Plastic surgery

Plastic surgery is a surgical specialty involving the restoration, reconstruction, or alteration of the human body. It can be divided into two main categories: reconstructive surgery and cosmetic surgery. Reconstructive surgery includes craniofacial surgery, hand surgery, microsurgery, and the treatment of burns. While reconstructive surgery aims to reconstruct a part of the body or improve its functioning, cosmetic (or aesthetic) surgery aims at improving the appearance of it.[1] Both of these techniques are used throughout the world.

Etymology

The word plastic in plastic surgery means 'reshaping' and comes from the Greek πλαστική (τέχνη), plastikē (tekhnē), "the art of modelling" of malleable flesh.[2] This meaning in English is seen as early as 1598.[3] The surgical definition of "plastic" first appeared in 1839, preceding the modern "engineering material made from petroleum" sense by 70 years.[4]

History

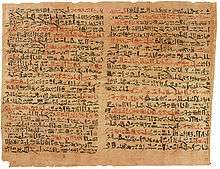

Treatments for the plastic repair of a broken nose are first mentioned in the Edwin Smith Papyrus,[6] a transcription of an Ancient Egyptian medical text, one of the oldest known surgical treatises, dated to the Old Kingdom from 3000 to 2500 BC.[7] Reconstructive surgery techniques were being carried out in India by 800 BC.[8] Sushruta was a physician who made important contributions to the field of plastic and cataract surgery in 6th century BC.[9] The medical works of both Sushruta and Charaka, originally in Sanskrit, were translated into the Arabic language during the Abbasid Caliphate in 750 AD.[10] The Arabic translations made their way into Europe via intermediaries.[10] In Italy, the Branca family[11] of Sicily and Gaspare Tagliacozzi (Bologna) became familiar with the techniques of Sushruta.[10]

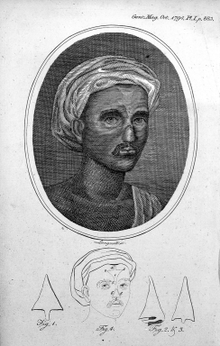

British physicians traveled to India to see rhinoplasties being performed by Indian methods.[12] Reports on Indian rhinoplasty performed by a Kumhar Vaidya were published in the Gentleman's Magazine by 1794.[12] Joseph Constantine Carpue spent 20 years in India studying local plastic surgery methods.[12] Carpue was able to perform the first major surgery in the Western world in the year of 1815.[13] Instruments described in the Sushruta Samhita were further modified in the Western world.[13]

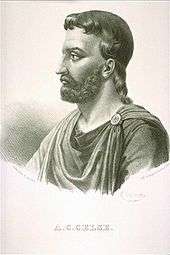

The Romans also performed plastic cosmetic surgery. The Romans were able to perform simple techniques, such as repairing damaged ears, from around the 1st century BC. For religious reasons, they did not dissect either human beings or animals, thus their knowledge was based in its entirety on the texts of their Greek predecessors. Notwithstanding, Aulus Cornelius Celsus left some surprisingly accurate anatomical descriptions,[14] some of which — for instance, his studies on the genitalia and the skeleton — are of special interest to plastic surgery.[15]

In 1465, Sabuncu's book, description, and classification of hypospadias was more informative and up to date. Localization of urethral meatus was described in detail. Sabuncuoglu also detailed the description and classification of ambiguous genitalia. In mid-15th-century Europe, Heinrich von Pfolspeundt described a process "to make a new nose for one who lacks it entirely, and the dogs have devoured it" by removing skin from the back of the arm and suturing it in place. However, because of the dangers associated with surgery in any form, especially that involving the head or face, it was not until the 19th and 20th centuries that such surgery became common.

Up until the use of anesthesia became established, surgeries involving healthy tissues involved great pain. Infection from surgery was reduced by the introduction of sterile techniques and disinfectants. The invention and use of antibiotics, beginning with sulfonamide and penicillin, was another step in making elective surgery possible.

In 1793, François Chopart performed operative procedure on a lip using a flap from the neck. In 1814, Joseph Carpue successfully performed operative procedure on a British military officer who had lost his nose to the toxic effects of mercury treatments. In 1818, German surgeon Carl Ferdinand von Graefe published his major work entitled Rhinoplastik. Von Graefe modified the Italian method using a free skin graft from the arm instead of the original delayed pedicle flap.

The first American plastic surgeon was John Peter Mettauer, who, in 1827, performed the first cleft palate operation with instruments that he designed himself. In 1845, Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach wrote a comprehensive text on rhinoplasty, titled Operative Chirurgie, and introduced the concept of reoperation to improve the cosmetic appearance of the reconstructed nose.

In 1891, American otorhinolaryngologist John Roe presented an example of his work: a young woman on whom he reduced a dorsal nasal hump for cosmetic indications. In 1892, Robert Weir experimented unsuccessfully with xenografts (duck sternum) in the reconstruction of sunken noses. In 1896, James Israel, a urological surgeon from Germany, and in 1889 George Monks of the United States each described the successful use of heterogeneous free-bone grafting to reconstruct saddle nose defects. In 1898, Jacques Joseph, the German orthopaedic-trained surgeon, published his first account of reduction rhinoplasty. In 1928, Jacques Joseph published Nasenplastik und Sonstige Gesichtsplastik.

Development of modern techniques

The father of modern plastic surgery is generally considered to have been Sir Harold Gillies. A New Zealand otolaryngologist working in London, he developed many of the techniques of modern facial surgery in caring for soldiers suffering from disfiguring facial injuries during the First World War.[16]

During World War I he worked as a medical minder with the Royal Army Medical Corps. After working with the renowned French oral and maxillofacial surgeon Hippolyte Morestin on skin graft, he persuaded the army's chief surgeon, Arbuthnot-Lane, to establish a facial injury ward at the Cambridge Military Hospital, Aldershot, later upgraded to a new hospital for facial repairs at Sidcup in 1917. There Gillies and his colleagues developed many techniques of plastic surgery; more than 11,000 operations were performed on more than 5,000 men (mostly soldiers with facial injuries, usually from gunshot wounds). After the war, Gillies developed a private practice with Rainsford Mowlem, including many famous patients, and travelled extensively to promote his advanced techniques worldwide.

In 1930, Gillies' cousin, Archibald McIndoe, joined the practice and became committed to plastic surgery. When World War II broke out, plastic surgery provision was largely divided between the different services of the armed forces, and Gillies and his team were split up. Gillies himself was sent to Rooksdown House near Basingstoke, which became the principal army plastic surgery unit; Tommy Kilner (who had worked with Gillies during the First World War, and who now has a surgical instrument named after him, the kilner cheek retractor), went to Queen Mary's Hospital, Roehampton, and Mowlem to St Albans. McIndoe, consultant to the RAF, moved to the recently rebuilt Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, Sussex, and founded a Centre for Plastic and Jaw Surgery. There, he treated very deep burn, and serious facial disfigurement, such as loss of eyelids, typical of those caused to aircrew by burning fuel.

McIndoe is often recognized for not only developing new techniques for treating badly burned faces and hands but also for recognising the importance of the rehabilitation of the casualties and particularly of social reintegration back into normal life. He disposed of the "convalescent uniforms" and let the patients use their service uniforms instead. With the help of two friends, Neville and Elaine Blond, he also convinced the locals to support the patients and invite them to their homes. McIndoe kept referring to them as "his boys" and the staff called him "The Boss" or "The Maestro."

His other important work included development of the walking-stalk skin graft, and the discovery that immersion in saline promoted healing as well as improving survival rates for victims with extensive burns — this was a serendipitous discovery drawn from observation of differential healing rates in pilots who had come down on land and in the sea. His radical, experimental treatments led to the formation of the Guinea Pig Club at Queen Victoria Hospital, Sussex. Among the better known members of his "club" were Richard Hillary, Bill Foxley and Jimmy Edwards.

Sub-specialties

Plastic surgery is a broad field, and may be subdivided further. In the United States, plastic surgeons are board certified by American Board of Plastic Surgery.[17] Subdisciplines of plastic surgery may include:

Aesthetic surgery

Aesthetic surgery is a central component of plastic surgery and includes facial and body aesthetic surgery. Plastic surgeons use cosmetic surgical principles in all reconstructive surgical procedures as well as isolated operations to improve overall appearance.[18]

Burn surgery

Burn surgery generally takes place in two phases. Acute burn surgery is the treatment immediately after a burn. Reconstructive burn surgery takes place after the burn wounds have healed.

