List of benzodiazepines

The below tables contain a sample list of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine analogs that are commonly prescribed, with their basic pharmacological characteristics, such as half-life and equivalent doses to other benzodiazepines, also listed, along with their trade names and primary uses. The elimination half-life is how long it takes for half of the drug to be eliminated by the body. "Time to peak" refers to when maximum levels of the drug in the blood occur after a given dose. Benzodiazepines generally share the same pharmacological properties, such as anxiolytic, sedative, hypnotic, skeletal muscle relaxant, amnesic, and anticonvulsant effects. Variation in potency of certain effects may exist amongst individual benzodiazepines. Some benzodiazepines produce active metabolites. Active metabolites are produced when a person's body metabolizes the drug into compounds that share a similar pharmacological profile to the parent compound and thus are relevant when calculating how long the pharmacological effects of a drug will last. Long-acting benzodiazepines with long-acting active metabolites, such as diazepam and chlordiazepoxide, are often prescribed for benzodiazepine or alcohol withdrawal as well as for anxiety if constant dose levels are required throughout the day. Shorter-acting benzodiazepines are often preferred for insomnia due to their lesser hangover effect.[1][2][3][4][5]

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

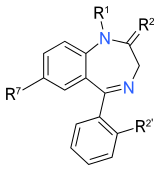

The core structure of benzodiazepines. "R" labels denote common locations of side chains, which give different benzodiazepines their unique properties. |

It is fairly important to note that elimination half-life of diazepam and chlordiazepoxide, as well as other long half-life benzodiazepines, is twice as long in the elderly compared to younger individuals. Individuals with an impaired liver also metabolize benzodiazepines more slowly. Many doctors make the mistake of not adjusting benzodiazepine dosage according to age in elderly patients. Thus, the approximate equivalent of doses below may need to be adjusted accordingly in individuals on short acting benzodiazepines who metabolize long-acting benzodiazepines more slowly and vice versa. The changes are most notable with long acting benzodiazepines as these are prone to significant accumulation in such individuals. For example, the equivalent dose of diazepam in an elderly individual on lorazepam may be half of what would be expected in a younger individual.[6][7] Equivalencies between individual benzodiazepines can differ by 400 fold on a mg per mg basis; awareness of this fact is necessary for the safe and effective use of benzodiazepines.[8]

Pharmacokinetic properties of various benzodiazepines

Data in the table below is taken from the Ashton "Benzodiazepine Equivalency Table".[4][9][10][11]

| Drug name | Common trade names[lower-alpha 1] | Year approved (US FDA) | Approx. equivalent oral doses to 10 mg diazepam[lower-alpha 2] (mg) | Time to peak onset of action

(hours) |

Elimination half-life of active metabolite (hours) | Therapeutic use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adinazolam | Deracyn | Research chemical | 1–2 | 3 | anxiolytic, antidepressant | |

| Alprazolam | Xanax, Helex, Xanor, Trankimazin, Onax, Alprox, Misar, Restyl, Solanax, Tafil, Neurol, Frontin, Kalma, Ksalol | 1981 | 0.5 | 1–2 | 10–20 | anxiolytic, antidepressant |

| Bentazepam[lower-alpha 3] | Thiadipona | 1–3 | 2–4 | anxiolytic | ||

| Bretazenil[13] | 2.5 | anxiolytic, anticonvulsant | ||||

| Bromazepam | Lectopam, Lexaurin, Lexatin, Lexotanil, Lexotan, Bromam | 1981 | 6 | 1–3 | 20–40 | anxiolytic, |

| Bromazolam | Research chemical | anxiolytic | ||||

| Brotizolam[lower-alpha 4] | Lendormin, Dormex, Sintonal, Noctilan | 0.5–2 | 4–5 | hypnotic | ||

| Camazepam | Albego, Limpidon, Paxor | 0.5–2 | 6–29 | anxiolytic | ||

| Chlordiazepoxide | Librium, Risolid, Elenium | 1960 | 25 | 1.5–4 | 5–200 | anxiolytic |

| Cinazepam | Levana | 2–4 | 60 | hypnotic, anxiolytic | ||

| Cinolazepam | Gerodorm | 0.5–2 | 9 | hypnotic | ||

| Clobazam | Onfi, Frisium, Urbanol | 2011 | 1–3 | 8–60 | anxiolytic, anticonvulsant | |

| Clonazepam | Rivatril, Rivotril, Klonopin, Iktorivil, Paxam | 1975 | 0.5 | 1–4 | 19.5–50 | anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, muscle relaxant |

| Clonazolam | Research chemical | 0.2 | 0.5–1.5 | 10–18 | anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, muscle relaxant | |

| Clorazepate | Tranxene, Tranxilium | 1972 | 20 | Variable | 32–152 | anxiolytic, anticonvulsant |

| Clotiazepam[lower-alpha 3] | Veratran, Clozan, Rize | 1–3 | 4 | anxiolytic | ||

| Cloxazolam | Sepazon, Olcadil | 2–5 | 80–105 | anxiolytic, anticonvulsant | ||

| Delorazepam | Dadumir | 1–2 | 80–105 | anxiolytic, amnesic | ||

| Deschloroetizolam[lower-alpha 4] | Research chemical | anxiolytic | ||||

| Diazepam | Antenex, Apaurin, Apzepam, Apozepam, Diazepan, Hexalid, Normabel, Pax, Stesolid, Stedon, Tranquirit, Valium, Vival, Valaxona | 1963 | 10 | 1–1.5 | 32–205 | anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, muscle relaxant, amnesic |

| Diclazepam[14] | Research chemical | 1.5–3 | 42 | anxiolytic, amnesic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, muscle relaxant | ||

| Estazolam | ProSom, Nuctalon | 1990 | 1–5 | 10–31 | hypnotic, anxiolytic | |

| Ethyl carfluzepate | Not approved | 1–5 | 11–24 | hypnotic | ||

| Etizolam[lower-alpha 4] | Etilaam, Etizest, Pasaden, Depas | Often sold as a research chemical, but is approved for human use in many countries. Controlled substance in some US states, Canada, Germany, Austria, and others.[15][16] | 1–2 | 1–2 | 6 | anxiolytic, hypnotic, amnesic, muscle relaxant, anticonvulsant |

| Ethyl loflazepate | Victan, Meilax, Ronlax | 2.5–3 | 73–119 | anxiolytic | ||

| Flualprazolam | Research chemical | hypnotic, anxiolytic | ||||

| Flubromazepam[17] | Research chemical | 1.5–8 | 100–220 | anxiolytic, hypnotic, amnesic, muscle relaxant, anticonvulsant | ||

| Flubromazolam | Research chemical | hypnotic | ||||

| Fluclotizolam[lower-alpha 4] | Research chemical | hypnotic | ||||

| Flunitrazepam | Rohypnol, Hipnosedon, Vulbegal, Fluscand, Flunipam, Ronal, Rohydorm, Hypnodorm | Not approved | 1 | 0.5–3 | 18–200 | hypnotic |

| Flunitrazolam | Research chemical | hypnotic | ||||

| Flurazepam | Dalmadorm, Dalmane, Fluzepam | 1970 | 15 | 1–1.5 | 40–250 | hypnotic |

| Flutazolam | Coreminal | 3.5 | hypnotic | |||

| Flutoprazepam | Restas | Research chemical | 0.5–9 | 60–90 | hypnotic, anticonvulsant | |

| Halazepam | Paxipam | 1981 | 20 | 1–3 | 30–100 | anxiolytic |

| Ketazolam | Anxon | Not approved | 20 | 2.5–3 | 30–200 | anxiolytic |

| Loprazolam | Dormonoct | 1.5 | 0.5–4 | 3–15 | hypnotic | |

| Lorazepam | Ativan, Orfidal, Lorenin, Lorsilan, Temesta, Tavor, Lorabenz | 1977 | 1 | 2–4 | 10–20 | anxiolytic, amnesic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, muscle relaxant[18][11][19] |

| Lormetazepam | Loramet, Noctamid, Pronoctan | 1 | 0.5–2 | 10 | hypnotic | |

| Meclonazepam | Research chemical | anxiolytic | ||||

| Medazepam | Nobrium, Ansilan, Mezapam, Rudotel, Raporan | 10 | 1–1.5 | 36–200 | anxiolytic | |

| Metizolam[lower-alpha 4] | Research chemical | 2–4 | 12 | anxiolytic, hypnotic, amnesic, muscle relaxant, anticonvulsant | ||

| Mexazolam | Melex, Sedoxil | 1–2 | anxiolytic | |||

| Midazolam | Dormicum, Versed, Hypnovel, Dormonid | 1985 | 10 (oral)

4 (IV) |

0.5–1 | 1.5–2.5 | hypnotic, anticonvulsant, amnesic |

| Nifoxipam | Research chemical | hypnotic | ||||

| Nimetazepam | Erimin | 0.5–3 | 14–30 | hypnotic | ||

| Nitemazepam | Research chemical | |||||

| Nitrazepam | Mogadon, Alodorm, Pacisyn, Dumolid, Nitrazadon | 1965 | 10 | 0.5–3 | 17–48 | hypnotic, anticonvulsant |

| Nitrazolam | Research chemical | hypnotic | ||||

| Nordiazepam | Madar, Stilny | 30–150 | anxiolytic | |||

| Norflurazepam | Research chemical | hypnotic | ||||

| Oxazepam | Seresta, Serax, Serenid, Serepax, Sobril, Oxabenz, Oxapax, Oxascand, Ox-Pam, Opamox, Alepam, Medopam, Murelax, Noripam, Purata | 1965 | 25 | 3–4 | 4–11 | anxiolytic |

| Phenazepam | Phenazepam | Research chemical | 1.5–4 | 60 | anxiolytic, anticonvulsant | |

| Pinazepam | Domar | 40–100 | anxiolytic | |||

| Prazepam | Lysanxia, Centrax | Not approved | 15 | 2–6 | 36–200 | anxiolytic |

| Premazepam | Not approved | 2–6 | 10–13 | anxiolytic | ||

| Pyrazolam | Research chemical | 1–1.5 | 16–18[20] | anxiolytic, amnesic | ||

| Quazepam | Doral | 1985 | 20 | 1–5 | 39–120 | hypnotic |

| Rilmazafone | Rhythmy | 11 | hypnotic | |||

| Temazepam | Restoril, Normison, Euhypnos, Temaze, Tenox | 1981 | 20 | 0.5–3 | 4–11 | hypnotic, anxiolytic, muscle relaxant |

| Tetrazepam | Myolastan | 1–3 | 3–26 | muscle relaxant | ||

| Triazolam | Halcion, Rilamir | 1982 | 0.25 | 0.5–2 | 2 | hypnotic |

Atypical benzodiazepine receptor ligands

| Drug name | Common trade names | Year approved (US FDA) | Elimination half-life

of active metabolite (hours) |

Therapeutic use |

| DMCM | anxiogenic, convulsant | |||

| Flumazenil[lower-alpha 5] | Anexate, Lanexat, Mazicon, Romazicon | 1 | antidote | |

| Eszopiclone§ | Lunesta | 2004 | 6 | hypnotic |

| Zaleplon§ | Sonata, Starnoc | 1999 | 1 | hypnotic |

| Zolpidem§ | Ambien, Nytamel, Sanval, Stilnoct, Stilnox, Sublinox (Canada), Xolnox, Zoldem, Zolnod | 1992 | 2.6 | hypnotic |

| Zopiclone§ | Imovane, Rhovane, Ximovan; Zileze; Zimoclone; Zimovane; Zopitan; Zorclone, Zopiklone | 4–6 | hypnotic |

- Not all trade names are listed.

- An alternative table published by the state of South Australia uses equivalent approximate oral dosages to 5 mg diazepam.[12]

- Technically this is a thienodiazepine, but produces very similar effects as benzodiazepines.

- Technically this is a thienotriazolodiazepine, but produces very similar effects as benzodiazepines.

- Flumazenil is an imidazobenzodiazepine derivative,[21] and in layman's terms, it is a benzodiazepine overdose antidote that is given intravenously in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) to reverse the effects of benzodiazepine overdoses, as well for overdoses of the non-benzodiazepine "Z-drugs" such as zolpidem.[22] Flumazenil is contraindicated for benzodiazepine-tolerant patients in overdose cases.[23] In such cases, the benefits are far outweighed by the risks, which include potential and severe seizures.[21][24] The method by which flumazenil acts to prevent non-benzodiazepine tolerant overdose from causing potential harm is via preventing the benzodiazepines and Z-drugs from binding to the GABAA receptors via competitive inhibition which the flumazenil creates. Clinical observation notating the patient's oxygen levels, respiratory, heart and blood pressure rates are used, as they are much safer than the potential seizure effects from flumazenil. Supportive care to mediate any problems resulting from abnormal rates of the pulmonary, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems is typically the only treatment that is required in benzodiazepine-only overdoses.[25] In most cases, activated charcoal/carbon is often used to prevent benzodiazepines from being absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract, and the use of stomach-pumping/gastric lavage is no longer commonly used nor suggested by some toxicologists.[26] Even in cases where other central nervous system (CNS) depressants (such as in combined benzodiazepine and tricyclic antidepressant/TCA overdoses) are detected and/or suspected, endotrachial intubation for the airway path and supportive oxygen are typically implemented and are much safer than flumazenil.[25]

Controversy

The UK's House of Commons has attempted to get a two to four week limit mandate for prescribing benzodiazepines to replace the two to four week benzodiazepine prescribing guidelines, which are merely recommended.[27]

Binding data and structure-activity relationship

A large number of benzodiazepine derivatives have been synthesised and their structure-activity relationships explored in detail.[28][29] This chart contains binding data for benzodiazepines and related drugs investigated by Roche up to the late 1990s (though in some cases the compounds were originally synthesised by other companies such as Takeda or Upjohn).[30][31][32][33][34][35] Other benzodiazepines are also listed for comparison purposes,[36][37][38] but it does not however include binding data for;

- Benzodiazepines developed in the former Soviet Union (e.g. phenazepam, gidazepam etc.)

- Benzodiazepines predominantly used only in Japan (e.g. nimetazepam, flutoprazepam etc.)

- 4,5-cyclised benzodiazepines (e.g. ketazolam, cloxazolam etc.), and other compounds not researched by Roche

- Benzodiazepines developed more recently (e.g. remimazolam, QH-ii-066, Ro48-6791 etc.)

- "Designer" benzodiazepines for which in vitro binding data is unavailable (e.g. flubromazolam, pyrazolam etc.)[39][40][41][42][43]

While binding or activity data is available for most of these compounds also, the assay conditions vary between sources, meaning that in many cases the values are not suitable for a direct comparison. Many older sources used animal measures of activity (i.e. sedation or anticonvulsant activity) but did not measure in vitro binding to benzodiazepine receptors.[44][45] See for instance Table 2 vs Table 11 in the Chem Rev paper, Table 2 lists in vitro pIC50 values matching those below, while Table 11 has pEC50 values derived from in vivo assays in mice, which show the same activity trends but cannot be compared directly, and includes data for compounds such as diclazepam and flubromazepam which are not available in the main data set.

Also note;

- IC50 / pIC50 values represent binding affinity only and do not reflect efficacy or pharmacokinetics, and some compounds listed are GABAA antagonists rather than agonists (e.g. flumazenil).

- Low IC50 or high pIC50 values indicate tighter binding (pIC50 of 8.0 = IC50 of 10nM, pIC50 of 9.0 = IC50 of 1nM, etc.)

- These are non subtype selective IC50 values averaged across all GABAA receptor subtypes, so subtype selective compounds with strong binding at one subtype but weak at others will appear unusually weak due to averaging of binding values (see e.g. CL-218,872)

- Finally, note that the benzodiazepine core is a privileged scaffold, which has been used to derive drugs with diverse activity that is not limited to the GABAA modulatory action of the classical benzodiazepines,[46] such as devazepide and tifluadom, however these have not been included in the list below. 2,3-benzodiazepines such as tofisopam are also not listed, as these act primarily as AMPA receptor modulators, and are inactive at GABAA receptors.

References

- Golombok S, Lader M (August 1984). "The psychopharmacological effects of premazepam, diazepam and placebo in healthy human subjects". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 18 (2): 127–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02444.x. PMC 1463527. PMID 6148956.

