Ranitidine

Ranitidine, sold under the trade name Zantac among others, is a medication which decreases stomach acid production.[2] It is commonly used in treatment of peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and Zollinger–Ellison syndrome.[2] There is also tentative evidence of benefit for hives.[4] It can be taken by mouth, by injection into a muscle, or into a vein.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /rəˈnɪtɪdiːn/ |

| Trade names | Zantac, others |

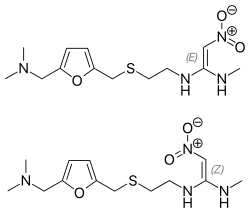

| Other names | Dimethyl [(5-{[(2-{[1-(methylamino)-2-nitroethenyl]amino}ethyl)sulfanyl]methyl}furan-2-yl)methyl]amine, ranitidine hydrochloride (JAN JP) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601106 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, IV |

| Drug class | H2 receptor blocker |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50% (by mouth)[2] |

| Protein binding | 15% |

| Metabolism | Liver: FMOs, including FMO3; other enzymes |

| Onset of action | 55–65 minutes (150 mg dose)[3] 55–115 minutes (75 mg dose)[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 2–3 hours |

| Excretion | 30–70% Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.060.283 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

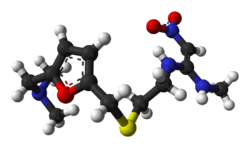

| Formula | C13H22N4O3S |

| Molar mass | 314.40 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Common side effects include headaches and pain or burning if given by injection.[2] Serious side effects may include liver problems, a slow heart rate, pneumonia, and the potential of masking stomach cancer.[2] It is also linked to an increased risk of Clostridium difficile colitis.[5] It is generally safe in pregnancy.[2] Ranitidine is an H2 histamine receptor antagonist that works by blocking histamine and thus decreasing the amount of acid released by cells of the stomach.[2]

Ranitidine was discovered in 1976, and came into commercial use in 1981.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[2] The 2015 wholesale price in the developing world was about US$0.01–0.05 per pill.[8] In the United States it is about $0.05 per dose.[2] In 2016, it was the 50th most prescribed medication in the United States with more than 15 million prescriptions.[9] In September 2019, the toxin N-nitrosodimethylamine was discovered to occur in ranitidine from a number of manufacturers, resulting in distribution stops and recalls.[10][11][12][13]

Medical uses

- Relief of heartburn

- Short-term and maintenance therapy of gastric and duodenal ulcers

- Ranitidine can also be given with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to reduce the risk of ulceration. Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) are more effective for the prevention of NSAID-induced ulcers.[14]

- Pathologic gastrointestinal (GI) hypersecretory conditions such as Zollinger–Ellison syndrome

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Erosive esophagitis

- Part of a multidrug regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication to reduce the risk of duodenal ulcer recurrence

- Recurrent postoperative ulcer

- Upper GI bleeding

- Prevention of acid-aspiration pneumonitis during surgery: ranitidine can be administered preoperatively to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia. The drug increases gastric pH, but generally has no effect on gastric volume. In a 2009 meta-analysis comparing the net benefit of proton pump inhibitors and ranitidine to reduce the risk of aspiration before anesthesia, ranitidine was found to be more effective than proton pump inhibitors in reducing the volume of gastric secretions.[15] Ranitidine may have an antiemetic effect when administered preoperatively.

- Prevention of stress-induced ulcers in critically ill patients[16]

- Used together with diphenhydramine as secondary treatment for anaphylaxis; after first-line epinephrine.[17][18]

Preparations

Certain preparations of ranitidine are available over the counter (OTC) in various countries. In the United States, 75- and 150-mg tablets are available OTC. Since 2017, Zantac is marketed in the U.S. by Sanofi.[19][20] In Australia and the UK, packs containing seven or 14 doses of the 150-mg tablet are available in supermarkets, small packs of 150-mg and 300-mg tablets are schedule 2 pharmacy medicines. Larger doses and pack sizes require a prescription.

Dosing

For ulcer treatment, a night-time dose is especially important — as the increase in gastric/duodenal pH promotes healing overnight when the stomach and duodenum are empty. Conversely, for treating reflux, smaller and more frequent doses are more effective.

Ranitidine used to be administered long-term for reflux treatment, sometimes indefinitely. However, proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) have taken over this role. In addition, a fairly rapid tachyphylaxis can develop within six weeks of initiation of treatment, further limiting its potential for long-term use.[21]

People with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome have been given very high doses without any harm.[22]

Contraindication

Ranitidine is contraindicated for patients known to have hypersensitivity to the drug.

Adverse effects

The following adverse effects have been reported as events in clinical trials:

Central nervous system

Rare reports have been made of malaise, dizziness, somnolence, insomnia, and vertigo. In severely ill, elderly patients, cases of reversible mental confusion, agitation, depression, and hallucinations have been reported.[23] Ranitidine causes fewer CNS adverse reactions and drug interactions compared with cimetidine.

Cardiovascular

Arrhythmias such as tachycardia, bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and premature ventricular beats have also been reported.[23]

Gastrointestinal

All drugs in its class have the potential to cause vitamin B12 deficiency secondary to a reduction in food-bound vitamin B12 absorption.[24] Elderly patients taking H2 receptor antagonists are more likely to require B12 supplementation than those not taking such drugs.[25] H2 blockers may also reduce the absorption of drugs (azole antifungals, calcium carbonate) that require an acidic stomach.[26] In addition, multiple studies suggest the use of H2 receptor antagonists such as raniditine may increase the risk of infectious diarrhoea, including traveller's diarrhoea and salmonellosis.[27][28][29][30][31] A 2005 study found that by suppressing acid-mediated breakdown of proteins, ranitidine may lead to an elevated risk of developing food or drug allergies, due to undigested proteins then passing into the gastrointestinal tract, where sensitisation occurs. Patients who take these agents develop higher levels of immunoglobulin E against food, whether they had prior antibodies or not.[32] Even months after discontinuation, an elevated level of IgE in six percent of patients was still found in the study.

Liver

Cholestatic hepatitis, liver failure, hepatitis, and jaundice have been noted, and require immediate discontinuation of the drug.[23] Blood tests can reveal an increase in liver enzymes or eosinophilia, although in rare instances, severe cases of hepatotoxicity may require a liver biopsy.[33]

Lungs

Ranitidine and other histamine H2 receptor antagonists may increase the risk of pneumonia in hospitalized patients.[34] They may also increase the risk of community-acquired pneumonia in adults and children.[35]

Blood

Thrombocytopenia is a rare but known side effect. Drug-induced thrombocytopenia usually takes weeks or months to appear, but may appear within 12 hours of drug intake in a sensitized individual. Typically, the platelet count falls to 80% of normal, and thrombocytopenia may be associated with neutropenia and anemia.[36]

Skin

Rash, including rare cases of erythema multiforme, and rare cases of hair loss and vasculitis have been seen.[23]

Precautions

Disease-related concerns

Relief of symptoms due to the use of ranitidine does not exclude the presence of a gastric malignancy. In addition, with kidney or liver impairment, ranitidine must be used with caution. Ranitidine should be avoided in patients with porphyria, as it may precipitate an attack.[37][38]

Pregnancy

This drug is rated pregnancy category B in the United States.[1]

Lactation

Ranitidine enters breast milk, with peak concentrations seen at 5.5 hours after the dose in breast milk. Caution should be exercised when prescribed to nursing women.[39]

Children

In children, the use of gastric acid inhibitors has been associated with an increased risk for development of acute gastroenteritis and community-acquired pneumonia.[40] A cohort analysis including over 11,000 neonates reported an association of H2 blocker use and an increased incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight (VLBW) neonates.[41] In addition, about a sixfold increase in mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, and infection (such as sepsis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection) was reported in patients receiving ranitidine in a cohort analysis of 274 VLBW neonates.[42]

Drug tests

Ranitidine may return a false positive result with some commercial kits for testing for drugs of abuse.[43]

Cancer-causing impurities

In September 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) learned that some ranitidine medicines, including some products sold under the brand name Zantac, contained a nitrosamine impurity called N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), classified as a probable human carcinogen, at low levels.[11][44] Health Canada announced that it was assessing NDMA in ranitidine[10] and requested that manufacturers stop the distribution of ranitidine products in Canada until the NDMA levels in the products are found to be safe.[45] Health Canada announced that ranitidine drugs were being recalled by Sandoz Canada, Apotex Inc., Pro Doc Limitée, Sanis Health Inc., and Sivem Pharmaceuticals ULC.[45] The European Medicines Agency (EMA) started an EU-wide review of ranitidine medicines at the request of the European Commission.[12][46]

In September 2019, Sandoz issued a "precautionary distribution stop" of all medicines containing ranitidine.[47][48] followed a few days later by a recall of ranitidine hydrochloride capsules in the United States.[49][50][51] The Italian Medicines Agency, AIFA, recalled all ranitidine that uses an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) from Saraca Laboratories.[52][53][54] The German Pharmacists Committee (AMK) published a list of recalled products.[55] The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in Australia published a list of recalled products.[56]

In September 2019, Apotex recalled all over-the-counter (OTC) ranitidine tablets sold in the United States at Walmart, Rite Aid, and Walgreens.[57][58] Subsequently, Walmart, Rite Aid, Walgreens, and CVS pulled Zantac and some generics from their shelves.[59][60][61][62][63]

In October 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) observed that a third-party laboratory was using higher temperatures in its tests to look for nitrosamine impurities. The NDMA was generated by the added heat but the higher temperatures were recommended for using a gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS) method to test for NDMA in valsartan and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs).[64] The FDA stated that it recommends using a liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) testing protocol to test samples of ranitidine.[65] Its LC-HRMS testing method does not use elevated temperatures and has shown the presence of much lower levels of NDMA in ranitidine medicines than reported by the third-party laboratory. International regulators using similar LC-MS testing methods have also shown the presence of low levels of NDMA in ranitidine samples.[13] The FDA provided additional guidance about using another liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) method based on a triple-quadrupole MS platform.[13][66]

In October 2019, Sanofi recalled all over-the-counter Zantac in the United States and Canada,[67][68][13] Perrigo issued a worldwide recall of ranitidine,[69][13], Dr. Reddy's issued a recall of all ranitidine products in the United States,[70][13] and Novitium Pharma recalled all ranitidine hydrochloride capsules in the United States.[71][13]

In November 2019, the FDA stated that their tests have found levels of NDMA in ranitidine and nizatidine that are similar to the levels you would expect to be exposed to if you ate common foods like grilled or smoked meats.[72][73] They also stated that their simulated gastric fluid (SGF) model tests and their simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) model tests indicate that NDMA is not formed when exposed to acid in the stomach with a normal diet.[72][73] The FDA advised companies to recall their ranitidine if testing shows levels of NDMA above the acceptable daily intake (96 nanograms per day or 0.32 parts per million for ranitidine).[13] At the same time, they indicated that some levels of NDMA found in medicines still exceed what the FDA considers acceptable for these medicines.[72][73]

In November 2019, Aurobindo Pharma, Amneal Pharmaceuticals, American Health Packaging, Golden State Medical Supply, and Precision Dose recalled some lots of ranitidine tablets, capsules, and syrup.[74][75][76][77][78]

In December 2019, the FDA asked manufacturers of ranitidine and nizatidine products to expand their testing for NDMA to include all lots of the medication before making them available to consumers.[79]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Ranitidine is a competitive, reversible inhibitor of the action of histamine at the histamine H2 receptors found in gastric parietal cells. This results in decreased gastric acid secretion and gastric volume, and reduced hydrogen ion concentration.

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption: Oral: 50%

Protein binding: 15%

Metabolism: N-oxide is the principal metabolite.

Half-life elimination: With normal renal function, ranitidine taken orally has a half-life of 2.5–3.0 hours. If taken intravenously, the half-life is generally 2.0–2.5 hours in a patient with normal creatinine clearance.

Excretion: The primary route of excretion is the urine. In addition, about 30% of the orally administered dose is collected in the urine as non-absorbed drug in 24 hours.

Elderly

In the elderly population, the plasma half-life of ranitidine is prolonged to 3–4 hours secondary to decreased kidney function causing decreased clearance.[23]

Children

In general, studies of pediatric patients (aged one month to 16 years) have shown no significant differences in pharmacokinetic parameter values in comparison to healthy adults, when correction is made for body weight.[23]

History

Ranitidine was first prepared as AH19065 by John Bradshaw in the summer of 1977 in the Ware research laboratories of Allen & Hanburys, part of the Glaxo organization.[80][81] Its development was a response to the first in class histamine H2 receptor antagonist, cimetidine, developed by Sir James Black at Smith, Kline and French, and launched in the United Kingdom as Tagamet in November 1976. Both companies would eventually become merged as GlaxoSmithKline following a sequence of mergers and acquisitions starting with the integration of Allen & Hanbury's Ltd and Glaxo to form Glaxo Group Research in 1979, and ultimately with the merger of Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham in 2000. Ranitidine was the result of a rational drug-design process using what was by then a fairly refined model of the histamine H2 receptor and quantitative structure-activity relationships.

Glaxo refined the model further by replacing the imidazole ring of cimetidine with a furan ring with a nitrogen-containing substituent, and in doing so developed ranitidine. Ranitidine was found to have a far-improved tolerability profile (i.e. fewer adverse drug reactions), longer-lasting action, and 10 times the activity of cimetidine. Ranitidine has 10% of the affinity that cimetidine has to CYP450, so it causes fewer side effects, but other H2 blockers famotidine and nizatidine have no CYP450 significant interactions.[82]

Ranitidine was introduced in 1981, and was the world's biggest-selling prescription drug by 1987. It was largely superseded by the even more effective proton-pump inhibitors, with omeprazole becoming the biggest-selling drug for many years. When omeprazole and ranitidine were compared in a study of 144 people with severe inflammation and erosions or ulcers of the esophagus, 85% of those treated with omeprazole healed within eight weeks, compared with 50% of those given ranitidine. In addition, the omeprazole group reported earlier relief of heartburn symptoms.[83][84]

References

- Use During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

- "Ranitidine Hydrochloride Monograph". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Gardner JD, Ciociola AA, Robinson M, et al. (July 2002). "Determination of the time of onset of action of ranitidine and famotidine on intra-gastric acidity". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 16 (7): 1317–1326. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01291.x. PMID 12144582.

- Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ, Hu N (14 March 2012). "Histamine H2-receptor antagonists for urticaria". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008596.pub2. PMID 22419335. CD008596.

- Tleyjeh IM, Abdulhak AB, Abdulhak AA, et al. (2013). "The association between histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis". PLoS ONE. 8 (3): e56498. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...856498T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056498. PMC 3587620. PMID 23469173.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 444. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- "World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019". 2019. hdl:10665/325771. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Ranitidine". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- "The Top 300 of 2019". clincalc.com. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- "Health Canada assessing NDMA in ranitidine". Health Canada. 13 September 2019. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- "Statement alerting patients and health care professionals of NDMA found in samples of ranitidine". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 13 September 2019. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- "EMA to provide guidance on avoiding nitrosamines in human medicines". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 13 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "FDA Updates and Press Announcements on NDMA in Zantac (ranitidine)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 October 2019. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

FDA observed the testing method used by a third-party laboratory uses higher temperatures. The higher temperatures generated very high levels of NDMA from ranitidine products because of the test procedure. FDA published the method for testing angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) for nitrosamine impurities. That method is not suitable for testing ranitidine because heating the sample generates NDMA.

FDA recommends using an LC-HRMS testing protocol to test samples of ranitidine. FDA's LC-HRMS testing method does not use elevated temperatures and has shown the presence of much lower levels of NDMA in ranitidine medicines than reported by the third-party laboratory. International regulators using similar LC-MS testing methods have also shown the presence of low levels of NDMA in ranitidine samples.

