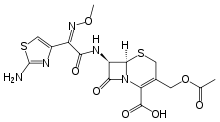

Cefotaxime

Cefotaxime is an antibiotic used to treat a number of bacterial infections.[2] Specifically it is used to treat joint infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, meningitis, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, sepsis, gonorrhea, and cellulitis.[2] It is given either by injection into a vein or muscle.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌsɛfəˈtækˌsiːm/[1] |

| Trade names | Claforan, others |

| Other names | cefotaxime sodium |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682765 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous and intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | n/a |

| Metabolism | liver |

| Elimination half-life | 0.8–1.4 hours |

| Excretion | 50–85% kidney |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.058.436 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H17N5O7S2 |

| Molar mass | 455.47 g/mol g·mol−1 |

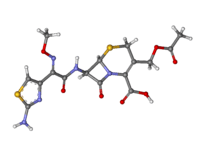

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include nausea, allergic reactions, and inflammation at the site of injection.[2] Another side effect may include Clostridium difficile diarrhea.[2] It is not recommended in people who have had previous anaphylaxis to a penicillin.[2] It is relatively safe for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[2][3] It is in the third-generation cephalosporin family of medications and works by interfering with the bacteria's cell wall.[2]

Cefotaxime was discovered in 1976 and came into commercial use in 1980.[4][5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.23–4.70 per dose.[7] In the United States a course of treatment costs $100–200.[3]

Medical uses

It is a broad-spectrum antibiotic with activity against numerous gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.

Given its broad spectrum of activity, cefotaxime is used for a variety of infections, including:

- Lower respiratory tract infections - e.g. pneumonia (most commonly caused by S. pneumoniae)

- Genitourinary system infections - urinary tract infections (e.g. E. coli, S. epidermidis, P. mirabilis) and cervical/urethral gonorrhea

- Gynecologic infections - e.g. pelvic inflammatory disease, endometritis, and pelvic cellulitis

- Sepsis - secondary to Streptococcus spp., S. aureus, E. coli, and Klebsiella spp.

- Intra-abdominal infections - e.g. peritonitis

- Bone and joint infections - S. aureus, Streptococcus spp.

- CNS infections - e.g. meningitis/ventriculitis secondary to N. meningitidis, H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae[8]

Although cefotaxime has demonstrated efficacy in these infections, it is not necessarily considered to be the first-line agent. In meningitis, cefotaxime crosses the blood–brain barrier better than cefuroxime.

Spectrum of activity

As a β-lactam antibiotic in the third-generation class of cephalosporins, cefotaxime is active against numerous Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including several with resistance to classic β-lactams such as penicillin. These bacteria often manifest as infections of the lower respiratory tract, skin, central nervous system, bone, and intra-abdominal cavity. While regional susceptibilities must always be considered, cefotaxime typically is effective against these organisms (in addition to many others):[8]

- Staphylococcus aureus (not including MRSA) and S. epidermidis

- Streptococcus pneumoniae and S. pyogenes

- Escherichia coli

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis

- Klebsiella spp.

- Burkholderia cepacia

- Proteus mirabilis and P. vulgaris

- Enterobacter spp.

- Bacteroides spp.

- Fusobacterium spp.

Notable organisms against which cefotaxime is not active include Pseudomonas and Enterococcus.[9] As listed, it has modest activity against the anaerobic Bacteroides fragilis.

The following represents MIC susceptibility data for a few medically significant microorganisms:

- H. influenzae: ≤0.007 - 0.5 µg/ml

- S. aureus: 0.781 - 172 µg/ml

- S. pneumoniae: ≤0.007 - 8 µg/ml

Historically, cefotaxime has been considered to be comparable to ceftriaxone (another third-generation cephalosporin) in safety and efficacy for the treatment of bacterial meningitis, lower respiratory tract infections, skin and soft tissue infections, genitourinary tract infections, and bloodstream infections, as well as prophylaxis for abdominal surgery.[12][13][14] The majority of these infections are caused by organisms traditionally sensitive to both cephalosporins. However, ceftriaxone has the advantage of once-daily dosing, whereas the shorter half-life of cefotaxime necessitates two or three daily doses for efficacy. Changing patterns in microbial resistance suggest cefotaxime may be suffering greater resistance than ceftriaxone, whereas the two were previously considered comparable.[15] Considering regional microbial sensitivities is also important when choosing any antimicrobial agent for the treatment of infection.

Adverse reactions

Cefotaxime is contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity to cefotaxime or other cephalosporins. Caution should be used and risks weighed against potential benefits in patients with an allergy to penicillin, due to cross-reactivity between the classes.

The most common adverse reactions experienced are:

- Pain and inflammation at the site of injection/infusion (4.3%)

- Rash, pruritus, or fever (2.4%)

- Colitis, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting (1.4%)[8]

Mechanism of action

Cefotaxime is a β-lactam antibiotic (which refers to the structural components of the drug molecule itself). As a class, β-lactams inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis by binding to one or more of the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). This inhibits the final transpeptidation step of peptidoglycan synthesis in bacterial cell walls, thus inhibiting cell wall biosynthesis. Bacteria eventually lyse due to ongoing activity of cell wall autolytic enzymes (autolysins and murein hydrolases) in the absence of cell wall assembly.[9] Due to the mechanism of their attack on bacterial cell wall synthesis, β-lactams are considered to be bactericidal.[8]

Unlike β-lactams such as penicillin and amoxicillin, which are highly susceptible to degradation by β-lactamase enzymes (produced, for example, nearly universally by S. aureus), cefotaxime boasts the additional benefit of resistance to β-lactamase degradation due to the structural configuration of the cefotaxime molecule. The syn-configuration of the methoxyimino moiety confers stability against β-lactamases.[16] Consequently, the spectrum of activity is broadened to include several β-lactamase-producing organisms (which would otherwise be resistant to β-lactam antibiotics), as outlined below.

Cefotaxime, like other β-lactam antibiotics, does not only block the division of bacteria, including cyanobacteria, but also the division of cyanelles, the photosynthetic organelles of the glaucophytes, and the division of chloroplasts of bryophytes. In contrast, it has no effect on the plastids of the highly developed vascular plants. This supports the endosymbiotic theory and indicates an evolution of plastid division in land plants.[17]

Administration

Cefotaxime is administered by intramuscular injection or intravenous infusion. As cefotaxime is metabolized to both active and inactive metabolites by the liver and largely excreted in the urine, dose adjustments may be appropriate in people with renal or hepatic impairment.[8][18][19]

Plant tissue culture

Cefotaxime is the only cephalosporin which has very low toxicity in plants, even at higher concentration (up to 500 mg/l). It is widely used to treat plant tissue infections with Gram-negative bacteria,[20] while vancomycin is used to treat the plant tissue infections with Gram-positive bacteria.[21][22]

See also

References

- "Cefotaxime". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Cefotaxime Sodium". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 87. ISBN 9781284057560.

- Walker, S. R. (2012). Trends and Changes in Drug Research and Development. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109. ISBN 9789400926592. Archived from the original on 2016-09-14.

- Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 494. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Cefotaxime". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Claforan Sterile (cefotaxime for injection, USP) and Injection (cefotaxime injection, USP). 19 June 2009. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-04-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Cefotaxime drug information Archived 2007-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-01-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.toku-e.com/Assets/MIC/Cefotaxime%20sodium%20USP.pdf%5B%5D%5B%5D

- Scholz H, Hofmann T, Noack R, Edwards DJ, Stoeckel K (1998). "Prospective comparison of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime for the short-term treatment of bacterial meningitis in children". Chemotherapy. 44 (2): 142–7. PMID 9551246.

- Woodfield JC, Van Rij AM, Pettigrew RA, van der Linden AJ, Solomon C, Bolt D (January 2003). "A comparison of the prophylactic efficacy of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime in abdominal surgery". American Journal of Surgery. 185 (1): 45–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(02)01125-X. PMID 12531444.

- Simmons BP, Gelfand MS, Grogan J, Craft B (1995). "Cefotaxime twice daily versus ceftriaxone once daily. A randomized controlled study in patients with serious infections". Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 22 (1–2): 155–7. doi:10.1016/0732-8893(95)00080-T. PMID 7587031.

- Gums JG, Boatwright DW, Camblin M, Halstead DC, Jones ME, Sanderson R (January 2008). "Differences between ceftriaxone and cefotaxime: microbiological inconsistencies". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 42 (1): 71–9. doi:10.1345/aph.1H620. PMID 18094350.

- Van TT, Nguyen HN, Smooker PM, Coloe PJ (March 2012). "The antibiotic resistance characteristics of non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica isolated from food-producing animals, retail meat and humans in South East Asia". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 154 (3): 98–106. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.12.032. PMID 22265849.

- Kasten B, Reski R (1997). "β-Lactam antibiotics inhibit chloroplast division in a moss (Physcomitrella patens) but not in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum)". Journal of Plant Physiology. 150 (1–2): 137–40. doi:10.1016/S0176-1617(97)80193-9. INIST:2640663.

- Bertels RA, Semmekrot BA, Gerrits GP, Mouton JW (October 2008). "Serum concentrations of cefotaxime and its metabolite desacetyl-cefotaxime in infants and children during continuous infusion". Infection. 36 (5): 415–20. doi:10.1007/s15010-008-7274-1. PMID 18791659.

- Coombes JD (1982). "Metabolism of cefotaxime in animals and humans". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 4 (Suppl 2): S325–32. doi:10.1093/clinids/4.Supplement_2.S325. JSTOR 4452886. PMID 6294781.

- cefotaxime for plant tissue culture Archived 2012-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- vancomycin for plant cell culture Archived 2012-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Pazuki, A; Asghari, J; Sohani, M; Pessarakli, M & Aflaki, F (2014). "Effects of Some Organic Nitrogen Sources and Antibiotics on Callus Growth of Indica Rice Cultivars" (PDF). Journal of Plant Nutrition. 38 (8): 1231–1240. doi:10.1080/01904167.2014.983118. Retrieved November 17, 2014.