Assisted reproductive technology

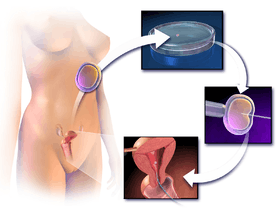

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) includes medical procedures used primarily to address infertility. This subject involves procedures such as in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), cryopreservation of gametes or embryos, and/or the use of fertility medication. When used to address infertility, ART may also be referred to as fertility treatment. ART mainly belongs to the field of reproductive endocrinology and infertility. Some forms of ART may be used with regard to fertile couples for genetic purpose (see preimplantation genetic diagnosis). ART may also be used in surrogacy arrangements, although not all surrogacy arrangements involve ART.

| Assisted reproductive technology | |

|---|---|

Illustration depicting intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), an example of assisted reproductive technology. | |

| MeSH | D027724 |

Procedures

General

With ART, the process of sexual intercourse is bypassed and fertilization of the oocytes occurs in the laboratory environment (i.e., in vitro fertilization).

In the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—which —defines ART to include "all fertility treatments in which both eggs and sperm are handled. In general, ART procedures involve surgically removing eggs from a woman's ovaries, combining them with sperm in the laboratory, and returning them to the woman's body or donating them to another woman." According to CDC, "they do not include treatments in which only sperm are handled (i.e., intrauterine—or artificial—insemination) or procedures in which a woman takes medicine only to stimulate egg production without the intention of having eggs retrieved."[1]

In Europe, ART also excludes artificial insemination and includes only procedures where oocytes are handled.[2][3]

The WHO, or World Health Organization, also defines ART this way.[4]

Ovulation induction

Ovulation induction is usually used in the sense of stimulation of the development of ovarian follicles[5][6][7] by fertility medication to reverse anovulation or oligoovulation.

In vitro fertilization

In vitro fertilization is the technique of letting fertilization of the male and female gametes (sperm and egg) occur outside the female body.

Techniques usually used in in vitro fertilization include:

- Transvaginal ovum retrieval (OVR) is the process whereby a small needle is inserted through the back of the vagina and guided via ultrasound into the ovarian follicles to collect the fluid that contains the eggs.

- Embryo transfer is the step in the process whereby one or several embryos are placed into the uterus of the female with the intent to establish a pregnancy.

Less commonly used techniques in in vitro fertilization are:

- Assisted zona hatching (AZH) is performed shortly before the embryo is transferred to the uterus. A small opening is made in the outer layer surrounding the egg in order to help the embryo hatch out and aid in the implantation process of the growing embryo.

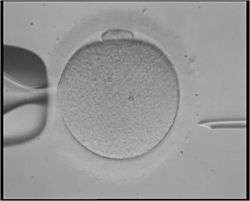

- Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) is beneficial in the case of male factor infertility where sperm counts are very low or failed fertilization occurred with previous IVF attempt(s). The ICSI procedure involves a single sperm carefully injected into the center of an egg using a microneedle. With ICSI, only one sperm per egg is needed. Without ICSI, you need between 50,000 and 100,000. This method is also sometimes employed when donor sperm is used.

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) - Autologous endometrial coculture is a possible treatment for patients who have failed previous IVF attempts or who have poor embryo quality. The patient's fertilized eggs are placed on top of a layer of cells from the patient's own uterine lining, creating a more natural environment for embryo development.

- In zygote intrafallopian transfer (ZIFT), egg cells are removed from the woman's ovaries and fertilized in the laboratory; the resulting zygote is then placed into the fallopian tube.

- Cytoplasmic transfer is the technique in which the contents of a fertile egg from a donor are injected into the infertile egg of the patient along with the sperm.

- Egg donors are resources for women with no eggs due to surgery, chemotherapy, or genetic causes; or with poor egg quality, previously unsuccessful IVF cycles or advanced maternal age. In the egg donor process, eggs are retrieved from a donor's ovaries, fertilized in the laboratory with the sperm from the recipient's partner, and the resulting healthy embryos are returned to the recipient's uterus.

- Sperm donation may provide the source for the sperm used in IVF procedures where the male partner produces no sperm or has an inheritable disease, or where the woman being treated has no male partner.

- Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) involves the use of genetic screening mechanisms such as fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) or comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) to help identify genetically abnormal embryos and improve healthy outcomes.

- Embryo splitting can be used for twinning to increase the number of available embryos.[8]

Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis

A pre-implantation genetic diagnosis procedure may be conducted on embryos prior to implantation (as a form of embryo profiling), and sometimes even of oocytes prior to fertilization. PGD is considered in a similar fashion to prenatal diagnosis. PGD is an adjunct to ART procedures, and requires in vitro fertilization to obtain oocytes or embryos for evaluation. Embryos are generally obtained through blastomere or blastocyst biopsy. The latter technique has proved to be less deleterious for the embryo, therefore it is advisable to perform the biopsy around day 5 or 6 of development.[9] Sex selection is the attempt to control the sex of offspring to achieve a desired sex. It can be accomplished in several ways, both pre- and post-implantation of an embryo, as well as at birth. Pre-implantation techniques include PGD, but also sperm sorting.

Others

Other assisted reproduction techniques include:

- Mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT, sometimes called mitochondrial donation) is the replacement of mitochondria in one or more cells to prevent or ameliorate disease. MRT originated as a special form of IVF in which some or all of the future baby's mitochondrial DNA comes from a third party. This technique is used in cases when mothers carry genes for mitochondrial diseases. The therapy is approved for use in the United Kingdom.[10][11]

- In gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT) a mixture of sperm and eggs is placed directly into a woman's fallopian tubes using laparoscopy following a transvaginal ovum retrieval.

- Reproductive surgery, treating e.g. fallopian tube obstruction and vas deferens obstruction, or reversing a vasectomy by a reverse vasectomy. In surgical sperm retrieval (SSR) the reproductive urologist obtains sperm from the vas deferens, epididymis or directly from the testis in a short outpatient procedure.

- By cryopreservation, eggs, sperm and reproductive tissue can be preserved for later IVF.

Risks

The majority of IVF-conceived infants do not have birth defects.[12] However, some studies have suggested that assisted reproductive technology is associated with an increased risk of birth defects.[13][14] Artificial reproductive technology is becoming more available. Early studies suggest that there could be an increased risk for medical complications with both the mother and baby. Some of these include low birth weight, placental insufficiency, chromosomal disorders, preterm deliveries, gestational diabetes, and pre-eclampsia (Aiken and Brockelsby).[15]

In the largest U.S. study, which used data from a statewide registry of birth defects,[16] 6.2% of IVF-conceived children had major defects, as compared with 4.4% of naturally conceived children matched for maternal age and other factors (odds ratio, 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.00 to 1.67).[12] ART carries with it a risk for heterotopic pregnancy (simultaneous intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancy).[17] The main risks are:

- Genetic disorders

- Low birth weight.[18] In IVF and ICSI, a risk factor is the decreased expression of proteins in energy metabolism; Ferritin light chain and ATP5A1.[19]

- Preterm birth. Low birth weight and preterm birth are strongly associated with many health problems, such as visual impairment and cerebral palsy. Children born after IVF are roughly twice as likely to have cerebral palsy.[20]

Sperm donation is an exception, with a birth defect rate of almost a fifth compared to the general population. It may be explained by that sperm banks accept only people with high sperm count.

Current data indicate little or no increased risk for postpartum depression among women who use ART.[21]

Usage of assisted reproductive technology including ovarian stimulation and in vitro fertilization have been associated with an increased overall risk of childhood cancer in the offspring, which may be caused by the same original disease or condition that caused the infertility or subfertility in the mother or father.[22]

That said, In a landmark paper by Jacques Balayla et al. it was determined that infants born after ART have similar neurodevelopment than infants born after natural conception.[23]

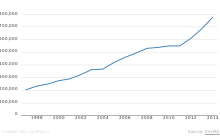

Usage

As a result of the 1992 Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act, the CDC is required to publish the annual ART success rates at U.S. fertility clinics[24]. Assisted reproductive technology procedures performed in the U.S. has over than doubled over the last 10 years, with 140,000 procedures in 2006,[25] resulting in 55,000 births.[25]

In Australia, 3.1% of births are a result of ART.[26]

The most common reasons for discontinuation of fertility treatment have been estimated to be: postponement of treatment (39%), physical and psychological burden (19%, psychological burden 14%, physical burden 6.32%), relational and personal problems (17%, personal reasons 9%, relational problems 9%), treatment rejection (13%) and organizational (12%) and clinic (8%) problems.[27]

By country

United States

Many Americans do not have insurance coverage for fertility investigations and treatments. Many states are starting to mandate coverage, and the rate of use is 278% higher in states with complete coverage.[28]

There are some health insurance companies that cover diagnosis of infertility, but frequently once diagnosed will not cover any treatment costs.

