2018–19 Kivu Ebola epidemic

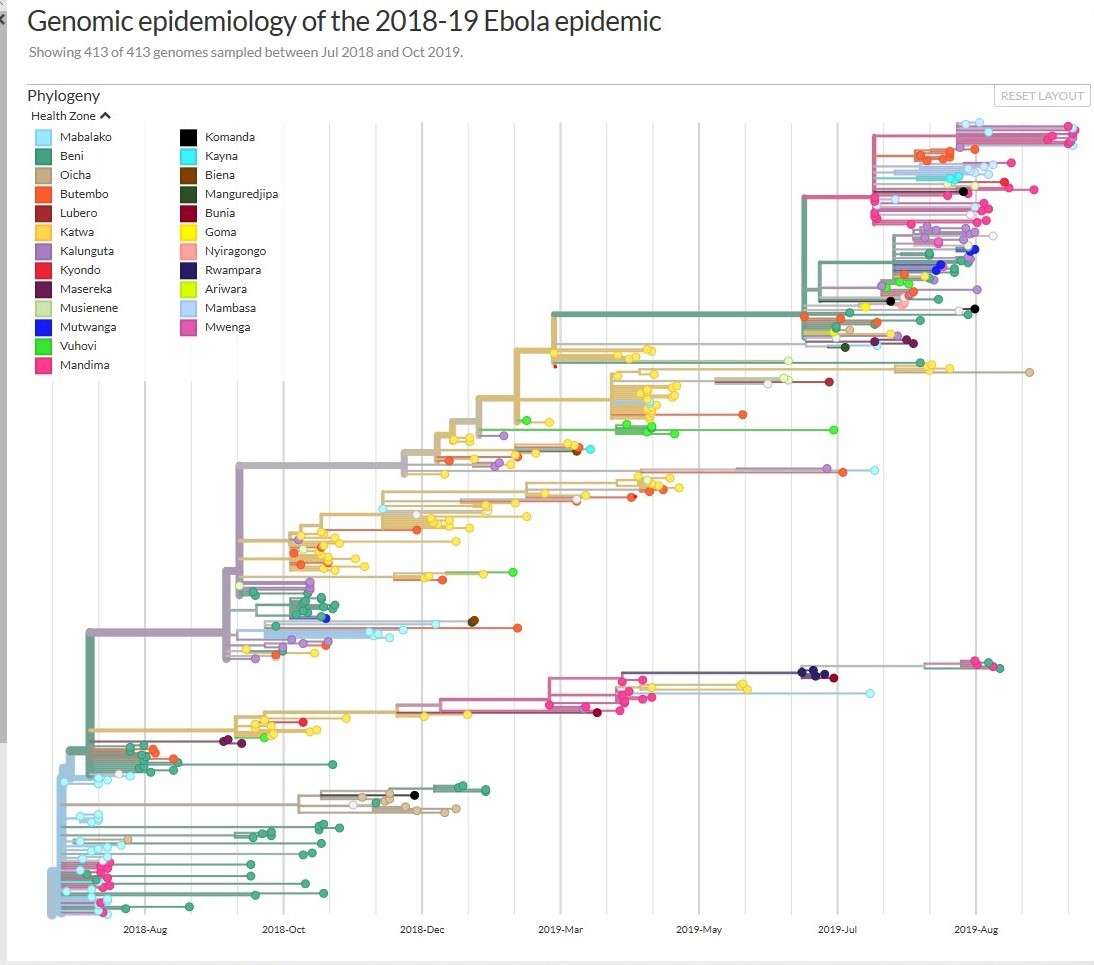

The 2018–19 Kivu Ebola epidemic[note 2] began on 1 August 2018, when it was confirmed that four cases had tested positive for Ebola virus disease (EVD) in the eastern region of Kivu in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).[9][10][11] The Kivu outbreak includes Ituri Province, after the first case was confirmed on 13 August,[8] and in June 2019, the virus reached Uganda, having infected a 5-year-old Congolese boy who entered Uganda with his family,[12] but was contained. In November 2018, the outbreak became the biggest Ebola outbreak in the DRC's history,[13][14][15] and by November, it had become the second-largest Ebola outbreak in recorded history,[16][17][18] behind only the 2013–2016 West Africa epidemic. On 3 May 2019, nine months into the outbreak, the DRC outbreak death toll surpassed 1,000.[19][20]

Democratic Republic of the Congo & Uganda | |||||||||||||||||

| Date | 1 August 2018–present | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casualties | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Since January 2015, the affected province and general area have been experiencing a military conflict, which is hindering treatment and prevention efforts. The World Health Organization (WHO) has described the combination of military conflict and civilian distress as a potential "perfect storm" that could lead to a rapid worsening of the outbreak.[21][22] In May 2019, the WHO reported that since January there had been 42 attacks on health facilities and 85 health workers had been wounded or killed. In some areas, aid organizations have had to stop their work due to violence.[23] Health workers also have to deal with misinformation spread by opposing politicians.[24]

Due to the deteriorating situation in North Kivu and surrounding areas, the WHO raised the risk assessment at the national and regional level from "high" to "very high" in September 2018.[25] In October, the United Nations Security Council stressed that all armed hostility should come to a stop in the DRC, to better fight the ongoing EVD outbreak.[26][27][28] A confirmed case in Goma triggered the decision by the WHO to convene an emergency committee for the fourth time,[29][30] and on 17 July 2019, they announced a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), the highest level of alarm the WHO can sound.[31]

On 15 September, some slowdown of EVD cases was noted by the WHO in DRC,[32] however contact tracing continued to be below 100%, then at 89%.[32] As of mid-October 2019 the transmission of the virus has significantly reduced; it is now confined to the Mandima region near where the outbreak began, and is only affecting 27 health zones in the DRC (down from a peak of 207).[33]

While those infected by EVD are afforded immunity, it has been suggested to have a finite duration.[34] On 31 October, it was reported that an EVD survivor who had been assisting at a treatment center in Beni had been reinfected with EVD and died; such an incident is unprecedented.[35]

Epidemiology

Democratic Republic of the Congo

On 1 August 2018, the North Kivu health division notified Congo's health ministry of 26 cases of hemorrhagic fever, including 20 deaths. Four of six samples were sent for analysis to the National Institute of Biological Research in Kinshasa. Four of the six came back positive for Ebola and an outbreak was declared on that date.[37][38] The index case is believed to have been the death and unsafe burial of a 65-year-old woman on 25 July in the town of Mangina; soon afterwards seven members of her immediate family died.[39] This outbreak started just days after the end of the outbreak in Équateur province.[40][41]

By 3 August, the virus had developed in multiple locations; cases were reported in five health zones – Beni, Butembo, Oicha, Musienene and Mabalako – in North Kivu province and additionally, Mandima and Mambasa in Ituri Province.[42] However, one month later there had been confirmed cases only in the Mabalako, Mandima, Beni and Oicha health zones. The five suspected cases in the Mambasa Health Zone proved not to be EVD; it was not possible to confirm the one probable case in the Musienene Health Zone and the two probable cases in the Butembo Health Zone. No new cases had been recorded in any of those health zones. The first confirmed case in Butembo was announced on 4 September, the same day that it was announced that one of the cases registered at Beni had actually come from the Kalunguta Health Zone.[43]

On 1 August, just after the Ebola epidemic had been declared, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) arrived in Mangina, the epicenter of the outbreak to mount a response against the outbreak.[44] On 2 August, Oxfam indicated it would be taking part in the response to this latest outbreak in the DRC.[45] On 4 August, the WHO indicated that the current situation in the DRC, due to several factors, warranted a "high risk assessment" at the national and regional level for public health.[46]

In November, it was reported that the EVD outbreak ran across two provinces (and 14 health zones). The Table 1. Timeline of reported cases reflects cases that were not able to have a laboratory test sample prior to burial as probable cases.[47] By 23 December, the EVD outbreak had spread to more health zones, and at that time 18 such areas had been affected.[48] The current population in DRC is more than 84,000,000 people.[49]

Transition to the 2nd biggest EVD outbreak

On 7 August 2018, the DRC Ministry of Public Health indicated that the total count had climbed to almost 90 cases,[50] and The Uganda Ministry of Health issued an alert for extra surveillance as the outbreak was just 100 kilometres (62 mi) away from its border.[51] Two days later the total count was nearly 100 cases.[52] On 16 August, the United Kingdom indicated it would help with EVD diagnosis and monitoring in the DRC.[53] On 17 August, the WHO reported that "contacts" numbered about 1,500 individuals, however there could be more in certain conflict zones in the DRC that can not be reached.[54] Some 954 contacts were successfully followed up on 18 August, however, Mandima Health Zone indicated resistance; as a consequence, contacts were not followed up there per the WHO.[55]

On 4 September, Butembo, a city with almost one million people and an international airport, logged its first fatality in the Ebola outbreak. The city of Butembo, in the DRC, has trade links to Uganda, which it borders.[56][43]

On 24 September, it was reported that all contact tracing and vaccinations would stop for the foreseeable future in Beni, due to an attack the day before by rebel groups that left several individuals dead.[57] On 25 September, Peter Salama of the WHO indicated that insecurity is obstructing efforts to stop the virus and believed a combination of factors could establish conditions for an epidemic.[58] On 18 October, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) raised its travelers' alert to the DRC from a level 1 to level 2 for all U.S. travelers.[59] On 26 October, the WHO indicated that half of confirmed cases were not showing any fever symptom, thus making diagnosis more difficult.[60]

According to a September 2018 Lancet survey, 25% of respondents in Beni and Butembo believed the Ebola outbreak to be a hoax. These beliefs correlated with decreased likelihood of seeking healthcare or agreeing to vaccination.[61]

On 6 November, the CDC indicated that the current outbreak in the east region of the DRC may not be containable due to several factors. This would be the first time since 1976 that an outbreak has not been able to be curbed.[62] Due to various situations surrounding the current EVD outbreak, WHO indicated on 13 November, that the viral outbreak would last at least six months.[63]

On 23 November, it was reported that due to a steady increase in cases, it is expected that the EVD outbreak in DRC will overtake the Uganda 2000 outbreak of 425 total cases, to become the second biggest EVD outbreak behind only the West Africa Ebola virus epidemic.[64][17] According to the available statistics, women are being infected at a higher rate, 60%, than their male counterparts due to the EVD outbreak, a report issued 4 December indicated.[65]

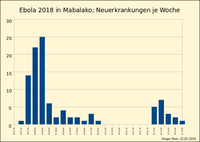

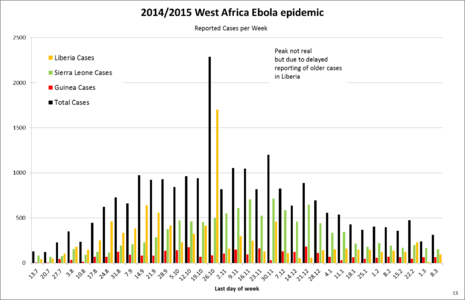

On 29 December, the DRC Ministry of Public Health declared "0 new confirmed cases detected because of the paralysis of the activities of the response in Beni, Butembo, Komanda and Mabalako" and no vaccination had occurred for three consecutive days.[66] On 22 January, the total case count began to approach 1,000 cases, (951 suspected) in the DRC Ministry of Public Health situation report.[67] The graphs below demonstrate the EVD intensity in different locations in the DRC, as well as in the West African epidemic of 2014–15 as a comparison:

Figure 3. New cases per week in Mabalako between 2018-07-16 and 2018-12-31

Figure 3. New cases per week in Mabalako between 2018-07-16 and 2018-12-31 Figure 4. New cases per week in town Beni between 2018-07-23 and 2019-01-28

Figure 4. New cases per week in town Beni between 2018-07-23 and 2019-01-28 Figure 5. New cases per week in Butembo (brown) and Katwa (yellow) between 2018-07-23 and 2019-02-04

Figure 5. New cases per week in Butembo (brown) and Katwa (yellow) between 2018-07-23 and 2019-02-04 Figure 6. West Africa Ebola epidemic cases per week, for comparison with current outbreak

Figure 6. West Africa Ebola epidemic cases per week, for comparison with current outbreak

On 16 March, the director of the CDC indicated that the outbreak in the DRC could last another year, additionally indicating that vaccine supplies could run out.[68] According to the WHO, resistance to vaccination in the Kaniyi Health Zone was ongoing as of March 2019.[69] There was still a belief by some in surrounding areas that the epidemic was a hoax.[70]

On 25 November, it was reported that violence had broken out in Beni once more, to such a degree that some aid agencies had evacuated. According to the same report some 300 individuals may have been exposed to EVD via an infected individual.[71]

Spread to Goma

On 14 July 2019, the first case of EVD was confirmed in the capital of North Kivu, Goma, a city with an international airport and a highly mobile population of 2 million people, which is right at the DRC's eastern border with Rwanda.[72][73][74][75] This case was a man who passed through three health checkpoints, with different names on traveller lists.[30] The WHO stated that he died in a treatment centre,[76] whereas according to Reuters he died en route to a treatment centre.[77] This case triggered the decision by the WHO to again reconvene an emergency committee,[29][30] at which the situation was officially announced as a PHEIC on 17 July 2019.[31]

On 30 July, a second case of EVD was confirmed in the city of Goma, apparently not linked to the first case,[78] and declared dead the following day.[79] Across the border from Goma in the country of Rwanda, Ebola simulation drills are being conducted at health facilities.[80] A third case of EVD was confirmed in Goma on 1 August.[81] On 22 August 2019, Nyiragongo Health Zone, the affected area on the outskirts of Goma, reached 21 days without further cases being confirmed.[82]

Spread to South Kivu Province

On 16 August 2019, it was reported that the Ebola virus disease had spread to a third province - South Kivu - via two new cases who had travelled from Beni, North Kivu.[83][84] By August 22, the number of cases in Mwenga had risen to four, including one person at a health facility visited by the first case.[85]

Uganda

On 13 August 2018, the DRC reported a total of 115 cases of the virus within its borders so far.[8][86] A UN agency indicated that steps were being taken to ensure that those leaving the DRC into Uganda were not infected with Ebola, this being done via active screening.[8][86] The government of Uganda opened two Ebola treatment centers at the border with the DRC, though there had not yet been any confirmed cases in the country of Uganda.[87][88] By 13 June 2019, nine treatment units were in place near the affected border.[89]

According to the International Red Cross, a "most likely scenario" entails an asymptomatic case will at some point enter the country of Uganda undetected among the numerous refugees coming from the DRC.[90] On 20 September, Uganda indicated it was ready for immediate vaccination, should the Ebola virus be detected in any individual.[91][92]

On 21 September, officials of the DRC indicated a confirmed case of EVD at Lake Albert, an entry point into Uganda, though no cases were then confirmed within Ugandan territory.[93][94]

On 2 November, it was reported that the Ugandan government would start vaccination of health workers along the border with the DRC as a proactive measure against the virus.[95] Vaccinations started on 7 November, and by 13 June 2019, 4,699 health workers at 165 sites had been vaccinated.[89] Proactive vaccination has also been carried out in South Sudan, with 1,471 health workers vaccinated by 7 May 2019.[96]

On 2 January 2019, it was reported that refugee movement from the DRC to Uganda had increased after the presidential elections.[97] On 12 February, it was reported that 13 individuals had been isolated due to their contact with a suspected Ebola case in Uganda;[98] the lab results came back negative several hours later.[99]

On 11 June 2019, the WHO reported that the virus had spread to Uganda. A 5-year-old Congolese boy entered Uganda on the previous Sunday with his family to seek medical care. On 12 June, the WHO reported that the 5-year-old patient had died, while 2 more cases of Ebola infection within the same family were also confirmed.[12][100] On 14 June it was reported that there were 112 contacts since EVD was first detected in Uganda.[101] Ring vaccination of Ugandan contacts was scheduled to start on 15 June.[28] As of 18 June 2019, 275 contacts have been vaccinated per the Uganda Ministry of Health.[102]

Other countries that border the DRC are South Sudan, Rwanda and Burundi,[103][104] as well as Angola, Zambia, Tanzania, Central African Republic and Republic of Congo, which are considered to have a lower risk of transmission.[89]

On 14 July, an individual entered the country of Uganda from DRC while symptomatic for EVD; there is an ongoing search for contacts in Mpondwe.[105] On 24 July, Uganda marked the needed 42 day period without any EVD cases to be declared Ebola-free.[106] On 29 August, a 9-year-old Congolese girl became the fourth individual in Uganda to test positive for EVD when she crossed from the DRC into the district of Kasese.[107]

Tanzania

In regards to possible EVD cases in Tanzania, the WHO stated on 21 September that "to date, the clinical details and the results of the investigation, including laboratory tests performed for differential diagnosis of these patients, have not been shared with WHO. The insufficient information received by WHO does not allow for a formulation of a hypotheses regarding the possible cause of the illness".[108][109][110] On 27 September, the CDC and U.S. State Department alerted potential travellers to the possibility of unreported EVD cases within Tanzania.[111] On 28 September, the United Kingdom began indicating to potential travelers to Tanzania, the undiagnosed death of an individual (and referencing the WHO, 21 September statement).[112]

The Tanzanian Health Minister Ummy Mwalimu stated on 3 October that there was no Ebola outbreak in Tanzania.[113] The WHO were provided with a preparedness update on 18 October which outlined a range of actions, and included commentary that since the outbreak commenced, there had been "29 alerts of Ebola suspect cases reported, 17 samples tested and were negative for Ebola (including 2 in September 2019)".[114]

Countries with medically evacuated individuals

On 29 December, an American physician who was exposed to the Ebola virus (and who was non-symptomatic) was evacuated, and taken to the University of Nebraska Medical Center.[115][116] On 12 January, the individual was released after 21 days without symptoms.[117]

| Table 1. Timeline of reported cases[118] | ||||||||

| Date | Cases # | Deaths | CFR | Contacts | Sources | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed | Probable | Suspected | Totals | |||||

