20α-Dihydroprogesterone

20α-Dihydroprogesterone (20α-DHP), also known as 20α-hydroxyprogesterone (20α-OHP), is a naturally occurring, endogenous progestogen.[1][2][3] It is a metabolite of progesterone, formed by the 20α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (20α-HSDs) AKR1C1, AKR1C2, and AKR1C3 and the 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) HSD17B1.[4][5] 20α-DHP can be transformed back into progesterone by 20α-HSDs and by the 17β-HSD HSD17B2.[6] HSD17B2 is expressed in the human endometrium.[7][8][9] In animal studies, 20α-DHP has been found to be selectively taken up into and retained in target tissues such as the uterus, brain, and skeletal muscle.[6]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

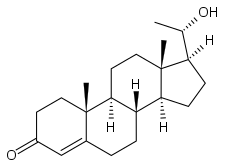

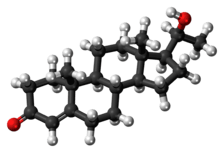

| IUPAC name

(8S,9S,10R,13S,14S,17S)-17-[(1S)-1-hydroxyethyl]-10,13-dimethyl-1,2,6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-dodecahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthren-3-one | |

| Other names

20α-DHP; 20α-Hydroxyprogesterone; 20α-OHP; 20α-Hydroxypregn-4-en-3-one; Pregn-4-en-20α-ol-3-one | |

| Identifiers | |

CAS Number |

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.137 |

| EC Number |

|

| MeSH | 20-alpha-Dihydroprogesterone |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

InChI

| |

SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

Chemical formula |

C21H32O2 |

| Molar mass | 316.478 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

20α-DHP has very low affinity for the progesterone receptor and is much less potent as a progestogen in comparison to progesterone, with about one-fifth of the relative progestogenic activity.[1][2][3][10][11][6] It has also been found to act as an aromatase inhibitor and to inhibit the production of estrogen in breast tissue in vitro.[12]

A single 200-mg oral dose of micronized progesterone has been found to result in peak levels of 20α-DHP of around 1 ng/mL after 2 hours.[13] In another study however, peak levels of 20α-DHP were around 10 ng/mL during therapy with 300 mg/day oral micronized progesterone.[14] 20α-DHP is formed from progesterone in the liver and in target tissues such as the endometrium.[14] It appears to be more slowly eliminated than progesterone.[14]

See also

- 20β-Dihydroprogesterone

- 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone

- 16α-Hydroxyprogesterone

- 5α-Dihydroprogesterone

- 11-Deoxycorticosterone

References

- Beranič N, Gobec S, Rižner TL (2011). "Progestins as inhibitors of the human 20-ketosteroid reductases, AKR1C1 and AKR1C3". Chem. Biol. Interact. 191 (1–3): 227–33. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2010.12.012. PMID 21182831.

- Tony M. Plant; Anthony J. Zeleznik (15 November 2014). Knobil and Neill's Physiology of Reproduction: Two-Volume Set. Academic Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-12-397769-4.

- Cynthia L. Darlington (27 April 2009). The Female Brain. CRC Press. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-4200-7745-2.

- Marianne J. Legato (29 October 2009). Principles of Gender-Specific Medicine. Academic Press. pp. 617–. ISBN 978-0-08-092150-1.

- Rižner TL, Penning TM (January 2014). "Role of aldo-keto reductase family 1 (AKR1) enzymes in human steroid metabolism". Steroids. 79: 49–63. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2013.10.012. PMC 3870468. PMID 24189185.

- Nowak FV (April 2002). "Distribution and metabolism of 20 alpha-hydroxylated progestins in the female rat". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 80 (4–5): 469–79. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(02)00039-0. PMID 11983494.

- Casey ML, MacDonald PC, Andersson S (November 1994). "17 beta-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2: chromosomal assignment and progestin regulation of gene expression in human endometrium". J. Clin. Invest. 94 (5): 2135–41. doi:10.1172/JCI117569. PMC 294662. PMID 7962560.

- Lora Hedrick Ellenson (1 December 2016). Molecular Genetics of Endometrial Carcinoma. Springer. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-3-319-43139-0.

- Byrns MC (January 2014). "Regulation of progesterone signaling during pregnancy: implications for the use of progestins for the prevention of preterm birth". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 139: 173–81. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.01.015. PMID 23410596.

- Bertram G. Katzung (30 November 2017). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology 14th Edition. McGraw-Hill Education. p. 728. ISBN 978-1-259-64116-9.

In addition to progesterone, 20α- and 20β-hydroxyprogesterone (20α- and 20β-hydroxy-4-pregnene-3-one) also are found. These compounds have about one-fifth the progestational activity of progesterone in humans and other species.

- Ogle TF, Beyer BK (February 1982). "Steroid-binding specificity of the progesterone receptor from rat placenta". J. Steroid Biochem. 16 (2): 147–50. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(82)90160-1. PMID 7078152.

- Pasqualini JR, Chetrite G (2008). "The anti-aromatase effect of progesterone and of its natural metabolites 20alpha- and 5alpha-dihydroprogesterone in the MCF-7aro breast cancer cell line". Anticancer Res. 28 (4B): 2129–33. PMID 18751385.

- Sitruk-Ware R, Bricaire C, De Lignieres B, Yaneva H, Mauvais-Jarvis P (October 1987). "Oral micronized progesterone. Bioavailability pharmacokinetics, pharmacological and therapeutic implications--a review". Contraception. 36 (4): 373–402. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(87)90088-6. PMID 3327648.

- Padwick ML, Endacott J, Matson C, Whitehead MI (September 1986). "Absorption and metabolism of oral progesterone when administered twice daily". Fertil. Steril. 46 (3): 402–7. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)49576-2. PMID 3743792.