Metandienone

Metandienone, also known as methandienone or methandrostenolone and sold under the brand name Dianabol among others, is an androgen and anabolic steroid (AAS) medication which is mostly no longer used.[3][4][1][5] It is also used non-medically for physique- and performance-enhancing purposes.[1] It is often taken by mouth.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Dianabol, others |

| Other names | Methandienone; Methandrostenolone; Methandrolone; Dehydromethyltestosterone; Methylboldenone; Perabol; Ciba-17309-Ba; TMV-17; NSC-51180; NSC-42722; 17α-Methyl-δ1-testosterone; 17α-Methylandrost-1,4-dien-17β-ol-3-one |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular injection (veterinary)[1] |

| Drug class | Androgen; Anabolic steroid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | High |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 3–6 hours[1][2] |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.716 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H28O2 |

| Molar mass | 300.441 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects of metandienone include symptoms of masculinization like acne, increased hair growth, voice changes, and increased sexual desire, estrogenic effects like fluid retention and breast enlargement, and liver damage.[1] The drug is an agonist of the androgen receptor (AR), the biological target of androgens like testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and has strong anabolic effects and moderate androgenic effects.[1] It also has moderate estrogenic effects.[1]

Metandienone was originally developed in 1955 by CIBA and marketed in Germany and the United States.[1][6][3][7][8] As the CIBA product Dianabol, metandienone quickly became the first widely used AAS among professional and amateur athletes, and remains the most common orally active AAS for non-medical use.[9][7][10][11] It is currently a controlled substance in the United States[12] and United Kingdom[13] and remains popular among bodybuilders. Metandienone is readily available without a prescription in certain countries such as Mexico, and is also manufactured in some Asian countries.[5]

Medical uses

Metandienone was formerly approved and marketed as a form of androgen replacement therapy for the treatment of hypogonadism in men, but has since been discontinued and withdrawn in most countries, including in the United States.[14][3][5]

It was given at a dosage of 5 to 10 mg/day in men and 2.5 mg/day in women.[15][16][1]

| Route | Medication | Major brand names | Form | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Testosteronea | – | Tablet | 400–800 mg/day (in divided doses) |

| Testosterone undecanoate | Andriol, Jatenzo | Capsule | 40–80 mg/2–4x day (with meals) | |

| Methyltestosteroneb | Android, Metandren, Testred | Tablet | 10–50 mg/day | |

| Fluoxymesteroneb | Halotestin, Ora-Testryl, Ultandren | Tablet | 5–20 mg/day | |

| Metandienoneb | Dianabol | Tablet | 5–15 mg/day | |

| Mesteroloneb | Proviron | Tablet | 25–150 mg/day | |

| Buccal | Testosterone | Striant | Tablet | 30 mg 2x/day |

| Methyltestosteroneb | Metandren, Oreton Methyl | Tablet | 5–25 mg/day | |

| Sublingual | Testosteroneb | Testoral | Tablet | 5–10 mg 1–4x/day |

| Methyltestosteroneb | Metandren, Oreton Methyl | Tablet | 10–30 mg/day | |

| Intranasal | Testosterone | Natesto | Nasal spray | 11 mg 3x/day |

| Transdermal | Testosterone | AndroGel, Testim, TestoGel | Gel | 25–125 mg/day |

| Androderm, AndroPatch, TestoPatch | Non-scrotal patch | 2.5–15 mg/day | ||

| Testoderm | Scrotal patch | 4–6 mg/day | ||

| Axiron | Axillary solution | 30–120 mg/day | ||

| Androstanolone (DHT) | Andractim | Gel | 100–250 mg/day | |

| Rectal | Testosterone | Rektandron, Testosteronb | Suppository | 40 mg 2–3x/day |

| Injection (IM or SC) | Testosterone | Andronaq, Sterotate, Virosterone | Aqueous suspension | 10–50 mg 2–3x/week |

| Testosterone propionateb | Testoviron | Oil solution | 10–50 mg 2–3x/week | |

| Testosterone enanthate | Delatestryl | Oil solution | 50–250 mg 1x/1–4 weeks | |

| Xyosted | Auto-injector | 50–100 mg 1x/week | ||

| Testosterone cypionate | Depo-Testosterone | Oil solution | 50–250 mg 1x/1–4 weeks | |

| Testosterone isobutyrate | Agovirin Depot | Aqueous suspension | 50–100 mg 1x/1–2 weeks | |

| Mixed testosterone esters | Sustanon 100, Sustanon 250 | Oil solution | 50–250 mg 1x/2–4 weeks | |

| Testosterone undecanoate | Aveed, Nebido | Oil solution | 750–1,000 mg 1x/10–14 weeks | |

| Testosterone buciclatea | – | Aqueous suspension | 600–1,000 mg 1x/12–20 weeks | |

| Implant | Testosterone | Testopel | Pellet | 150–1,200 mg/3–6 months |

| Notes: Men produce about 3 to 11 mg testosterone per day (mean 7 mg/day in young men). Footnotes: a = Never marketed. b = No longer used and/or no longer marketed. Sources: See template. | ||||

Non-medical uses

Metandienone is used for physique- and performance-enhancing purposes by competitive athletes, bodybuilders, and powerlifters.[1] It is said to be the most widely used AAS for such purposes both today and historically.[1]

Side effects

Androgenic side effects such as oily skin, acne, seborrhea, increased facial/body hair growth, scalp hair loss, and virilization may occur.[1] Estrogenic side effects such as gynecomastia and fluid retention can also occur.[1] Case reports of gynecomastia exist.[20][21] As with other 17α-alkylated steroids, metandienone poses a risk of hepatotoxicity and use over extended periods of time can result in liver damage without appropriate precautions.[1]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Medication | Ratioa |

|---|---|

| Testosterone | ~1:1 |

| Androstanolone (DHT) | ~1:1 |

| Methyltestosterone | ~1:1 |

| Methandriol | ~1:1 |

| Fluoxymesterone | 1:1–1:15 |

| Metandienone | 1:1–1:8 |

| Drostanolone | 1:3–1:4 |

| Metenolone | 1:2–1:30 |

| Oxymetholone | 1:2–1:9 |

| Oxandrolone | 1:3–1:13 |

| Stanozolol | 1:1–1:30 |

| Nandrolone | 1:3–1:16 |

| Ethylestrenol | 1:2–1:19 |

| Norethandrolone | 1:1–1:20 |

| Notes: In rodents. Footnotes: a = Ratio of androgenic to anabolic activity. Sources: See template. | |

Metandienone binds to and activates the androgen receptor (AR) in order to exert its effects.[22] These include dramatic increases in protein synthesis, glycogenolysis, and muscle strength over a short space of time. While it can be metabolized by 5α-reductase into methyl-1-testosterone (17α-methyl-δ1-DHT), a more potent AAS, the drug has extremely low affinity for this enzyme and methyl-1-testosterone is thus produced in only trace amounts.[1][23] As such, 5α-reductase inhibitors like finasteride and dutasteride do not reduce the androgenic effects of metandienone.[1] Nonetheless, while the ratio of anabolic to androgenic activity of metandienone is improved relative to that of testosterone, the drug does still possess moderate androgenic activity and is capable of producing severe virilization in women and children.[1] As such, it is only really commonly used in men.[1]

Metandienone is a substrate for aromatase and can be metabolized into the estrogen methylestradiol (17α-methylestradiol).[1] While the rate of aromatization is reduced relative to that for testosterone or methyltestosterone, the estrogen produced is metabolism-resistant and hence metandienone retains moderate estrogenic activity.[1] As such, it can cause side effects such as gynecomastia and fluid retention.[1] The co-administration of an antiestrogen such as an aromatase inhibitor like anastrozole or a selective estrogen receptor modulator like tamoxifen can reduce or prevent such estrogenic side effects.[1] Metandienone has no progestogenic activity.[1]

As with other 17α-alkylated AAS, metandienone is hepatotoxic.[1]

Pharmacokinetics

Metandienone has high oral bioavailability.[1] It has very low affinity for human serum sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), about 10% of that of testosterone and 2% of that of DHT.[24] The drug is metabolized in the liver by 6β-hydroxylation, 3α- and 3β-oxidation, 5β-reduction, 17-epimerization, and conjugation among other reactions.[23] Unlike methyltestosterone, owing to the presence of its C1(2) double bond, metandienone does not produce 5α-reduced metabolites.[23][1][25] The elimination half-life of metandienone is about 3 to 6 hours.[1][2] It is eliminated in the urine.[23]

Chemistry

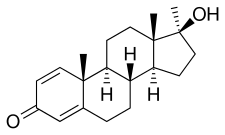

Metandienone, also known as 17α-methyl-δ1-testosterone or as 17α-methylandrost-1,4-dien-17β-ol-3-one, is a synthetic androstane steroid and a 17α-alkylated derivative of testosterone.[6] It is a modification of testosterone with a methyl group at the C17α position and an additional double bond between the C1 and C2 positions.[6] The drug is also the 17α-methylated derivative of boldenone (δ1-testosterone) and the δ1 analogue of methyltestosterone (17α-methyltestosterone).[6]

Detection in body fluids

Metandienone is subject to extensive hepatic biotransformation by a variety of enzymatic pathways. The primary urinary metabolites are detectable for up to 3 days, and a recently discovered hydroxymethyl metabolite is found in urine for up to 19 days after a single 5 mg oral dose.[26] Several of the metabolites are unique to metandienone. Methods for detection in urine specimens usually involve gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.[27][28]

History

Metandienone was first described in 1955.[1] It was synthesized by researchers at the CIBA laboratories in Basel, Switzerland. CIBA filed for a U.S. patent in 1957,[29] and began marketing the drug as Dianabol in 1958 in the U.S.[1][30] It was initially prescribed to burn victims and the elderly. It was also prescribed off-label as a pharmaceutical performance enhancement to weight lifters and other athletes.[31] Early adopters included players for Oklahoma University and San Diego Chargers head coach Sid Gillman, who administered Dianabol to his team starting in 1963.[32]

After the Kefauver Harris Amendment was passed in 1962, the U.S. FDA began the DESI review process to ensure the safety and efficacy of drugs approved under the more lenient pre-1962 standards, including Dianabol.[33] In 1965, the FDA pressured CIBA to further document its legitimate medical uses, and re-approved the drug for treating post-menopausal osteoporosis and pituitary-deficient dwarfism.[34] After CIBA's patent exclusivity period lapsed, other manufacturers began to market generic metandienone in the U.S.

Following further FDA pressure, CIBA withdrew Dianabol from the U.S. market in 1983.[1] Generic production shut down two years later, when the FDA revoked metandienone's approval entirely in 1985.[1][34][35] Non-medical use was outlawed in the U.S. under the Anabolic Steroids Control Act of 1990.[36] While metandienone is controlled and no longer medically available in the U.S., it continues to be produced and used medically in some other countries.[1]

Society and culture

Generic names

Metandienone is the generic name of the drug and its INN, while methandienone is its BAN and métandiénone is its DCF.[6][3][4][5] It is also referred to as methandrostenolone and as dehydromethyltestosterone.[6][3][4][1][5] The former synonym should not be confused with methylandrostenolone, which is another name for a different AAS known as metenolone.[3]

Brand names

Metandienone was introduced and formerly sold primarily under the brand name Dianabol.[6][3][4][5][1] It has also been marketed under a variety of other brand names including Anabol, Averbol, Chinlipan, Danabol, Dronabol, Metanabol, Methandon, Naposim, Reforvit-B, and Vetanabol among others.[6][3][4][5][1]

Legal status

Metandienone, along with other AAS, is a schedule III controlled substance in the United States under the Controlled Substances Act.[37]

Doping in sports

There are many known cases of doping in sports with metandienone by professional athletes.

References

- Llewellyn W (2011). Anabolics. Molecular Nutrition Llc. pp. 444–454, 533. ISBN 978-0-9828280-1-4.

- Pedro Ruiz; Eric C. Strain (2011). Lowinson and Ruiz's Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Textbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 358–. ISBN 978-1-60547-277-5.

- Swiss Pharmaceutical Society (2000). "Metandienone". Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. p. 660. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- "Metandienone". drugs.com.

- Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 781–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- Yesalis CE, Anderson WA, Buckley WE, Wright JE (1990). "Incidence of the nonmedical use of anabolic-androgenic steroids" (PDF). NIDA Research Monograph. 102: 97–112. PMID 2079979.

- Fair JD (1993). "Isometrics or Steroids? Exploring New Frontiers Of Strength in the Early 1960s" (PDF). Journal of Sport History. 20 (1): 1–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-28.

- Yesalis C, Bahrke M (2002). "History of Doping in Sport" (PDF). International Sports Studies. 24: 42–76.

