Obstructed labour

Obstructed labour, also known as labour dystocia, is when the baby does not exit the pelvis during childbirth due to being physically blocked, despite the uterus contracting normally.[2] Complications for the baby include not getting enough oxygen which may result in death.[1] It increases the risk of the mother getting an infection, having uterine rupture, or having post-partum bleeding.[1] Long term complications for the mother include obstetrical fistula.[2] Obstructed labour is said to result in prolonged labour, when the active phase of labour is longer than twelve hours.[2]

| Obstructed labour | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Labour dystocia |

| |

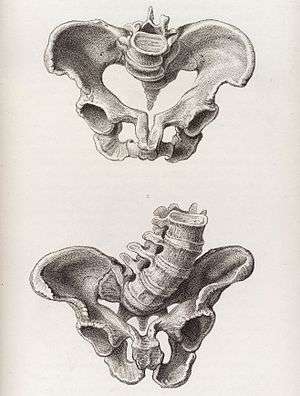

| An image of a deformed pelvis, a risk factor for obstructed labour | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| Complications | Perinatal asphyxia, uterine rupture, post-partum bleeding, postpartum infection[1] |

| Causes | Large or abnormally positioned baby, small pelvis, problems with the birth canal[2] |

| Risk factors | Shoulder dystocia, malnutrition, vitamin D deficiency[3][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Active phase of labour > 12 hours[2] |

| Treatment | Cesarean section, vacuum extraction with possible surgical opening of the symphysis pubis[4] |

| Frequency | 6.5 million (2015)[5] |

| Deaths | 23,100 (2015)[6] |

The main causes of obstructed labour include: a large or abnormally positioned baby, a small pelvis, and problems with the birth canal.[2] Abnormal positioning includes shoulder dystocia where the anterior shoulder does not pass easily below the pubic bone.[2] Risk factors for a small pelvis include malnutrition and a lack of exposure to sunlight causing vitamin D deficiency.[3] It is also more common in adolescence as the pelvis may not have finished growing.[1] Problems with the birth canal include a narrow vagina and perineum which may be due to female genital mutilation or tumors.[2] A partograph is often used to track labour progression and diagnose problems.[1] This combined with physical examination may identify obstructed labour.[7]

The treatment of obstructed labour may require cesarean section or vacuum extraction with possible surgical opening of the symphysis pubis.[4] Other measures include: keeping the women hydrated and antibiotics if the membranes have been ruptured for more than 18 hours.[4] In Africa and Asia obstructed labor affects between two and five percent of deliveries.[8] In 2015 about 6.5 million cases of obstructed labour or uterine rupture occurred.[5] This resulted in 23,000 maternal deaths down from 29,000 deaths in 1990 (about 8% of all deaths related to pregnancy).[2][6][9] It is also one of the leading causes of stillbirth.[10] Most deaths due to this condition occur in the developing world.[1]

Cause

The main causes of obstructed labour include: a large or abnormally positioned baby, a small pelvis, and problems with the birth canal.[2] Both the size and the position of the fetus can lead to obstructed labor. Abnormal positioning includes shoulder dystocia where the anterior shoulder does not pass easily below the pubic bone.[2] A small pelvis of the mother can be a result of many factors. Risk factors for a small pelvis include malnutrition and a lack of exposure to sunlight causing vitamin D deficiency.[3] A deficiency in calcium can also result in a small pelvis as the structures of the pelvic bones will be weak due to the lack of calcium.[11] A relationship between maternal height and pelvis size is present and can be used to predict the possibility of obstructed labor. This relationship is a result of the mother's nutritional health throughout her life leading up to childbirth.[1] Younger mothers are also at more risk for obstructed labor due to growth of the pelvis not being completed.[11] Problems with the birth canal include a narrow vagina and perineum which may be due to female genital mutilation or tumors.[2] All of these mechanical factors lead to a failure to progress in labor.

Evolution

Obstructed labor is unique to humans compared to other primates. The evolution of humans to become obligate bipedal and increase in brain size create the problems associated with obstructed labor.[12] In order for bipedal locomotion to be possible, many changes had to occur to the skeletal structure of humans, especially in the pelvis. Both the shape and orientation of the pelvis changed.[12] Other primates have straighter and wider pelvises compared to humans.[12] A narrow pelvis is better for bipedal locomotion but makes childbirth more difficult. The pelvis is sexually dimorphic, with females having a wider pelvis to be better suited for childbirth. However, the female pelvis still must accommodate for bipedal locomotion which is what creates the challenges for obstructed labor.[12] The brain size of humans has also increased as the species has evolved, resulting in a larger head of the fetus that must exit the womb. This requires human infants to be born less developed when compared to other species. The bones of the skull are not yet fused when a human infant is born in order to prevent the head from becoming too large to exit the womb. However, the head of the fetus is still large and poses the possibility for obstructed labor.[12]

Diagnosis

Obstructed labour is usually diagnosed based on physical examination.[7] Ultrasound can be used to predict malpresentation of the fetus.[11] In examination of the cervix once labor has begun, all examinations are compared to regular cervical assessments. The comparison between the average cervical assessment and the current state of the mother allows for a diagnosis of obstructed labor.[1] An increasingly long time in labor also indicates a mechanical issue that is preventing the fetus from exiting the womb.[1]

Prevention

Access to proper health services can reduce the prevalence of obstructed labor.[11] Less developed areas have inadequate health services to attend to obstructed labor, resulting in a higher prevalence among less developed area. Improving nutrition of female, both before and during pregnancy, is important for reducing the risk of obstructive labor.[11] Creating education programs about reproduction and increasing access to reproductive services such as contraception and family planning in developing areas can also reduce the prevalence of obstructed labor.[13]

Treatment

Before considering surgical options, changing the posture of the mother during labor can help to progress labor.[13] The treatment of obstructed labour may require cesarean section or vacuum extraction with possible surgical opening of the symphysis pubis.[4] Caesarean section is an invasive method but is often the only method that will save the lives of both the mother and the infant.[13] Symphysiotomy is the surgical opening of the symphysis pubis. This procedure can be completed more rapidly than Caesarean sections and does not require anesthesia, making it a more accessible option in places with less advanced medical technology.[13] This procedure also leaves no scars on the uterus which makes further pregnancies and births safer for the mother.[1] Another important factor in treating obstructed labor is monitoring the energy and hydration of the mother.[11] Contractions of the uterus require energy, so the longer the mother is in labor the more energy she expends. When the mother is depleted of energy, the contractions become weaker and labor will become increasingly longer.[1] Antibiotics are also an important treatment as infection is a possible result of obstructed labor.[11]

Prognosis

If cesarean section is obtained in a timely manner, prognosis is good.[1] Prolonged obstructed labour can lead to stillbirth, obstetric fistula, and maternal death.[14] Fetal death can be caused by asphyxia.[1] Obstructed labor is the leading cause of uterine rupture worldwide.[1] Maternal death can result from uterine rupture, complications during caesarean section, or sepsis.[13]

Epidemiology

In 2013 it resulted in 19,000 maternal deaths down from 29,000 deaths in 1990.[9] Globally, obstructed labor accounts for 8% of maternal deaths.[15]

Etymology

The word dystocia means difficult labour.[1] Its antonym is eutocia (Ancient Greek: τόκος, romanized: tókos, lit. 'childbirth') or easy labour.

Other terms for obstructed labour include: difficult labour, abnormal labour, difficult childbirth, abnormal childbirth, and dysfunctional labour.

Other animals

The term can also be used in the context of various animals. Dystocia pertaining to birds and reptiles is also called egg binding.

In part due to extensive selective breeding, miniature horse mares experience dystocias more frequently than other breeds.

Assisted delivery: miniature horse dystocia. Note the position of the head.

Assisted delivery: miniature horse dystocia. Note the position of the head. Miniature horse dystocia. Note the position of the head.

Miniature horse dystocia. Note the position of the head.

References

- Neilson, JP; Lavender, T; Quenby, S; Wray, S (2003). "Obstructed labour". British Medical Bulletin. 67: 191–204. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldg018. PMID 14711764.

- Education material for teachers of midwifery : midwifery education modules (PDF) (2nd ed.). Geneva [Switzerland]: World Health Organisation. 2008. pp. 17–36. ISBN 9789241546669. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-21.

- Education material for teachers of midwifery : midwifery education modules (PDF) (2nd ed.). Geneva [Switzerland]: World Health Organisation. 2008. pp. 38–44. ISBN 9789241546669. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-21.

- Education material for teachers of midwifery : midwifery education modules (PDF) (2nd ed.). Geneva [Switzerland]: World Health Organisation. 2008. pp. 89–104. ISBN 9789241546669. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-21.

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- Education material for teachers of midwifery : midwifery education modules (PDF) (2nd ed.). Geneva [Switzerland]: World Health Organisation. 2008. pp. 45–52. ISBN 9789241546669. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-21.

- Usha, Krishna (2004). Pregnancy at risk : current concepts. New Delhi: Jaypee Bros. p. 451. ISBN 9788171798261. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

|Supplementary Appendix Page 190

- Goldenberg, RL; McClure, EM; Bhutta, ZA; Belizán, JM; Reddy, UM; Rubens, CE; Mabeya, H; Flenady, V; Darmstadt, GL; Lancet's Stillbirths Series steering, committee. (21 May 2011). "Stillbirths: the vision for 2020". Lancet. 377 (9779): 1798–805. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62235-0. PMID 21496912.

- Konje, Justin C; Ladipo, Oladapo A (2000-07-01). "Nutrition and obstructed labor". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 72 (1): 291S–297S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/72.1.291s. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 10871595.

- Wittman, Anna Blackburn; Wall, L Lewis (November 2007). "The Evolutionary Origins of Obstructed Labor: Bipedalism, Encephalization, and the Human Obstetric Dilemma". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 62 (11): 739–748. doi:10.1097/01.ogx.0000286584.04310.5c. ISSN 0029-7828. PMID 17925047.

- Hofmeyr, G.J (2004-05-19). "Obstructed labor: using better technologies to reduce mortality". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 85: S62–S72. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.01.011. ISSN 0020-7292.

- Carmen Dolea, Carla AbouZahr (July 2003). "Global burden of obstructed labour in the year 2000" (PDF). Evidence and Information for Policy (EIP), World Health Organization.

- Khan, Khalid S; Wojdyla, Daniel; Say, Lale; Gülmezoglu, A Metin; Van Look, Paul FA (April 2006). "WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review". The Lancet. 367 (9516): 1066–1074. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68397-9. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 16581405.

Further reading

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Education material for teachers of midwifery : midwifery education modules (PDF) (2nd ed.). Geneva [Switzerland]: World Health Organisation. 2008. ISBN 9789241546669.