Approximate treatment/diagnosis costs in the United States, with inflation, as of 2018 (US$):

- Initial workup: hysteroscopy, hysterosalpingogram, blood tests ~$2,600

- Sonohysterogram (SHG) ~ $770–$1,300

- Clomiphene citrate cycle ~ $260–$640

- IVF cycle ~ $12,800–$38,500

- Use of a surrogate mother to carry the child – dependent on arrangements

Another way to look at costs is to determine the expected cost of establishing a pregnancy. Thus, if a clomiphene treatment has a chance to establish a pregnancy in 8% of cycles and costs $640, the expected cost is $7,700 to establish a pregnancy, compared to an IVF cycle (cycle fecundity 40%) with a corresponding expected cost of $38,500 ($15,400 × 40%).

For the community as a whole, the cost of IVF on average pays back by 700% by tax from future employment by the conceived human being.[29]

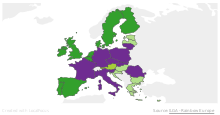

European Union

In Europe, 157,500 children were born using assisted reproductive technology in 2015, according to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE).[30] But there are major differences in legislation across the Old Continent. A European directive fixes standards concerning the use of human tissue and cells,[32] but all ethical and legal questions on ART remain the prerogative of EU member states.

Across Europe, the legal criteria per availability vary somewhat.[34] In 10 countries all women may benefit; in 10 others only heterosexual couples are concerned; in 7 only single women; and in 1 (Austria) only lesbian couples. Spain was the first European country to open ART to all women, in 1977, the year the first sperm bank was opened there. In France, the right to ART is only accorded to heterosexual couples who can justify medical infertility or serious illness. In the last 15 years, legislation has evolved quickly. For example, Portugal made ART available in 2006 with conditions very similar to those in France, before amending the law in 2016 to allow lesbian couples and single women to benefit. Italy clarified its uncertain legal situation in 2004 by adopting Europe’s strictest laws: ART is only available to heterosexual couples, married or otherwise, and sperm donation is prohibited.

Today, 21 countries provide partial public funding for ART treatment. The seven others, which do not, are Ireland, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, and Romania. Such subsidies are subject to conditions, however. In Belgium, a fixed payment of €1,073 is made for each full cycle of the IVF process. The woman must be aged under 43 and may not carry out more than six cycles of ART. There is also a limit on the number of transferable embryos, which varies according to age and the number of cycles completed. In France, ART is subsidized in full by national health insurance for women up to age 43, with limits of 4 attempts at IVF and 6 at artificial insemination. Germany tightened its conditions for public funding in 2004, which caused a sharp drop in the number of ART cycles carried out, from more than 102,000 in 2003 to fewer than 57,000 the following year. Since then the figure has remained stable.

17 countries limit access to ART according to the age of the woman. 10 countries have established an upper age limit, varying from 40 (Finland, Netherlands) to 50 (including Spain, Greece and Estonia). Since 1994, France is one of a number of countries (including Germany, Spain, and the UK) which use the somewhat vague notion of “natural age of procreation”. In 2017, the steering council of France’s Agency of Biomedicine established an age limit of 43 for women using ART. 10 countries have no age limit for ART. These include Austria, Hungary, Italy and Poland.

Most European countries allow donations of gametes by third parties. But the situations vary depending on whether sperm or eggs are concerned. Sperm donations are authorized in 20 EU member states; in 11 of them anonymity is allowed. Egg donations are possible in 17 states, including 8 under anonymous conditions. On 12 April, the Council of Europe adopted a recommendation which encourages an end to anonymity.[35] In the UK, anonymous sperm donations ended in 2005 and children have access to the identity of the donor when they reach adulthood. In France, the principle of anonymous donations of sperm or embryos is maintained in the law of bioethics of 2011, but a new bill under discussion may change the situation.[36]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, all patients have the right to preliminary testing, provided free of charge by the National Health Service (NHS). However, treatment is not widely available on the NHS and there can be long waiting lists. Many patients therefore pay for immediate treatment within the NHS or seek help from private clinics.

In 2013, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published new guidelines about who should have access to IVF treatment on the NHS in England and Wales.[37]

The guidelines say women aged between 40 and 42 should be offered one cycle of IVF on the NHS if they have never had IVF treatment before, have no evidence of low ovarian reserve (this is when eggs in the ovary are low in number, or low in quality), and have been informed of the additional implications of IVF and pregnancy at this age. However, if tests show IVF is the only treatment likely to help them get pregnant, women should be referred for IVF straight away.

This policy is often modified by local Clinical Commissioning Groups, in a fairly blatant breach of the NHS Constitution for England which provides that patients have the right to drugs and treatments that have been recommended by NICE for use in the NHS. For example, the Cheshire, Merseyside and West Lancashire Clinical Commissioning Group insists on additional conditions:[38]

- The person undergoing treatment must have commenced treatment before her 40th birthday;

- The person undergoing treatment must have a BMI of between 19 and 29;

- Neither partner must have any living children, from either the current or previous relationships. This includes adopted as well as biological children; and,

- Sub-fertility must not be the direct result of a sterilisation procedure in either partner (this does not include conditions where sterilisation occurs as a result of another medical problem). Couples who have undertaken a reversal of their sterilisation procedure are not eligible for treatment.

Canada

Some treatments are covered by OHIP (public health insurance) in Ontario and others are not. Women with bilaterally blocked fallopian tubes and are under the age of 40 have treatment covered but are still required to pay test fees (around CA$3,000–4,000). Coverage varies in other provinces. Most other patients are required to pay for treatments themselves.[39]

Israel

Israel's national health insurance, which is mandatory for all Israeli citizens, covers nearly all fertility treatments. IVF costs are fully subsidized up to the birth of two children for all Israeli women, including single women and lesbian couples. Embryo transfers for purposes of gestational surrogacy are also covered.[40]

Germany

On 27 January 2009, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that it is unconstitutional, that the health insurance companies have to bear only 50% of the cost for IVF.[41] On 2 March 2012, the Federal Council has approved a draft law of some federal states, which provides that the federal government provides a subsidy of 25% to the cost. Thus, the share of costs borne for the pair would drop to just 25%.[42]

Society and culture

Ethics

Some couples may find it difficult to stop treatment despite very bad prognosis, resulting in futile therapies. This has the potential to give ART providers a difficult decision of whether to continue or refuse treatment.[43]

Some assisted reproductive technologies have the potential to be harmful to both the mother and child, posing a psychological and/or physical health risk, which may impact the ongoing use of these treatments.

Fictional representation

Films and other fiction depicting emotional struggles of assisted reproductive technology have had an upswing in the latter part of the 2000s decade, although the techniques have been available for decades.[44] As ART becomes more utilized, the number of people that can relate to it by personal experience in one way or another is growing.[44]

For specific examples, refer to the fiction sections in individual subarticles, e.g. surrogacy, sperm donation and fertility clinic.

In addition, reproduction and pregnancy in speculative fiction has been present for many decades.

Research and speculative uses

The idea of using future ART techniques, including direct human germline engineering technologies, to select and genetically modify embryos for the purpose of human enhancement has been referred to as designer babies, reprogenetics, and liberal eugenics and has been discussed since the introduction of biotechnology in the late 1970s.[45][46][47][48][49][50]

The term "liberal eugenics" was coined by bioethicist Nicholas Agar.[51][52] Liberal eugenics is aimed at "improving" the genotypes of future generations through screening and genetic modification to eliminate "undesirable" traits. The term "reprogenetics" was coined by Lee M. Silver, a professor of molecular biology at Princeton University, in his 1997 book Remaking Eden.[53][54]

The philosophical movement associated with these speculative uses is transhumanism.[55][56] When eugenics is discussed in this context it usually in context of allowing parents to select desirable traits in an unborn child and not in the use of genetics to destroy embryos or to prevent the formation of undesirable embryos.

This procedure does not have to encompass liberal eugenics in terms of human enhancement though. It could be an option for both women and men unable to conceive a child naturally, as well as same-sex couples.[57]

Safety is a major concern when it comes to the gene editing and mitochondrial transfer, as problems may not arise in the first children for many years, and their offspring may be affected, and problems may only appear in those subsequent generations.[58][59][60] New diseases may be introduced accidentally.[61][62]

Neither the first generation nor their offspring will have given consent to have been treated.[59] On a larger scale, germline modification has the potential to impact the gene pool of the entire human race in a negative or positive way.[63]

Another concern, especially for people who believe that life begins at conception, is the fate of flawed or unchosen embryos created during the work of reaching an embryo with the desired qualities.[59] The embryo cannot give consent and some of the treatments have long-lasting and harmful implications.[59]

In many countries, editing embryos and germline modification is illegal.[64] As of 2015, 15 of 22 Western European nations had outlawed human germline engineering.[65] Human germline modification has for many years has been heavily off limits. As of 2016 there was no legislation in the United States that explicitly prohibited germline engineering, however, the Consolidated Appropriation Act of 2016 banned the use of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) funds to engage in research regarding human germline modifications.[66]

Germline modification is considered a more ethically and morally acceptable treatment when one or both of the parents is a carrier for a harmful trait and is treated to improve the genotype and safety of the future generations.[59] When the treatment is used for this purpose, it can fill the gaps that other technologies may not be able to accomplish.[63] The American National Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Medicine gave qualified support to human genome editing in 2017 once answers have been found to safety and efficiency problems "but only for serious conditions under stringent oversight."[67] Germline modification would be more practical if sampling methods were less destructive and used the polar bodies rather than embryos.[59] In 2018, the Nuffield Council on Bioethics issued a report which concluded that under certain circumstances, editing of the DNA of human embryos could be acceptable.[68] The Nuffield Council is a British independent organisation that evaluates ethical questions in medicine and biology.

Lee Silver has projected a dystopia in which a race of superior humans look down on those without genetic enhancements, though others have counseled against accepting this vision of the future.[53] It has also been suggested that if designer babies were created through genetic engineering, that this could have deleterious effects on the human gene pool.[69] Some futurists claim that it would put the human species on a path to participant evolution.[53][70] It has also been argued that designer babies may have an important role as counter-acting an argued dysgenic trend.[71]

In November 2018, Jiankui He announced that he had edited the genomes of two human embryos, to attempt to disable the gene for CCR5, which codes for a receptor that HIV uses to enter cells. He said that twin girls, Lulu and Nana, had been born a few weeks earlier. He said that the girls still carried functional copies of CCR5 along with disabled CCR5 (mosaicism) and were still vulnerable to HIV. The work was widely condemned as unethical, dangerous, and premature.[72] Carl Zimmer compared the reaction to He's human gene editing experiment to the initial reactions and subsequent debate over mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT) and the eventual regulatory approval of MRT in the United Kingdom.[73]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Assisted reproductive technology. |

- Artificial uterus

- Diethylstilbestrol

- Human cloning

- Religious response to ART

- Sperm bank

- Sperm donation

- Spontaneous conception, the unassisted conception of a subsequent child after prior use of assisted reproductive technology

- Egg donation

References

![]()

- "What is Assisted Reproductive Technology? | Reproductive Health | CDC". CDC. November 14, 2014. Archived from the original on November 1, 2017.

- European IVF-Monitoring Consortium (EIM) for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; et al. (August 2016). "Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2012: results generated from European registers by ESHRE". Human Reproduction (Oxford, England). 31 (8): 1638–52. doi:10.1093/humrep/dew151. PMID 27496943.

- Sorenson, Corinna (Autumn 2006). "ART in the European Union" (PDF). Euro Observer Euro Observer. 8 (4). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-29.

- Zegers-Hochschild, F; for the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology and the World Health Organization; et al. (November 2009). "International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009" (PDF). Fertility and Sterility. 92 (5): 1520–4. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.009. PMID 19828144. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-29.

- Ovulation Problems and Infertility: Treatment of ovulation problems with Clomid and other fertility drugs. Advanced Fertility Center of Chicago. Gurnee & Crystal Lake, Illinois. Retrieved on Mars 7, 2010

- Flinders reproductive medicine > Ovulation Induction Archived 2009-10-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on Mars 7, 2010

- fertilityLifeLines > Ovulation Induction Archived 2013-03-10 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on Mars 7, 2010

- Illmensee K, Levanduski M, Vidali A, Husami N, Goudas VT (February 2009). "Human embryo twinning with applications in reproductive medicine". Fertil. Steril. 93 (2): 423–7. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.098. PMID 19217091.

- Sullivan-Pyke, C; Dokras, A (March 2018). "Preimplantation Genetic Screening and Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 45 (1): 113–125. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2017.10.009. PMID 29428279.

- Committee on the Ethical and Social Policy Considerations of Novel Techniques for Prevention of Maternal Transmission of Mitochondrial DNA Diseases; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine (2016). Claiborne, Anne; English, Rebecca; Kahn, Jeffrey (eds.). Mitochondrial Replacement Techniques: Ethical, Social, and Policy Considerations. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-38870-2. Index page with links to summaries including one page summary flyer.

- Cree, L; Loi, P (January 2015). "Mitochondrial replacement: from basic research to assisted reproductive technology portfolio tool-technicalities and possible risks". Molecular Human Reproduction. 21 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1093/molehr/gau082. PMID 25425606.

- Van Voorhis BJ (2007). "Clinical practice. In vitro fertilization". N Engl J Med. 356 (4): 379–86. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp065743. PMID 17251534.

- Kurinczuk JJ, Hansen M, Bower C (2004). "The risk of birth defects in children born after assisted reproductive technologies". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 16 (3): 201–9. doi:10.1097/00001703-200406000-00002. PMID 15129049.

- Hansen M, Bower C, Milne E, de Klerk N, Kurinczuk JJ (2005). "Assisted reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects—a systematic review". Hum Reprod. 20 (2): 328–38. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh593. PMID 15567881.

- Aiken, Catherine E. M.; Brockelsby, Jeremy C. (2016). "Fetal and Maternal Consequences of Pregnancies Conceived Using Art". Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review. 25 (3–4): 281–294. doi:10.1017/S096553951600005X.

- Olson CK, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Romitti PA, Budelier WT, Ryan G, Sparks AE, Van Voorhis BJ (2005). "In vitro fertilization is associated with an increase in major birth defects". Fertil Steril. 84 (5): 1308–15. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.086. PMID 16275219.

- MD, Daniel M. Avery, MD, Marion D. Reed, MD, William L. Lenahan. "What you should know about heterotopic pregnancy : OBG Management". www.obgmanagement.com. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- "In vitro fertilization (IVF): MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Zhang Y, Zhang YL, Feng C, et al. (September 2008). "Comparative proteomic analysis of human placenta derived from assisted reproductive technology". Proteomics. 8 (20): 4344–56. doi:10.1002/pmic.200800294. PMID 18792929.

- Hvidtjørn D, Schieve L, Schendel D, Jacobsson B, Sværke C, Thorsen P (2009). "Cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorders, and developmental delay in children born after assisted conception: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 163 (1): 72–83. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.507. PMID 19124707.

- Ross, L. E.; McQueen, K.; Vigod, S.; Dennis, C.-L. (2010). "Risk for postpartum depression associated with assisted reproductive technologies and multiple births: A systematic review". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (1): 96–106. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq025. PMID 20605900.

- Hargreave, Marie; Jensen, Allan; Toender, Anita; Andersen, Klaus Kaae; Kjaer, Susanne Krüger (2013). "Fertility treatment and childhood cancer risk: A systematic meta-analysis". Fertility and Sterility. 100 (1): 150–61. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.03.017. PMID 23562045.

- Balayla, Jacques, Odile Sheehy, William D. Fraser, Jean R. Séguin, Jacquetta Trasler, Patricia Monnier, Andrea A. MacLeod, Marie-Noëlle Simard, Gina Muckle, and Anick Bérard. "Neurodevelopmental Outcomes After Assisted Reproductive Technologies." Obstetrics & Gynecology (2017).

