Vulva

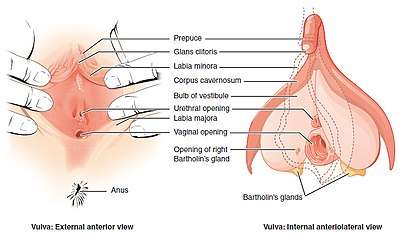

The vulva (plural vulvas or vulvae; derived from Latin for wrapper or covering) consists of the external female sex organs. The vulva includes the mons pubis (or mons veneris), labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibular bulbs, vulval vestibule, urinary meatus, the vaginal opening, and Bartholin's and Skene's vestibular glands. The urinary meatus is also included as it opens into the vulval vestibule. Other features of the vulva include the pudendal cleft, sebaceous glands, the urogenital triangle (anterior part of the perineum), and pubic hair. The vulva includes the entrance to the vagina, which leads to the uterus, and provides a double layer of protection for this by the folds of the outer and inner labia. Pelvic floor muscles support the structures of the vulva. Other muscles of the urogenital triangle also give support.

| Human vulva | |

|---|---|

Vulvas of different women (pubic hair removed in some cases) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Genital tubercle, urogenital folds |

| Artery | Internal pudendal artery |

| Vein | Internal pudendal veins |

| Nerve | Pudendal nerve |

| Lymph | Superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pudendum muliebre |

| MeSH | D014844 |

| TA | A09.2.01.001 |

| FMA | 20462 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Blood supply to the vulva comes from the three pudendal arteries. The internal pudendal veins give drainage. Afferent lymph vessels carry lymph away from the vulva to the inguinal lymph nodes. The nerves that supply the vulva are the pudendal nerve, perineal nerve, ilioinguinal nerve and their branches. Blood and nerve supply to the vulva contribute to the stages of sexual arousal that are helpful in the reproduction process.

Following the development of the vulva, changes take place at birth, childhood, puberty, menopause and post-menopause. There is a great deal of variation in the appearance of the vulva particularly in relation to the labia minora. The vulva can be affected by many disorders which may often result in irritation. Vulvovaginal health measures can prevent many of these. Other disorders include a number of infections and cancers. There are several vulval restorative surgeries known as genitoplasties, and some of these are also used as cosmetic surgery procedures.

Different cultures have held different views of the vulva. Some ancient religions and societies have worshipped the vulva and revered the female as a goddess. Major traditions in Hinduism continue this. In western societies there has been a largely negative attitude typified by the medical terminology of pudenda membra, meaning parts to be ashamed of. There has been an artistic reaction to this in various attempts to bring about a more positive and natural outlook, such as work from British, American, and Japanese artists. While the vagina is a separate part of the anatomy, it has often been used synonymously with vulva.

Structure

The main structures of the vulva are: the mons pubis, the labia majora and labia minora, the external parts of the clitoris – the clitoral hood and the glans, the urinary meatus, the vaginal opening and hymen, and Bartholin's and Skene's vestibular glands.[1] Other features include the pudendal cleft, pubic hair, sebaceous glands, the vulval vestibule, and the urogenital triangle.[2]

Mons pubis

The mons pubis is the soft mound of fatty tissue at the front of the vulva, in the pubic region covering the pubic bone.[3] Mons pubis is Latin for "pubic mound" and is present in both sexes to act as a cushion during sexual intercourse, and is more pronounced in the female.[4] The variant term mons veneris ('mound of Venus') is used specifically for females.[5][4] The lower part of the mons pubis is divided by a fissure – the pudendal cleft – which separates the mons pubis into the labia majora. After puberty, the clitoral hood and the labia minora can protrude into the pudendal cleft in a variable degree.[6] The mons and labia majora become covered in pubic hair at puberty.[7]

Labia

The labia majora and the labia minora cover the vulval vestibule.[8] The outer pair of folds, divided by the pudendal cleft, are the labia majora (New Latin for "larger lips"). They contain and protect the other structures of the vulva.[8] The labia majora meet at the front at the mons pubis, and meet posteriorly at the urogenital triangle (the anterior part of the perineum) between the pudendal cleft and the anus.[9][6] The labia minora are often pink or brownish black, relevant to the person's skin color.[10]

The grooves between the labia majora and labia minora are called the interlabial sulci, or interlabial folds.[11] The labia minora (smaller lips) are the inner two soft folds, within the labia majora. They have more color than the labia majora[3] and contain numerous sebaceous glands.[12] They meet posteriorly at the frenulum of the labia minora, a fold of restrictive tissue. The labia minora meet again at the front of the vulva to form the clitoral hood, also known as the prepuce.[13]

The visible portion of the clitoris is the clitoral glans. Typically, this is roughly the size and shape of a pea, and can vary in size from about 6 mm to 25 mm.[13] The size can also vary when it is erect.[6] The clitoral glans contains as many nerve endings as the much larger homologous glans penis in the male, which makes it highly sensitive.[13] The only known function of the clitoris is to focus sexual feelings.[13] The clitoral hood is a protective fold of skin which varies in shape and size, and it may partially or completely cover the clitoris.[14] The clitoris is the homologue of the penis,[8] and the clitoral hood is the female equivalent of the male foreskin,[14] and may be partially or completely hidden within the pudendal cleft.[15]

Variations

There is a great deal of variation in the appearance of female genitals.[13] Much of this variation lies in the significant differences in the size, shape, and colour of the labia minora. Though called the smaller lips they can often be of considerable size and may protrude outside the vagina or labia majora.[13][6] This variation has also been evidenced in a large display of 400 vulval casts called the Great Wall of Vagina created by Jamie McCartney to fill the lack of information of what a normal vulva looks like. The casts taken from a large and varied group of women showed clearly that there is much variation.[16] Pubic hair also varies in its colour, texture, and amount of curl.[13]

Vestibule

The area between the labia minora where the vaginal opening and the urinary meatus are located is called the vulval vestibule, or vestibule of the vagina. The urinary meatus is below the clitoris and just in front of the vaginal opening which is near to the perineum. The term introitus is more technically correct than "opening", since the vagina is usually collapsed, with the opening closed. The introitus is sometimes partly covered by a membrane called the hymen. The hymen will usually rupture during the first episode of vigorous sex, and the blood produced by this rupture has been seen to signify virginity. However, the hymen may also rupture spontaneously during exercise or be stretched by normal activities such as the use of tampons and menstrual cups, or be so minor as to be unnoticeable, or be absent.[13] In some rare cases, the hymen may completely cover the vaginal opening, requiring a surgical procedure called a hymenotomy.[17] On either side of the back part of the vaginal opening are the two greater vestibular glands known as Bartholin's glands. These glands secrete mucus and a vaginal and vulval lubricant.[18] They are homologous to the bulbourethral glands in the male.[2] The lesser vestibular glands known as Skene's glands, are found on the anterior wall of the vagina. They are homologues of the male prostate gland and are also referred to as the female prostate.[19]

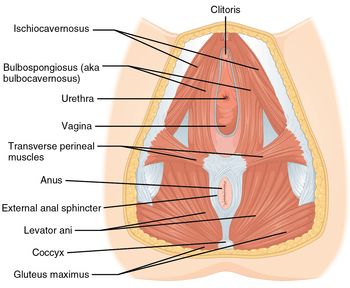

Muscles

Pelvic floor muscles help to support the vulvar structures. The voluntary, pubococcygeus muscle, part of the levator ani muscle partially constricts the vaginal opening.[20] Other muscles of the urogenital triangle support the vulvar area and they include the transverse perineal muscles, the bulbospongiosus, and the ischiocavernosus muscles.[21] The bulbospongiosus muscle decreases the vaginal opening.[9] Their contractions play a role in the vaginal contractions of orgasm by causing the vestibular bulbs to contract.[22]

Blood, lymph and nerve supply

The tissues of the vulva are highly vascularised and blood supply is provided by the three pudendal arteries.[23] Venous return is via the external and internal pudendal veins.[24] The organs and tissues of the vulva are drained by a chain of superficial inguinal lymph nodes located along the blood vessels.[25]

The ilioinguinal nerve originates from the first lumbar nerve and gives branches that include the anterior labial nerves which supply the skin of the mons pubis and the labia majora.[26] The perineal nerve is one of the terminal branches of the pudendal nerve and this branches into the posterior labial nerves to supply the labia.[26] The pudendal nerve branches include the dorsal nerve of clitoris which gives sensation to the clitoris.[26] The clitoral glans is seen to be populated by a large number of small nerves, a number that decreases as the tissue changes towards the urether.[27] The density of nerves at the glans indicates that it is the center of heightened sensation.[27] Cavernous nerves from the uterovaginal plexus supply the erectile tissue of the clitoris.[28] These are joined underneath the pubic arch by the dorsal nerve of the clitoris.[29] The pudendal nerve enters the pelvis through the lesser sciatic foramen and continues medial to the internal pudendal artery. The point where the nerve circles the ischial spine is the location where a pudendal block of local anesthetic can be administered to inhibit sensation to the vulva.[30] A number of smaller nerves split off from the pudendal nerve. The deep branch of the perineal nerve supplies the muscles of the perineum and a branch of this supplies the bulb of the vestibule.[31][32]

Development

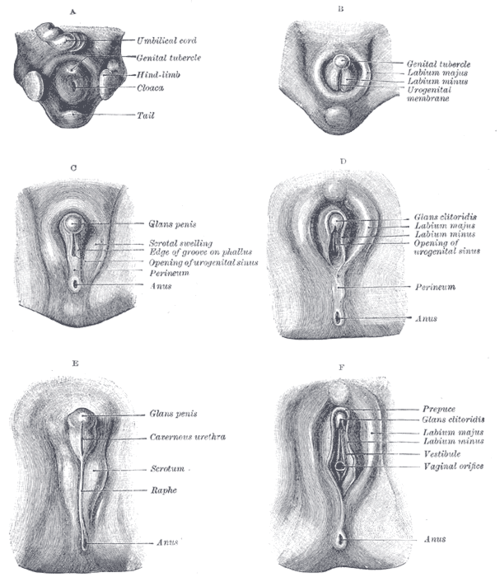

Prenatal development

In week three of the development of the embryo, mesenchyme cells from the primitive streak migrate around the cloacal membrane.[33] Early in the fifth week the cells form two swellings called the cloacal folds.[34] The cloacal folds meet in front of the cloacal membrane and form a raised area known as the genital tubercle.[34][33] The urorectal septum fuses with the cloacal membrane to form the perineum. This division creates two areas one surrounded by the urethral folds and the other by the anal folds.[34][33] These areas become the urogenital triangle and the anal triangle.[2] The area between the vagina and the anus is known as the clinical perineum.[2]

At the same time a pair of swellings on either side of the urethral folds known as the genital swellings develop into the labioscrotal swellings.[34][33] Sexual differentiation takes place, and at the end of week 6 in the female, hormones stimulate further development and the genital tubercle bends and forms the clitoris.[34][33] The urethral folds form the labia minora and the labioscrotal swellings form the labia majora. At this time the sexes still cannot be distinguished.[33] The appearance of the external genitalia is similar in male and female embryos until the twelfth week and even then is difficult to distinguish.[34]

The uterovaginal canal or genital canal, forms in the third month of the development of the urogenital system. The lower part of the canal is blocked off by a plate of tissue, the vaginal plate. This tissue develops and lengthens during the third to fifth months and the lower part of the vaginal canal is formed by a process of desquamation or cell shedding. The end of the vaginal canal is blocked off by an endodermal membrane which separates the opening from the vestibule. In the fifth month the membrane degenerates but leaves a remnant called the hymen.[34]

Organs in the male and female with a shared common ancestry are said to be homologous.[2] The clitoral glans is homologous to the male glans penis,[22] and the clitoral body and the clitoral crura are homologous to the corpora cavernosa of the penis.[1] The labia majora is homologous to the scrotum;[2] the clitoral hood is homologous to the foreskin,[14] and the labia minora is homologous to the spongy urethra.[1] The vestibular bulbs beneath the skin of the labia minora are homologous to the corpus spongiosum, the tissue of the penis surrounding the urethra, and to the bulb of the penis.[1] Bartholin's glands are homologous to the bulbourethral glands in males.[2]

Childhood

The newborn's vulva may be swollen or enlarged as a result of having been exposed, via the placenta, to her mother's increased levels of hormones.[35] The labia majora are closed.[36] These changes disappear over the first few months.[35] During childhood before puberty, the lack of estrogen can cause the labia to become sticky and to ultimately join firmly together. This condition is known as labial fusion and is rarely found after puberty when oestrogen production has increased.[37]

Puberty

Puberty is the onset of the ability to reproduce, and takes place over two to three years, producing a number of changes.[38][7] The structures of the vulva become proportionately larger and may become more pronounced.[39] Pubarche, the first appearance of pubic hair develops, firstly on the labia majora, and later spreads to the mons pubis, and sometimes to the inner thighs and perineum. Pubic hair is much coarser than other body hair, and is considered a secondary sex characteristic.[40] Pubarche can occur independently of puberty. Premature pubarche may sometimes indicate a later metabolic-endocrine disorder seen at adolescence. The disorder sometimes known as a polyendocrine disorder is marked by elevated levels of androgen, insulin, and lipids, and may originate in the fetus. Instead of being seen as a normal variant it is proposed that premature pubarche may be seen as a marker for these later endocrine disorders.[41]

Apocrine sweat glands secrete sweat into the pubic hair follicles. This is broken down by bacteria on the skin and produces an odor,[42] which some consider to act as an attractant sex pheromone.[43] The labia minora may grow more prominent and undergo changes in color.[44] At puberty the first monthly period known as menarche marks the onset of menstruation.[45] In prepubertal girls the skin of the vulva is thin and delicate, and its neutral pH makes it prone to irritation.[46] The production of the female sex hormone estradiol (an estrogen) at puberty, causes the perineal skin to thicken by keratinising, and this reduces the risk of infection.[47] Estrogen also causes the laying down of fat in the development of the secondary sex characteristics. This contributes to the maturation of the vulva with increases in the size of the mons pubis, and the labia majora and the enlargement of the labia minora.[39]

Pregnancy

In pregnancy the vulva and vagina take on a bluish colouring due to venous congestion. This appears between the eighth and twelfth week and continues to darken as the pregnancy continues.[2] Estrogen is produced in large quantities during pregnancy and this causes the external genitals to become enlarged. The vaginal opening and the vagina are also enlarged.[48] After childbirth a vaginal discharge known as lochia is produced and continues for about ten days.[48]

Menopause

During menopause, hormone levels decrease, which causes changes in the vulva known as vulvovaginal atrophy.[49] The decreased estrogen affects the mons, the labia, and the vaginal opening and can cause pale, itchy, and sore skin.[49] Other visible changes are a thinning of the pubic hair, a loss of fat from the labia majora, a thinning of the labia minora, and a narrowing of the vaginal opening. This condition has been renamed by some bodies as the genitourinary syndrome of menopause as a more comprehensive term.[49]

Function and physiology

The vulva has a major role to play in the reproductive system. It provides entry to, and protection for the uterus, and the right conditions in terms of warmth and moisture that aids in its sexual and reproductive functions. The external organs of the vulva are richly innervated and provide pleasure when properly stimulated. The mons pubis provides cushioning against the pubic bone during intercourse.[13]

A number of different secretions are associated with the vulva, including urine (from the urethral opening), sweat (from the apocrine glands), menses (leaving from the vagina), sebum (from the sebaceous glands), alkaline fluid (from the Bartholin's glands), mucus (from the Skene's glands), vaginal lubrication from the vaginal wall and smegma.[2][13] Smegma is a white substance formed from a combination of dead cells, skin oils, moisture and naturally occurring bacteria, that forms in the genitalia.[50] In females this thickened secretion collects around the clitoris and labial folds. It can cause discomfort during sexual activity as it can cause the clitoral glans to stick to the hood, and is easily removed by bathing.[13] Aliphatic acids known as copulins are also secreted in the vagina.[43] These are believed to act as pheromones. Their fatty acid composition, and consequently their odor changes in relation to the stages of the menstrual cycle.[43]

Sexual arousal

The clitoris and the labia minora are both erogenous areas in the vulva. Local stimulation can involve the clitoris, vagina and other perineal regions. The clitoris is the most sensitive. Sexual stimulation of the clitoris (by a number of means) can result in widespread sexual arousal, and if maintained can result in an orgasm. Stimulation to orgasm is optimally achieved by a massaging sensation.[39]

Sexual arousal results in a number of physical changes in the vulva. During arousal vaginal lubrication increases. Vulva tissue is highly vascularised; arterioles dilate in response to sexual arousal and the smaller veins will compress after arousal,[31][51] so that the clitoris and labia minora increase in size. Increased vasocongestion in the vagina causes it to swell, decreasing the size of the vaginal opening by about 30%. The clitoris becomes increasingly erect, and the glans moves towards the pubic bone, becoming concealed by the hood. The labia minora increase considerably in thickness. The labia minora sometimes change considerably in color, going from pink to red in lighter skinned women who have not borne a child, or red to dark red in those that have. Immediately prior to an orgasm, the clitoris becomes exceptionally engorged, causing the glans to appear to retract into the clitoral hood. Rhythmic muscle contractions occur in the outer third of the vagina, as well as the uterus and anus. Contractions become less intense and more randomly spaced as the orgasm continues. The number of contractions that accompany an orgasm vary depending on its intensity. An orgasm may be accompanied by female ejaculation, causing liquid from either the Skene's gland or bladder to be expelled through the urethra. The pooled blood begins to dissipate, although at a much slower rate if an orgasm has not occurred. The vagina and vaginal opening return to their normal relaxed state, and the rest of the vulva returns to its normal size, position and color.[52][13]

Clinical significance

Irritation

Irritation and itching of the vulva is called pruritus vulvae. This can be a symptom of many disorders, some of which may be determined by a patch test. The most common cause of irritation is thrush, a fungal infection. Vulvovaginal health measures can help to prevent many disorders including thrush.[53] Infections of the vagina such as vaginosis and of the uterus may produce vaginal discharge which can be an irritant when it comes into contact with the vulvar tissue.[54][55] Inflammation as vaginitis, and vulvovaginitis can result from this causing irritation and pain.[56] Ingrown hairs resulting from pubic hair shaving can cause folliculitis where the hair follicle becomes infected; or give rise to an inflammatory response known as pseudofolliculitis pubis.[57] A less common cause of irritation is genital lichen planus another inflammatory disorder. A severe variant of this is vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome which can lead to narrowing of the vagina,[58] or vulva destruction.[59] Many types of infection and other diseases including some cancers may cause irritation.[60][61]

Sexually transmitted infections

Vulvar organs and tissues can become affected by different infectious agents such as bacteria and viruses, or infested by parasites such as lice and mites. Over thirty types of pathogen can be sexually transmitted, and many of these affect the genitals. Most STIs do not produce symptoms or symptoms may be mild and not be indicative of an STI.[62] The practice of safe sex can greatly reduce the risk of infection from many sexually transmitted pathogens.[63] The use of condoms (either male or female condoms) is one of the most effective methods of protection.[62]

Bacterial infections include: chancroid – characterised by genital ulcers known as chancres; granuloma inguinale showing as inflammatory granulomas often described as nodules; syphilis –the primary stage classically presents with a single chancre, a firm, painless, non-itchy ulcer, but there may be multiple sores;[64] and gonorrhea that very often presents no symptoms but can result in discharge.[65]

Viral infections include human papillomavirus infection (HPV) – this is the most common STI and has many types.[66] Genital HPV can cause genital warts. There have been links made between HPV and vulvar cancer, though HPV most often causes cervical cancer.[67] Genital herpes is mostly asymptomatic but can present with small blisters that break open into ulcers.[68] HIV/AIDS is mostly transmitted through sexual activity, and the vulva in some cases can be affected by sores.[69] A highly contagious viral infection is molluscum contagiosum which is transmissible on close contact and causes water warts.[70][71]

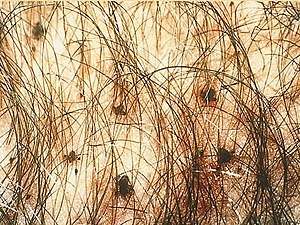

Parasitic infections include trichomoniasis, pediculosis pubis, and scabies. Trichomoniasis is transmitted by a parasitic protozoan and is the most common non-viral STI.[72] Most cases are asymptomatic but may present symptoms of irritation and a discharge of unusual odor.[73] Pediculosis pubis commonly called crabs, is a disease caused by the crab louse an ectoparasite.[61] When the pubic hair is infested the irritation produced can be intense.[61] Scabies, also known as the "seven year itch", is caused by another ectoparasite, the mite Sarcoptes scabiei, giving intense irritation.[61]

Cancer

Many malignancies can develop in vulvar structures.[31] Most vulvar cancers are squamous cell carcinomas and are usually found in the labia particularly the labia majora.[74] The second most common vulval cancer (though not very common) is vulval melanoma.[75] Signs and symptoms can include: itching, or bleeding; skin changes including rashes, sores, lumps or ulcers, and changes in vulval skin coloration. Pelvic pain might also occur especially during urinating and sex.[60] Vulval melanoma usually affects women over the age of fifty, and affects white women more than black women.[75] A vulvectomy may need to be performed in order to remove some or all of the vulva. This procedure is usually performed as a last resort in certain cases of cancer,[76] vulvar dysplasia or vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia.[77]

Other

Labial fusion, also called labial adhesion, is the fusion of the labia minora. This affects a number of young girls and is not considered unduly problematic. The condition can usually be treated using creams, or it may right itself with the release of hormones at the onset of puberty.[37][78]

Vulvodynia is chronic pain in the vulvar region. There is no single identifiable cause.[79] A subtype of this is vulvar vestibulitis but since this is not thought to be an inflammatory condition it is more usually referred to as vestibulodynia.[80] Vulvar vestibulitis usually affects pre-menopausal women.[80]

A number of skin disorders such as lichen sclerosus, and lichen simplex chronicus can affect the vulva. Crohn's disease of the vulva is an uncommon form of metastatic Crohn's disease which manifests as a skin condition showing as hypertrophic lesions or vulvar abscesses.[81] Papillary hidradenomas are nodules that can ulcerate and are mostly found on the skin of the labia or of the interlabial folds. Another more complex ulcerative condition is hidradenitis suppurativa which is characterised by painful cysts that can ulcerate, and recur, and can become chronic lasting for many years.[82][83] Chronic cases can develop into squamous cell carcinomas.[83] An asymptomatic skin disorder of the vulval vestibule is vestibular papillomatosis which is characterised by fine, pink projections from either the epithelium of the vulva or from the labia minora. Dermatoscopy can distinguish this condition from genital warts.[84] A subtype of psoriasis, an autoimmune disease, is inverse psoriasis in which red patches can appear in the skin folds of the labia.[85]

Childbirth

The vulvar region is at risk for trauma during childbirth.[86] During childbirth, the vagina and vulva must stretch to accommodate the baby's head (approximately 9.5 cm (3.7 in)). This can result in tears known as perineal tears in the vaginal opening, and other structures within the perineum.[87] An episiotomy (a pre-emptive surgical cutting of the perineum) is sometimes performed to facilitate delivery and limit tearing. A tear takes longer to heal than an incision.[88] Tears and incisions may be repaired using sutures that may be layered.[89][2] Among the methods of hair removal evaluated for pre-surgeries, pubic hair shaving known as prepping, was seen to increase the risk of surgical site infections.[90][88] No advantages have been demonstrated in the routine shaving of pubic hair prior to childbirth.[91]

Surgery

Genitoplasties are plastic surgeries that can be carried out to repair, restore or alter vulvar tissues,[92] particularly following damage caused by injury or cancer treatment. These procedures include vaginoplasty which can also be performed as a cosmetic surgery. Other cosmetic surgeries to change the appearance of external structures include labiaplasties.[93] Some of these procedures, vaginoplasties and labiaplasties, are also carried out as sex reassignment surgeries.[94][95]

The use of cosmetic surgeries has been criticized by clinicians.[96][97] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women be informed of the risks of these surgeries. They refer to the lack of data relevant to their safety and effectiveness and to the potential associated risks such as infection, altered sensation, dyspareunia, adhesions, and scarring.[98] There is also a percentage of people seeking cosmetic surgery who may be suffering from body dysmorphic disorder and surgery in these cases can be counterproductive.[99]

Society and culture

Altering the female genitalia

In some cultural practices, particularly in the African Khoikhoi and Rwanda cultures, the labia minora are purposefully stretched by repeated pulling on them and sometimes by using attached weights.[100][101][13] Labia stretching is a recognised, familial cultural practice in parts of Eastern and Southern Africa.[100][102][103] This is a desired and encouraged practice by the women (starting at puberty) in order to promote better sexual satisfaction for both parties.[104][13] The achieved extensions can hang down below the labia majora for up to seven inches.[13]

In some cultures, including modern Western culture, women have shaved or otherwise removed the hair from part or all of the vulva. When high-cut swimsuits became fashionable, women who wished to wear them would remove the hair on either side of their pubic triangles, to avoid exhibiting pubic hair.[105] Other women relish the beauty of seeing their vulva with hair, or completely hairless, and find one or the other more comfortable. The removal of hair from the vulva is a fairly recent phenomenon in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe, usually in the form of bikini waxing or Brazilian waxing, but has been prevalent in many Eastern European and Middle Eastern cultures for centuries, usually due to the idea that it may be more hygienic, or originating in prostitution and pornography.[106][107] Hair removal may include all, most, or some of the hair.[108] French waxing leaves a small amount of hair on either side of the labia or a strip directly above and in line with the pudendal cleft called a landing strip.[108] Islam teaching includes Muslim hygienical jurisprudence a practice of which is the removal of pubic hair.[109]

Several forms of genital piercings can be made in the female genital area, and include the Christina piercing, the Nefertiti piercing, the fourchette piercing, and labia piercings. Piercings are usually performed for aesthetic purposes, but some forms like the clitoral hood piercing might also enhance pleasure during sex. Though they are common in traditional cultures, intimate piercings are a fairly recent trend in Western society.[110][111][112]

Female genital surgery includes laser resurfacing of the labia to remove wrinkles, labiaplasty (reducing the size of the labia) and vaginoplasty. In September 2007, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) issued a committee opinion on these and other female genital surgeries, including "vaginal rejuvenation", "designer vaginoplasty", "revirgination", and "G-spot amplification". This opinion states that the safety of these procedures has not been documented. The ACOG and the ISSVD recommend that women seeking these surgeries need to be informed about the lack of data supporting these procedures and the potential associated risks such as infection, altered sensation, dyspareunia, adhesions, and scarring.[98][113]

With the growing popularity of female cosmetic genital surgeries, the practice increasingly draws criticism from an opposition movement of cyberfeminist activist groups and platforms, called the labia pride movement. The major point of contention is that heavy advertising for these procedures, in combination with a lack of public education, fosters body insecurities in women with larger labia in spite of the fact that there is normal and pronounced individual variation in the size of labia. The preference for smaller labia is a matter of a fashion fad and is without clinical or functional significance.[114][115]

