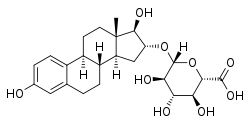

Estriol glucuronide

Estriol glucuronide (E3G), or oestriol glucuronide, also known as estriol monoglucuronide, as well as estriol 16α-β-D-glucosiduronic acid, is a natural, steroidal estrogen and the glucuronic acid (β-D-glucopyranuronic acid) conjugate of estriol.[1][2] It occurs in high concentrations in the urine of pregnant women as a reversibly formed metabolite of estriol.[2] Estriol glucuronide is a prodrug of estriol,[3] and was the major component of Progynon and Emmenin, estrogenic products manufactured from the urine of pregnant women that were introduced in the 1920s and 1930s and were the first orally active estrogens.[4][5] Emmenin was succeeded by Premarin (conjugated equine estrogens), which is sourced from the urine of pregnant mares and was introduced in 1941.[4][5][6] Premarin replaced Emmenin due to the fact that it was easier and less expensive to produce.[4][5]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Estriol glucuronidate; (16α,17β)-16,17-Dihydroxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-3-yl D-glucopyranosiduronic acid; β-D-Glucopyranuronic acid, monoglycoside with (16α,17β)-estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,16,17-triol |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.161.795 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H32O9 |

| Molar mass | 464.511 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Estrogen glucuronides can be deglucuronidated into the corresponding free estrogens by β-glucuronidase in tissues that express this enzyme, such as the mammary gland.[7] As a result, estrogen glucuronides have estrogenic activity via conversion into estrogens.[7]

The positional isomer of estriol 16α-glucuronide, estriol 3-glucuronide, also occurs as an endogenous metabolite of estriol, although to a much lower extent in comparison.[8][9][10]

See also

- Catechol estrogen

- Estradiol glucuronide

- Estradiol sulfate

- Estrogen conjugate

- Estrone glucuronide

- Estrone sulfate

- Lipoidal estradiol

References

- R.A. Hill; H.L.J. Makin; D.N. Kirk; G.M. Murphy (23 May 1991). Dictionary of Steroids. CRC Press. pp. 274–. ISBN 978-0-412-27060-4.

- HASHIMOTO Y, NEEMAN M (1963). "Isolation and characterization of estriol 16 alpha-glucosiduronic acid from human pregnancy urine". J. Biol. Chem. 238: 1273–82. PMID 14010351.

- Geoffrey Dutton (2 December 2012). Glucuronic Acid Free and Combined: Chemistry, Biochemistry, Pharmacology, and Medicine. Elsevier. pp. 466–. ISBN 978-0-323-14398-1.

- Thom Rooke (1 January 2012). The Quest for Cortisone. MSU Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-1-60917-326-5.

- Georgina D. Feldberg (2003). Women, Health and Nation: Canada and the United States Since 1945. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-0-7735-2501-6.

- Nick Panay; Paula Briggs; Gab Kovacs (20 August 2015). Managing the Menopause. Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-1-107-45182-7.

- Zhu BT, Conney AH (January 1998). "Functional role of estrogen metabolism in target cells: review and perspectives". Carcinogenesis. 19 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1093/carcin/19.1.1. PMID 9472688.

- http://www.hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB10335

- Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 265–. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1.

- Musey, Paul I.; Kirdani, Rashad Y.; Bhanalaph, Thongchai; Sandberg, Avery A. (1973). "Estriol metabolism in the baboon: Analysis of urinary and biliary metabolites". Steroids. 22 (6): 795–817. doi:10.1016/0039-128X(73)90054-8. ISSN 0039-128X.