Dysentery

Dysentery is a type of gastroenteritis that results in diarrhea with blood.[1][7] Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation.[2][8][5] Complications may include dehydration.[3]

| Dysentery | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bloody diarrhea |

| |

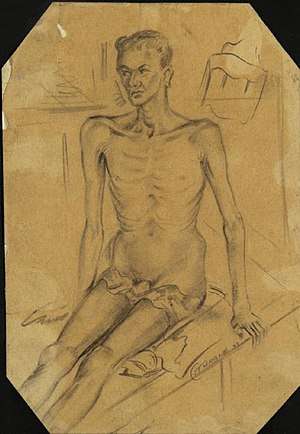

| A person with dysentery in a Burmese hospital, 1943 | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever[1][2] |

| Complications | Dehydration[3] |

| Duration | Less than a week[4] |

| Causes | Usually Shigella or Entamoeba histolytica[1] |

| Risk factors | Contamination of food and water with feces due to poor sanitation[5] |

| Prevention | Hand washing, food safety[4] |

| Treatment | Drinking sufficient fluids, antibiotics (severe cases)[4] |

| Frequency | Common in the developing world[6] |

| Deaths | > million a year[6] |

The cause is usually Shigella, in which case it is known as shigellosis, or Entamoeba histolytica.[1] Other causes may include certain chemicals, other bacteria, other protozoa, or parasitic worms.[2] It may spread between people.[4] Risk factors include contamination of food and water with feces due to poor sanitation.[5] The underlying mechanism involves inflammation of the intestine, especially of the colon.[2]

Efforts to prevent dysentery include hand washing and food safety measures while traveling in areas of high risk.[4] While the condition generally resolves on its own within a week, drinking sufficient fluids such as oral rehydration solution is important.[4] Antibiotics such as azithromycin may be used to treat cases associated with travelling in the developing world.[8] While medications used to decrease diarrhea such as loperamide are not recommended on their own, they may be used together with antibiotics.[8][4]

Shigella results in about 165 million cases of diarrhea and 1.1 million deaths a year with nearly all cases in the developing world.[6] In areas with poor sanitation nearly half of cases of diarrhea are due to Entamoeba histolytica.[5] Entamoeba histolytica affects millions of people and results in greater than 55,000 deaths a year.[9] It commonly occurs in less developed areas of Central and South America, Africa, and Asia.[9] Dysentery has been described at least since the time of Hippocrates.[10]

Signs and symptoms

The most common form of dysentery is bacillary dysentery, which is typically a mild sickness, causing symptoms normally consisting of mild gut pains and frequent passage of stool or diarrhea. Symptoms normally present themselves after 1–3 days, and are usually no longer present after a week. The frequency of urges to defecate, the large volume of liquid feces ejected, and the presence of blood, mucus, or pus depends on the pathogen causing the disease. Temporary lactose intolerance can occur, as well. In some caustic occasions, severe abdominal cramps, fever, shock, and delirium can all be symptoms.[2][11][12][13]

In extreme cases, people may pass more than one liter of fluid per hour. More often, individuals will complain of diarrhea with blood, accompanied by abdominal pain, rectal pain and a low-grade fever. Rapid weight loss and muscle aches sometimes also accompany dysentery, while nausea and vomiting are rare. On rare occasions, the amoebic parasite will invade the body through the bloodstream and spread beyond the intestines. In such cases, it may more seriously infect other organs such as the brain, lungs, and most commonly the liver.[14]

Mechanism

._Coloured_Wellcome_V0009858ER.jpg)

Dysentery results from bacterial, or parasitic infections. Viruses do not generally cause the disease.[7] These pathogens typically reach the large intestine after entering orally, through ingestion of contaminated food or water, oral contact with contaminated objects or hands, and so on.

Each specific pathogen has its own mechanism or pathogenesis, but in general, the result is damage to the intestinal linings, leading to the inflammatory immune responses. This can cause elevated physical temperature, painful spasms of the intestinal muscles (cramping), swelling due to fluid leaking from capillaries of the intestine (edema) and further tissue damage by the body's immune cells and the chemicals, called cytokines, which are released to fight the infection. The result can be impaired nutrient absorption, excessive water and mineral loss through the stools due to breakdown of the control mechanisms in the intestinal tissue that normally remove water from the stools, and in severe cases, the entry of pathogenic organisms into the bloodstream. Anemia may also arise due to the blood loss through diarrhea.

Bacterial infections that cause bloody diarrhea are typically classified as being either invasive or toxogenic. Invasive species cause damage directly by invading into the mucosa. The toxogenic species do not invade, but cause cellular damage by secreting toxins, resulting in bloody diarrhea. This is also in contrast to toxins that cause watery diarrhea, which usually do not cause cellular damage, but rather they take over cellular machinery for a portion of life of the cell.[15]

Some microorganisms – for example, bacteria of the genus Shigella – secrete substances known as cytotoxins, which kill and damage intestinal tissue on contact. Shigella is thought to cause bleeding due to invasion rather than toxin, because even non-toxogenic strains can cause dysentery, but E. coli with shiga-like toxins do not invade the intestinal mucosa, and are therefore toxin dependent.

Definitions of dysentery can vary by region and by medical specialty. The U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) limits its definition to "diarrhea with visible blood".[16] Others define the term more broadly.[17] These differences in definition must be taken into account when defining mechanisms. For example, using the CDC definition requires that intestinal tissue be so severely damaged that blood vessels have ruptured, allowing visible quantities of blood to be lost with defecation. Other definitions require less specific damage.

Amoebic dysentery

Amoebiasis, also known as amoebic dysentery, is caused by an infection from the amoeba Entamoeba histolytica,[18] which is found mainly in tropical areas.[19] Proper treatment of the underlying infection of amoebic dysentery is important; insufficiently treated amoebiasis can lie dormant for years and subsequently lead to severe, potentially fatal, complications.

When amoebae inside the bowel of an infected person are ready to leave the body, they group together and form a shell that surrounds and protects them. This group of amoebae is known as a cyst, which is then passed out of the person's body in the feces and can survive outside the body. If hygiene standards are poor – for example, if the person does not dispose of the feces hygienically – then it can contaminate the surroundings, such as nearby food and water. If another person then eats or drinks food or water that has been contaminated with feces containing the cyst, that person will also become infected with the amoebae. Amoebic dysentery is particularly common in parts of the world where human feces are used as fertilizer. After entering the person's body through the mouth, the cyst travels down into the stomach. The amoebae inside the cyst are protected from the stomach's digestive acid. From the stomach, the cyst travels to the intestines, where it breaks open and releases the amoebae, causing the infection. The amoebae can burrow into the walls of the intestines and cause small abscesses and ulcers to form. The cycle then begins again.

Bacillary dysentery

Dysentery may also be caused by shigellosis, an infection by bacteria of the genus Shigella, and is then known as bacillary dysentery (or Marlow syndrome). The term bacillary dysentery etymologically might seem to refer to any dysentery caused by any bacilliform bacteria, but its meaning is restricted by convention to Shigella dysentery.

Other bacteria

Some strains of Escherichia coli cause bloody diarrhea. The typical culprits are enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, of which O157:H7 is the best known.

Diagnosis

A clinical diagnosis may be made by taking a history and doing a brief examination. Treatment is usually started without or before confirmation by laboratory analysis.

Physical exam

The mouth, skin, and lips may appear dry due to dehydration. Lower abdominal tenderness may also be present.[14]

Stool and blood tests

Cultures of stool samples are examined to identify the organism causing dysentery. Usually, several samples must be obtained due to the number of amoebae, which changes daily.[14] Blood tests can be used to measure abnormalities in the levels of essential minerals and salts.[14]

Prevention

Efforts to prevent dysentery include hand washing and food safety measures well traveling in areas of high risk.[4]

Vaccine

Although there is currently no vaccine which protects against Shigella infection, several are in development.[20][21] Vaccination may eventually become a part of the strategy to reduce the incidence and severity of diarrhea, particularly among children in low-resource settings. For example, Shigella is a longstanding World Health Organization (WHO) target for vaccine development, and sharp declines in age-specific diarrhea/dysentery attack rates for this pathogen indicate that natural immunity does develop following exposure; thus, vaccination to prevent this disease should be feasible. The development of vaccines against these types of infection has been hampered by technical constraints, insufficient support for coordination, and a lack of market forces for research and development. Most vaccine development efforts are taking place in the public sector or as research programs within biotechnology companies.

Treatment

Dysentery is managed by maintaining fluids using oral rehydration therapy. If this treatment cannot be adequately maintained due to vomiting or the profuseness of diarrhea, hospital admission may be required for intravenous fluid replacement. In ideal situations, no antimicrobial therapy should be administered until microbiological microscopy and culture studies have established the specific infection involved. When laboratory services are not available, it may be necessary to administer a combination of drugs, including an amoebicidal drug to kill the parasite, and an antibiotic to treat any associated bacterial infection.

If shigellosis is suspected and it is not too severe, letting it run its course may be reasonable — usually less than a week. If the case is severe, antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin or TMP-SMX may be useful. However, many strains of Shigella are becoming resistant to common antibiotics, and effective medications are often in short supply in developing countries. If necessary, a doctor may have to reserve antibiotics for those at highest risk for death, including young children, people over 50, and anyone suffering from dehydration or malnutrition.

Amoebic dysentery is often treated with two antimicrobial drugs such as metronidazole and paromomycin or iodoquinol.[22]

Prognosis

With correct treatment, most cases of amoebic and bacterial dysentery subside within 10 days, and most individuals achieve a full recovery within two to four weeks after beginning proper treatment. If the disease is left untreated, the prognosis varies with the immune status of the individual patient and the severity of disease. Extreme dehydration can delay recovery and significantly raises the risk for serious complications.[23]

Epidemiology

Insufficient data exists, but Shigella is estimated to have caused the death of 34,000 children under the age of five in 2013, and 40,000 deaths in people over five years of age.[20] Amoebiasis infects over 50 million people each year, of whom 50,000 die.[24]

History

The seed, leaves, and bark of the kapok tree have been used in traditional medicine by indigenous peoples of the rainforest regions in the Americas, west-central Africa, and Southeast Asia in this disease.[25][26][27] Bacillus subtilis was marketed throughout America and Europe from 1946 as an immunostimulatory aid in the treatment of gut and urinary tract diseases such as rotavirus and Shigella,[28] but declined in popularity after the introduction of consumer antibiotics.

Notable cases

- 685 – Constantine IV, the Byzantine emperor, died of dysentery in September 685.

- 1183 – Henry the Young King died of dysentery at the castle of Martel on 11 June 1183.

- 1216 – King John of England died of dysentery at Newark Castle on 18 October 1216.[29]

- 1270 – Saint Louis IX of France died of dysentery in Tunis while commanding his troops for the Eighth Crusade on 25 September 1270.

- 1307 – King Edward I of England caught dysentery on his way to the Scottish border and died in his servants' arms on 6 July 1307.

- 1322 – King Philip V of France died of dysentery at the Abbey of Longchamp (site of the present hippodrome in the Bois de Boulogne) in Paris while visiting his daughter, Blanche, who had taken her vows as a nun there in 1322. He died on January 3, 1322.

- 1376 – Edward the Black Prince son of Edward III of England and heir to the English throne. Died of apparent dysentery in June, after a months-long period of illness during which he predicted his own imminent death, in his 46th year.

- 1422 – King Henry V of England died suddenly on 31 August 1422 at the Château de Vincennes, apparently from dysentery,[30] which he had contracted during the siege of Meaux. He was 35 years old and had reigned for nine years.

- 1536 – Erasmus, Dutch renaissance humanist and theologian. At Basel.[31]

- 1596 – Sir Francis Drake, vice admiral, died of dysentery on 28 January 1596 whilst anchored off the coast of Portobelo.[32]

- 1605 – Akbar, ruler of the Mughal Empire of South Asia, died of dysentery. On 3 October 1605, he fell ill with an attack of dysentery, from which he never recovered. He is believed to have died on or about 27 October 1605, after which his body was buried at a mausoleum in Agra, present-day India.[33]

- 1675 – Jacques Marquette died of dysentery on his way north from what is today Chicago, traveling to the mission where he intended to spend the rest of his life.[34]

- 1676 – Nathaniel Bacon died of dysentery after taking control of Virginia following Bacon's Rebellion. He is believed to have died in October 1676, allowing Virginia's ruling elite to regain control.[35]

- 19th century – As late as the nineteenth century, the 'bloody flux' it is estimated, killed more soldiers and sailors than did combat.[17] Typhus and dysentery decimated Napoleon's Grande Armée in Russia. More than 80,000 Union soldiers died of dysentery during the American Civil War.[36]

- 1827 – Queen Nandi kaBhebhe, (mother of Shaka Zulu) died of dysentery on October 10, 1827.[37]

- 1896 – Phan Đình Phùng, a Vietnamese revolutionary who led rebel armies against French colonial forces in Vietnam, died of dysentery as the French surrounded his forces on January 21, 1896.[38]

- 1930 – The French explorer and writer, Michel Vieuchange, died of dysentery in Agadir on 30 November 1930, on his return from the "forbidden city" of Smara. He was nursed by his brother, Doctor Jean Vieuchange, who was unable to save him. The notebooks and photographs, edited by Jean Vieuchange, went on to become bestsellers.[39][40]

- 1942 – The Selarang Barracks incident in the summer of 1942 during World War II involved the forced crowding of 17,000 Anglo-Australian prisoners-of-war (POWs) by their Japanese captors in the areas around the barracks square for nearly five days with little water and no sanitation after the Selarang Barracks POWs refused to sign a pledge not to escape. The incident ended with the surrender of the Australian commanders due to the spreading of dysentery among their men.[41]

See also

- Cholera, a bacterial infection of the small intestine which produces severe diarrhea.

References

- "Dysentery". who.int. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Dysentery" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- "WHO EMRO | Dysentery | Health topics". www.emro.who.int. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- "Dysentery". nhs.uk. 18 October 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Marie, C; Petri WA, Jr (30 August 2013). "Amoebic dysentery". BMJ clinical evidence. 2013. PMID 23991750.

- "Dysentery (Shigellosis)" (PDF). WHO. November 2016. p. 2. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- "Controlling the Spread of Infections|Health and Safety Concerns". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Tribble, DR (September 2017). "Antibiotic Therapy for Acute Watery Diarrhea and Dysentery". Military medicine. 182 (S2): 17–25. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-17-00068. PMID 28885920.

- Shirley, DT; Farr, L; Watanabe, K; Moonah, S (July 2018). "A Review of the Global Burden, New Diagnostics, and Current Therapeutics for Amebiasis". Open forum infectious diseases. 5 (7): ofy161. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofy161. PMID 30046644.

- Grove, David (2013). Tapeworms, Lice, and Prions: A compendium of unpleasant infections. OUP Oxford. p. PT517. ISBN 9780191653452.

- DuPont, H. L. (1978). "Interventions in diarrheas of infants and young children". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 173 (5 Pt 2): 649–53. PMID 359524.

- DeWitt, T. G. (1989). "Acute diarrhoea in children". Pediatr Rev. 11 (1): 6–13. doi:10.1542/pir.11-1-6. PMID 2664748.

- "Dysentery symptoms". National Health Service. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- "Dysentery-Diagnosis". mdguidelines.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- Ryan, Jason (2016). Boards and Beyond: Infectious Disease (Version 9-26-2016 ed.).

- "Laboratory Methods for the Diagnosis of Epidemic Dysentery and Cholera" (PDF). WHO/CDS/CSR/EDC/99.8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, Georgia 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2012.

- "Dysentery". TheFreeDictionary's Medical dictionary.

- WHO (1969). "Amoebiasis. Report of a WHO Expert Committee". WHO Technical Report Series. 421: 1–52. PMID 4978968.

- Amebic+Dysentery at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Mani, Sachin; Wierzba, Thomas; Walker, Richard I (2016). "Status of vaccine research and development Shigella". Vaccine. 34 (26): 2887–2894. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.075. PMID 26979135.

- "WHO vaccine pipeline tracker". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 25 July 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Chapter 3 Infectious Diseases Related To Travel". CDC. 1 August 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- mdguidelines.com. "Dysentery-Prognosis". Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1.

- "Kapok Tree". Blue Planet and Biomoes. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- "Ceiba pentandra". Human Uses and Cultural Importance. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- "Kapok Emergent Tree Of Tropical Rain Forest Used To Treat Asthma Dysentery Fever Kidney Diseases". encyclocenter.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- Mazza, P. (1994). "The use of Bacillus subtilis as an antidiarrhoeal microorganism". Boll. Chim. Farm. 133 (1): 3–18. PMID 8166962.

- Warren, W. Lewis (1991). King John. London: Methuen. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-413-45520-8.

- "BBC – History – Henry V". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

-

- "BBC – History – Sir Francis Drake". bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- Majumdar 1984, pp. 168–169

- Archived March 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Foner, Eric (2012). Give Me Liberty! An American History (brief ed.). New York, London: W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 9780393920321.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). The encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars: a political, social, and military history. ABC–CLIO. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1.

- cite Morris, Donald R. (1998). The Washing of the Spears: A History of the Rise of the Zulu Nation Under Shaka and Its Fall in the Zulu War of 1879

- Marr, David G. (1970). Vietnamese anticolonialism, 1885–1925. Berkeley, California: University of California. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-520-01813-6.

- Meaux, Antoine de (2004). L'ultime désert: vie et mort de Michel Vieuchange (in French). Paris: Phébus. pp. 29, 245–249 & 253. ISBN 978-2-85940-997-5.

- Vieuchange, Michel (1988) [1932]. Smara: The Forbidden City. Fletcher Allen, Edgar (translation); Vieuchange, Jean (editor; introduction, notes, postscript); Claudel, Paul (preface). (Reprinted ed.). New York: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-88001-146-4.

- Thompson, Peter (2005). The Battle For Singapore—The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II. United Kingdom: Portraits Books. pp. 389–390. ISBN 978-0-7499-5085-9.

External links

| Classification |

|---|