Cholestasis

Cholestasis is a condition where bile cannot flow from the liver to the duodenum. The two basic distinctions are an obstructive type of cholestasis where there is a mechanical blockage in the duct system that can occur from a gallstone or malignancy, and metabolic types of cholestasis which are disturbances in bile formation that can occur because of genetic defects or acquired as a side effect of many medications.

| Cholestasis | |

|---|---|

| |

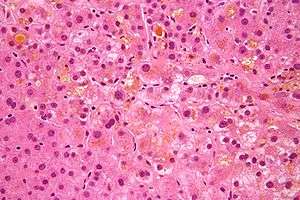

| Micrograph showing bile (yellow) stasis, i.e. cholestasis. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

Signs and symptoms

- Itchiness (pruritus). Pruritus is the primary symptom of cholestasis and is thought to be due to interactions of serum bile acids with opioidergic nerves. In fact, the opioid antagonist naltrexone is used to treat pruritus due to cholestasis.

- Jaundice. Jaundice is an uncommon occurrence in intrahepatic (metabolic) cholestasis, but is common in obstructive cholestasis.

- Pale stool. This symptom implies obstructive cholestasis.

- Dark urine

Causes

Possible causes:

- pregnancy

- androgens

- birth control pills

- antibiotics (such as TMP/SMX)

- abdominal mass (e.g. cancer)

- biliary atresia and other pediatric liver diseases

- biliary trauma

- congenital anomalies of the biliary tract

- gallstones

- acute hepatitis

- cystic fibrosis

- intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (obstetric cholestasis)

- primary biliary cholangitis, an autoimmune disorder

- primary sclerosing cholangitis, associated with inflammatory bowel disease

- some drugs (e.g. flucloxacillin and erythromycin)

Drugs such as gold salts, nitrofurantoin, anabolic steroids, chlorpromazine, prochlorperazine, sulindac, cimetidine, erythromycin, estrogen, and statins can cause cholestasis and may result in damage to the liver.

Mechanism

Bile is secreted by the liver to aid in the digestion of fats. Bile formation begins in bile canaliculi that form between two adjacent surfaces of liver cells (hepatocytes) similar to the terminal branches of a tree. The canaliculi join each other to form larger and larger structures, sometimes referred to as the canals of Hering, which themselves join to form small bile ductules that have an epithelial surface. The ductules join to form bile ducts that eventually form either the right main hepatic duct that drains the right lobe of the liver, or the left main hepatic duct draining the left lobe of the liver. The two ducts join to form the common hepatic duct, which in turn joins the cystic duct from the gall bladder, to give the common bile duct. This duct then enters the duodenum at the ampulla of Vater.

In cholestasis, bile accumulates in the hepatic parenchyma.[1]

Diagnosis

Cholestasis can be suspected when there is an elevation of both 5'-nucleotidase and ALP enzymes. With a few exceptions, the optimal test for cholestasis would be elevations of serum bile acid levels. However, this is not normally available in most clinical settings. The gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) enzyme was previously thought to be helpful in confirming a hepatic source of ALP; however, GGT elevations lack the necessary specificity to be a useful confirmatory test for ALP. Normally GGT and ALP are anchored to membranes of hepatocytes and are released in small amounts in hepatocellular damage. In cholestasis, synthesis of these enzymes is induced and they are made soluble. GGT is elevated because it leaks out from the bile duct cells due to pressure from inside bile ducts.

In a later stage of cholestasis AST, ALT and unconjugated bilirubin may be elevated due to hepatocyte damage as a secondary effect of cholestasis.

Histopathology

Under a microscope, the individual hepatocytes will have a brownish-green stippled appearance within the cytoplasm, representing bile that cannot get out of the cell. Canalicular bile plugs between individual hepatocytes or within bile ducts may also be seen, representing bile that has been excreted from the hepatocytes but cannot go any further due to the obstruction. When these plugs occur within the bile duct, sufficient pressure (caused by bile accumulation) can cause them to rupture, spilling bile into the surrounding tissue, causing hepatic necrosis. These areas are known as bile lakes, and are typically seen only with extra-hepatic obstruction.

Management

Extrahepatic cholestasis can usually be treated by surgery. Pruritis in cholestatic jaundice is treated by antihistamines, ursodeoxycholic acid, and phenobarbital. Nalfurafine hydrochloride can also treat pruritus caused by chronic liver disease and was recently approved in Japan for this purpose.

See also

- Jaundice

- Liver function tests

- Lipoprotein-X - an abnormal low density lipoprotein found in cholestasis

- Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

- Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

- Feathery degeneration - a histopathologic finding associated with cholestasis

References

- Kumar (2015). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (9 ed.). Elsevier. pp. 821–881.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |