Procarbazine

Procarbazine is a chemotherapy medication used for the treatment of Hodgkin's lymphoma and brain cancers.[1] For Hodgkin's it is often used together with chlormethine, vincristine, and prednisone while for brain cancers such as glioblastoma multiforme it is used with lomustine and vincristine.[1] It is typically taken by mouth.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Matulane, Natulan, Indicarb, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682094 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (gel capsule), intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | liver, kidney |

| Elimination half-life | 10 minutes |

| Excretion | kidney |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.010.531 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

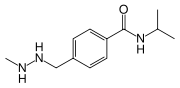

| Formula | C12H19N3O |

| Molar mass | 221.299 g/mol g·mol−1 |

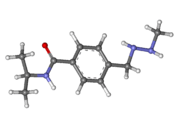

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| | |

Common side effect include low blood cell counts and vomiting.[1] Other side effects include tiredness and depression.[2][3] It is not recommended in people with severe liver or kidney problems.[4] Use in pregnancy is known to harm the baby.[1] Procarbazine is in the alkylating agents family of medication.[1] How it works is not clearly known.[1]

Procarbazine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1969.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[5] In the United Kingdom a month of treatment cost the NHS 450 to 750 pounds.[4]

Medical uses

When used to treat Hodgkin's lymphoma, it is often delivered as part of the BEACOPP regimen that includes bleomycin, etoposide, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine (tradename Oncovin), prednisone, and procarbazine. The first combination chemotherapy developed for Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL), MOPP also included procarbazine (ABVD has supplanted MOPP as standard first line treatment for HL, with BEACOPP as an alternative for advanced/unfavorable HL). Alternatively, when used to treat certain brain tumors (malignant gliomas), it is often dosed as PCV when combined with lomustine (often called CCNU) and vincristine.

Dose should be adjusted for kidney disease or liver disease.

Side effects

Very common (greater than 10% of people experience them) adverse effects include loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting.[2] Other side effects of unknown frequency include reduction in leukocytes, reduction in platelets, reduction in neutrophils, which can lead to increased infections including lung infections; severe allergy-like reactions that can lead to angioedema and skin reactions; lethargy; liver complications including jaundice and abnormal liver function tests; reproductive effects including reduction in sperm count and ovarian failure.[2]

When combined with ethanol, procarbazine may cause a disulfiram-like reaction in some people.[2]

It weakly inhibits MAO in the gastrointestinal system, so it can cause hypertensive crises if associated with the ingestion of tyramine-rich foods such as aged cheeses; this appears to be rare.[2]

Procarbazine rarely causes chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy,[6] a progressive, enduring, often irreversible tingling numbness, intense pain, and hypersensitivity to cold, beginning in the hands and feet and sometimes involving the arms and legs.[7]

Pharmacology

Its mechanism of action is not fully understood. Metabolism yields azo-procarbazine and hydrogen peroxide which results in the breaking of DNA strands.

References

- "Procarbazine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Procarbazine Capsules 50mg – Summary of Product Characteristics". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. 24 November 2014. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- WHO Model Formulary 2008 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. p. 228. ISBN 9789241547659. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 606. ISBN 9780857111562.

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Lisa M. DeAngelis; Jerome B. Posner (2003). "Nonmetastatic Complications". In Kufe DW; Pollock RE; Weichselbaum RR; et al. (eds.). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (6th ed.). Hamilton (ON): BC Decker. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- del Pino BM (Feb 23, 2010). "Chemotherapy-induced Peripheral Neuropathy". NCI Cancer Bulletin. 7 (4): 6. Archived from the original on 2011-12-11.