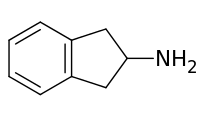

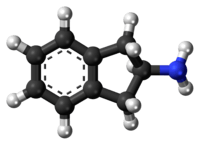

2-Aminoindane

2-Aminoindane (2-AI) is a research chemical with applications in neurologic disorders and psychotherapy that has also been sold as a designer drug.[1] It acts as a selective substrate for NET and DAT.[2][3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 2-indanylamine; 2-indanamine |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.019.111 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H11N |

| Molar mass | 133.190 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Therapeutic and illicit uses

Synthetic aminoindanes were originally developed in the context of anti-Parkinsonian drugs as a metabolite of rasagiline and as a tool to be used in psychotherapy. Deaths related to their toxic effects have been observed both in the laboratory in animal studies and in clinical encounters.[4] 2-AI is a rigid analogue of amphetamine and partially substitutes for it in rat discrimination tests.[5]

Legal status

Sweden's public health agency suggested classifying 2-AI as a hazardous substance, on June 24, 2019.[6]

Chemical derivatives

There are a number of derivatives of 2-aminoindane and its positional isomer 1-aminoindane exist, including:

Legality

China

As of October 2015 2-AI is a controlled substance in China.[7]

United States

2-Aminoindane is not scheduled at the federal level in the United States,[8] but may be considered an analog of amphetamine, in which case purchase, sale, or possession could be prosecuted under the Federal Analog Act.

See also

- 2-Aminodilin (2-AD)

- 2-Aminotetralin (2-AT)

- Amphetamine

- Bath salts (drug)

References

- Manier, Sascha K.; Felske, Christina; Eckstein, Niels; Meyer, Markus R. (October 2019). "The metabolic fate of two new psychoactive substances − 2-aminoindane and N-methyl-2-aminoindane − studied in vitro and in vivo to support drug testing". Drug Testing and Analysis. doi:10.1002/dta.2699. ISSN 1942-7611. PMID 31667988.

- Halberstadt, Adam L.; Brandt, Simon D.; Walther, Donna; Baumann, Michael H. (March 2019). "2-Aminoindan and its ring-substituted derivatives interact with plasma membrane monoamine transporters and α2-adrenergic receptors". 236 (3): 989–999. doi:10.1007/s00213-019-05207-1. ISSN 1432-2072. PMID 30904940. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Simmler, Linda D.; Rickli, Anna; Schramm, York; Hoener, Marius C.; Liechti, Matthias E. (15 March 2014). "Pharmacological profiles of aminoindanes, piperazines, and pipradrol derivatives". Biochemical Pharmacology. 88 (2): 237–244. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2014.01.024. ISSN 0006-2952. PMID 24486525.

- Pinterova, N; Horsley, RR; Palenicek, T (2017). "Synthetic Aminoindanes: A Summary of Existing Knowledge". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 8: 236. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00236. PMC 5698283. PMID 29204127.

- Oberlender R, Nichols DE. (1991). "Structural variation and (+)-amphetamine-like discriminative stimulus properties". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 38 (3): 581–586. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(91)90017-V. PMID 2068194.

- "Åtta ämnen föreslås klassas som narkotika eller hälsofarlig vara" (in Swedish). Folkhälsomyndigheten. 24 June 2019.

- "关于印发《非药用类麻醉药品和精神药品列管办法》的通知" (in Chinese). China Food and Drug Administration. 27 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- 21 CFR — SCHEDULES OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES §1308.11 Schedule I.