Alcoholic hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis is hepatitis (inflammation of the liver) due to excessive intake of alcohol.[1] It is usually found in association with fatty liver, an early stage of alcoholic liver disease, and may contribute to the progression of fibrosis, leading to cirrhosis. Signs and symptoms of alcoholic hepatitis include jaundice, ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity), fatigue and hepatic encephalopathy (brain dysfunction due to liver failure). Mild cases are self-limiting, but severe cases have a high risk of death. Severe cases may be treated with glucocorticoids.

| Alcoholic hepatitis | |

|---|---|

| |

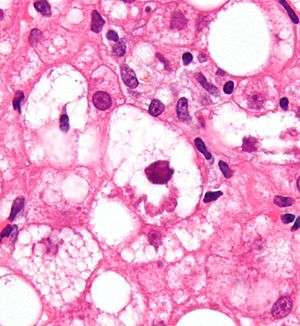

| Micrograph showing a Mallory body, a histopathologic finding associated with alcoholic hepatitis. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

Signs and symptoms

Alcoholic hepatitis is characterized by a myriad of symptoms, which may include feeling unwell, enlargement of the liver, development of fluid in the abdomen (ascites), and modest elevation of liver enzyme levels (as determined by liver function tests). Alcoholic hepatitis can vary from mild with only liver enzyme elevation to severe liver inflammation with development of jaundice, prolonged prothrombin time, and even liver failure. Severe cases are characterized by either obtundation (dulled consciousness) or the combination of elevated bilirubin levels and prolonged prothrombin time; the mortality rate in both severe categories is 50% within 30 days of onset.

Alcoholic hepatitis is distinct from cirrhosis caused by long-term alcohol consumption. Alcoholic hepatitis can occur in patients with chronic alcoholic liver disease and alcoholic cirrhosis. Alcoholic hepatitis by itself does not lead to cirrhosis, but cirrhosis is more common in patients with long term alcohol consumption. Some alcoholics develop acute hepatitis as an inflammatory reaction to the cells affected by fatty change. This is not directly related to the dose of alcohol. Some people seem more prone to this reaction than others. This is called alcoholic steatonecrosis and the inflammation probably predisposes to liver fibrosis.

Pathophysiology

Some signs and pathological changes in liver histology include:

- Mallory's hyaline body – a condition where pre-keratin filaments accumulate in hepatocytes. This sign is not limited to alcoholic liver disease, but is often characteristic.[2]

- Ballooning degeneration – hepatocytes in the setting of alcoholic change often swell up with excess fat, water and protein; normally these proteins are exported into the bloodstream. Accompanied with ballooning, there is necrotic damage. The swelling is capable of blocking nearby biliary ducts, leading to diffuse cholestasis.[2]

- Inflammation – neutrophilic invasion is triggered by the necrotic changes and presence of cellular debris within the lobules. Ordinarily the amount of debris is removed by Kupffer cells, although in the setting of inflammation they become overloaded, allowing other white cells to spill into the parenchyma. These cells are particularly attracted to hepatocytes with Mallory bodies.[2]

If chronic liver disease is also present:

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made in a patient with history of significant alcohol intake who develops worsening liver function tests, including elevated bilirubin and aminotransferases. The ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase is usually 2 or more.[3] In most cases, the liver enzymes do not exceed 500. The changes on liver biopsy are important in confirming a clinical diagnosis.

Management

Clinical practice guidelines have recommended corticosteroids.[4] People should be risk stratified using a MELD Score or Child-Pugh score.

- Corticosteroids: These guidelines suggest that patients with a modified Maddrey's discriminant function score > 32 or hepatic encephalopathy should be considered for treatment with prednisolone 40 mg daily for four weeks followed by a taper.[4] Models such as the Lille Model can be used to monitor for improvement or to consider alternative treatment.

- Pentoxifylline: A randomized controlled trial found that among patients with a discriminant function score > 32 and at least one of the following symptoms (a palpable, tender enlarged liver, fever, high white blood cell count, hepatic encephalopathy, or hepatic systolic bruit), 4.6 patients must be treated with pentoxifylline for 4 weeks to prevent one patient from dying.[5] Subsequent trials have suggested that pentoxifylline may be superior to prednisolone in the management of acute alcoholic hepatitis with discriminant function score >32. Advantages of pentoxifylline over prednisolone include better tolerability, fewer side effects, with decreased occurrence of kidney dysfunction in patients receiving pentoxifylline.[6]

- Potential for combined therapy: A large prospective study of over 1000 patients investigated whether prednisolone and pentoxifylline produced benefits when used alone or in combination.[7] Pentoxifylline did not improve survival alone or in combination. Prednisolone gave a small reduction in mortality at 28 days but this did not reach significance, and there were no improvements in outcomes at 90 days or 1 year.

See also

- AST/ALT ratio

- Lille Model

- Steatohepatitis

References

- "Alcoholic liver disease: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2017-01-02.

- Cotran; Kumar, Collins (1998). Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia: W.B Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-7335-X.

- Sorbi D, Boynton J, Lindor KD (1999). "The ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase: potential value in differentiating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis from alcoholic liver disease". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 94 (4): 1018–22. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01006.x. PMID 10201476.

- McCullough AJ, O'Connor JF (1998). "Alcoholic liver disease: proposed recommendations for the American College of Gastroenterology". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 93 (11): 2022–36. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00587.x. PMID 9820369.

- Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O (2000). "Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Gastroenterology. 119 (6): 1637–48. doi:10.1053/gast.2000.20189. PMID 11113085. (ACP Journal Club synopsis)

- De BK, Gangopadhyay S, Dutta D, Baksi SD, Pani A, Ghosh P (2009). "Pentoxifylline versus prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis: a randomized controlled trial". World J. Gastroenterol. 15 (13): 1613–9. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.1613. PMC 2669113. PMID 19340904.

- Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, Downs N, Gleeson D, MacGilchrist A, Grant A, Hood S, Masson S, McCune A, Mellor J, O'Grady J, Patch D, Ratcliffe I, Roderick P, Stanton L, Vergis N, Wright M, Ryder S, Forrest EH (2015). "Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis". N. Engl. J. Med. 372 (17): 1619–28. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1412278. PMID 25901427.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |