hans Herloff Inhoffen in His Times (1906-1992)". Eur J Org Chem. 2004 (17): 3727–48. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200300813. Archived from the original (abstract page) on 2012-12-16.

- Sneader, Walter (2005). "Hormone analogues". Drug discovery : a history. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 188–225. ISBN 0-471-89980-1.

- Djerassi C (2006). "Chemical birth of the pill". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 194 (1): 290–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.010. PMID 16389046.