The most prevalent form of non-consensual genital alteration is that of female genital mutilation. This mostly involves the partial or complete removal of genital organs.[116] Female genital mutilation is carried out in thirty countries in Africa, and Asia with more than 200 million girls being affected, and some women (as of 2018).[116] Nearly all of the procedures are carried out on young girls. The practices are also carried out globally among migrants from these areas. Female genital mutilation is claimed to be mostly carried out for cultural traditional reasons.[116]

Etymology

The word vulva is Latin for "womb". It derives from the 1540s in referring to the womb and female sexual organs, from the earlier volvere meaning to turn, roll or revolve, with further derivatives such as used in volvox, and volvulus (twisted bowel).[117][118] The naming of the female (and male) genitals as pudenda membra, meaning parts to be ashamed of, dates from the mid-17th century.[119] The naming influenced the general perception of the vulva and this is shown in depicted gynaecological procedures. The examiner shown in the Obstetrical examination dated 1822, is adopting the compromise procedure where the woman's genitals cannot be seen.[120][121]

Alternative terms

There are many sexual slang terms used for the vulva.[122][123] Cunt, a medieval word for the vulva and once the standard term, has become a vulgarism, and in other uses one of the strongest offensive and abusive swearwords in English-speaking cultures. The word has been replaced in normal usage by a few euphemisms including pussy (vulgar slang) and fanny (UK) which used to be a common pet name.[124][122] In the UK these terms have other non-sexual meanings that lend themselves to double entendres, such as pussy which is used as a term of endearment for a pet cat – pussy cat.[125][126][127] In North American informal use the term pussy can also refer to a weak or effeminate man,[128] and fanny is a term used for the buttocks.[129][122] Other slang terms are muff, snatch, twat, and crotch.[130][131] Vagina is often used as a synonym for vulva even though it is a separate part of the anatomy.[132]

Religion and art

Some cultures have long celebrated and even worshipped the vulva. During the Uruk period (c. 4000–3100 BC), the ancient Sumerians regarded the vulva as sacred[133][134] and a vast number of Sumerian poems praising the vulva of Inanna, the goddess of love, sex, and fertility, have survived.[134] In Sumerian religion, the goddess Nin-imma is the divine personification of female genitalia.[135][136] Vaginal fluid is always described in Sumerian texts as tasting "sweet"[134] and, in a Sumerian bridal hymn, a young maiden rejoices that her vulva has grown hair.[134] Clay models of vulvas were discovered in the temple of Inanna at Ashur.[137]

Some major Hindu traditions such as Shaktism, a goddess-centred tradition, revere the vulva and vagina under the name yoni.[138][139] The goddess as Devi is worshipped as the supreme deity.[140] The yoni is a representation of the female deity and is found in many temples as a focus for prayer and offerings.[139] It is also represented symbolically as a mudra in spiritual practices, including yoga.[141]

Similar claims have been for pre-Islamic worship of the Black Stone,[142] in the Kaaba of Islam, there have also been disputes as to which goddess it was associated with.[143][144]

Sheela na gigs are figurative carvings of naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva. They are found in ancient and medieval European contexts. They are displayed on many churches, but their origin and significance is debatable. A main line of thinking is that they were used to ward off evil spirits. Another view is that the sheela na gig was a divine assistant in childbirth.[145][146] Starr Goode explores the image and possible meanings of the Sheela na gig and Baubo images in particular, but writes also about the recurring image worldwide. Through hundreds of photographs, she demonstrates that the image of a female displaying her vulva is not specific to European religious art or architecture, but that similar images are found in the visual arts and in mythical narratives of goddesses and heroines parting their thighs to reveal what she calls, "sacred powers." Her theory is that "the image is so rooted in our psyches that it seems as if the icon is the original cosmological center of the human imagination."[147]

L'Origine du monde ("Origin of the world") painted by Gustave Courbet in 1866 was an early Realist painting of a vulva that only became exhibited many years later.[148]

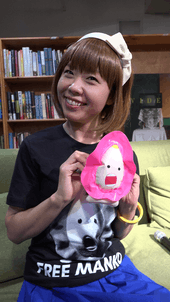

Japanese sculptor and manga artist Megumi Igarashi has focused much of her work on painting and modelling vulvas and vulva-themed works. She has used molds to create dioramas – three-dimensional models of her vulva with the hope of demystifying the female genitals.[149]

An art installation called The Dinner Party by feminist artist, Judy Chicago, portrays a symbolic history of famous women. The dinner plates each depict an elaborate vulval form and they are arranged in a triangular vulva shape.[150] Another installation was made by British artist Jamie McCartney who used the casts of four hundred vulvas to create The Great Wall of Vagina in 2011. The vagina casts are life-size. Explanations written by the project's sexual health adviser accompany these. The purpose of the artist was to "address some of the stigmas and misconceptions that are commonplace".[151][16]

Additional images

Vulva handsign used as a yogic mudra

Vulva handsign used as a yogic mudra Attic red-figure lid. Three female organs and a winged phallus.

Attic red-figure lid. Three female organs and a winged phallus..jpg) Yoni at Mahadev temple

Yoni at Mahadev temple

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1264 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Tortora, Gerard J; Derrickson, Bryan (2008). Principles of anatomy and physiology (12th ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. pp. 1107–1110. ISBN 9780470233474.

- Tortora, Gerard J; Anagnostakos, Nicholas P (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 727–728. ISBN 978-0060466695.

- "Anatomy and Physiology of the Female Reproductive System · Anatomy and Physiology". Phil Schatz.com.

- Stevenson, Angus; Lindberg, Christine A., eds. (2010). New Oxford American Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195392883.

The rounded mass of fatty tissue lying over the joint of the pubic bones, in women typically more prominent and also called the mons Veneris.

- Gould, George Milbry (1894). An Illustrated Dictionary of Medicine, Biology and Allied Sciences. London: Balliére, Tindall & Cox. pp. 649, 684, 778–779, 1212, 1610. OCLC 1045367748.

- Hennekam, RC; Allanson, JE; Biesecker, LG; Carey, JC; Opitz, JM; Vilain, E (June 2013). "Elements of morphology: standard terminology for the external genitalia". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 161A (6): 1238–63. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.35934. PMC 4440541. PMID 23650202.

- Marshall, WA; Tanner, JM (June 1969). "Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 44 (235): 291–303. doi:10.1136/adc.44.235.291. PMC 2020314. PMID 5785179.

- Pocock, Gillian; Richards, Christopher D. (2006). Human physiology : the basis of medicine (3rd. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 438. ISBN 9780198568780.

- Tortora, Gerard J; Derrickson, Bryan (2008). Principles of anatomy and physiology (12th ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. pp. 235–236. ISBN 9780470233474.

- Burrows (7 October 2009). 100 Questions & Answers About Vulvar Cancer and Other Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9781449630911. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Neill, Sallie; Lewis, Fiona (6 July 2009). Ridley's The Vulva. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444316698. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Young, Barbra; Lowe, James S; Stevens, Alan; Heath, John W; Deakin, Philip J (March 2006). Wheater's Functional Histology (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 175–178. ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

- King, Bruce M. (1996). Human sexuality today (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall. pp. 24–28. ISBN 978-0130149947.

- Fahmy, Mohamed (27 November 2014). Rare Congenital Genitourinary Anomalies: An Illustrated Reference Guide. Springer. ISBN 9783662436806. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- O'Connell, HE; Sanjeevan, KV; Hutson, JM (October 2005). "Anatomy of the clitoris". The Journal of Urology. 174 (4 Pt 1): 1189–95. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd. PMID 16145367.

- "'The Great Wall Of Vagina' Is, Well, A Great Wall Of Vaginas (NSFW)". Huffington Post. HuffPost. 8 January 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Wilkinson, Edward J. (2012). Wilkinson and Stone Atlas of Vulvar Disease (3rd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 187–188. ISBN 9781451132182.

- Lee, MY; Dalpiaz, A; Schwamb, R; Miao, Y; Waltzer, W; Khan, A (May 2015). "Clinical Pathology of Bartholin's Glands: A Review of the Literature". Current Urology. 8 (1): 22–5. doi:10.1159/000365683. PMC 4483306. PMID 26195958.

- Zaviacic M, Ablin RJ (January 2000). "The female prostate and prostate-specific antigen. Immunohistochemical localization, implications of this prostate marker in women and reasons for using the term "prostate" in the human female". Histol. Histopathol. 15 (1): 131–42. PMID 10668204.

- Raizada, V; Mittal, RK (September 2008). "Pelvic floor anatomy and applied physiology". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 37 (3): 493–509, vii. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.003. PMC 2617789. PMID 18793993.

- Maclean, Allan; Reid, Wendy (2011). "40". In Shaw, Robert (ed.). Gynaecology. Edinburgh New York: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 599–612. ISBN 978-0-7020-3120-5.

- Puppo, V (January 2013). "Anatomy and physiology of the clitoris, vestibular bulbs, and labia minora with a review of the female orgasm and the prevention of female sexual dysfunction". Clinical Anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 26 (1): 134–52. doi:10.1002/ca.22177. PMID 23169570.

- Albert, Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 140. ISBN 9781416062578.

- Albert, Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 2043. ISBN 9781416062578.

- "Superficial Inguinal Lymph Nodes — Medical Definition". www.medilexicon.com. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Albert, Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 1256–1257. ISBN 9781416062578.

- Oakley, SH; Mutema, GK; Crisp, CC; Estanol, MV; Kleeman, SD; Fellner, AN; Pauls, RN (September 2013). "Innervation and histology of the clitoral-urethal complex: a cross-sectional cadaver study". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 10 (9): 2211–8. doi:10.1111/jsm.12230. PMID 23809460.

- Albert, Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 1255. ISBN 9781416062578.

- Yucel, S; De Souza A, Jr; Baskin, LS (July 2004). "Neuroanatomy of the human female lower urogenital tract". The Journal of Urology. 172 (1): 191–5. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000128704.51870.87. PMID 15201770.

- "Clinical Case - Perineum & External Genitalia". The University of Michigan. 27 February 2009. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Hoffman, Barbara; et al. (2011). Williams gynecology (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 794–806. ISBN 9780071716727.

- Chung, Kyung Won (2005). Gross anatomy (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-7817-5309-8.

- Sadler, T. (2010). Langman's medical embryology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 253–258. ISBN 9780781790697.

- Larsen, William J. (2001). Human embryology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 284–288. ISBN 978-0443065835.

- "Hormonal effects in newborns: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". MedlinePlus. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Puppo, V (January 2011). "Embryology and anatomy of the vulva: the female orgasm and women's sexual health". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 154 (1): 3–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.08.009. PMID 20832160.

- "NHS Direct Wales - Encyclopaedia : Labial fusion". NHS Direct Wales. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Campbell, Neil (1990). Biology (2nd ed.). Redwood City, Calif.: Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co. pp. 939–946. ISBN 978-0805318005.

- Hall, John E (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 993–1000. ISBN 9781416045748.

- "Secondary Characteristics". hu-berlin.de. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- Ibáñez, L; Potau, N; Dunger, D; de Zegher, F (2000). "Precocious pubarche in girls and the development of androgen excess". Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 13 Suppl 5: 1261–3. PMID 11117666.

- "Sweating and body odor: Causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- "Pheromones Sex attraction" (PDF). Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- Lloyd, Jillian (May 2005). "Female genital appearance: 'normality' unfolds". British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 112 (5): 643–646. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.585.1427. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00517.x. PMID 15842291.

- Pocock, Gillian; Richards, Christopher D. (2006). Human physiology : the basis of medicine (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 446. ISBN 9780198568780.

- Vanessa Ngan (2002). "Vulval and vaginal problems in prepubertal females". DermNet NZ. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Goldstein, S. (2004). Pediatric and adolescent gynecology (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 120–155. ISBN 978-0781744935.

- Hall, John, E (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 1008–1014. ISBN 9781416045748.

- Faubion, Stephanie S.; Sood, Richa; Kapoor, Ekta (December 2017). "Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: Management Strategies for the Clinician; Concise Review for Physicians". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 92 (12): 1842–1849. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.019. PMID 29202940.

- "Definition of SMEGMA". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Fox, Kent M.; Van De Graaff, Stuart Ira (1989). Concepts of human anatomy and physiology (2nd ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Wm. C. Brown Publishers. pp. 958–963. ISBN 978-0697056757.

- Basson, R (January–March 2000). "The female sexual response: a different model". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 26 (1): 51–65. doi:10.1080/009262300278641. PMID 10693116.

- "Thrush in men and women". NHS UK. 9 January 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Mastromarino, Paola; Vitali, Beatrice; Mosca, Luciana (2013). "Bacterial vaginosis: a review on clinical trials with probiotics" (PDF). New Microbiologica. 36 (3): 229–238. PMID 23912864.

- Rimoin, Lauren P.; Kwatra, Shawn G.; Yosipovitch, Gil (2013). "Female-specific pruritus from childhood to postmenopause: clinical features, hormonal factors, and treatment considerations". Dermatologic Therapy. 26 (2): 157–167. doi:10.1111/dth.12034. ISSN 1396-0296. PMID 23551372.

- "Vaginitis - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "Pubic Hair Removal - Shaving". Palo Alto Medical Foundation. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Panagiotopoulou, N; Wong, CS; Winter-Roach, B (April 2010). "Vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 30 (3): 226–30. doi:10.3109/01443610903477572. PMID 20373919.

- Schlosser, BJ (May–June 2010). "Lichen planus and lichenoid reactions of the oral mucosa". Dermatologic Therapy. 23 (3): 251–67. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01322.x. PMID 20597944.

- "CDC - What Are the Symptoms of Vaginal and Vulvar Cancers?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Leone, PA (1 April 2007). "Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 Suppl 3: S153–9. doi:10.1086/511428. PMID 17342668.

- "Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) Fact sheet N°110". WHO. November 2013. Archived from the original on 25 November 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "safe sex | Definition of safe sex in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "Syphilis - CDC Fact Sheet (Detailed)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 November 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- "STD Facts - Gonorrhea". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Milner, Danny A. (3 June 2015). Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323400374.

- "Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer". WHO. June 2016. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016.

- "Genital Herpes – CDC Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Zweizig, Susan; Korets, Sharmilee; Cain, Joanna M. (2014). "Key concepts in management of vulvar cancer". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 28 (7): 959–966. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.07.001. ISSN 1521-6934. PMID 25151473.

- Stock, I (August 2013). "[Molluscum contagiosum--a common but poorly understood "childhood disease" and sexually transmitted illness]". Medizinische Monatsschrift Fur Pharmazeuten. 36 (8): 282–90. PMID 23977728.

- "Risk Factors - Molluscum Contagiosum". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- de Waaij, DJ; Dubbink, JH; Ouburg, S; Peters, RPH; Morré, SA (8 October 2017). "Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis infection and protozoan load in South African women: a cross-sectional study". BMJ Open. 7 (10): e016959. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016959. PMC 5640031. PMID 28993385.

- "STD Facts - Trichomoniasis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "About vulval cancer". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "Types of vulval cancer". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Fuh, KC; Berek, JS (February 2012). "Current management of vulvar cancer". Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 26 (1): 45–62. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2011.10.006. PMID 22244661.

- Hillemanns, P; Wang, X; Staehle, S; Michels, W; Dannecker, C (February 2006). "Evaluation of different treatment modalities for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN): CO(2) laser vaporization, photodynamic therapy, excision and vulvectomy". Gynecologic Oncology. 100 (2): 271–5. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.012. PMID 16169064.

- Amanda Oakley (2011). "Labial adhesion in prepubertal girls". Hamilton, New Zealand: DermNet NZ. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Feldhaus-Dahir, M (2011). "The causes and prevalence of vestibulodynia: A vulvar pain disorder". Urologic Nursing. 31 (1): 51–4. doi:10.7257/1053-816X.2012.31.1.51. PMID 21542444.

- Bergeron, S; Binik, YM; Khalifé, S; Pagidas, K (March 1997). "Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: a critical review". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 13 (1): 27–42. doi:10.1097/00002508-199703000-00006. PMID 9084950.

- Barret, Maximilien; de Parades, Vincent; Battistella, Maxime; Sokol, Harry; Lemarchand, Nicolas; Marteau, Philippe (2014). "Crohn's disease of the vulva". Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 8 (7): 563–570. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.10.009. ISSN 1873-9946. PMID 24252167.

- Stewart, KMA (September 2017). "Challenging Ulcerative Vulvar Conditions: Hidradenitis Suppurativa, Crohn Disease, and Aphthous Ulcers". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 44 (3): 453–473. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2017.05.009. PMID 28778643.

- Talmant, JC; Bruant-Rodier, C; Nunziata, AC; Rodier, JF; Wilk, A (February 2006). "[Squamous cell carcinoma arising in Verneuil's disease: two cases and literature review]". Annales de Chirurgie Plastique et Esthetique. 51 (1): 82–6. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2005.11.002. PMID 16488526.

- Kim, SH; Seo, SH; Ko, HC; Kwon, KS; Kim, MB (February 2009). "The use of dermatoscopy to differentiate vestibular papillae, a normal variant of the female external genitalia, from condyloma acuminate". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 60 (2): 353–5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.08.031. PMID 19150287.

- Weigle, N; McBane, S (1 May 2013). "Psoriasis". American Family Physician. 87 (9): 626–33. PMID 23668525.

- Dudley, Lynn M; Kettle, Christine; Ismail, Khaled MK; Dudley, Lynn M (2013). "Secondary suturing compared to non-suturing for broken down perineal wounds following childbirth" (PDF). Cochrane Database Syst Rev (9): CD008977. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008977.pub2. PMID 24065561.

- Finn, Martha; Bowyer, Lucy; Carr, Sandra; O'Connor, Vivienne; Vollenhoven, Beverley (2005). Women's Health: A Core Curriculum. Australia: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7295-3736-0.

- King, Bruce (1996). Human sexuality today (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall. p. 178. ISBN 978-0130149947.

- "Perineal Trauma: Assessment and Repair". the women's. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- Lefebvre, A.; Saliou, P.; Lucet, J.C.; Mimoz, O.; Keita-Perse, O.; Grandbastien, B.; Bruyère, F.; Boisrenoult, P.; Lepelletier, D.; Aho-Glélé, L.S. (2015). "Preoperative hair removal and surgical site infections: network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Hospital Infection. 91 (2): 100–108. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.06.020. ISSN 0195-6701. PMID 26320612.

- Basevi, Vittorio; Lavender, Tina; Basevi, Vittorio (2014). "Routine perineal shaving on admission in labour". Reviews (11): CD001236. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001236.pub2. PMID 25398160.

- "genitoplasty". TheFreeDictionary. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Wong, CS; Bhimji, SS (January 2018). "Labiaplasty, Labia Minora Reduction". PMID 28846226. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Munro, Donald. "Trans Media Watch". Trans Media Watch. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Carroll, Lynne; Mizock, Lauren (7 February 2017). Clinical Issues and Affirmative Treatment with Transgender Clients, An Issue of Psychiatric Clinics of North America, E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323510042. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Bourke, Emily (12 November 2009). "Designer vagina craze worries doctors". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- Liao, Lih Mei; Sarah M Creighton (24 May 2007). "Requests for cosmetic genitoplasty: how should healthcare providers respond?". BMJ. 334 (7603): 1090–1092. doi:10.1136/bmj.39206.422269.BE. PMC 1877941. PMID 17525451. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2007). "Vaginal "Rejuvenation" and Cosmetic Vaginal Procedures" (PDF): 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Tignol, J; Martin-Guehl, C; Aouizerzate, B (January 2012). "[Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD)]". Presse Médicale. 41 (1): e22–35. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2011.05.021. PMID 21831574.

- "Rwandan Women View The Elongation Of Their Labia As Positive". Medical News Today. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Wit over zwart · dbnl". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- Martínez Pérez, G; Mubanga, M; Tomás Aznar, C; Bagnol, B (2015). "Zambian Women in South Africa: Insights Into Health Experiences of Labia Elongation". Journal of Sex Research. 52 (8): 857–67. doi:10.1080/00224499.2014.1003027. PMID 26147362.

- Audet, CM; Blevins, M; Cherry, CB; González-Calvo, L; Green, AF; Moon, TD (May 2017). "Understanding intra-vaginal and labia minora elongation practices among women heads-of-households in Zambézia Province, Mozambique". Culture, Health & Sexuality. 19 (5): 616–629. doi:10.1080/13691058.2016.1257739. PMC 5460297. PMID 27921861.

- "Health and beauty: vaginal practices: Indonesia (Yogyakarta), Mozambique (Tete), South Africa (KwaZulu-Natal), and Thailand (Chonburi)" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Tschachler, Heinz; Devine, Maureen; Draxlbauer, Michael (2003). The EmBodyment of American Culture. Berlin-Hamburg-Münster: LIT Verlag. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-3-8258-6762-1.

- Rowen TS; Gaither TW; Awad MA; Osterberg E; Shindel AW; Breyer BN (October 2016). "Pubic Hair Grooming Prevalence and Motivation Among Women in the United States" (PDF). JAMA Dermatology. 152 (10): 1106–1113. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2154. ISSN 2168-6068. PMID 27367465.

- Farage, Miranda A.; Maibach, Howard I. (19 April 2016). The Vulva: Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420005318. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Helen Bickmore; Milady's Hair Removal Techniques: A Comprehensive Manual; Thomson Delmar Learning; 2003; ISBN 1-4018-1555-3

- Ismail, Buyukcelebi (2003). Living in the Shade of Islam: A Comprehensive Reference of Theory and Practice. Tughra Books. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-932-09921-8.

- "Can selfish lovers ever give as good as they get? Plus, the perks of piercings and how to get her to hurry up already". MSNBC. 4 December 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Millner, Vaughn S.; Eichold, Bernard H.; Sharpe, Thomasina H.; Lynn, Sherwood C. (2005). "First glimpse of the functional benefits of clitoral hood piercings". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 193 (3): 675–676. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.130. PMID 16150259. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "VCH Piercings, by Elayne Angel, Seite 16-17, The Official Newsletter of The Association of Professional Piercers" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Vieira-Baptista, Pedro; Almeida, Gutemberg; Bogliatto, Fabrizio; Bohl, Tanja Gizela; Burger, Matthé; Cohen-Sacher, Bina; Gibbon, Karen; Goldstein, Andrew; Heller, Debra (July 2018). "International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Recommendations Regarding Female Cosmetic Genital Surgery". Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 22 (4): 415–434. doi:10.1097/lgt.0000000000000412. ISSN 1526-0976. PMID 29994815.

- Clark-Flory, Tracy (17 February 2013). "The "labia pride" movement: Rebelling against the porn aesthetic, women are taking to the Internet to sing the praises of "endowed" women". Salon.com. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- Sourdès, Lucile (21 February 2013). "Révolution vulvienne: Contre l'image de la vulve parfaite, elles se rebellent sur Internet". Rue89. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- "Female genital mutilation". World Health Organization. 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "Vulva | Define Vulva at Dictionary.com".

- "vulva - Search Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- Dictionaries, Oxford (10 May 2012). Paperback Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199640942. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "Women's problems in early 1800s". Bronwen Evans. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Balayla, J (June 2011). "Male physicians treating Female patients: Issues, Controversies and Gynecology". McGill Journal of Medicine : MJM : An International Forum for the Advancement of Medical Sciences by Students. 13 (1): 72. PMC 3296153. PMID 22399872.

- "vulva | Search Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- For slang terms for the vulva, see WikiSaurus:female genitalia — the WikiSaurus list of synonyms and slang words for female genitalia in many languages.

- A Dictionary of First Names (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Pet form of Frances, very popular in the 18th and 19th centuries, but now much rarer

- Silverton, Peter (2011). Filthy English: The How, Why, When And What Of Everyday Swearing. Granta Publications. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-84627-452-7. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Rosewarne, Lauren (2013). American Taboo: The Forbidden Words, Unspoken Rules, and Secret Morality of Popular Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-313-39934-3.

While pussy as a euphemism for vagina is very common in popular parlance, Mrs Slocombe was actually talking about her pet cat. In this context, the use of pussy works as a double entendre rather than as a euphemism.

- Jeffries, Stuart (2008). Mrs Slocombe's Pussy: Growing Up in Front of the Telly. Flamingo.

Mrs Slocombe's pussy changed all that.[...]It was funny, surely, because it dissolved that secret source of female power into a double entendre.

- "pussy | Definition of pussy in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English.

- "fanny | Definition of fanny in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English.

- Hollander, Anne (22 March 1993). Seeing Through Clothes. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520082311.

- "vagina | Synonyms of vagina by Oxford Dictionaries Thesaurus". Oxford Dictionaries | %{language.}

- "What are the parts of the female sexual anatomy?". Planned Parenthood. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Dening, Sarah (1996). "Chapter 3: Sex in Ancient Civilizations". The Mythology of Sex. London, England: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-861207-2.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2013) [1994]. Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature. New York: Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-134-92074-7.

- Ceccarelli, Manuel (2016). Enki und Ninmah: Eine mythische Erzählung in sumerischer Sprache. Orientalische Relionen in der Antik. 16. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-16-154278-7.

- Launderville, Dale (2010). Celibacy in the Ancient World: Its Ideal and Practice in Pre-Hellenistic Israel, Mesopotamia, and Greece. A Michael Glazier Book. Collegeville, Maryland: Liturgical Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-8146-5734-8.

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8.

- "Yoni". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "Yoni". Yoni - Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. January 2009. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198610250.001.0001. ISBN 9780198610250. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Flood, Gavin D. (13 July 1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521438780. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Mudra Photo Gallery". Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- University of Southern California. "The Prophet of Islam – His Biography". Archived from the original on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- Tate, Karen (1 January 2006). Sacred Places of Goddess: 108 Destinations. San Francisco: Consortium of Collective Consciousness Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 9781888729115.

- Camphausen, Rufus (1996). The Yoni, Sacred Symbol of Female Creative Power. Vermont: Inner Traditions. Bear & Company. p. 134. ISBN 9780892815623.

- Freitag, Barbara (2004). Sheela-na-gigs: Unravelling an Enigma. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415345521. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- Andersen, Jørgen (1977). The witch on the wall : medieval erotic sculpture in the British isles. Copenhagen: Roskilde & Bagger. ISBN 978-87-423-0182-1.

- Goode, Staff (2016). Sheela na gig: The Dark Goddess of Sacred Power. Inner Traditions. ISBN 9781620555958. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- "Musée d'Orsay: Gustave Courbet The Origin of the World". Musée d'Orsay. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- McCurry, Justin (15 July 2014). "Vagina selfie for 3D printers lands Japanese artist in trouble". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Woodman, Judy Chicago; photography by Donald (2007). The dinner party : from creation to preservation. London: Merrell Publishers. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-85894-370-1.

- McCartney, Jamie (2011). The great wall of vagina. Brighton: Jamie McCartney. ISBN 978-0956878502.

External links

| Look up vulva in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- 'V' is for vulva, not just vagina by Harriet Lerner discussing common misuse of the word "vagina"

- Vulvar hygiene and Urinary Tract Infections by Heather Corinna (illustrations; no explicit photos)