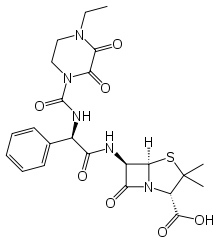

Piperacillin

Piperacillin is a broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotic of the ureidopenicillin class.[1] The chemical structure of piperacillin and other ureidopenicillins incorporates a polar side chain that enhances penetration into gram-negative bacteria and reduces susceptibility to cleavage by gram-negative beta lactamase enzymes. These properties confer activity against the important hospital pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Thus piperacillin is sometimes referred to as an "anti-pseudomonal penicillin".

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Pipracil |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | IV, IM |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 0% oral |

| Protein binding | 30% |

| Metabolism | Largely not metabolized |

| Elimination half-life | 36–72 minutes |

| Excretion | 20% in bile, 80% unchanged in urine |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.057.083 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H27N5O7S |

| Molar mass | 517.555 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

When used alone, piperacillin lacks strong activity against the gram-positive pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, as the beta-lactam ring is hydrolyzed by the bacteria's beta-lactamase.[2]

It was patented in 1974 and approved for medical use in 1981.[3] Piperacillin is most commonly used in combination with the beta-lactamase inhibitor tazobactam (piperacillin/Tazobactam), which enhances piperacillin's effectiveness by inhibiting many beta lactamases to which it is susceptible. However, the co-administration of tazobactam does not confer activity against MRSA, as penicillins (and most other beta lactams) do not avidly bind to the penicillin-binding proteins of this pathogen.[4]

Medical uses

Piperacillin is used almost exclusively in combination with the beta lactamase inhibitor tazobactam for the treatment of serious, hospital-acquired infections. This combination is among the most widely used drug therapies in United States non-federal hospitals, accounting for $388M in spending in spite of being a low-cost generic drug.[5]

Piperacillin-tazobactam is recommended as part of a three drug regimen for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia suspected as being due to infection by multi-drug resistant pathogens.[6] It is also one of several antibacterials recommended for the treatment of infections known to be caused by anaerobic gram-negative rods.[7]

Piperacillin-tazobactam is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence as initial empiric treatment for people with suspected neutropenic sepsis.[8]

Administration

Piperacillin is not absorbed orally, and must therefore be given by intravenous or intramuscular injection. It has been shown that the bactericidal actions of the drug do not increase with concentrations of piperacillin higher than 4-6 x MIC, which means that the drug is concentration-independent in terms of its actions. Piperacillin has instead shown to offer higher bactericidal activity when its concentration remains above the MIC for longer periods of time (50% time>MIC showing the highest activity). This higher activity present in continuous dosing has not been directly linked to clinical outcomes, but however does show promise of lowering possibility of resistance and decreasing mortality.[9]

References

- Tan JS, File TM (1995). "Antipseudomonal penicillins". Medical Clinics of North America. 79 (4): 679–93. PMID 7791416.

- Hauser, AR Antibiotic Basics for Clinicians, 2nd Ed., Wolters Kluwer, 2013, pg 26-27

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 491. ISBN 9783527607495.

- Zhanel GG, DeCorby M, Laing N, Weshnoweski B, Vashisht R, Tailor F, Nichol KA, Wierzbowski A, Baudry PJ, Karlowsky JA, Lagacé-Wiens P, Walkty A, McCracken M, Mulvey MR, Johnson J, Hoban DJ (2008). "Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in intensive care units in Canada: results of the Canadian National Intensive Care Unit (CAN-ICU) study, 2005-2006". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 52 (4): 1430–7. doi:10.1128/AAC.01538-07. PMC 2292546. PMID 18285482.

- Schumock GT, Li EC, Suda KJ, Wiest MD, Stubbings J, Matusiak LM, Hunkler RJ, Vermeulen LC (2015). "National trends in prescription drug expenditures and projections for 2015". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 72 (9): 717–36. doi:10.2146/ajhp140849. PMID 25873620.

- Mandell LA, Wunderink R, in Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 18th Ed., Chapter 257, pp. 2139-2141.

- Kasper DL, Cohen-Poradosu R, in Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 18th Ed., Chapter 164, pp. 1331-1339.

- "Neutropenic Sepsis: Prevention and Management of Neutropenic Sepsis in Cancer Patients". 2012. PMID 26065059. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lau W, Mercer D, Itani K, et al. (2006). "Randomized, open-label, comparative study of piperacillin-tazobactam administered by continuous infusion versus intermittent infusion for treatment of hospitalized patients with complicated intra-abdominal infection". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 50 (11): 3556–3561. doi:10.1128/AAC.00329-06. PMC 1635208. PMID 16940077.