Intussusception (medical disorder)

Intussusception is a medical condition in which a part of the intestine folds into the section immediately ahead of it.[1] It typically involves the small bowel and less commonly the large bowel.[1] Symptoms include abdominal pain which may come and go, vomiting, abdominal bloating, and bloody stool.[1] It often results in a small bowel obstruction.[1] Other complications may include peritonitis or bowel perforation.[1]

| Intussusception | |

|---|---|

| An intussuception as seen on CT | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, general surgery |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, vomiting, bloody stool[1] |

| Complications | Peritonitis, bowel perforation[1] |

| Usual onset | Over days to weeks in a 6 to 18 month old[1] |

| Causes | Unknown, lead point[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pyloric stenosis[1] |

| Treatment | Enema, surgery[1] |

| Medication | Dexamethasone[2] |

The cause in children is typically unknown; in adults a lead point is sometimes present.[1] Risk factors in children include certain infections, diseases like cystic fibrosis, and intestinal polyps.[1] Risk factors in adults include endometriosis, bowel adhesions, and intestinal tumors.[1] Diagnosis is often supported by medical imaging.[1] In children, ultrasound is preferred while in adults a CT scan is preferred.[1]

Intussusception is an emergency requiring rapid treatment.[1] Treatment in children is typically by an enema with surgery used if this is not successful.[1] Dexamethasone may decrease the risk of another episode.[2] In adults, surgical removal of part of the bowel is more often required.[1] Intussusception occurs more commonly in children than adults.[1] In children, males are more often affected than females.[1] The usual age of occurrence is six to eighteen months old.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Early symptoms can include periodic abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting (sometimes green in color from bile), pulling legs to the chest area, and intermittent moderate to severe cramping abdominal pain. Pain is intermittent—not because the intussusception temporarily resolves, but because the intussuscepted bowel segment transiently stops contracting. Later signs include rectal bleeding, often with "red currant jelly" stool (stool mixed with blood and mucus), and lethargy. Physical examination may reveal a "sausage-shaped" mass, felt upon palpating the abdomen.[3] Children, or those unable to communicate symptoms verbally, may cry, draw their knees up to their chest, or experience dyspnea (difficult or painful breathing) with paroxysms of pain.

Fever is not a symptom of intussusception. However, intussusception can cause a loop of bowel to become necrotic, secondary to ischemia due to compression to arterial blood supply. This leads to perforation and sepsis, which causes fever.

In rare cases, intussusception may be a complication of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), an immune-mediated vasculitis disease in children. Such patients who develop intussusception often present with severe abdominal pain in addition to the classic signs and symptoms of HSP.

Cause

Causes of intussusception are not clearly established or understood. About 90% of cases of intussusception in children arise from an unknown cause.[1] They can include infections, anatomical factors, and altered motility.

While an earlier version of the rotavirus vaccine was linked to intussusception, the current versions is not.[4]

Pathophysiology

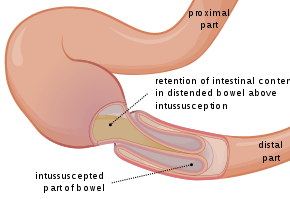

In the most frequent type of intussusception, the ileum enters the cecum. However, other types occur, such as when a part of the ileum or jejunum prolapses into itself.

The part that prolapses into the other is called the intussusceptum, and the part that receives it is called the intussuscipiens. Almost all intussusceptions occur with the intussusceptum having been located proximally to the intussuscipiens. This is because peristaltic action of the intestine pulls the proximal segment into the distal segment. There are, however, rare reports of the opposite being true.

An anatomic lead point (that is, a piece of intestinal tissue that protrudes into the bowel lumen) is present in approximately 10% of intussusceptions.[5]

The trapped section of bowel may have its blood supply cut off, which causes ischemia (lack of oxygen in the tissues). The mucosa (gut lining) is very sensitive to ischemia, and responds by sloughing off into the gut. This creates the classically described "red currant jelly" stool, which is a mixture of sloughed mucosa, blood, and mucus.[6] A study reported that in actuality, only a minority of children with intussusception had stools that could be described as "red currant jelly", and hence intussusception should be considered in the differential diagnosis of children passing any type of bloody stool.[7]

Diagnosis

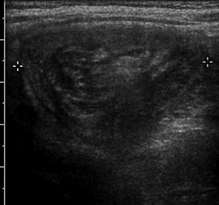

An intussusception is often suspected based on history and physical exam, including observation of Dance's sign. A digital rectal examination is particularly helpful in children, as part of the intussusceptum may be felt by the finger. A definite diagnosis often requires confirmation by diagnostic imaging modalities. Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis and exclusion of intussusception, due to its high accuracy and lack of radiation. The appearance of target sign (also called "doughnut sign" on a sonograph, usually around 3 cm in diameter, confirms the diagnosis. The image seen on transverse sonography or computed tomography is that of a doughnut shape, created by the hyperechoic central core of bowel and mesentery surrounded by the hypoechoic outer edematous bowel.[9] In longitudinal imaging, intussusception resembles a sandwich.[9]

An x-ray of the abdomen may be indicated to check for intestinal obstruction or free intraperitoneal gas. The latter finding implies that bowel perforation has already occurred. Some institutions use air enema for diagnosis, as the same procedure can be used for treatment.[10]

Classification

- Ileoileal – 4%

- Ileocolic (or ileocecal) – 77%

- Ileo-ileo-colic – 12%

- Colocolic – 2%

- Multiple – 1%

- Retrograde – 0.2%

- Others – 2.8%[11]

In children, insussusception at the ileocecal junction and accounts for 90 percent of all cases.[12]

Differential diagnosis

An intussusception has two main differential diagnoses: acute gastroenteritis and rectal prolapse. Abdominal pain, vomiting, and stool with mucus and blood are present in acute gastroenteritis, but diarrhea is the leading symptom. Rectal prolapse can be differentiated by projecting mucosa that can be felt in continuity with the perianal skin, whereas in intussusception the finger may pass indefinitely into the depth of the sulcus.

Treatment

The condition is not usually immediately life-threatening. The intussusception can be treated with either a barium or water-soluble contrast enema or an air-contrast enema, which both confirms the diagnosis of intussusception, and in most cases successfully reduces it.[13] The success rate is over 80%. However, approximately 5–10% of these recur within 24 hours.

Cases where it cannot be reduced by an enema or the intestine is damaged require surgical reduction. In a surgical reduction, the surgeon opens the abdomen and manually squeezes (rather than pulls) the part that has telescoped. If the surgeon cannot successfully reduce it, or the bowel is damaged, they resect the affected section. More often, the intussusception can be reduced by laparoscopy, pulling the segments of intestine apart with forceps.

Prognosis

Intussusception may become a medical emergency if not treated early, as it eventually causes death if not reduced. In developing countries where medical hospitals are not easily accessible, especially when other problems complicate the intussusception, death becomes almost inevitable. When intussusception or any other severe medical problem is suspected, the person must be taken to a hospital immediately.

The outlook for intussusception is excellent when treated quickly, but when untreated it can lead to death within two to five days. It requires fast treatment, because the longer the intestine segment is prolapsed the longer it goes without bloodflow, and the less effective a non-surgical reduction is. Prolonged intussusception also increases the likelihood of bowel ischemia and necrosis, requiring surgical resection.

Epidemiology

The condition is diagnosed most often in infancy and early childhood. It strikes about 2,000 infants (one in every 1,900) in the United States in the first year of life. Its incidence begins to rise at about one to five months of life, peaks at four to nine months of age, and then gradually declines at around 18 months.

Intussusception occurs more frequently in boys than in girls, with a ratio of approximately 3:1.[14]

In adults, intussusception represents the cause of approximately 1% of bowel obstructions and is frequently associated with neoplasm, malignant or otherwise.[15]

References

- Marsicovetere, P; Ivatury, SJ; White, B; Holubar, SD (February 2017). "Intestinal Intussusception: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 30 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1593429. PMC 5179276. PMID 28144210.

- Gluckman, S; Karpelowsky, J; Webster, AC; McGee, RG (1 June 2017). "Management for intussusception in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD006476. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006476.pub3. PMC 6481850. PMID 28567798.

- Cera, SM (2008). "Intestinal Intussusception". Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 21 (2): 106–13. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1075859. ISSN 1531-0043. PMC 2780199. PMID 20011406.

- Lu, Hai-Ling; Ding, Ying; Goyal, Hemant; Xu, Hua-Guo (4 October 2019). "Association Between Rotavirus Vaccination and Risk of Intussusception Among Neonates and Infants". JAMA Network Open. 2 (10): e1912458. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12458.

- Chapter X.4. Intussusception Archived 2012-08-26 at the Wayback Machine from Case Based Pediatrics For Medical Students and Residents, by Lynette L. Young, MD. Department of Pediatrics, University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine. December 2002

- Toso C, Erne M, Lenzlinger PM, Schmid JF, Büchel H, Melcher G, Morel P (2005). "Intussusception as a cause of bowel obstruction in adults" (PDF). Swiss Med Wkly. 135 (5–6): 87–90. PMID 15729613. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-24.

- Yamamoto, LG; Morita, SY; Boychuk, RB; Inaba, AS; Rosen, LM; Yee, LL; Young, LL (May 1997). "Stool appearance in intussusception: assessing the value of the term "currant jelly."". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 15 (3): 293–8. doi:10.1016/s0735-6757(97)90019-x. PMID 9148991.

- "UOTW #4 Answer - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- Park NH, Park SI, Park CS, Lee EJ, Kim MS, Ryu JA, Bae JM (2007). "Ultrasonographic findings of small bowel intussusception, focusing on differentiation from ileocolic intussusception". Br J Radiol. 80 (958): 798–802. doi:10.1259/bjr/61246651. ISSN 0007-1285. PMID 17875595.

- C Surendranath Singh; M.l. Prakash (28 Jul 2011). "Adult Intussception : A Case Report". Webmed Central. doi:10.9754/journal.wmc.2011.002052. ISSN 2046-1690. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- Bailey & Love's/24th/1195

- Nghia "Jack" Vo, Thomas T Sato. "Intussusception in children". UpToDate. Retrieved 2017-12-06. Topic 5898 Version 37.0

- Chowdhury SH, Cozma AI, Chowdhury JH. Abdominal Pain in Pediatrics. Essentials for the Canadian Medical Liscensing Exam: Review and Prep for MCCQE Part I. 2nd edition. Wolters Kluwer. Hong Kong. 2017.

- Lonnie King (2006). "Pediatrics: Intussusception". Archived from the original on 2006-05-18. Retrieved 2006-06-05.

- Gayer G, Zissin R, Apter S, Papa M, Hertz M (2002). "Pictorial review: adult intussusception--a CT diagnosis". Br J Radiol. 75 (890): 185–90. PMID 11893645. Archived from the original on 2010-05-09.

Further reading

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |