Fallopian tube

The Fallopian tubes, also known as uterine tubes or salpinges (singular salpinx) are uterine appendages. The name comes from the Catholic priest and anatomist Gabriele Falloppio for whom other anatomical structures are also named.

| Fallopian tube | |

|---|---|

Uterus and fallopian tubes | |

Cross-section of Fallopian tube, stained and viewed under microscope | |

| Details | |

| System | Reproductive system |

| Artery | tubal branches of ovarian artery, tubal branch of uterine artery via mesosalpinx |

| Lymph | lumbar lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Tuba uterina |

| Greek | Salpinx |

| MeSH | D005187 |

| TA | A09.1.02.001 |

| FMA | 18245 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Inside the Fallopian tubes there are hair-like Fallopian cilia which carry the fertilized egg from the ovaries of female mammals to the uterus, via the uterotubal junction. This tubal tissue is ciliated simple columnar epithelium. In non-mammalian vertebrates, the equivalent of a Fallopian tube is an oviduct.

Structure

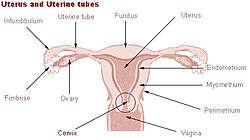

Its different segments are (lateral near the ovaries to medial near the uterus): the infundibulum with its associated fimbriae near the ovary, the ampullary region that represents the major portion of the lateral tube, the isthmus the visible medial third segment which is the narrower part of the tube that links to the uterus, and the interstitial (also known as intramural) part that transverses the uterine musculature. The ostium is the point where the tubal canal meets the peritoneal cavity, while the uterine opening of the fallopian tube is the entrance into the uterine cavity, the uterotubal junction. The average length of a fallopian tube is 11-12 cm.[1]

Microanatomy

A cross-section of a fallopian tube shows four distinct layers, from outer to inner: serosa, subserosa, lamina propria and innermost mucosal. The serosa is derived from visceral peritoneum. Subserosa is composed of loose adventitious tissue, blood vessels, lymphatics, an outer longitudinal and inner circular smooth muscle coats. This layer is responsible for the peristaltic action of the fallopian tubes. Lamina propria is a vascular connective tissue.[2]

The inner layer is a single layer of simple columnar epithelium. The columnar cells have microscopic hair-like filaments (cilia) predominately throughout the tube, but are most numerous in the infundibulum and ampulla. Estrogen increases the production of cilia on these cells. Between the ciliated cells are peg cells, which contain apical granules and produce the tubular fluid. This fluid contains nutrients for spermatozoa, oocytes, and zygotes. The secretions also promote capacitation of the sperm by removing glycoproteins and other molecules from the plasma membrane of the sperm. Progesterone increases the number of peg cells, while estrogen increases their height and secretory activity. Tubal fluid flows against the action of the cilia, that is toward the fimbrial end.

In view of longitudinal variation in histological features of tube, the isthmus has thick muscular coat and simple mucosal folds; whereas ampulla has complex mucosal folds.[2]

Development

Embryos have two pairs of ducts to let gametes out of the body; one pair (the Müllerian ducts) develops in females into the fallopian tubes, uterus and vagina, while the other pair (the Wolffian ducts) develops in males into the epididymis and vas deferens.

Normally, only one of the pairs of tubes will develop while the other regresses and disappears in utero.

The homologous organ in the male is the rudimentary appendix testis.

Function

Fertilization

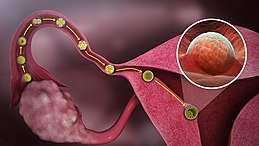

The tube allows passage of the egg from the ovary to the uterus. When an oocyte is developing in an ovary, it is encapsulated in a spherical collection of cells known as an ovarian follicle. Just prior to ovulation the primary oocyte completes meiosis I to form the first polar body and a secondary oocyte which is arrested in metaphase of meiosis II. This secondary oocyte is then ovulated. The follicle and the ovary's wall rupture, allowing the secondary oocyte to escape. The secondary oocyte is caught by the fimbriated end and travels to the ampulla of the uterine tube where typically the sperm are met and fertilization occurs; meiosis II is promptly completed. The fertilized ovum, now a zygote, travels towards the uterus aided by activity of tubal cilia and activity of the tubal muscle. The early embryo requires critical development in the fallopian tube.[3] After about five days the new embryo enters the uterine cavity and on about the sixth day implants on the wall of the uterus.

The release of an oocyte does not alternate between the two ovaries and seems to be random. After removal of an ovary, the remaining one produces an egg every month.[4]

Occasionally the embryo implants into the fallopian tube instead of the uterus, creating an ectopic pregnancy, commonly known as a "tubal pregnancy".

Clinical significance

Patency testing

While a full testing of tubal functions in patients with infertility is not possible, testing of tubal patency is important as tubal obstruction is a major cause of infertility. A hysterosalpingogram, laparoscopy and dye, or HyCoSy (hysterocontrast sonography) will demonstrate that tubes are open. Tubal insufflation is a standard procedure for testing patency. During surgery the condition of the tubes may be inspected and a dye such as methylene blue can be injected into the uterus and shown to pass through the tubes when the cervix is occluded. As tubal disease is often related to Chlamydia infection, testing for Chlamydia antibodies has become a cost-effective screening device for tubal pathology.[5]

Inflammation

Salpingitis is inflammation of the fallopian tubes and may be found alone, or be a component of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). A thickening of the fallopian tube at its narrow portion, due to inflammation, is known as salpingitis isthmica nodosa. Like PID and endometriosis, it may lead to fallopian tube obstruction. Fallopian tube obstruction is associated with infertility and ectopic pregnancy.[6]

Cancer

Fallopian tube cancer, which typically arises from the epithelial lining of the fallopian tube, has historically been considered to be a very rare malignancy. Recent evidence suggests it probably represents a significant portion of what has been classified as ovarian cancer in the past.[7] While tubal cancers may be misdiagnosed as ovarian cancer, it is of little consequence as the treatment of both ovarian and fallopian tube cancer is similar.

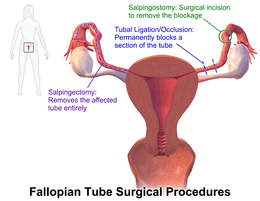

Surgery

The surgical removal of a fallopian tube is called a salpingectomy. To remove both tubes is a bilateral salpingectomy. An operation that combines the removal of a fallopian tube with removal of at least one ovary is a salpingo-oophorectomy. An operation to remove a fallopian tube obstruction is called a tuboplasty.

History

They are named after their discoverer, the 16th century Italian anatomist Gabriele Falloppio, who thought they resembled tubas, the plural of tuba in Italian being tube.[9]

Though the name Fallopian tube is eponymous, it is often spelt with a lower case f from the assumption that the adjective fallopian has been absorbed into modern English as the de facto name for the structure.

Additional images

Fallopian tube

Fallopian tube

See also

References

- Eddy, Carlton A; Pauerstein, Carl J (December 1980). "Anatomy and physiology of the fallopian tube". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 23 (4): 1177–93. doi:10.1097/00003081-198012000-00023. PMID 7004702.

- Daftary, Shirish; Chakravarti, Sudip (2011). Manual of Obstetrics (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-81-312-2556-1.

- Li, Shuai; Winuthayanon, Wipawee (January 2017). "Oviduct: roles in fertilization and early embryo development". Journal of Endocrinology. 232 (1): R1–R26. doi:10.1530/JOE-16-0302. PMID 27875265.

- "Menstrual Cycle: Biology of the Female Reproductive System: Merck Manual Home Health Handbook". Merck.com. Retrieved 2011-03-06.

- Kodaman PH, Arici A, Seli E (June 2004). "Evidence-based diagnosis and management of tubal factor infertility". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 16 (3): 221–9. doi:10.1097/00001703-200406000-00004. PMID 15129051.

- Salpingitis at eMedicine

- Hirst, Jane E.; Gard, Gregory B.; McIllroy, Kirsty; Nevell, David; Field, Michael (July 2009). "High Rates of Occult Fallopian Tube Cancer Diagnosed at Prophylactic Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 19 (5): 826–829. doi:10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a1b5dc. PMID 19574767.

- "Benign Neoplasms of the Vagina | GLOWM". www.glowm.com. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

- "A Medley of Maladies". QI. Series M. Episode 1. 16 October 2015. 0:38:37 minutes in. BBC Two. Transcript from Subsaga.com. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

He thought they reminded him of what were in those days rather long musical instruments with an end like a trumpet's bell, these were tubas. And so he called them tubas. And if you have a tuba, if you have a word ending in A in Italian, how do you pluralise it? What is two tuba? ... Tube. With an E on the end, spelled T-U-B-E. So, when it went around the world as his tube, his tubas, people saw the word tube. But, in fact, he had called them tubas.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fallopian tube. |

- Histology image: 18501loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Menstrual Cycle - Merck