- de Visser SJ, van der Post JP, de Waal PP, Cornet F, Cohen AF, van Gerven JM (January 2003). "Biomarkers for the effects of benzodiazepines in healthy volunteers" (PDF). Br J Clin Pharmacol. 55 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.t01-10-01714.x. PMC 1884188. PMID 12534639.

- "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- Ashton, C. Heather (March 2007). "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- Bob, Dr (July 1995). "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Charts". dr-bob.org. Archived from the original on 2009-02-09. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- Salzman, Carl (15 May 2004). Clinical geriatric psychopharmacology (4th ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 450–453. ISBN 978-0-7817-4380-8.

- Delcò F, Tchambaz L, Schlienger R, Drewe J, Krähenbühl S (2005). "Dose adjustment in patients with liver disease". Drug Saf. 28 (6): 529–45. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528060-00005. PMID 15924505.

- Riss, J.; Cloyd, J.; Gates, J.; Collins, S. (Aug 2008). "Benzodiazepines in epilepsy: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics". Acta Neurol Scand. 118 (2): 69–86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01004.x. PMID 18384456.

- "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Chart". www.mental-health-today.com.

- "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table". www.bcnc.org.uk. April 2007. Archived from the original on 2015-02-06.

- Farinde, Abimbola (31 July 2018). "Benzodiazepine Equivalency Table". Medscape.

- "Benzodiazepines Information for GPs" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Services South Australia.

- van Steveninck AL, et al. (1996). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions of bretazenil and diazepam with alcohol". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 41 (6): 565–573. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.38514.x. PMC 2042631. PMID 8799523.

- Moosmann, Bisel P, Auwärter V. (2014). "Characterization of the designer benzodiazepine diclazepam and preliminary data on its metabolism and pharmacokinetics". The National Center for Biotechnology. 6 (7–8): 757–63. doi:10.1002/dta.1628. PMID 24604775.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Health Santé Canada, Federal Government of Canada (January 20, 2012). "Status Decision of Controlled and Non-Controlled Substances" (PDF). Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA). 1: 2.

- Assembly, Indiana General. "House Bill 1019 - Controlled substances". Indiana General Assembly. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- J Mass Spectrom (2013). "Detection and identification of the designer benzodiazepine flubromazepam and preliminary data on its metabolism and pharmacokinetics". The National Center for Biotechnology. 48 (11): 1150–9. Bibcode:2013JMSp...48.1150M. doi:10.1002/jms.3279. PMID 24259203.

- Shah, Dhwani; Borrensen, Dorothy (2011). "Benzodiazepines: A Guide to Safe Prescribing" (PDF). The Carlat Report: Psychiatry.

- Vancouver Hospital Pharmaceutical Sciences. "Comparison of Benzodiazepines".

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-05. Retrieved 2014-11-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.gene.com/download/pdf/romazicon_prescribing.pdf

- "Flumazenil Injection, Solution [App Pharmaceuticals, Llc]". Dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- "DailyMed". Dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- Gary R. Fleisher; Stephen Ludwig; Benjamin K. Silverman (2002). Synopsis of pediatric emergency medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp 409. ISBN 978-0-7817-3274-1. Retrieved 3/22/2013.

- http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/pharm/pim181.htm#DivisionTitle:8.1.1.1 Toxicological analyses. Retrieved 3/21/2013.)

- Vale JA, Kulig K; American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. (2004). "Position paper: gastric lavage". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 42 (7): 933–943. doi:10.1081/CLT-200045006. PMID 15641639

- "APPG for Involuntary Tranquilliser Addiction". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- Sternbach Leo H (1979). "The benzodiazepine story". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 22 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1021/jm00187a001. PMID 34039.

- Hadjipavlou-Litina D, Hansch C (1994). "Quantitative structure-activity relationships of the benzodiazepines. a review and reevaluation". Chemical Reviews. 94 (6): 1483–1505. doi:10.1021/cr00030a002.

- Haefely, W; Kyburz, E; Gerecke, M; Mohler, H (1985). "Recent advances in the molecular pharmacology of benzodiazepine receptors and in the structure-activity relationships of their agonists and antagonists". Adv. Drug Res. 1985 (14): 165–322.