- "Reflux Remedies: ranitidine". PharmaSight OTC Health. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- Clark K, Lam LT, Gibson S, et al. (2009). "The effect of ranitidine versus proton pump inhibitors on gastric secretions: a meta-analysis of randomised control trials". Anaesthesia. 64 (6): 652–657. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05861.x. PMID 19453319.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. (2013). "Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012". Intensive Care Med. 39 (2): 165–228. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8. PMC 2249616. PMID 23361625.

- Tang AW (October 2003). "A practical guide to anaphylaxis". Am Fam Physician. 68 (7): 1325–32. PMID 14567487. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- "Anaphylaxis: Diagnosis and Management in the Rural Emergency Department" (PDF). American Journal of Clinical Medicine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- "Zantac". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). NDA 021698. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "CVS suspends Zantac sales, as recalls widen over carcinogen fears". BioPharma Dive. 30 September 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Lightdale JR, Gremse DA, Section on Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (2013). "Gastroesophageal reflux: management guidance for the pediatrician". Pediatrics. 131 (5): e1684–e1695. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0421. PMID 23629618.

- "Ranitidine Drug Information". Lexicomp. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- "Zantac Drug Insert" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Force RW, Nahata MC (1992). "Effect of histamine H2-receptor antagonists on vitamin B12 absorption". Ann Pharmacother. 26 (10): 1283–1286. doi:10.1177/106002809202601018. PMID 1358279.

- Mitchell SL, Rockwood K (2001). "The association between antiulcer medication and initiation of cobalamin replacement in older persons". J Clin Epidemiol. 54 (5): 531–534. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00340-1. PMID 11337218.

- "Reflux Remedies: ranitidine". PharmaSight OTC Health. PharmaSight.org. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- Cobelens FG, Leentvarr-Kuijpers A, Kleijnen J, et al. (November 1998). "Incidence and risk factors of diarrhoea in Dutch travellers: Consequences for priorities in pre-travel health advice". Trop Med Intern Health. 3 (11): 896–903. PMID 9855403.

- Neal KR, Briji SO, Slack RC, et al. (1994). "Recent treatment with H2 antagonists and antibiotics and gastric surgery as risk factors for Salmonella infection". BMJ. 308 (6922): 176. doi:10.1136/bmj.308.6922.176. PMC 2542523. PMID 7906170.

- Neal KR, Scott HM, Slack RC, et al. (1996). "Omeprazole as a risk factor for campylobacter gastroenteritis: case-control study". BMJ. 312 (7028): 414–415. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7028.414. PMC 2350063. PMID 8601113.

- Wickramasinghe LS, Basu SK (1984). "Salmonellosis during treatment with ranitidine". Unreviewed reports. BMJ. 289 (6454): 1272. doi:10.1136/bmj.289.6454.1272.

- Ruddell WS, Axon AT, Findlay JM, et al. (1980). "Effect of cimetidine on gastric bacterial flora". Lancet. i (8170): 672–674. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92826-3. PMID 6103090.

- Untersmayr E, Bakos N, Schöll I, et al. (2005). "Anti-ulcer drugs promote IgE formation toward dietary antigens in adult patients". FASEB J. 19 (6): 656–658. doi:10.1096/fj.04-3170fje. PMID 15671152.

- "Ranitidine: Hepatotoxicity". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 28 June 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Mallow S, Rebuck JA, Osler T, et al. (2004). "Do proton pump inhibitors increase the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia and related infectious complications when compared with histamine-2 receptor antagonists in critically ill trauma patients?". Curr Surg. 61 (5): 452–458. doi:10.1016/j.cursur.2004.03.014. PMID 15475094.

- Canani RB, Cirillo P, Roggero P, et al. (May 2006). "Therapy with gastric acidity inhibitors increases the risk of acute gastroenteritis and community-acquired pneumonia in children". Pediatrics. 117 (5): e817–20. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1655. PMID 16651285.