Craniofacial surgery

Craniofacial surgery is divided into pediatric and adult craniofacial surgery. Pediatric craniofacial surgery mostly revolves around the treatment of congenital anomalies of the craniofacial skeleton and soft tissues, such as cleft lip and palate, craniosynostosis, and pediatric fractures. Adult craniofacial surgery deals mostly with fractures and secondary surgeries (such as orbital reconstruction) along with orthognathic surgery. Craniofacial surgery is an important part of all plastic surgery training programs, further training and subspecialisation is obtained via a craniofacial fellowship. Craniofacial surgery is also practiced by Maxillo-Facial surgeons.

Hand surgery

Hand surgery is concerned with acute injuries and chronic diseases of the hand and wrist, correction of congenital malformations of the upper extremities, and peripheral nerve problems (such as brachial plexus injuries or carpal tunnel syndrome). Hand surgery is an important part of training in plastic surgery, as well as microsurgery, which is necessary to replant an amputated extremity. The hand surgery field is also practiced by orthopedic surgeons and general surgeons. Scar tissue formation after surgery can be problematic on the delicate hand, causing loss of dexterity and digit function if severe enough. There have been cases of surgery to women's hands in order to correct perceived flaws to create the perfect engagement ring photo.[19]

Microsurgery

Microsurgery is generally concerned with the reconstruction of missing tissues by transferring a piece of tissue to the reconstruction site and reconnecting blood vessels. Popular subspecialty areas are breast reconstruction, head and neck reconstruction, hand surgery/replantation, and brachial plexus surgery.

Pediatric plastic surgery

Children often face medical issues very different from the experiences of an adult patient. Many birth defects or syndromes present at birth are best treated in childhood, and pediatric plastic surgeons specialize in treating these conditions in children. Conditions commonly treated by pediatric plastic surgeons include craniofacial anomalies, Syndactyly[20] (webbing of the fingers and toes), Polydactyly (excess fingers and toes at birth), cleft lip and palate, and congenital hand deformities.

Techniques and procedures

In plastic surgery, the transfer of skin tissue (skin grafting) is a very common procedure. Skin grafts can be derived from the recipient or donors:

- Autografts are taken from the recipient. If absent or deficient of natural tissue, alternatives can be cultured sheets of epithelial cells in vitro or synthetic compounds, such as integra, which consists of silicone and bovine tendon collagen with glycosaminoglycans.

- Allografts are taken from a donor of the same species.

- Xenografts are taken from a donor of a different species.

Usually, good results would be expected from plastic surgery that emphasize careful planning of incisions so that they fall within the line of natural skin folds or lines, appropriate choice of wound closure, use of best available suture materials, and early removal of exposed sutures so that the wound is held closed by buried sutures.

Reconstructive surgery

Reconstructive plastic surgery is performed to correct functional impairments caused by burns; traumatic injuries, such as facial bone fractures and breaks; congenital abnormalities, such as cleft palates or cleft lips; developmental abnormalities; infection and disease; and cancer or tumors. Reconstructive plastic surgery is usually performed to improve function, but it may be done to approximate a normal appearance.

The most common reconstructive procedures are tumor removal, laceration repair, maxillofacial surgery, scar revision, hand surgery and breast reduction plasty. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, the number of reconstructive breast reductions for women decreased in 2018 by 4 percent from the year before. Breast reduction in men decreased in 2018 by 8 percent. In 2018, there were 57,535 performed.

Some other common reconstructive surgical procedures include breast reconstruction after a mastectomy for the treatment of cancer, cleft lip and palate surgery, contracture surgery for burn survivors, and creating a new outer ear when one is congenitally absent.

Plastic surgeons use microsurgery to transfer tissue for coverage of a defect when no local tissue is available. Free flaps of skin, muscle, bone, fat, or a combination may be removed from the body, moved to another site on the body, and reconnected to a blood supply by suturing arteries and veins as small as 1 to 2 millimeters in diameter.

Cosmetic surgery procedures

Cosmetic surgery is a voluntary or elective surgery that is performed on normal parts of the body with the only purpose of improving a person’s appearance and/or removing signs of aging. In 2014, nearly 16 million cosmetic procedures were performed in the United States alone.[21] The number of cosmetic procedures performed in the United States has almost doubled since the start of the century. 92% of cosmetic procedures were performed on women in 2014, up from 88% in 2001.[22] Nearly 12 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2007, with the five most common surgeries being breast augmentation, liposuction, breast reduction, eyelid surgery and abdominoplasty. The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery looks at the statistics for 34 different cosmetic procedures. Nineteen of the procedures are surgical, such as rhinoplasty or facelift. The nonsurgical procedures include Botox and laser hair removal. In 2010, their survey revealed that there were 9,336,814 total procedures in the United States. Of those, 1,622,290 procedures were surgical (p. 5). They also found that a large majority, 81%, of the procedures were done on Caucasian people (p. 12).[23]

The American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) estimates that more than 333,000 cosmetic procedures were performed on patients 18 years of age or younger in the US in 2005 compared to approx. 14,000 in 1996. This is significant because it encourages younger people to continue these procedures later in life.[24] The increased use of cosmetic procedures crosses racial and ethnic lines in the U.S., with increases seen among African-Americans, Asian Americans and Hispanic Americans as well as Caucasian Americans. Of 1191 UK newspaper articles, 89% used the term ‘plastic surgery’ in the context of cosmetic surgery. This is significant as it shows the frequency in which the western world portrays cosmetic surgery.[25] In Asia, cosmetic surgery has become more popular, and countries such as China and India have become Asia's biggest cosmetic surgery markets.[26] South Korea is also rising in popularity due to their expertise in facial bone surgeries. The first publication by a team of South Korean surgeons on facial bone contouring surgeries was published illustrating various surgery methods used for facial bone contouring surgeries.[27]

Plastic surgery is increasing slowly, rising 115% from 2000 to 2015. "According to the annual plastic surgery procedural statistics, there were 15.9 million surgical and minimally-invasive cosmetic procedures performed in the United States in 2015, a 2 percent increase over 2014."[28]

The most popular aesthetic/cosmetic procedures include:

- Abdominoplasty ("tummy tuck"): reshaping and firming of the abdomen

- Blepharoplasty ("eyelid surgery"): reshaping of upper/lower eyelids including Asian blepharoplasty

- Phalloplasty ("penile surgery"): construction (or reconstruction) of a penis or, sometimes, artificial modification of the penis by surgery, often for cosmetic purposes

- Mammoplasty:

- Breast augmentations ("breast implant" or "boob job"): augmentation of the breasts by means of fat grafting, saline, or silicone gel prosthetics, which was initially performed for women with micromastia

- Reduction mammoplasty ("breast reduction"): removal of skin and glandular tissue, which is done to reduce back and shoulder pain in women with gigantomastia and for men with gynecomastia

- Mastopexy ("breast lift"): Lifting or reshaping of breasts to make them less saggy, often after weight loss (after a pregnancy, for example). It involves removal of breast skin as opposed to glandular tissue

- Buttock augmentation ("butt implant"): enhancement of the buttocks using silicone implants or fat grafting ("Brazilian butt lift") where fat is transferred from other areas of the body

- Cryolipolysis: refers to a medical device used to destroy fat cells. Its principle relies on controlled cooling for non-invasive local reduction of fat deposits to reshape body contours.

- Cryoneuromodulation: Treatment of superficial and subcutaneous tissue structures using gaseous nitrous oxide, including temporary wrinkle reduction, temporary pain reduction, treatment of dermatologic conditions, and focal cryo-treatment of tissue

- Calf Augmentation: done by silicone implants or fat transfer to add bulk to calf muscles

- Labiaplasty: surgical reduction and reshaping of the labia

- Lip augmentation: alter the appearance of the lips by increasing their fullness through surgical enlargement with lip implants or nonsurgical enhancement with injectable fillers

- Cheiloplasty: surgical reconstruction of the lip

- Rhinoplasty ("nose job"): reshaping of the nose sometimes used to correct breathing impaired by structural defects.

- Otoplasty ("ear surgery"/"ear pinning"): reshaping of the ear, most often done by pinning the protruding ear closer to the head.

- Rhytidectomy ("face lift"): removal of wrinkles and signs of aging from the face

- Neck lift: tightening of lax tissues in the neck. This procedure is often combined with a facelift for lower face rejuvenation.

- Browplasty ("brow lift" or "forehead lift"): elevates eyebrows, smooths forehead skin

- Midface lift ("cheek lift"): tightening of the cheeks

- Genioplasty: augmentation of the chin with an individual's bones or with the use of an implant, usually silicone, by suture of the soft tissue[27]

- Cheek augmentation ("cheek implant"): implants to the cheek

- Orthognathic Surgery: altering the upper and lower jaw bones (through osteotomy) to correct jaw alignment issues and correct the teeth alignment

- Fillers injections: collagen, fat, and other tissue filler injections, such as hyaluronic acid

- Brachioplasty ("Arm lift"): reducing excess skin and fat between the underarm and the elbow

- Laser Skin Rejuvenation or laser resurfacing: the lessening of depth of facial pores and exfoliation of dead or damaged skin cells

- Liposuction ("suction lipectomy"): removal of fat deposits by traditional suction technique or ultrasonic energy to aid fat removal

- Zygoma reduction plasty: reducing the facial width by performing osteotomy and resecting part of the zygomatic bone and arch[27]

- Jaw reduction: reduction of the mandible angle to smooth out an angular jaw and creating a slim jaw[27]

The most popular surgeries are Botox, liposuction, eyelid surgery, breast implants, nose jobs, and facelifts.[29]

Complications, risks and reversals

All surgery has risks. Common complications of cosmetic surgery includes hematoma, nerve damage, infection, scarring, implant failure and organ damage.[30][31][32] Breast implants can have many complications, including rupture. In 2011 FDA stated that one in five patients who received implants for breast augmentation will need them removed within 10 years of implantation.[33]

Psychological disorders

Though media and advertising do play a large role in influencing many people's lives, such as by making people believe plastic surgery to be an acceptable course to change our identities to our liking,[34] researchers believe that plastic surgery obsession is linked to psychological disorders like body dysmorphic disorder. There exists a correlation between sufferers of BDD and the predilection toward cosmetic plastic surgery in order to correct a perceived defect in their appearance.[35]

BDD is a disorder resulting in the sufferer becoming "preoccupied with what they regard as defects in their bodies or faces." Alternatively, where there is a slight physical anomaly, then the person’s concern is markedly excessive.[35] While 2% of people suffer from body dysmorphic disorder in the United States, 15% of patients seeing a dermatologist and cosmetic surgeons have the disorder. Half of the patients with the disorder who have cosmetic surgery performed are not pleased with the aesthetic outcome. BDD can lead to suicide in some of its sufferers. While many with BDD seek cosmetic surgery, the procedures do not treat BDD, and can ultimately worsen the problem. The psychological root of the problem is usually unidentified; therefore causing the treatment to be even more difficult. Some say that the fixation or obsession with correction of the area could be a sub-disorder such as anorexia or muscle dysmorphia.[36] The increased use of body and facial reshaping applications such as Snapchat and Facetune have been identified as a potential triggers of BDD. Recently, a phenomenon referred to as 'Snapchat dysmorphia' has appeared to describe people who request surgery to resemble the edited version of themselves as they appear through Snapchat Filters.[37] As a protest to the detrimental trend, Instagram banned all augmented reality (AR) filters that depict or promote cosmetic surgery.[38]

In some cases, people whose physicians refuse to perform any further surgeries, have turned to "do it yourself" plastic surgery, injecting themselves and running extreme safety risks.[39]

See also

- Biomaterial

- Body modification

- Ethnic plastic surgery

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Scalp reconstruction

- List of plastic surgery flaps

- Cosmetic surgery in Australia

References

- "What is Cosmetic Surgery". Royal College of Surgeons. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. 'plastic'

- "plastic surgery | Britannica.com". OED Online. Britannica. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- "Plastic". Etymonline. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Academy Papyrus to be Exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art". The New York Academy of Medicine. 27 July 2005. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- Shiffman, Melvin (5 September 2012). Cosmetic Surgery: Art and Techniques. Springer. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-642-21837-8.

- Mazzola, Ricardo F.; Mazzola, Isabella C. (5 September 2012). Plastic Surgery: Principles. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-4557-1052-2.

- MSN Encarta (2008). Plastic Surgery Archived 22 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Dwivedi, Girish & Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence. National Informatics Centre (Government of India).

- Lock, Stephen etc. (200ĞďéĠĊ1). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262950-6. (page 607)

- Maniglia, Anthony J (1989). "How I do It". The Laryngoscope. 99 (8): 865–870. doi:10.1288/00005537-198908000-00017. PMID 2666806.

- Lock, Stephen etc. (2001). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262950-6. (page 651)

- Lock, Stephen etc. (2001). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262950-6. (page 652)

- Wolfgang H. Vogel, Andreas Berke (2009). "Brief History of Vision and Ocular Medicine". Kugler Publications. p.97. ISBN 90-6299-220-X

- P. Santoni-Rugiu, A History of Plastic Surgery (2007)

- Chambers, James Alan; Ray, Peter Damian (2009). "Achieving Growth and Excellence in Medicine". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 63 (5): 473–478. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181bc327a. PMID 20431512.

- "Introduction". American Board of Plastic Surgery. 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Description of Plastic Surgery American Board of Plastic Surgery Archived 15 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ABC News. "Hand Rejuvenation for Better Engagement Ring Selfies". ABC News. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Syndactyly at eMedicine

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "2001 Cosmetic Surgery Statistics". Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2010). "Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics". Aesthetic Surgery Journal: 1–18.

- Zuckerman, Diana; Abraham, Anisha (2008). "Teenagers and Cosmetic Surgery: Focus on Breast Augmentation and Liposuction". Journal of Adolescent Health. 43 (4): 318–324. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.018. PMID 18809128.

- Reid, A.J; Malone, P.S.C (2008). "Plastic Surgery in the Press". Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 61 (8): 866–869. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2008.06.012. PMID 18675242.

- India, China Among Plastic Surgery Hot Spots – WebMD

- Park, Sanghoon (2017). Facial bone contouring surgery: a practical guide. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 9789811027260. OCLC 1004601615.

- "New Statistics Reflect the Changing Face of Plastic Surgery". 25 February 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "The Most Popular Cosmetic Procedures". WebMD. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "The 10 Most Common Plastic Surgery Complications".

- Choices, NHS (23 October 2017). "Plastic surgery – Complications – NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk.

- "Cosmetic surgery Risks – Mayo Clinic".

- https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm260235.htm%5B%5D

- Elliott, Anthony (2011). "'I Want to Look Like That!': Cosmetic Surgery and Celebrity Culture". Cultural Sociology. 5 (4): 463–477. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1028.8768. doi:10.1177/1749975510391583.

- Veale, D (2004). "Body dysmorphic disorder". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 80 (940): 67–71. doi:10.1136/pmj.2003.015289. PMC 1742928. PMID 14970291.

- Miller, M. C (2005). "What is body dysmorphic disorder?". The Harvard Mental Health Letter. 22 (1): 8. PMID 16193565.

- MEDICAL CENTER, BOSTON. "A new reality for beauty standards: How selfies and filters affect body image". eurekalert. the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "Instagram bans 'cosmetic surgery' filters". BBC News. 23 October 2019.

- Canning, Andrea (20 July 2009). "Woman's DIY Plastic Surgery 'Nightmare'". ABC News.

Further reading

- Santoni-Rugiu, Paolo (2007). A History of Plastic Surgery. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-46240-8.

- Fraser, Suzanne (2003). Cosmetic surgery, gender and culture. Palgrave. ISBN 978-1-4039-1299-2.

- Gilman, Sander (2005). Creating Beauty to Cure the Soul: Race and Psychology in the Shaping of Aesthetic Surgery. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2144-6.

- Haiken, Elizabeth (1997). Venus Envy: A History of Cosmetic Surgery. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5763-8.

- Atkinson, Michael (2008). "Exploring Male Femininity in the 'Crisis': Men and Cosmetic Surgery". Body & Society. 14: 67–87. doi:10.1177/1357034X07087531.