- "Policy Document | Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) | Reproductive Health | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-01-31. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- chicagotribune.com Infertility by the numbers Archived 2009-07-05 at the Wayback Machine Colleen Mastony. June 21, 2009

- 'More IVF babies but less multiple births' Archived 2009-09-24 at the Wayback Machine THE AUSTRALIAN. September 24, 2009

- Gameiro, S.; Boivin, J.; Peronace, L.; Verhaak, C. M. (2012). "Why do patients discontinue fertility treatment? A systematic review of reasons and predictors of discontinuation in fertility treatment". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (6): 652–69. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms031. PMC 3461967. PMID 22869759.

- Jain T, Harlow BL, Hornstein MD (August 2002). "Insurance coverage and outcomes of in vitro fertilization". N. Engl. J. Med. 347 (9): 661–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa013491. PMID 12200554.

- Connolly MP, Pollard MS, Hoorens S, Kaplan BR, Oskowitz SP, Silber SJ (September 2008). "Long-term economic benefits attributed to IVF-conceived children: a lifetime tax calculation". Am J Manag Care. 14 (9): 598–604. PMID 18778175.

- Jézéquélou, Orlane (23 October 2019). "How does assisted reproductive technology work in Europe?". Alternatives Economiques/EDJNet. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- De Geyter, Ch.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; Kupka, M.S.; Wyns, C.; Mocanu, E.; Motrenko, T.; Scaravelli, G.; Smeenk, J.; Vidakovic1, S.; Goossens, V. (September 2018). "ART in Europe, 2014: results generated from European registries by ESHRE: The European IVF-monitoring Consortium (EIM) for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE)". Human Reproduction. 33 (9): 1586–1601. doi:10.1093/humrep/dey242. PMID 30032255.

- "Directive 2004/23/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 on setting standards of quality and safety for the donation, procurement, testing, processing, preservation, storage and distribution of human tissues and cells". Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "Rainbow Map". ILGA-Europe. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "Encadrement juridique international dans les différents domaines de la bioéthique" (PDF) (in French). Agence de la biomédecine. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- "Recommendation 2156 (2019) - Anonymous donation of sperm and oocytes: balancing the rights of parents, donors and children". Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- Céline Mouzon (2019-09-23). "PMA: panique dans la filiation" (in French). Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- "IVF". NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "Services & how we can help". Liverpool Women's NHS Foundation Trust. Archived from the original on 2014-06-24. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "IVF Canada". Archived from the original on August 8, 2009.

- Teman, Elly. 2010. Birthing a Mother: the Surrogate Body and the Pregnant Self. Archived 2009-11-21 at the Wayback Machine Berkeley: University of California Press

- Zuschüsse der Krankenversicherung für eine künstliche Befruchtung Archived 2013-02-08 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2. January 2013.

- Finanzierung künstlicher Befruchtung Archived 2013-02-19 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2. January 2013.

- Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2009). "Fertility treatment when the prognosis is very poor or futile". Fertility and Sterility. 92 (4): 1194–7. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.979. PMID 19726040.

- chicagotribune.com --> Heartache of infertility shared on stage, screen Archived 2012-07-03 at Archive.today By Colleen Mastony, Tribune reporter. June 21, 2009

- Gordon JW (1999). "Genetic enhancement in humans". Science. 283 (5410): 2023–4. Bibcode:1999Sci...283.2023G. doi:10.1126/science.283.5410.2023. PMID 10206908.

- Pray, L. (2008) Embryo screening and the ethics of human genetic engineering. Nature Education 1(1):207 (Retrieved January 24, 2015).

- Erik Parens and Lori P. Knowles (2003). "Reprogenetics and Public Policy Reflections and Recommendations" (PDF). Hastings Center. Retrieved January 24, 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ishii, Tetsuya (August 2014). "Potential impact of human mitochondrial replacement on global policy regarding germline gene modification". Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 29 (2): 150–155. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.04.001. hdl:2115/56864. ISSN 1472-6491. PMID 24832374.

- Cole-Turner, Ronald (2008). Design and Destiny: Jewish and Christian Perspectives on Human Germline Modification. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-53301-0.

- Stock, Gregory (2003). Redesigning Humans: Choosing Our Genes, Changing Our Future. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-34083-5.

- Agar, Nicholas (2004). Liberal Eugenics: In Defence of Human Enhancement. ISBN 978-1-4051-2390-7.

- "Regulating Eugenics". Harvard Law Review. 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- Silver, Lee M. (1998). Remaking Eden: Cloning and Beyond in a Brave New World. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-380-79243-6.

- Kistler, Walter P. (2001). "Genetics in the New Millennium: The Promise of Reprogenics". Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2007-11-13. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wagner, Cynthia G. (2002). "Germinal Choice Technology: Our Evolutionary Future. An Interview with Gregory Stock". Archived from the original on 2006-02-07. Retrieved 2006-02-21. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Black, Edwin (2003). War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race. Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 978-1-56858-258-0.

- Falloon, Katie (2014-01-01). "ART and the Art of Medicine". AMA Journal of Ethics. 16 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.1.fred1-1401. ISSN 2376-6980.

- Anderson, W. French (1985-08-01). "Human Gene Therapy: Scientific and Ethical Considerations". Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. 10 (3): 275–292. doi:10.1093/jmp/10.3.275. ISSN 0360-5310. PMID 3900264.

- Lappé, Marc (1991-12-01). "Ethical Issues in Manipulating the Human Germ Line". Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. 16 (6): 621–639. doi:10.1093/jmp/16.6.621. ISSN 0360-5310. PMID 1787391.

- Pang, Ronald T.K (January 2016). "Designer babies". Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine. 26 (2): 59–60. doi:10.1016/j.ogrm.2015.11.011. hdl:10722/234869.

- Green, Ronald M. (2007). Babies By Design: The Ethics of Genetic Choice. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-300-12546-7. 129954761.

- Agar, Nicholas (2006). "Designer Babies: Ethical Considerations". ActionBioscience.org.

- Smith, Kevin R.; Chan, Sarah; Harris, John (2012). "Human Germline Genetic Modification: Scientific and Bioethical Perspectives". Archives of Medical Research. 43 (7): 491–513. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.09.003. PMID 23072719.

- Ishii, T (August 2015). "Germline genome-editing research and its socioethical implications". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 21 (8): 473–81. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2015.05.006. PMID 26078206.

- Lanphier, Edward; Urnov, Fyodor; Haecker, Sarah Ehlen; Werner, Michael; Smolenski, Joanna (2015-03-26). "Don't edit the human germ line". Nature. 519 (7544): 410–411. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..410L. doi:10.1038/519410a. PMID 25810189.

- Cohen, I. Glenn; Adashi, Eli Y. (2016-08-05). "The FDA is prohibited from going germline". Science. 353 (6299): 545–546. Bibcode:2016Sci...353..545C. doi:10.1126/science.aag2960. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27493171.

- Harmon, Amy (2017-02-14). "Human Gene Editing Receives Science Panel's Support". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-17.

- Hawkes, Nigel (2018-07-17). "Human genome editing is not unethical, says Nuffield Council". BMJ. 362: k3140. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3140. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 30018086.

- Baird, Stephen L. (April 2007). "Designer Babies: Eugenics Repackaged or Consumer Options?" (PDF). Technology Teacher. 66 (7): 12–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 28, 2014.

- Hughes, James (2004). Citizen Cyborg: Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-4198-9.

- Lynn, Richard; Harvey, John (2008). "The decline of the world's IQ". Intelligence. 36 (2): 112–20. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.03.004.

- Begley, Sharon (28 November 2018). "Amid uproar, Chinese scientist defends creating gene-edited babies – STAT". STAT.

- Zimmer, Carl (1 December 2018). "Genetically Modified People Are Walking Among Us". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

Further reading

- Hauskeller, Michael. Philosophical Review of Nicholas Agar's Liberal Eugenics: In Defence of Human Enhancement. Retrieved on 2008-08-03.

- Hari, Johann. Why I support liberal eugenics. Retrieved on 2008-08-03

- Kanamori, Osamu. Relief and Shadow of New Liberal Eugenics. Retrieved on 2008-08-03

- David, Pearce "Liberal Eugenics?". Retrieved on 2010-6-27