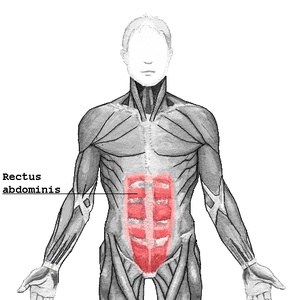

Rectus abdominis muscle

The rectus abdominis muscle, also known as the "abdominal muscle" or "abs", is a paired muscle running vertically on each side of the anterior wall of the human abdomen, as well as that of some other mammals. There are two parallel muscles, separated by a midline band of connective tissue called the linea alba. It extends from the pubic symphysis, pubic crest and pubic tubercle inferiorly, to the xiphoid process and costal cartilages of ribs V to VII superiorly.[1] The proximal attachments are the pubic crest and the pubic symphysis. It attaches distally at the costal cartilages of ribs 5-7 and the xiphoid process of the sternum.[2]

| Rectus abdominis | |

|---|---|

The human rectus abdominis muscle. | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Crest of pubis |

| Insertion | costal cartilages of ribs 5-7 Xiphoid process of sternum. |

| Artery | inferior epigastric artery |

| Nerve | segmentally by thoraco-abdominal nerves (T7 to T11) and subcostal (T12) |

| Actions | Flexion of the lumbar spine |

| Antagonist | Erector spinae |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus rectus abdominis |

| MeSH | D017568 |

| TA | A04.5.01.001 |

| FMA | 9628 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The Abdominalus Sucurum is contained in the rectus sheath, which consists of the aponeuroses of the lateral abdominal muscles. Bands of connective tissue called the tendinous intersections traverse the rectus abdominis, which separates this parallel muscle into distinct muscle bellies. The outer, most lateral line, defining the "abs" is the linea semilunaris. In the abdomens of people with low body fat, these muscle bellies can be viewed externally and are commonly referred to as "four", "six", "eight", or "ten packs", depending on how many are visible; although, six is the most common.

Structure

The rectus abdominis is a long flat muscle, which extends along the whole length of the front of the abdomen, and is separated from its fellow of the opposite side by the linea alba. Tendinous intersections (incriptiones tendinae) further subdivide each rectus abdominis muscle into a series of smaller false muscle bellies. Tensing of the rectus abdominis causes the muscle to expand between each tendinous intersection, resulting in the characteristic six or eight pack observed in individuals with low body fat.[3]

The upper portion, attached principally to the cartilage of the fifth rib, usually has some fibers of insertion into the anterior extremity of the rib itself.

Size

It is typically around 10 mm thick (compared to 20 mm thick superficial fat),[4] or 20 mm thick in young athletes such as handball players.[5] Typical volume is around 300 cm³ in non-active individuals, or almost 500 cm³ in athletes (tennis players).[6]

Blood supply

The rectus abdominis has many sources of arterial blood supply. Classification of the vascular anatomy of muscles: First, the inferior epigastric artery and vein (or veins) run superiorly on the posterior surface of the rectus abdominis, enter the rectus fascia at the arcuate line, and serve the lower part of the muscle. Second, the superior epigastric artery, a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery, supplies blood to the upper portion. Finally, numerous small segmental contributions come from the lower six intercostal arteries as well.

Nerve supply

The muscles are innervated by thoraco-abdominal nerves, these are continuations of the T7-T11 intercostal nerves and pierce the anterior layer of the rectus sheath. Sensory supply is from the 7-12 thoracic nerves

Variation

The sternalis muscle may be a variant form of the pectoralis major or the rectus abdominis. Some fibers are occasionally connected with the costoxiphoid ligaments, and the side of the xiphoid process.

Function

The rectus abdominis is an important postural muscle. It is responsible for flexing the lumbar spine, as when doing a so-called "crunch" sit up. The rib cage is brought up to where the pelvis is when the pelvis is fixed, or the pelvis can be brought towards the rib cage (posterior pelvic tilt) when the rib cage is fixed, such as in a leg-hip raise. The two can also be brought together simultaneously when neither is fixed in space.

The rectus abdominis assists with breathing and plays an important role in respiration when forcefully exhaling, as seen after exercise as well as in conditions where exhalation is difficult such as emphysema. It also helps in keeping the internal organs intact and in creating intra-abdominal pressure, such as when exercising or lifting heavy weights, during forceful defecation or parturition (childbirth).

