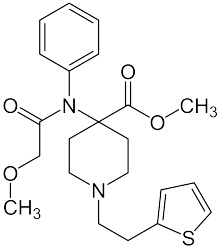

Thiafentanil

Thiafentanil (A-3080, Thianil) is a highly potent opioid analgesic that is an analog of fentanyl, and was invented in 1986.[1] It is similar to carfentanil though with a faster onset of effects, shorter duration of action and a slightly lesser tendency to produce respiratory depression. It is used in veterinary medicine to anesthetise large animals such as impala, usually in combination with other anesthetics such as ketamine, xylazine or medetomidine to reduce the prevalence of side effects such as muscle rigidity.[2]

| |

| Legal status | |

|---|---|

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H28N2O4S |

| Molar mass | 416.54 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Side effects

Side effects of fentanyl analogs are similar to those of fentanyl itself, which include itching, nausea and potentially serious respiratory depression, which can be life-threatening. Potent pure opioid antagonists such as naltrexone or nalmefene are recommended in the event of accidental human exposure to thiafentanil.[3] Fentanyl analogs have killed hundreds of people throughout Europe and the former Soviet republics since the most recent resurgence in use began in Estonia in the early 2000s, and novel derivatives continue to appear.[4] A new wave of fentanyl analogues and associated deaths began in around 2014 in the US, and have continued to grow in prevalence; especially since 2016 these drugs have been responsible for hundreds of overdose deaths every week.[5]

Legal status

Thiafentanil is a Schedule II controlled drug in the USA since August 2016.[6]

See also

References

- Bao-Shan Huang, Ross C. Terrell, Kirsten H. Deutsche, Linas V. Kudzma, Nhora L. Lalinde (22 April 1986). "Patent US4584303A - N-aryl-N-(4-piperidinyl)amides and pharmaceutical compositions and method employing such compounds". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Zeiler, Gareth E.; Meyer, Leith C. R. (5 September 2017). "Chemical capture of impala (Aepyceros melampus): A review of factors contributing to morbidity and mortality". Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 44 (5): 991–1006. doi:10.1016/j.vaa.2017.04.005. ISSN 1467-2987. PMID 29050999.

- Haymerle A, Fahlman A, Walzer C. Human exposures to immobilising agents: results of an online survey. Vet Rec. 2010 Aug 28;167(9):327-32. Haymerle, A.; Fahlman, A.; Walzer, C. (2010). "Human exposures to immobilising agents: Results of an online survey". Veterinary Record. 167 (9): 327–332. doi:10.1136/vr.c4191. PMID 20802186.

- Jane Mounteney; Isabelle Giraudon; Gleb Denissov; Paul Griffiths (July 2015). "Fentanyls: Are we missing the signs? Highly potent and on the rise in Europe". International Journal of Drug Policy. 26 (7): 626–631. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.04.003. PMID 25976511.

- Armenian, Patil; Vo, Kathy T.; Barr-Walker, Jill; Lynch, Kara L. (14 October 2017). "Fentanyl, fentanyl analogs and novel synthetic opioids: A comprehensive review" (PDF). Neuropharmacology. 134 (Pt A): 121–132. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.10.016. ISSN 0028-3908. PMID 29042317.

- Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice (26 August 2016). "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Thiafentanil Into Schedule II. Interim final rule with request for comments". Federal Register. 81 (166): 58834–58840. ISSN 0097-6326. PMID 27568479.