Lymph

Lymph (from Latin, lympha meaning "water"[1]) is the fluid that flows through the lymphatic system, a system composed of lymph vessels (channels) and intervening lymph nodes whose function, like the venous system, is to return fluid from the tissues to the central circulation. Interstitial fluid – the fluid which is between the cells in all body tissues[2] – enters the lymph capillaries. This lymphatic fluid is then transported via progressively larger lymphatic vessels through lymph nodes, where substances are removed by tissue lymphocytes and circulating lymphocytes are added to the fluid, before emptying ultimately into the right or the left subclavian vein, where it mixes with central venous blood.

| Lymph | |

|---|---|

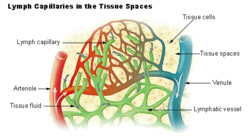

Diagram showing the formation of lymph from interstitial fluid (labeled here as "Tissue fluid"). Note how the tissue fluid is entering the blind ends of lymph capillaries (shown as deep green arrows) | |

| Details | |

| System | Lymphatic system |

| Source | Formed from interstitial fluid |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Lympha |

| MeSH | D008196 |

| TA | A12.0.00.043 |

| FMA | 9671 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Since the lymph is derived from the interstitial fluid, its composition continually changes as the blood and the surrounding cells continually exchange substances with the interstitial fluid. It is generally similar to blood plasma, which is the fluid component of blood. Lymph returns proteins and excess interstitial fluid to the bloodstream. Lymph also transports fats from the digestive system (beginning in the lacteals) to the blood via chylomicrons.

Bacteria may enter the lymph channels and be transported to lymph nodes, where they are destroyed. Metastatic cancer cells can also be transported via lymph.

Etymology

The word lymph is derived from the name of the ancient Roman deity of fresh water, Lympha.

Structure

Lymph has a composition similar but not identical to that of blood plasma. Lymph that leaves a lymph node is richer in lymphocytes than blood plasma is. The lymph formed in the human digestive system called chyle is rich in triglycerides (fat), and looks milky white because of its lipid content.

Development

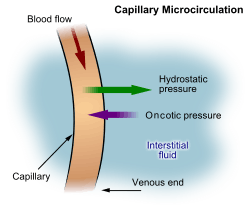

Blood supplies nutrients and important metabolites to the cells of a tissue and collects back the waste products they produce, which requires exchange of respective constituents between the blood and tissue cells. This exchange is not direct, but instead occurs through an intermediary called interstitial fluid, which occupies the spaces between cells. As the blood and the surrounding cells continually add and remove substances from the interstitial fluid, its composition continually changes. Water and solutes can pass between the interstitial fluid and blood via diffusion across gaps in capillary walls called intercellular clefts; thus, the blood and interstitial fluid are in dynamic equilibrium with each other.[3]

Interstitial fluid forms at the arterial (coming from the heart) end of capillaries because of the higher pressure of blood compared to veins, and most of it returns to its venous ends and venules; the rest (up to 10%) enters the lymph capillaries as lymph.[4] Thus, lymph when formed is a watery clear liquid with the same composition as the interstitial fluid. However, as it flows through the lymph nodes it comes in contact with blood, and tends to accumulate more cells (particularly, lymphocytes) and proteins.[5]

Function

Components

Lymph returns proteins and excess interstitial fluid to the bloodstream. Lymph may pick up bacteria and bring them to lymph nodes, where they are destroyed. Metastatic cancer cells can also be transported via lymph. Lymph also transports fats from the digestive system (beginning in the lacteals) to the blood via chylomicrons.

Circulation

Tubular vessels transport lymph back to the blood, ultimately replacing the volume lost during the formation of the interstitial fluid. These channels are the lymphatic channels, or simply lymphatics.[6]

Unlike the cardiovascular system, the lymphatic system is not closed and has no central pump, or lymph heart (which are found in some animals). Lymph transport, therefore, is slow and sporadic. Despite low pressure, lymph movement occurs due to peristalsis (propulsion of the lymph due to alternate contraction and relaxation of smooth muscle tissue), valves, and compression during contraction of adjacent skeletal muscle and arterial pulsation.[7]

Lymph that enters the lymph vessels from the interstitial spaces usually does not flow backwards along the vessels because of the presence of valves. If excessive hydrostatic pressure develops within the lymph vessels, though, some fluid can leak back into the interstitial spaces and contribute to formation of edema.

The flow of lymph in the thoracic duct in an average resting person usually approximates 100ml per hour. Accompanied by another ~25ml per hour in other lymph vessels, the total lymph flow in the body is about 4 to 5 litres per day. This can be elevated several fold while exercising. It is estimated that without lymphatic flow, the average resting person would die within 24 hours.[8]

Clinical significance

Histopathological examination of the lymph system is used as a screening tool for immune system analysis in conjunction with pathological changes in other organ systems and clinical pathology to assess disease status.[9] Although histological assessment of the lymph system does not directly measure immune function, it can be combined with identification of chemical biomarkers to determine underlying changes in the diseased immune system.[10]

As a growth medium

In 1907 the zoologist Ross Granville Harrison demonstrated the growth of frog nerve cell processes in a medium of clotted lymph. It is made up of lymph nodes and vessels.

In 1913, E. Steinhardt, C. Israeli, and R. A. Lambert grew vaccinia virus in fragments of tissue culture from guinea pig corneal grown in lymph.[11]

References

- "Lymph - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- Fluid Physiology: 2.1 Fluid Compartments

- "The Lymphatic System". Human Anatomy (Gray's Anatomy). Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- Warwick, Roger; Peter L. Williams (1973) [1858]. "Angiology (Chapter 6)". Gray's anatomy. illustrated by Richard E. M. Moore (Thirty-fifth ed.). London: Longman. pp. 588–785.

- Sloop, Charles H.; Ladislav Dory; Paul S. Roheim (March 1987). "Interstitial fluid lipoproteins" (PDF). Journal of Lipid Research. 28 (3): 225–237. PMID 3553402. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- "Definition of lymphatics". Webster's New World Medical Dictionary. MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- Shayan, Ramin; Achen, Marc G.; Stacker, Steven A. (2006). "Lymphatic vessels in cancer metastasis: bridging the gaps". Carcinogenesis. 27 (9): 1729–38. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgl031. PMID 16597644.

- Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology. Saunders. 2010. pp. 186, 187. ISBN 978-1416045748.

- Elmore, Susan A. (16 November 2011). "Enhanced histopathology of the immune system". Toxicologic Pathology. 40 (2): 148–156. doi:10.1177/0192623311427571. ISSN 0192-6233. PMC 3465566. PMID 22089843.

- Elmore, Susan A. (2018). "Enhanced Histopathology Evaluation of Lymphoid Organs". Methods in Molecular Biology. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1803. pp. 147–168. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-8549-4_10. ISBN 978-1-4939-8548-7. ISSN 1064-3745. PMID 29882138.

- Steinhardt, E; Israeli, C; and Lambert, R.A. (1913) "Studies on the cultivation of the virus of vaccinia" J. Inf Dis. 13, 294–300

External links