- Bangia AV, Kamath N, Mohan V (2011). "Ranitidine-induced thrombocytopenia: A rare drug reaction". Indian J Pharmacol. 43 (1): 76–7. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.75676. PMC 3062128. PMID 21455428.

- "Ranitidine Drug Information". Lexicomp. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014.

- "Ranitidine - core safety profile" (PDF). Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und MedizinProdukte.

- "Ranitidine". Lexicomp. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Canani RB, Cirillo P, Roggero P, et al. (2006). "Therapy with gastric acidity inhibitors increases the risk of acute gastroenteritis and community-acquired pneumonia in children". Pediatrics. 117 (5): e817–20. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1655. PMID 16651285.

- Guillet R, Stoll BJ, Cotten CM, et al. (2006). "Association of H2-blocker therapy and higher incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants". Pediatrics. 117 (2): e137–42. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1543. PMID 16390920.

- Terrin G, Passariello A, De Curtis M, et al. (2012). "Ranitidine is associated with infections, necrotizing enterocolitis, and fatal outcome in newborns". Pediatrics. 129 (1): 40–5. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0796. PMID 22157140.

- Brahm NC, Yeager LL, Fox MD, et al. (15 August 2010). "Commonly prescribed medications and potential false-positive urine drug screens". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 67 (16): 1344–50. doi:10.2146/ajhp090477. PMID 20689123.

- "Questions and Answers: NDMA impurities in ranitidine (commonly known as Zantac)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 11 October 2019. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Health Canada requests that companies stop distributing ranitidine drugs in Canada while it assesses NDMA; additional products being recalled - Recalls and safety alerts". Health Canada. 26 September 2019. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- "EMA to review ranitidine medicines following detection of NDMA". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 13 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- Bomey N (19 September 2019). "Ranitidine warnings: Generic Zantac distribution halted on cancer fear". USA Today. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Palmer E (19 September 2019). "Novartis doesn't wait for FDA investigation and halts distribution of its generic Zantac". FiercePharma. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

Novartis on Wednesday said it was stopping worldwide distribution of its generic versions of the antacid while regulators investigate the fact that the impurity N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) has been detected these ranitidine-based drugs.

- "Sandoz ceases distribution of ranitidine product". Pharmaceutical news, Pharma industry, Pharmaceutical manufacturing. 19 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Sandoz expands recall of antacid". Pharmaceutical news, Pharma industry, Pharmaceutical manufacturing. 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Sandoz Inc. Issues Voluntary Recall of Ranitidine Hydrochloride Capsules 150mg and 300mg Due to an Elevated Amount of Unexpected Impurity, N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), in the Product" (Press release). Sandoz Inc. 23 September 2019. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019 – via PR Newswire.

- Thomas K (19 September 2019). "Should You Keep Taking Zantac for Your Heartburn?". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Carcinogen scare sets off global race to contain tainted Zantac". Los Angeles Times. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "notizia". Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (in Italian). Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Online Nachricht: AMK: Liste der (Chargen-)Rückrufe Ranitidin-haltiger Arzneimittel". ABDA (in German). 17 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Ranitidine". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 17 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- "Apotex Corp. Issues Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Ranitidine Tablets 75mg and 150mg (All pack sizes and Formats) due to the potential for Detection of an Amount of Unexpected Impurity,N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Impurity in the product". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 26 September 2019. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- "Heartburn drug recalled, removed from shelves over cancer concerns". United Press International. 30 September 2019.

- Garcia SE (30 September 2019). "Zantac Pulled From Shelves by Walgreens, Rite Aid and CVS Over Carcinogen Fears". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "CVS Pharmacy Statement Regarding Zantac and Other Ranitidine Products". CVS Health. 3 October 2019. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Kazin M (2 October 2019). "Walmart suspends sale of Zantac, other products containing ranitidine over cancer risk". Fox Business. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Criss D (30 September 2019). "Walmart, CVS, Walgreens pull Zantac and similar heartburn drugs because of cancer worries". CNN. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- Edney A (30 September 2019). "Major U.S. Drugstore Chains Pull Zantac Amid Carcinogen Concern". Bloomberg. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "FDA Updates and Press Announcements on Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker (ARB) Recalls (Valsartan, Losartan, and Irbesartan)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 September 2019. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) Method for the Determination of NDMA in Ranitidine Drug Substance and Drug Product (PDF) (Report). FY19-177-DP A-S. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019.

- Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) Method for the Determination of NDMA in Ranitidine Drug Substance and Solid Dosage Drug Product (PDF) (Report). 17 October 2019. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019.

- Thomas K (18 October 2019). "Zantac Recall Widens as Sanofi Pulls Its Drug Over Carcinogen Fears". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- "Sanofi Provides Update on Precautionary Voluntary Recall of Zantac OTC in U.S." U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 October 2019. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Perrigo Company plc Issues Voluntary Worldwide Recall of Ranitidine Due to Possible Presence of Impurity, N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Impurity in the Product". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 October 2019. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Dr. Reddy's Confirms its Voluntary Nationwide Recall of All Ranitidine Products in the U.S. Market". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 October 2019. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Novitium Pharma Issues Voluntary National Recall of Ranitidine Hydrochloride Capsules 150mg and 300mg Due to an Elevated Amount of Unexpected Impurity, N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 25 October 2019. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Statement on new testing results, including low levels of impurities in ranitidine drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 1 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Laboratory Tests - Ranitidine". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Aurobindo Pharma USA, Inc. Initiates Voluntary Nationwide Consumer Level Recall of 38 Lots of Ranitidine Tablets 150mg, Ranitidine Capsules 150mg, Ranitidine Capsules 300mg and Ranitidine Syrup 15mg/mL Due to the Detection of NDMA (Nitrosodimethylamine) Impurity". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 6 November 2019. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- "Amneal Pharmaceuticals, LLC. Issues Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Ranitidine Tablets, USP, 150mg and 300mg, and Ranitidine Syrup (Ranitidine Oral Solution, USP), 15 mg/mL, Due to Possible Presence of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Impurity". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 12 November 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "American Health Packaging Issues Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Ranitidine Syrup (Ranitidine Oral Solution USP) 150 mg/10 mL Liquid Unit Dose Cups Due to the Detection of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Impurity". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 8 November 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Golden State Medical Supply, Inc. Issues a Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Ranitidine Hydrochloride 150mg and 300mg Capsules (Manufactured by Novitium Pharma LLC) Due to an Elevated Amount of Unexpected Impurity, N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 November 2019. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- "Precision Dose Inc. Issues Voluntary Nationwide Recall of Ranitidine Oral Solution, USP 150 mg/10 mL Due to Possible Presence of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Impurity". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- "FDA Updates and Press Announcements on NDMA in Zantac (ranitidine)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 4 December 2019. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

Today, we are announcing that we have asked manufacturers of ranitidine and nizatidine products to expand their testing for NDMA to include all lots of the medication before making them available to consumers. If testing shows NDMA above the acceptable daily intake limit (96 nanograms per day or 0.32 parts per million for ranitidine), the manufacturer must inform the agency and should not release the lot for consumer use.

- Lednicer D, ed. (1993). Chronicles of Drug Discovery. ACS Professional Reference Book. 3. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 45–81. ISBN 978-0-8412-2733-0.

- US patent 4128658, "Aminoalkyl furan derivatives"

- Laurence Brunton, John Lazo, Keith Parker (August 2005). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11 ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 972. doi:10.1036/0071422803. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016.

- Pelot, Daniel, (M.D.). "Digestive System : New Drug for Heartburn". The New Book of Knowledge : Medicine & Health, Grolier : Danbury, Connecticut. 1990. p.262. ISBN 0-7172-8244-9. Library of Congress 82-645223

- Yeomans ND, Tulassay Z, Juhász L, et al. (March 1998). "A comparison of omeprazole with ranitidine for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Acid Suppression Trial: Ranitidine versus Omeprazole for NSAID-associated Ulcer Treatment (ASTRONAUT) Study Group". N. Engl. J. Med. 338 (11): 719–26. doi:10.1056/NEJM199803123381104. PMID 9494148.