Clinical significance

An abdominal muscle strain, also called a pulled abdominal muscle, is an injury to one of the muscles of the abdominal wall. A muscle strain occurs when the muscle is stretched too far. When this occurs the muscle fibers are torn. Most commonly, a strain causes microscopic tears within the muscle, but occasionally, in severe injuries, the muscle can rupture from its attachment.

A rectus sheath hematoma is an accumulation of blood in the sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle. It causes abdominal pain with or without a mass. The hematoma may be caused by either rupture of the epigastric artery or by a muscular tear. Causes of this include anticoagulation, coughing, pregnancy, abdominal surgery and trauma. With an ageing population and the widespread use of anticoagulant medications, there is evidence that this historically benign condition is becoming more common and more serious.[7]

On abdominal examination, people may have a positive Carnett's sign.

Most hematomas resolve without treatment, but they may take several months to resolve.

Other animals

The rectus abdominis is similar in most vertebrates. The most obvious difference between animal and human abdominal musculature is that in animals, there are a different number of tendinous intersections.

Additional images

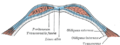

Diagram of sheath of rectus

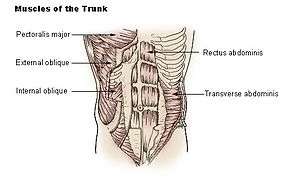

Diagram of sheath of rectus Muscles of the trunk

Muscles of the trunk Example of a man with a visible rectus abdominis

Example of a man with a visible rectus abdominis

References

- Gray's Anatomy for students, 2nd edition, Page:176

- "Rectus Abdominis Muscle | Actions | Attachments | Origin & Insertion". www.getbodysmart.com. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- Abdomen, in Moore, K.L., Dalley, A.F., Agur, A.M.R. (eds). 2014. Clinically Oriented Anatomy: Seventh Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia. PA. pg:191.

- Thickness of the rectus abdominis muscle and the abdominal subcutaneous fat tissue. Kim, Jungmin; Lim, Hyoseob; Lee, Se Il; Kim, Yu Jin (2012). "Thickness of Rectus Abdominis Muscle and Abdominal Subcutaneous Fat Tissue in Adult Women: Correlation with Age, Pregnancy, Laparotomy, and Body Mass Index". Archives of Plastic Surgery. 39 (5): 528–33. doi:10.5999/aps.2012.39.5.528. PMC 3474411. PMID 23094250.

- Anteroposterior diameter comparison of dominant (D) and nondominant (ND) rectus abdominis in elite handball players. Pedret; Balius; Pacheco, Sra.; Gutierrez; Escoda; Vives (1 July 2011). "Rectus abdominis muscle injuries in elite handball players: management and rehabilitation". Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 2: 69–73. doi:10.2147/oajsm.s17504. PMC 3781885. PMID 24198573. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Sanchis-Moysi, Joaquin; Idoate, Fernando; Dorado, Cecilia; Alayón, Santiago; Calbet, Jose A. L. (31 December 2010). "Large Asymmetric Hypertrophy of Rectus Abdominis Muscle in Professional Tennis Players". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e15858. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015858. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3013134. PMID 21209832.

- Fitzgerald, J. E. F.; Fitzgerald, L. A.; Anderson, F. E.; Acheson, A. G. (2009). "The changing nature of rectus sheath haematoma: Case series and literature review". International Journal of Surgery. 7 (2): 150–154. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.01.007. PMID 19261556.

External links

- Anatomy figure: 04:04-07 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Muscles of the anterior chest wall with the pectoralis major muscles removed."

- Anatomy photo:18:01-0115 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Thoracic Wall: The Anterior Thoracic Wall"

- Anatomy figure: 35:06-07 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Incision and reflection of the external abdominal oblique muscle."

- Anatomy figure: 35:07-01 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Incision and reflection of the internal abdominal oblique muscle."

- Anatomy photo:35:10-0100 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center – "Anterior Abdominal Wall: The Rectus Abdominis Muscle"

- Cross section image: pembody/body12a—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- "Anatomy diagram: 25466.180-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.