- A. Winkler, David; R. Burden, Frank; Watkins, Andrew J. R. (January 1998). "Atomistic Topological Indices Applied to Benzodiazepines using Various Regression Methods". Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships. 17 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3838(199801)17:01<14::AID-QSAR14>3.0.CO;2-U.

- Thakur, A; Thakur, M; Khadikar, P (17 November 2003). "Topological modeling of benzodiazepine receptor binding". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (23): 5203–7. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2003.08.014. PMID 14604684.

- So, SS; Karplus, M (1996). "Genetic neural networks for quantitative structure-activity relationships: improvements and application of benzodiazepine affinity for benzodiazepine/GABAA receptors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 39 (26): 5246–5256. doi:10.1021/jm960536o. PMID 8978853.

- Claus Braestrup and Mogens Nielsen. Benzodiazepine receptors. Biochemical Studies of CNS Receptors. Handbook of Psychopharmacology. (1983) Springer 2013. ISBN 9781468443615

- Zhang et al. Chemical and computer assisted development of an inclusive pharmacophore for the benzodiazepine receptor. Chapter 7, Biological Inhibitors. Volume 2 of Studies in medicinal chemistry. CRC Press, 2004. ISBN 9783718658794

- Obradović AL, et al. Sh-I-048A, an in vitro non-selective super-agonist at the benzodiazepine site of GABAA receptors: the approximated activation of receptor subtypes may explain behavioral effects. Brain Res. 2014 Mar 20;1554:36-48. PMID 24472579 doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.036

- Cornett EM, et al. New benzodiazepines for sedation. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2018 Jun;32(2):149-164. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2018.06.007 PMID 30322456

- Clayton T, et al. A Review of the Updated Pharmacophore for the Alpha 5 GABA(A) Benzodiazepine Receptor Model. Int J Med Chem. 2015; 2015: 430248. doi:10.1155/2015/430248 PMID 26682068

- Moosmann, Bjoern; King, Leslie A.; Auwärter, Volker (2015). "Designer benzodiazepines: A new challenge". World Psychiatry 14 (2): 248–248. doi:10.1002/wps.20236. ISSN 1723-8617

- Moosmann B., Auwärter V. (2018) Designer Benzodiazepines: Another Class of New Psychoactive Substances. In: Maurer H., Brandt S. (eds) New Psychoactive Substances. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology, vol 252. doi:10.1007/164_2018_154

- Manchester KR, et al. The emergence of new psychoactive substance (NPS) benzodiazepines: A review. Drug Testing and Analysis 2017 May; 10(1):1-17. doi:10.1002/dta.2211

- Waters L, Manchester KR, Maskell PD, Haegeman C, Haider S. The use of a quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) model to predict GABA-A receptor binding of newly emerging benzodiazepines. Science and Justice. 2018 Jan 8. doi:10.1016/j.scijus.2017.12.004

- Zawilska JB, Wojcieszak J. An expanding world of New Psychoactive Substances – Designer benzodiazepines. NeuroToxicology 2019 July; 73: 8-16. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2019.02.015

- Blair T, Webb GA (Sep 1977). "Electronic factors in the structure-activity relationship of some 1,4-benzodiazepin-2-ones". J Med Chem. 20 (9): 1206–10. doi:10.1021/jm00219a019. PMID 926122.

- Biagi GL, Barbaro AM, Guerra MC, Babbini M, Gaiardi M, Bartoletti M, Borea PA (Feb 1980). "Rm values and structure-activity relationship of benzodiazepines". J Med Chem. 23 (2): 193–201. doi:10.1021/jm00176a016. PMID 7359533.

- Spencer J, Rathnam RP, Chowdhry BZ. 1,4-Benzodiazepin-2-ones in medicinal chemistry. Future Med Chem. 2010 Sep;2(9):1441-9. doi:10.4155/fmc.10.226. PMID 21426139

Further reading

- Gitlow, Stuart (1 October 2006). Substance Use Disorders: A Practical Guide (2nd ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-7817-6998-3.

- Galanter, Marc; Kleber, Herbert D. (1 July 2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.). United States of America: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.