Thalidomide

Thalidomide, sold under the brand name Thalomid among others, is a medication used to treat a number of cancers including multiple myeloma, graft-versus-host disease, and a number of skin conditions including complications of leprosy.[3] While it has been used in a number of HIV associated conditions, such use is associated with increased levels of the virus.[3] It is taken by mouth.[3]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /θəˈlɪdəmaɪd/[1] |

| Trade names | Contergan, Thalomid, Talidex, others |

| Other names | α-Phthalimidoglutarimide |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699032 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (capsules) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 90% |

| Protein binding | 55% and 66% for the (R)-(+)- and (S)-(−)-enantiomers, respectively[2] |

| Metabolism | Liver (minimally via CYP2C19-mediated 5-hydroxylation; mostly via non-enzymatic hydrolysis at the four amide sites)[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 5–7.5 hours (dose-dependent)[2] |

| Excretion | Urine, faeces[2] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.029 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H10N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 258.233 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Common side effects include sleepiness, rash, and dizziness.[3] Severe side effects include tumor lysis syndrome, blood clots, and peripheral neuropathy.[4] Use in pregnancy may harm the baby, including resulting in malformation of the limbs.[3] In males who are taking the medication, condoms are recommended if their partner could become pregnant.[4] It is an immunomodulatory medication and works by a number of mechanisms including stimulating T cells and decreasing TNF-α production.[3]

Thalidomide was first marketed in West Germany in 1957 where it was available over-the-counter.[5][6] It was approved for medical use in the United States in 1998.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[4] In the United Kingdom it costs the NHS about £1,194 per month as of 2018.[4] This amount in the United States costs about US$9,236 as of 2019.[8]

Initially thalidomide was promoted for anxiety, trouble sleeping, "tension", and morning sickness.[6][9] While initially deemed to be safe in pregnancy, concerns regarding birth defects were noted in 1961 and the medication was removed from the market in Europe that year.[6][5] The total number of people affected by use during pregnancy is estimated at 10,000, of which about 40% died around the time of birth.[6][3] Those who survived had limb, eye, urinary tract, and heart problems.[5] Its initial entry into the US market was prevented by Frances Kelsey at the FDA.[9] The birth defects of thalidomide led to the development of greater drug regulation and monitoring in many countries.[9][5]

Medical uses

Thalidomide is used as a first-line treatment in multiple myeloma in combination with dexamethasone or with melphalan and prednisone, to treat acute episodes of erythema nodosum leprosum, and for maintenance therapy.[10][11]

The bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB) is related to leprosy. Thalidomide may be helpful in some cases where standard TB drugs and corticosteroids are not sufficient to resolve severe inflammation in the brain.[12][13]

It is used as a second-line treatment to manage graft versus host disease and aphthous stomatitis in children and has been prescribed for other conditions in children including actinic prurigo and epidermolysis bullosa; the evidence for these uses is weak.[14] It is recommended only as a third line treatment in graft versus host disease in adults, based on lack of efficacy and side effects observed in clinical trials.[15][16]

Contraindications

Thalidomide should not be used by people who are breastfeeding or pregnant, trying or able to conceive a child, or cannot or will not follow the risk management program to prevent pregnancies. The prescribing doctor is required to ensure that contraception is being used, and regular pregnancy tests are taken. Some people are allergic to thalidomide and should not take it. It should be used with caution in people with chronic infections like HIV or hepatitis B.[11][10]

Adverse effects

Thalidomide causes birth defects.[11][10][17] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulatory agencies have approved marketing of the drug only with an auditable risk evaluation and mitigation strategy that ensures that people using the drug are aware of the risks and avoid pregnancy; this applies to both men and women, as the drug can be transmitted in semen.[17]

There is a high risk that thalidomide can cause excessive blood clots. There is also a high risk that thalidomide can interfere with formation of various kinds of new blood cells, creating a risk of infection via neutropenia, leukopenia, and lymphopenia, and risks that blood will not clot via thrombocytopenia. There is also a risk of anemia via lack of red blood cells. The drug can also damage nerves, causing peripheral neuropathy that may be irreversible.[11][10]

Thalidomide has several cardiovascular adverse effects, including risk of heart attacks, pulmonary hypertension, and changes in heart rhythm including syncope, bradycardia, and atrioventricular block.[11][10]

It can cause liver damage and severe skin reactions like Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. It tends to make people sleepy, which creates risk when driving and operating other machinery. As it kills cancer cells, it can cause tumor lysis syndrome. Thalidomide can prevent menstruation.[11][10]

Other than the above, very common (reported in more than 10% of people) adverse effects include tremor, dizziness, tingling, numbness, constipation, and peripheral edema.[11][10]

Common (reported by 1–10% of people) adverse effects include confusion, depressed mood, reduced coordination, heart failure, difficulty breathing, interstitial lung disease, lung inflammation, vomiting, dry mouth, rashes, dry skin, fever, weakness, and a sense of unwellness.[11][10]

Interactions

There are no expected pharmacokinetic interactions between thalidomide and other medicines due to its neutral effects on P-glycoprotein and the cytochrome P450 family. It may interact with sedatives due to its sedative action and bradycardic agents, like beta-blockers, due to its bradycardia-inducing effects. The risk of peripheral neuropathy may be increased by concomitant treatment with other agents known to cause peripheral neuropathy.[18] The risk of venous thromboembolisms with thalidomide seems to be increased when patients are treated with oral contraceptives or other cytotoxic agents (including doxorubicin and melphalan) concurrently. Thalidomide may interfere with various contraceptives, and hence it is advised that women of reproductive age use at least two different means of contraception to ensure that no child will be conceived while they are taking thalidomide.[18][11][10]

Overdose

As of 2013, eighteen cases of overdoses had been reported with doses of up to 14.4 grams, none of them fatal.[18] No specific antidote for overdose exists and treatment is purely supportive.[18]

Pharmacology

The precise mechanism of action for thalidomide is not known, although efforts to identify thalidomide's teratogenic action generated 2,000 research papers and the proposal of 15 or 16 plausible mechanisms by the year 2000.[19] As of 2015, the main theories were inhibition of the process of angiogenesis, its inhibition of cereblon, a ubiquitin ligase, and its ability to generate reactive oxygen species which in turn kills cells.[20][21] In 2018, results were first published which suggested that thalidomide's teratogenic effects are mediated through degradation of the transcription factor, SALL4, an as yet unverified finding.[22]

Thalidomide also binds to and acts as an antagonist of the androgen receptor (AR) and hence is a nonsteroidal antiandrogen (NSAA) of some capacity.[23] In accordance, it can produce gynecomastia and sexual dysfunction as side effects in men.[24]

Thalidomide is provided as a racemic mixture of two enantiomers; while there are reports that only one of the enantiomers may cause birth defects, the body converts each enantiomer into the other through mechanisms that are not well understood.[17]

Chemistry

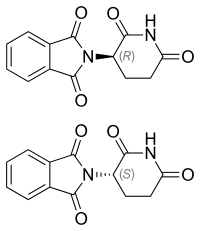

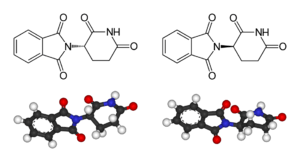

Left: (S)-(−)-thalidomide

Right: (R)-(+)-thalidomide

Thalidomide is racemic; while R-thalidomide is the bioactive form of the molecule, the individual enantiomers can racemize to each other due to the acidic hydrogen at the chiral centre, which is the carbon of the glutarimide ring bonded to the phthalimide substituent. The racemization process can occur in vivo.[2][25][26][27]

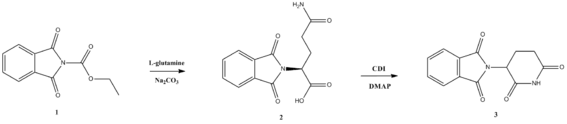

Celgene Corporation originally synthesized thalidomide using a three-step sequence starting with L-glutamic acid treatment, but this has since been reformed by the use of L-glutamine.[28] As shown in the image below, N-carbethoxyphtalimide (1) can react with L-glutamine to yield N-phthaloyl-L-glutamine (2). Cyclization of N-phthaloyl-L-glutamine occurs using carbonyldiimidazole, which then yields thalidomide (3).[28] Celgene Corporation's original method resulted in a 31% yield of S-thalidomide, whereas the two-step synthesis yields 85–93% product that is 99% pure.

History

Thalidomide was discovered by professionals at the German pharmaceutical company Chemie Grünenthal (now Grünenthal GmbH) circa 1953. The company had been established as a soap maker after World War II ended, to address the urgent market need for antibiotics. Heinrich Mueckter was appointed to head the discovery program based on his experience working with the German army's antiviral research. While preparing reagents for the work, Mueckter's assistant Wilhelm Kunz isolated a by-product that was recognized by pharmacologist Herbert Keller as an analog of glutethimide, a sedative. The medicinal chemistry work turned to improving the lead compound into a suitable drug: the result was thalidomide. The toxicity was examined in several animals, and the drug was introduced in 1956 as a sedative.[29]

Researchers at Chemie Grünenthal found that thalidomide was a particularly effective antiemetic that had an inhibitory effect on morning sickness.[30] On October 1, 1957, the company launched thalidomide and began marketing it under the trade name Contergan.[31][32] It was proclaimed a "wonder drug" for insomnia, coughs, colds and headaches.

During this period, the use of medications during pregnancy was not strictly controlled, and drugs were not thoroughly tested for potential harm to the fetus.[30] Thousands of pregnant women took the drug to relieve their symptoms. At the time of the drug's development, scientists did not believe any drug taken by a pregnant woman could pass across the placental barrier and harm the developing fetus,[33] even though the effect of alcohol on fetal development had been documented by case studies on alcoholic mothers since at least 1957.[34] There soon appeared reports of abnormalities in children being born to mothers using thalidomide. In late 1959, it was noticed that peripheral neuritis developed in patients who took the drug over a period of time, and it was only after this point that thalidomide ceased to be provided over the counter.[35]

While initially considered safe, the drug was responsible for teratogenic deformities in children born after their mothers used it during pregnancies, prior to the third trimester. In November 1961, thalidomide was taken off the market due to massive pressure from the press and public.[36] Experts estimate that the drug thalidomide led to the death of approximately 2,000 children and serious birth defects in more than 10,000 children, about 5,000 of them in West Germany. The regulatory authorities in East Germany did not approve thalidomide.[37] One reason for the initially unobserved side effects of the drug and the subsequent approval in West Germany was that at that time drugs did not have to be tested for teratogenic effects. They had been tested on rodents only, as was usual at the time.[38]

In the UK, the British pharmaceutical company The Distillers Company (Biochemicals) Ltd, a subsidiary of Distillers Co. Ltd (now part of Diageo plc), marketed thalidomide under the brand name Distaval as a remedy for morning sickness throughout the UK, Australia and New Zealand. Their advertisement claimed that "Distaval can be given with complete safety to pregnant women and nursing mothers without adverse effect on mother or child...Outstandingly safe Distaval has been prescribed for nearly three years in this country."[37] Globally, more pharmaceutical companies started to produce and market the drug under license from Chemie Grünenthal. By the mid-1950s, 14 pharmaceutical companies were marketing thalidomide in 46 countries under at least 37 different trade names.

In the US, representatives from Chemie Grünenthal approached Smith, Kline & French (SKF), now GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), with a request to market and distribute the drug in North America. A memorandum rediscovered in 2010 in the archives of the FDA shows that, as part of its in-licensing approach, Smith, Kline and French conducted animal tests and ran a clinical trial of the drug in the US involving 875 people, including pregnant women, in 1956–57. In 1956, researchers at SKF involved in clinical trials noted that even when used in very high doses, thalidomide could not induce sleep in mice. And when administered at doses 50 to 650 times larger than that claimed by Chemie Grünenthal to be "sleep inducing", the researchers could still not achieve the hypnotic effect in animals that it had on humans. After completion of the trial, and based on reasons kept hidden for decades, SKF declined to commercialize the drug. Later, Chemie Grünenthal, in 1958, reached an agreement with William S Merrell Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, (later Richardson-Merrell, now part of Sanofi), to market and distribute thalidomide throughout the US[37]

The US FDA refused to approve thalidomide for marketing and distribution. However, the drug was distributed in large quantities for testing purposes, after the American distributor and manufacturer Richardson-Merrell had applied for its approval in September 1960. The official in charge of the FDA review, Frances Oldham Kelsey, did not rely on information from the company, which did not include any test results. Richardson-Merrell was called on to perform tests and report the results. The company demanded approval six times, and was refused each time. Nevertheless, a total of 17 children with thalidomide-induced malformations were born in the US. Oldham Kelsey was given a Presidential award for distinguished service from the federal government for not allowing thalidomide to be approved for sale in the US.[39]

In Canada, the history of the drug thalidomide dates back to April 1, 1961. There were many different forms sold, with the most common variant being Talimol.[40] Two months after Talimol went on sale, pharmaceutical companies sent physicians letters warning about the risk of birth defects.[40] It was not until March 2, 1962, that both drugs were banned from the Canadian market by the FDD, and soon afterward physicians were warned to destroy their supplies.[40]

Leprosy treatment

In 1964, Israeli physician Jacob Sheskin administered thalidomide to a patient critically ill with leprosy. The patient exhibited erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), a painful skin condition, one of the complications of leprosy. This was attempted despite the ban on thalidomide's use, but results were favourable: the patient slept for hours and was able to get out of bed without aid upon awakening. A clinical trial studying the use of thalidomide in leprosy soon followed.[41]

Thalidomide has been used by Brazilian physicians as the drug of choice for the treatment of severe ENL since 1965, and by 1996, at least 33 cases of thalidomide embryopathy were recorded in people born in Brazil after 1965.[42] Since 1994, the production, dispensing, and prescription of thalidomide have been strictly controlled, requiring women to use two forms of birth control and submit to regular pregnancy tests. Despite this, cases of thalidomide embryopathy continue,[43][44] with at least 100 cases identified in Brazil between 2005 and 2010.[45] 5.8 million thalidomide pills were distributed throughout Brazil in this time period, largely to poor Brazilians in areas with poor access to healthcare, and these cases have occurred despite the controls.

In 1998, the FDA approved the drug's use in the treatment of ENL.[46] Because of thalidomide's potential for causing birth defects, the drug may be distributed only under tightly controlled conditions. The FDA required that Celgene Corporation, which planned to market thalidomide under the brand name Thalomid, establish a system for thalidomide education and prescribing safety (STEPS) oversight program. The conditions required under the program include limiting prescription and dispensing rights to authorized prescribers and pharmacies only, keeping a registry of all patients prescribed thalidomide, providing extensive patient education about the risks associated with the drug, and providing periodic pregnancy tests for women who take the drug.[46]

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that it did not recommend thalidomide for leprosy due to the difficulty of adequately controlling its use, and due to the availability of clofazimine.[47]

Cancer treatment

Shortly after the teratogenic properties of thalidomide were recognized in the mid-1960s, its anti-cancer potential was explored and two clinical trials were conducted in people with advanced cancer, including some people with multiple myeloma; the trials were inconclusive.[48]

Little further work was done with thalidomide in cancer until the 1990s.[48]

Judah Folkman pioneered studies into the role of angiogenesis (the proliferation and growth of blood vessels) in the development of cancer, and in the early 1970s had shown that solid tumors could not expand without it.[49][50] In 1993 he surprised the scientific world by hypothesizing the same was true of blood cancers,[51] and the next year he published work showing that a biomarker of angiogenesis was higher in all people with cancer, but especially high in people with blood cancers, and other evidence emerged as well.[52] Meanwhile, a member of his lab, Robert D'Amato, who was looking for angiogenesis inhibitors, discovered in 1994 that thalidomide inhibited angiogenesis[53] and was effective in suppressing tumor growth in rabbits.[54] Around that time, the wife of a man who was dying of multiple myeloma and whom standard treatments had failed, called Folkman asking him about his anti-angiogenesis ideas.[50] Folkman persuaded the patient's doctor to try thalidomide, and that doctor conducted a clinical trial of thalidomide for people with multiple myeloma in which about a third of the subjects responded to the treatment.[50] The results of that trial were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1999.[50][55]

After further work was done by Celgene and others, in 2006 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval for thalidomide in combination with dexamethasone for the treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients.[50][56]

Society and culture

Birth defect crisis

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, more than 10,000 children in 46 countries were born with deformities, such as phocomelia, as a consequence of thalidomide use.[57] The severity and location of the deformities depended on how many days into the pregnancy the mother was before beginning treatment; thalidomide taken on the 20th day of pregnancy caused central brain damage, day 21 would damage the eyes, day 22 the ears and face, day 24 the arms, and leg damage would occur if taken up to day 28. Thalidomide did not damage the fetus if taken after 42 days gestation.[36]

It is not known exactly how many worldwide victims of the drug there have been, although estimates range from 10,000 to 20,000.[58] Despite the side effects, thalidomide was sold in pharmacies in Canada until 1962.[40][59]

.jpg)

In the UK, the drug was licensed in 1958 and withdrawn in 1961. Of the approximately 2,000 babies born with defects, around half died within a few months and 466 survived to at least 2010.[60]

In Spain, thalidomide was widely available throughout the 1970s, perhaps even into the 1980s. There were two reasons for this. First, state controls and safeguarding were poor; indeed, it was not until 2008 that the government even admitted the country had ever imported thalidomide. Second, Grünenthal failed to insist that its sister company in Madrid warn Spanish doctors, and permitted it to not warn them. The Spanish advocacy group for victims of thalidomide estimates that in 2015, there were 250–300 living victims of thalidomide in Spain.[61]

Although the Australian obstetrician William McBride took credit for raising the alarm about thalidomide, it was a midwife called Sister Pat Sparrow who first suspected the drug was causing birth defects in the babies of patients under McBride's care at Crown Street Women's Hospital in Sydney.[62] German paediatrician Widukind Lenz, who also suspected the link, is credited with conducting the scientific research that proved thalidomide was causing birth defects in 1961.[63][64] McBride was later awarded a number of honors, including a medal and prize money by L'Institut de la Vie in Paris,[65] but he was eventually struck off the Australian medical register in 1993 for scientific fraud related to work on Debendox.[62][66] Further animal tests were conducted by Dr George Somers, Chief Pharmacologist of Distillers Company in Britain, which showed foetal abnormalities in rabbits.[67] Similar results were also published showing these effects in rats[68][69] and other species.[70]

In East Germany, the head of the central pharmacy control commission, Friedrich Jung, suspected an antivitaminic effect of thalidomide as derivative of glutamic acid.[71] Meanwhile, in West Germany, it took some time before the increase in dysmelia at the end of the 1950s was connected with thalidomide. In 1958, Karl Beck, a former pediatric doctor in Bayreuth, wrote an article in a local newspaper claiming a relationship between nuclear weapons testing and cases of dysmelia in children.[72] Based on this, FDP whip Erich Mende requested an official statement from the federal government.[72] For statistical reasons, the main data series used to research dysmelia cases started by chance at the same time as the approval date for thalidomide.[72] After the Nazi regime with its Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring used mandatory statistical monitoring to commit various crimes, western Germany had been very reluctant to monitor congenital disorders in a similarly strict way.[73] The parliamentary report rejected any relation with radioactivity and the abnormal increase of dysmelia.[72] Also the DFG research project installed after the Mende request was not helpful. The project was led by pathologist Franz Büchner, who ran the project to propagate his teratological theory. Büchner saw lack of healthy nutrition and behavior of the mothers as being more important than genetic reasons.[73] Furthermore, it took a while to install a Surgeon General in Germany; the Federal Ministry of Health was not founded until 1962, some months after thalidomide was banned from the market.[72] In Germany approximately 2,500 thalidomide babies were born.[64]

Several countries either restricted the drug's use or never approved it. Ingeborg Eichler, a member of the Austrian pharmaceutical admission conference, enforced thalidomide (tradename Softenon) being sold under the rules of prescription medication and as a result relatively few affected children were born in Austria and Switzerland.[74]

In the U.S., the FDA refused approval to market thalidomide, saying further studies were needed. This reduced the impact of thalidomide in U.S. patients. The refusal was largely due to pharmacologist Frances Oldham Kelsey who withstood pressure from the Richardson-Merrell Pharmaceuticals Co. She subsequently was given a distinguished service award by President John F. Kennedy.[57] Although thalidomide was never approved for sale in the United States at the time, over 2.5 million tablets had been distributed to over 1,000 physicians during a clinical testing program. It is estimated that nearly 20,000 patients, several hundred of whom were pregnant women, were given the drug to help alleviate morning sickness or as a sedative, and at least 17 children were consequently born in the United States with thalidomide-associated deformities.[75][76] While pregnant, children's television host Sherri Finkbine took over-the-counter sedative her husband had purchased in Europe.[77] When she learned that thalidomide was causing fetal deformities she wanted to abort her pregnancy, but the laws of Arizona allowed abortion only if the mother's life was in danger. Finkbine traveled to Sweden to have the abortion. Thalidomide was found to have deformed the fetus.[75]

Aftermath of scandal

The numerous reports of malformations in babies brought about the awareness of the side effects of the drug on pregnant women. The birth defects caused by the drug thalidomide can range from moderate malformation to more severe forms. Possible birth defects include phocomelia, dysmelia, amelia, bone hypoplasticity, and other congenital defects affecting the ear, heart, or internal organs.[30] Franks et al. looked at how the drug affected newborn babies, the severity of their deformities, and reviewed the drug in its early years. Webb in 1963 also reviewed the history of the drug and the different forms of birth defects it had caused. "The most common form of birth defects from thalidomide is shortened limbs, with the arms being more frequently affected. This syndrome is the presence of deformities of the long bones of the limbs resulting in shortening and other abnormalities."[40]

Germany

In 1968, a large criminal trial began in Germany, charging several Grünenthal officials with negligent homicide and injury. After Grünenthal settled with the victims in April 1970, the trial ended in December 1970 with no finding of guilt. As part of the settlement, Grünenthal paid 100 million DM into a special foundation; the German government added 320 million DM. The foundation paid victims a one-time sum of 2,500-25,000 DM (depending on severity of disability) and a monthly stipend of 100-450 DM. The monthly stipends have since been raised substantially and are now paid entirely by the government (as the foundation had run out of money). Grünenthal paid another €50 million into the foundation in 2008.

On 31 August 2012, Grünenthal chief executive Harald F. Stock who served as the Chief Executive Officer of Grünenthal GmbH from January 2009 to May 28, 2013 and was also a Member of Executive Board until 28 May 2013, apologized for the first time for producing the drug and remaining silent about the birth defects.[78] At a ceremony, Stock unveiled a statue of a disabled child to symbolize those harmed by thalidomide and apologized for not trying to reach out to victims for over 50 years. At the time of the apology, there were 5,000 to 6,000 sufferers still alive. Victim advocates called the apology "insulting" and "too little, too late", and criticized the company for not compensating victims. They also criticized the company for their claim that no one could have known the harm the drug caused, arguing that there were plenty of red flags at the time.[79]

United Kingdom

In 1968, after a long campaign by The Sunday Times, a compensation settlement for the UK victims was reached with Distillers Company (now part of Diageo), which had distributed the drug in the UK.[80][81] This compensation, which is distributed by the Thalidomide Trust in the UK, was substantially increased by Diageo in 2005.[82] The UK Government gave survivors a grant of £20 million, to be distributed through the Thalidomide Trust, in December 2009.[83]

Australia

Melbourne woman Lynette Rowe, who was born without limbs, led an Australian class action lawsuit against the drug's manufacturer, Grünenthal, which fought to have the case heard in Germany. The Supreme Court of Victoria dismissed Grünenthal's application in 2012, and the case was heard in Australia.[84] On 17 July 2012, Rowe was awarded an out-of-court settlement, believed to be in the millions of dollars and paving the way for class action victims to receive further compensation.[85] In February 2014, the Supreme Court of Victoria endorsed the settlement of $89 million AUD to 107 victims of the drug in Australia and New Zealand.[86][87]

Canada

The drug thalidomide's birth defects in children affected many people's lives, and from these events came the formation of the group called The Thalidomide Victims Association of Canada, a group of 120 Canadian survivors.[88][89] Their goal was to prevent future usage of drugs that could be of potential harm to mothers and babies. The members from the thalidomide victims association were involved in the STEPS program, which aimed to prevent teratogenicity.[30]

The effects of thalidomide increased fears regarding the safety of pharmaceutical drugs. The Society of Toxicology of Canada was formed after the effects of thalidomide were made public, focusing on toxicology as a discipline separate from pharmacology.[90] The need for the testing and approval of the toxins in certain pharmaceutical drugs became more important after the disaster. The Society of Toxicology of Canada is responsible for the Conservation Environment Protection Act, focusing on researching the impact to human health of chemical substances.[90] Thalidomide brought on changes in the way drugs are tested, what type of drugs are used during pregnancy, and increased the awareness of potential side effects of drugs.

According to Canadian news magazine program W5, most, but not all, victims of thalidomide receive annual benefits as compensation from the Government of Canada. Excluded are those who cannot provide the documentation the government requires.[91]

United States

For denying the application despite the pressure from Richardson-Merrell Pharmaceuticals Co., Kelsey eventually received the President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service at a 1962 ceremony with President John F. Kennedy. In September 2010, the FDA honored Kelsey with the first Kelsey award, given annually to an FDA staff member. This came 50 years after Kelsey, then a new medical officer at the agency, first reviewed the application from the William S. Merrell Pharmaceuticals Company of Cincinnati.[92]

Cardiologist Helen B. Taussig learned of the damaging effects of the drug thalidomide on newborns and in 1967, testified before Congress on this matter after a trip to Germany where she worked with infants with phocomelia (severe limb deformities). As a result of her efforts, thalidomide was banned in the United States and Europe.

Notable cases

- Lorraine Mercer MBE of the United Kingdom, born with phocomelia of both arms and legs, is the only thalidomide survivor to carry the Olympic Torch.[93]

- Thomas Quasthoff, an internationally acclaimed bass-baritone, who describes himself: "1.34 meters tall, short arms, seven fingers — four right, three left — large, relatively well-formed head, brown eyes, distinctive lips; profession: singer".[94]

- Niko von Glasow produced a documentary called NoBody's Perfect, based on the lives of 12 people affected by the drug, which was released in 2008.[95][96]

- Mercédes Benegbi, born with phocomelia of both arms, drove the successful campaign for compensation from her government for Canadians who were affected by thalidomide.[97]

- Mat Fraser, born with phocomelia of both arms, is an English rock musician, actor, writer and performance artist. He produced a 2002 television documentary "Born Freak", which looked at this historical tradition and its relevance to modern disabled performers. This work has become the subject of academic analysis in the field of disability studies.[98]

Change in drug regulations

The disaster prompted many countries to introduce tougher rules for the testing and licensing of drugs, such as the Kefauver Harris Amendment[99] (U.S.), Directive 65/65/EEC1 (E.U.),[100] and the Medicines Act 1968 (UK).[101][102] In the United States, the new regulations strengthened the FDA, among other ways, by requiring applicants to prove efficacy and to disclose all side effects encountered in testing.[57] The FDA subsequently initiated the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation to reclassify drugs already on the market.

Quality of life

In the 1960s, thalidomide was successfully marketed as a safer alternative to barbiturates. Due to a successful marketing campaign, thalidomide was widely used by pregnant women during the first trimester of pregnancy. However, thalidomide is a teratogenic substance, and a proportion of children born during the 1960s were afflicted with a syndrome known as thalidomide embryopathy (TE).[103] Of these babies born with TE, "about 40% of them died before their first birthday".[104] The surviving individuals are now middle-aged and they report experiencing challenges (physical, psychological, and socioeconomic) related to TE.

Individuals born with TE frequently experience a wide variety of health problems secondary to their TE. These health conditions include both physical and psychological conditions. When compared to individuals of similar demographic profiles, those born with TE report less satisfaction with their quality of life and their overall health.[103] Access to health care services can also be a challenge for these people, and women in particular have experienced difficulty in locating healthcare professionals who can understand and embrace their needs.[105]

Brand names

Brand names include Contergan, Thalomid, Talidex, Talizer, Neurosedyn, Distaval and many others.

Research

Research efforts have been focused on determining how thalidomide causes birth defects and its other activities in the human body, efforts to develop safer analogs, and efforts to find further uses for thalidomide.

Thalidomide analogs

The exploration of the antiangiogenic and immunomodulatory activities of thalidomide has led to the study and creation of thalidomide analogs.[106][107] Celgene has sponsored numerous clinical trials with analogues to thalidomide, such as lenalidomide, that are substantially more powerful and have fewer side effects — except for greater myelosuppression.[108] In 2005, Celgene received FDA approval for lenalidomide (Revlimid) as the first commercially useful derivative. Revlimid is available only in a restricted distribution setting to avoid its use during pregnancy. Further studies are being conducted to find safer compounds with useful qualities. Another more potent analog, pomalidomide, is now FDA approved.[109] Additionally, apremilast was approved by the FDA in March 2014. These thalidomide analogs can be used to treat different diseases, or used in a regimen to fight two conditions.[110]

Interest turned to pomalidomide, a derivative of thalidomide marketed by Celgene. It is a very active anti-angiogenic agent [107] and also acts as an immunomodulator. Pomalidomide was approved in February 2013 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a treatment for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma.[111] It received a similar approval from the European Commission in August 2013, and is expected to be marketed in Europe under the brand name Imnovid.[112]

Clinical research

There is no conclusive evidence that thalidomide or lenalidomide is useful to bring about or maintain remission in Crohn's disease.[113][114]

Thalidomide was studied in a Phase II trial for Kaposi's sarcoma, a rare soft-tissue cancer most commonly seen in the immunocompromised, that is caused by the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV).[115][30]

- AIDS wasting syndrome,[116] associated diarrhoea[117]

- Renal cell carcinoma (RCC)[30][118]

- Glioblastoma multiforme[30]

- Prostate cancer[30]

- Melanoma[30]

- Colorectal cancer[30]

- Crohn's disease[30]

- Rheumatoid arthritis[30]

- Behcet's syndrome[119]

- Breast cancer[30]

- Head and neck cancer[30]

- Ovarian cancer[30]

- Chronic heart failure[30]

- Graft-versus-host disease[30]

- Tuberculous meningitis[120]

See also

- Pharmacovigilance

- Immunomodulatory drug

- Discovery and development of thalidomide and its analogs

- Drug of last resort

- Health crisis

- Holt-Oram syndrome

- Category:People with phocomelia

- Diethylstilbestrol

References

- "Thalidomide". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Teo SK, Colburn WA, Tracewell WG, Kook KA, Stirling DI, Jaworsky MS, Scheffler MA, Thomas SD, Laskin OL (2004). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of thalidomide". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 43 (5): 311–27. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443050-00004. PMID 15080764.

- "Thalidomide Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 936. ISBN 9780857113382.

- Cuthbert, Alan (2003). The Oxford Companion to the Body. Oxford University Press. p. 682. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198524038.001.0001. ISBN 9780198524038.

- Miller, Marylin T. (1991). "Thalidomide Embryopathy: A Model for the Study of Congenital Incomitant Horizontal Strabismus". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 81: 623–674. PMID 1808819.

- "World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019". 2019. hdl:10665/325771. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Thalomid Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Loue, Sana; Sajatovic, Martha (2004). Encyclopedia of Women's Health. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 644. ISBN 9780306480737.

- "Thalidomide Celgene 50 mg Hard Capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. January 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "US Thalomid label" (PDF). FDA. January 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017. For label updates see FDA index page for NDA 020785

- Buonsenso D, Serranti D, Valentini P (October 2010). "Management of central nervous system tuberculosis in children: light and shade" (PDF). European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 14 (10): 845–53. PMID 21222370. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-18.

- van Toorn R, Solomons R (March 2014). "Update on the diagnosis and management of tuberculous meningitis in children". Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 21 (1): 12–8. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2014.01.006. PMID 24655399.

- Yang CS, Kim C, Antaya RJ (April 2015). "Review of thalidomide use in the pediatric population". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 72 (4): 703–11. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.01.002. PMID 25617013.

- Wolff D, Gerbitz A, Ayuk F, Kiani A, Hildebrandt GC, Vogelsang GB, Elad S, Lawitschka A, Socie G, Pavletic SZ, Holler E, Greinix H (December 2010). "Consensus conference on clinical practice in chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD): first-line and topical treatment of chronic GVHD". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 16 (12): 1611–28. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.06.015. PMID 20601036.

- Wolff D, Schleuning M, von Harsdorf S, Bacher U, Gerbitz A, Stadler M, Ayuk F, Kiani A, Schwerdtfeger R, Vogelsang GB, Kobbe G, Gramatzki M, Lawitschka A, Mohty M, Pavletic SZ, Greinix H, Holler E (January 2011). "Consensus Conference on Clinical Practice in Chronic GVHD: Second-Line Treatment of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 17 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.011. PMID 20685255.

- Smith SW (July 2009). "Chiral toxicology: it's the same thing...only different". Toxicological Sciences. 110 (1): 4–30. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp097. PMID 19414517.

- "THALOMID® CAPSULES" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Celgene Pty Limited. 21 June 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- Stephens TD, Bunde CJ, Fillmore BJ (June 2000). "Mechanism of action in thalidomide teratogenesis". Biochemical Pharmacology. 59 (12): 1489–99. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00388-3. PMID 10799645.

- Vargesson N (June 2015). "Thalidomide-induced teratogenesis: history and mechanisms". Birth Defects Research. Part C, Embryo Today. 105 (2): 140–56. doi:10.1002/bdrc.21096. PMC 4737249. PMID 26043938.

- Kim JH, Scialli AR (July 2011). "Thalidomide: the tragedy of birth defects and the effective treatment of disease". Toxicological Sciences. 122 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfr088. PMID 21507989.

- Donovan KA, An J, Nowak RP, Yuan JC, Fink EC, Berry BC, Ebert BL, Fischer ES (1 August 2018). "Thalidomide promotes degradation of SALL4, a transcription factor implicated in Duane Radial Ray Syndrome". eLife. 7. doi:10.7554/eLife.38430. PMC 6156078. PMID 30067223.

- Liu B, Su L, Geng J, Liu J, Zhao G (October 2010). "Developments in nonsteroidal antiandrogens targeting the androgen receptor". ChemMedChem. 5 (10): 1651–61. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201000259. PMID 20853390.

- Nuttall FQ, Warrier RS, Gannon MC (May 2015). "Gynecomastia and drugs: a critical evaluation of the literature". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 71 (5): 569–78. doi:10.1007/s00228-015-1835-x. PMC 4412434. PMID 25827472.

- Eriksson T, Björkman S, Roth B, Fyge A, Höglund P (1995). "Stereospecific determination, chiral inversion in vitro and pharmacokinetics in humans of the enantiomers of thalidomide". Chirality. 7 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1002/chir.530070109. PMID 7702998.

- Man HW, Corral LG, Stirling DI, Muller GW (October 2003). "Alpha-fluoro-substituted thalidomide analogues". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 13 (20): 3415–7. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00778-9. PMID 14505639.

- Bartlett JB, Dredge K, Dalgleish AG (April 2004). "The evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agents". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 4 (4): 314–22. doi:10.1038/nrc1323. PMID 15057291.

- Muller G, Konnecke W, Smith A, Khetani V (19 March 1999). "A Concise Two-Step Synthesis of Thalidomide". Organic Process Research & Development. 3 (2): 139–140. doi:10.1021/op980201b.

- Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug discovery : a history (Rev. and updated ed.). Chichester: Wiley. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- Franks ME, Macpherson GR, Figg WD (May 2004). "Thalidomide". Lancet. 363 (9423): 1802–11. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16308-3. PMID 15172781.

- Grünenthal: Where we come from. Official website, undated. Retrieved 2 July 2018. See also Developments regarding thalidomide

- Moghe VV, Kulkarni U, Parmar UI (2008). "Thalidomide" (PDF). Bombay Hospital Journal. Bombay: Bombay Hospital. 50 (3): 472–6.

- Heaton, C. A. (1994). The Chemical Industry. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7514-0018-2.

- See Rouquette (1957) cited by Landesman-Dwyer S (1982). "Maternal drinking and pregnancy outcome". Applied Research in Mental Retardation. 3 (3): 241–63. doi:10.1016/0270-3092(82)90018-2. PMID 7149705.

- Kelsey FO (1967). "Events after thalidomide". Journal of Dental Research. 46 (6): 1201–5. doi:10.1177/00220345670460061201. PMID 5235007.

- "Thalidomide: The Fifty Year Fight (no longer available)". BBC. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- Hofland P. "Reversal of Fortune: How a Vilified Drug Became a Life-saving Agent in the "War" Against Cancer". Onco'Zine.

- VFA: teratogenic effects 6. July 2011.

- "Report". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 12 May 2009. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009.

- Webb JF (November 1963). "Canadian Thalidomide Experience". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 89: 987–92. PMC 1921912. PMID 14076167.

- Silverman WA (August 2002). "The schizophrenic career of a "monster drug"". Pediatrics. 110 (2 Pt 1): 404–6. doi:10.1542/peds.110.2.404. PMID 12165600.

- Castilla EE, Ashton-Prolla P, Barreda-Mejia E, Brunoni D, Cavalcanti DP, Correa-Neto J, Delgadillo JL, Dutra MG, Felix T, Giraldo A, Juarez N, Lopez-Camelo JS, Nazer J, Orioli IM, Paz JE, Pessoto MA, Pina-Neto JM, Quadrelli R, Rittler M, Rueda S, Saltos M, Sánchez O, Schüler L (December 1996). "Thalidomide, a current teratogen in South America". Teratology. 54 (6): 273–7. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199702)55:2<156::AID-TERA6>3.0.CO;2-1. PMID 9098920.

- Paumgartten FJ, Chahoud I (July 2006). "Thalidomide embryopathy cases in Brazil after 1965". Reproductive Toxicology. 22 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.11.007. PMID 16427249.

- Braziliense C (January 2006). "Talidomida volta a assustar" [Thalidomide again scare] (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Crawford A (23 July 2013). "Brazil's new generation of Thalidomide babies". BBC News.

- Stolberg SG (17 July 1998). "Thalidomide Approved to Treat Leprosy, With Other Uses Seen". New York Times. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- Anon. "Use of thalidomide in leprosy". WHO:leprosy elimination. WHO. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV (March 2008). "Multiple myeloma". Blood. 111 (6): 2962–72. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-10-078022. PMC 2265446. PMID 18332230.

- Donahoe PK (2014). "Judah Folkman: 1933–2008. A Biographical Memoir" (PDF). National Academy of Sciences.

- Bielenberg DR, D'Amore PA (2008). "Judah Folkman's contribution to the inhibition of angiogenesis". Lymphatic Research and Biology. 6 (3–4): 203–7. doi:10.1089/lrb.2008.1016. PMID 19093793.

- Folkman J (December 2001). "Angiogenesis-dependent diseases". Seminars in Oncology. 28 (6): 536–42. doi:10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90021-1. PMID 11740806.

- Ribatti D (2008). "Judah Folkman, a pioneer in the study of angiogenesis". Angiogenesis. 11 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1007/s10456-008-9092-6. PMC 2268723. PMID 18247146.

- D'Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J (April 1994). "Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 91 (9): 4082–4085. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.9.4082. PMC 43727. PMID 7513432.

- Verheul HM, Panigrahy D, Yuan J, D'Amato RJ (January 1999). "Combination oral antiangiogenic therapy with thalidomide and sulindac inhibits tumour growth in rabbits". Br J Cancer. 79 (1): 114–118. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6690020. PMC 2362163. PMID 10408702.

- Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, Ayers D, Roberson P, Eddlemon P, Munshi N, Anaissie E, Wilson C, Dhodapkar M, Zeddis J, Barlogie B (November 1999). "Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma". The New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (21): 1565–71. doi:10.1056/NEJM199911183412102. PMID 10564685.

- "FDA Approval for Thalidomide". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- Bren L (28 February 2001). "Frances Oldham Kelsey: FDA Medical Reviewer Leaves Her Mark on History". FDA Consumer. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Zimmer C (15 March 2010). "Answers Begin to Emerge on How Thalidomide Caused Defects". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

As they report in the current issue of Science, a protein known as cereblon latched on tightly to the thalidomide

- "Turning Points of History–Prescription for Disaster". History Television. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- "Apology for thalidomide survivors". BBC News. 14 January 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- Scott C, Haupt O (3 May 2015). "The forgotten victims". The Sunday Times Magazine. pp. 12–19. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- Swan, Norman (28 June 2018). "Dr William McBride: The Flawed Character Credited with Linking Thalidomide to Birth Defects." ABC.net.au. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- Anon. "Widukind Lenz". who name it?. Ole Daniel Enersen. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- Anon (7 June 2002). "Thalidomide:40 years on". BBC news. BBC. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- "Report of Thalidomide at University of New South Wales". Embryology.med.unsw.edu.au. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Millikin, Robert (20 February 1993). "'Thalidomide Doctor' Guilty of Medical Fraud: William McBride, Who Exposed the Danger of One Anti-Nausea Drug, Has Been Disgraced by Experiments with Another." The Independent. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Somers GF (1963). "The foetal toxicity of thalidomide". Proc. European Soc. Study Drug Toxicity. 1: 49.

- King C, Kendrick F (1962). "Teratogenic effects of thalidomide in the Sprague Dawley rat". The Lancet. 280 (7265): 409–17. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(62)90822-X. PMID 14288814.

- McColl JD, Globus M, Robinson S (1965). "Effect of some therapeutic agents on the developing rat fetus". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 7 (7265): 409–17. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(62)90822-X. PMID 14288814.

- Botting J (April 2015). "Chapter 18". Animals and Medicine: The Contribution of Animal Experiments to the Control of Disease. OpenBook Publishers. ISBN 9781783741175. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- "DDR-Bürger schliefen ohne Contergan" [East German citizens slept without thalidomide]. Neues Deutschland (in German). 4 November 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- Thomann K (2007). "Die Contergan-Katastrophe: Die trügerische Sicherheit der "harten" Daten" [The thalidomide disaster: The false security of 'hard' data]. Deutsches Ärzteblatt (in German). 104 (41): A–2778 / B–2454 / C–2382. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- Zichner L, Rauschmann MA, Thomann KD (2005). Die Contergankatastrophe eine Bilanz nach 40 Jahren [The thalidomide catastrophe takes stock after 40 years] (in German). Darmstadt: Steinkopff. ISBN 978-3-7985-1479-9.

- "10.000 Fälle von Missbildungen" [10,000 cases of malformations] (in German). ORF. Archived from the original on 2009-08-14. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- Braun W (29 December 2015). "Thalidomide: The Connection Between a Statue in Trafalgar Square, a 1960s Children's Show Host and the Abortion Debate". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- Mekdeci B. "Bendectin Part 1: How a Commonly Used Drug Caused Birth Defects". Archived from the original on 18 December 2013.

- "Click - Debating Reproductive Rights - Reproductive Rights and Feminism, History of Abortion Battle, History of Abortion Debate, Roe v. Wade and Feminists". www.cliohistory.org. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- "Speech on the occasion of the inauguration of Thalidomide-Memorial". Grünenthal GmbH Website. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012.

- "Thalidomide apology insulting, campaigners say". BBC News. September 1, 2012. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016.

- Ryan C (1 April 2004). "They just didn't know what it would do". BBC News:Health. BBC news. Archived from the original on 2004-07-07. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- Flintoff J (23 March 2008). "Thalidomide: the battle for compensation goes on". The Sunday Times. London: Times Newspapers Ltd. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- "Compensation offer on Thalidomide". BBC News. 7 July 2005. Archived from the original on 2009-01-20. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "Thalidomide survivors to get £20m". BBC News. 23 December 2009. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- "Australian thalidomide victims win right for hearing". ABC News. 19 December 2011.

- Petrie A (19 July 2012). "Landmark thalidomide payout offers hope for thousands". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Farnsworth S (7 February 2014). "Supreme Court formally approves $89m compensation payout for Thalidomide victims". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Australian Associated Press (7 February 2014). "Thalidomide survivors' compensation approved". The Sunday Star-Times. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- Warren R (2001). "Living in a world with thalidomide: a dose of reality". FDA Consumer. 35 (2): 40. PMID 11444250.

- "TVAC and its mission - Thalidomide". web.archive.org. June 24, 2009.

- Racz WJ, Ecobichon DJ, Baril M (August 2003). "On-line sources of toxicological information in Canada". Toxicology. 190 (1–2): 3–14. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(03)00192-6. PMID 12909394.

- "The plight of the thalidomide 'sample babies' who don't qualify for gov't compensation". W5. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Harris G (13 September 2010). "The Public's Quiet Savior From Harmful Medicines". The New York Times.

- Tamplin H (12 June 2015). "Mid Sussex residents honoured by Queen". Mid Sussex Times. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- "Orpheus lives: A small good thing in Quastoff". The Portland Phoenix. April 19, 2002. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "NoBody's Perfect (2008): Release Info". IMDB. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Brussat F, Brussat MA. "Film Review: NoBody's Perfect". Spirituality & Practice. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Outstanding eight to receive honorary doctorates at Convocation". Daily News. Windsor, Ontario, Canada: University of Windsor. 9 June 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Mitchell, David; Snyder, Sharon (Summer 2005). "Disability Studies Quarterly". Volume 25, No. 3.

- "50 Years: The Kefauver-Harris Amendments". Food and Drug Administration (United States). Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "Thalidomide". National Health Service (England). Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Conroy S, McIntyre J, Choonara I (March 1999). "Unlicensed and off label drug use in neonates". Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 80 (2): F142–4, discussion F144–5. doi:10.1136/fn.80.2.F142. PMC 1720896. PMID 10325794.

- "The evolution of pharmacy, Theme E, Level 3 Thalidomide and its aftermath" (PDF). Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2011.

- Wadman, Ruth; Atkin, Karl; Glendinning, Caroline; Newbronner, Elizabeth (2019-01-16). "The health and quality of life of Thalidomide survivors as they age – Evidence from a UK survey". PLOS ONE. 14 (1): e0210222. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210222. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6334953. PMID 30650111.

- Nippert, Irmgard; Edler, Birgit; Schmidt-Herterich, Claudia (2002). "40 years later: the health related quality of life of women affected by thalidomide". Community Genetics. 5 (4): 209–216. doi:10.1159/000066691. ISSN 1422-2795. PMID 14960874.

- Nippert, Irmgard; Edler, Birgit; Schmidt-Herterich, Claudia (2002). "40 years later: the health related quality of life of women affected by thalidomide". Community Genetics. 5 (4): 209–216. doi:10.1159/000066691. ISSN 1422-2795. PMID 14960874.

- Shah JH, Swartz GM, Papathanassiu AE, Treston AM, Fogler WE, Madsen JW, Green SJ (August 1999). "Synthesis and enantiomeric separation of 2-phthalimidino-glutaric acid analogues: potent inhibitors of tumor metastasis". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 42 (16): 3014–7. doi:10.1021/jm990083y. PMID 10447943.

- D'Amato RJ, Lentzsch S, Anderson KC, Rogers MS (December 2001). "Mechanism of action of thalidomide and 3-aminothalidomide in multiple myeloma". Seminars in Oncology. 28 (6): 597–601. doi:10.1016/S0093-7754(01)90031-4. PMID 11740816.

- Rao KV (September 2007). "Lenalidomide in the treatment of multiple myeloma". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 64 (17): 1799–807. doi:10.2146/ajhp070029. PMID 17724360.

- "Search of: pomalidomide". Clinicaltrials.gov. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Raghupathy R, Billett HH (March 2009). "Promising therapies in sickle cell disease". Cardiovascular & Hematological Disorders Drug Targets. 9 (1): 1–8. doi:10.2174/187152909787581354. PMID 19275572.

- "Pomalyst (Pomalidomide) Approved By FDA For Relapsed And Refractory Multiple Myeloma". The Myeloma Beacon. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- "Pomalidomide Approved In Europe For Relapsed And Refractory Multiple Myeloma". The Myeloma Beacon. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- Srinivasan R, Akobeng AK (April 2009). "Thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for induction of remission in Crohn's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD007350. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007350.pub2. PMID 19370684.

- Akobeng AK, Stokkers PC (April 2009). "Thalidomide and thalidomide analogues for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD007351. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007351.pub2. PMID 19370685.

- Rose LJ, Fishman AD, Sparano JA (11 March 2013). Talavera F, McKenna R, Harris JE (eds.). "Kaposi Sarcoma Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- Gordon JN, Trebble TM, Ellis RD, Duncan HD, Johns T, Goggin PM (April 2005). "Thalidomide in the treatment of cancer cachexia: a randomised placebo controlled trial". Gut. 54 (4): 540–5. doi:10.1136/gut.2004.047563. PMC 1774430. PMID 15753541.

- Sharpstone D, Rowbottom A, Francis N, Tovey G, Ellis D, Barrett M, Gazzard B (June 1997). "Thalidomide: a novel therapy for microsporidiosis". Gastroenterology. 112 (6): 1823–9. doi:10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178672. PMID 9178672.

- Tunio MA, Hashmi A, Qayyum A, Naimatullah N, Masood R (September 2012). "Low-dose thalidomide in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma". JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 62 (9): 876–9. PMID 23139966.

- Hamuryudan V, Mat C, Saip S, Ozyazgan Y, Siva A, Yurdakul S, Zwingenberger K, Yazici H (March 1998). "Thalidomide in the treatment of the mucocutaneous lesions of the Behçet syndrome. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Annals of Internal Medicine. 128 (6): 443–50. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-128-6-199803150-00004. PMID 9499327.

- Wallis RS, Hafner R (April 2015). "Advancing host-directed therapy for tuberculosis". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 15 (4): 255–63. doi:10.1038/nri3813. PMID 25765201.

Further reading

- Stephens T, Brynner R (2001-12-24). Dark Remedy: The Impact of Thalidomide and Its Revival as a Vital Medicine. Perseus Books. ISBN 978-0-7382-0590-8.

- Knightley P, Evans H (1979). Suffer The Children: The Story of Thalidomide. New York: The Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-68114-3.

External links

- WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter No. 2, 2003 – See page 11, Feature Article

- CBC Digital Archives – Thalidomide: Bitter Pills, Broken Promises

- Remind me again, what is thalidomide and how did it cause so much harm?. The Conversation, 7 December 2015