- Lin GC, Erinoff L (1996-07-01). Anabolic Steroid Abuse. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7881-2969-8.

- Helms E (August 2014). "What can be achieved as a natural bodybuilder?" (PDF). Alan Aragon's Research Review. Alan Aragon.

- "Controlled Substances, Alphabetical Order" (PDF). Unitied States Drug Enforcement Administration. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "List of most commonly encountered drugs currently controlled under the misuse of drugs legislation". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- Barceloux DG (3 February 2012). Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 275–. ISBN 978-1-118-10605-1.

- Fruehan, Alice E. (1963). "Current Status of Anabolic Steroids". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 184 (7): 527. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03700200049009. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ABPI Data Sheet Compendium. Pharmind Pub. 1978.

- National Drug Code Directory. Consumer Protection and Environmental Health Service, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. 1982. pp. 642–.

- Federal Register. Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration. 18 January 1983. pp. 2208–2209.

- The National Formulary ... American Pharmaceutical Association. 1974.

Tablets available — Methandrostenolone Tablets usually available contain the following amounts of methandrostenolone: 2.5 and 5 mg.

- Ralph I. Dorfman (5 December 2016). Steroidal Activity in Experimental Animals and Man. Elsevier Science. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-1-4832-7300-6.

- Laron, Zvi (1962). "Breast Development Induced by Methandrostenolone (Dianabol)". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 22 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1210/jcem-22-4-450. ISSN 0021-972X.

- Roselli CE (May 1998). "The effect of anabolic-androgenic steroids on aromatase activity and androgen receptor binding in the rat preoptic area". Brain Research. 792 (2): 271–6. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00148-6. PMID 9593936.

- Schänzer W, Geyer H, Donike M (April 1991). "Metabolism of metandienone in man: identification and synthesis of conjugated excreted urinary metabolites, determination of excretion rates and gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric identification of bis-hydroxylated metabolites". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 38 (4): 441–64. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(91)90332-y. PMID 2031859.

- Saartok T, Dahlberg E, Gustafsson JA (June 1984). "Relative binding affinity of anabolic-androgenic steroids: comparison of the binding to the androgen receptors in skeletal muscle and in prostate, as well as to sex hormone-binding globulin". Endocrinology. 114 (6): 2100–6. doi:10.1210/endo-114-6-2100. PMID 6539197.

- Kicman AT (June 2008). "Pharmacology of anabolic steroids". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (3): 502–21. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.165. PMC 2439524. PMID 18500378.

- Schänzer W, Geyer H, Fusshöller G, Halatcheva N, Kohler M, Parr MK, Guddat S, Thomas A, Thevis M (2006). "Mass spectrometric identification and characterization of a new long-term metabolite of metandienone in human urine". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 20 (15): 2252–8. doi:10.1002/rcm.2587. PMID 16804957.

- Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 952–4.

- Fragkaki AG, Angelis YS, Tsantili-Kakoulidou A, Koupparis M, Georgakopoulos C (May 2009). "Schemes of metabolic patterns of anabolic androgenic steroids for the estimation of metabolites of designer steroids in human urine". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 115 (1–2): 44–61. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.02.016. PMID 19429460.

- US granted 2900398, Wettstein A, Hunger A, Meystre C, Ehmann L, "Process for the manufacture of steroid dehydrogenation products", issued 18 August 1959, assigned to Ciba Pharmaceutical Products, Inc.

- Chaney M (16 June 2008). "Dianabol, the first widely used steroid, turns 50". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- Peters J (2005-02-18). "The Man Behind the Juice". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- Quinn TJ (2009-02-01). "OTL: Football's first steroids team? The '63 Chargers". ESPN. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- Fourcroy J (2006). "Designer steroids: past, present and future". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 13 (3): 306–309. doi:10.1097/01.med.0000224812.46942.c3.

- Llewellyn W (2011-01-01). Anabolics. Molecular Nutrition Llc. ISBN 978-0-9828280-1-4.

- Roach R (2017-01-14). Muscle, Smoke and Mirrors. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4670-3840-9.

- Diversion Control Division. "Implementation of the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved 2017-01-14.

- Karch SB (21 December 2006). Drug Abuse Handbook (Second ed.). CRC Press. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-1-4200-0346-8.

External links