| 2018-08-01†DRC | 4 | 22 | 0 | 26 | 20 | - | - | [119] |

| 2018-08-03 | 13 | 30 | 33 | 76 | 33 | 76.7%‡ | 879 | [120][121] |

| 2018-08-05 | 16 | 27 | 31 | 74 | 34 | 79%‡ | 966 | [122][123] |

| 2018-08-10 | 25 | 27 | 48 | 100 | 39 | 75%‡ | 953 | [124] |

| 2018-08-12 | 30 | 27 | 58 | 115 | 41 | - | 997 | [125] |

| 2018-08-17 | 64 | 27 | 12 | 103 | 50 | 55.6%‡ | 1,609 | [55] |

| 2018-08-20 | 75 | 27 | 9 | 111 | 59 | - | 2,408 | [126] |

| 2018-08-24 | 83 | 28 | 6 | 117 | 72 | 65%‡ | 3,421 | [127] |

| 2018-08-26 | 83 | 28 | 10 | 121 | 75 | 67.6%‡ | 2,445 | [128] |

| 2018-08-31 | 90 | 30 | 8 | 128 | 78 | 65%‡ | 2,462 | [129] |

| 2018-09-02 | 91 | 31 | 9 | 131 | 82 | - | 2,512 | [130] |

| 2018-09-07 | 100 | 31 | 14 | 145 | 89 | 68%‡ | 2,426 | [131] |

| 2018-09-09 | 101 | 31 | 9 | 141 | 91 | - | 2,265 | [132][133] |

| 2018-09-14 | 106 | 31 | 17 | 154 | 92 | 67.2%‡ | 1,751 | [134] |

| 2018-09-16 | 111 | 31 | 7 | 149 | 97 | - | 2,173 | [135][136] |

| 2018-09-21 | 116 | 31 | n/a | 147 | 99 | 67.3%‡ | 1,641 | [137] |

| 2018-09-23 | 119 | 31 | 9 | 159 | 100 | 67%‡ | 1,836 | [138] |

| 2018-09-28 | 126 | 31 | 23 | 180 | 102 | 65%‡ | 1,410 | [139] |

| 2018-10-02 | 130 | 32 | 17 | 179 | 106 | 65.4%‡ | 1,463 | [140] |

| 2018-10-05 | 142 | 35 | 11 | 188 | 113 | 63.8%‡ | 2,045 | [141] |

| 2018-10-07 | 146 | 35 | 21 | 202 | 115 | 63.5%‡ | 2,115 | [142] |

| 2018-10-12 | 176 | 35 | 32 | 243 | 135 | 64%‡ | 2,663 | [143] |

| 2018-10-15 | 181 | 35 | 32 | 248 | 139 | 64%‡ | 4,707 | [144] |

| 2018-10-19 | 202 | 35 | 33 | 270 | 153 | 65%‡ | 5,518 | [145] |

| 2018-10-21 | 203 | 35 | 14 | 252 | 155 | 65%‡ | 5,341 | [146] |

| 2018-10-26 | 232 | 35 | 43 | 310 | 170 | 64%‡ | 6,026 | [60] |

| 2018-10-28 | 239 | 35 | 32 | 306 | 174 | 63.5%‡ | 5,991 | [147] |

| 2018-11-02 | 263 | 35 | 70 | 368 | 186 | 62.4%‡ | 5,036 | [148] |

| 2018-11-04 | 265 | 35 | 61 | 361 | 186 | 62%‡ | 4,971 | [149] |

| 2018-11-09 | 294 | 35 | 60 | 389 | 205 | 62%‡ | 4,779 | [150] |

| 2018-11-11 | 295 | 38 | n/a | 333 | 209 | - | 4,803 | [151] |

| 2018-11-16 | 319 | 47 | 49 | 415 | 214 | 59%‡ | 4,430 | [152] |

| 2018-11-21 | 326 | 47 | 90 | 463 | 217 | - | 4,668 | [153] |

| 2018-11-23 | 365 | 47 | 45 | 457 | 236 | 57%‡ | 4,354 | [154] |

| 2018-11-26 | 374 | 47 | 74 | 495 | 241 | 57%‡ | 4,767 | [155] |

| 2018-11-30 | 392 | 48 | 63 | 503 | 255 | 58%‡ | 4,820 | [156] |

| 2018-12-03 | 405 | 48 | 79 | 532 | 268 | 59%‡ | 5,335 | [157] |

| 2018-12-07 | 446 | 48 | 95 | 589 | 283 | 57%‡ | 6,417 | [158] |

| 2018-12-10 | 452 | 48 | n/a | 500 | 289 | 58%‡ | 6,509 | [159] |

| 2018-12-14 | 483 | 48 | 111 | 642 | 313 | 59%‡ | 6,695 | [160] |

| 2018-12-21 | 526 | 48 | 118 | 692 | 347 | 60%‡ | 8,422 | [161] |

| 2018-12-28 | 548 | 48 | 52 | 648 | 361 | 61%‡ | 7,007 | [162] |

| 2019-01-04 | 575 | 48 | 118 | 741 | 374 | 60%‡ | 5,047 | [163] |

| 2019-01-11 | 595 | 49 | n/a | 644 | 390 | 61%‡ | 4,937 | [164] |

| 2019-01-18 | 636 | 49 | 209 | 894 | 416 | 61%‡ | 4,971 | [165][166] |

| 2019-01-25 | 679 | 54 | 204 | 937 | 459 | 63%‡ | 6,241 | [167][168] |

| 2019-02-01 | 720 | 54 | 168 | 942 | 481 | 62%‡ | >7,000 | [169][170] |

| 2019-02-10 | 750 | 61 | 148 | 959 | 510 | 63%‡ | 7,846 | [171][172] |

| 2019-02-18 | 773 | 65 | 135 | 973 | 534 | 64%‡ | 6,772 | [173][174] |

| 2019-02-24 | 804 | 65 | 219 | 1,088 | 546 | 63%‡ | 5,739 | [175][176] |

| 2019-03-03 | 830 | 65 | 182 | 1,077 | 561 | 63%‡ | 5,613 | [177][178] |

| 2019-03-10 | 856 | 65 | 191 | 1,112 | 582 | 63%‡ | 4,830 | [179][180] |

| 2019-03-17 | 886 | 65 | 231 | 1,182 | 598 | 63%‡ | 4,158 | [181][182] |

| 2019-03-25 | 944 | 65 | 226 | 1,235 | 629 | 62%‡ | 4,132 | [183][184] |

| 2019-03-31 | 1,016 | 66 | 279 | 1,361 | 676 | 62%‡ | 6,989 | [69][185] |

| 2019-04-07 | 1,080 | 66 | 282 | 1,428 | 721 | 63%‡ | 7,099 | [186] |

| 2019-04-14 | 1,185 | 66 | 269 | 1,520 | 803 | 64%‡ | 10,461 | [187] |

| 2019-04-21 | 1,270 | 66 | 92 | 1,428 | 870 | 65%‡ | 5,183 | [188] |

| 2019-04-28 | 1,373 | 66 | 176 | 1,615 | 930 | 65%‡ | 11,841 | [189] |

| 2019-05-05 | 1,488 | 66 | 205 | 1,759 | 1,028 | 66%‡ | 12,969 | [190] |

| 2019-05-12 | 1,592 | 88 | 534 | 2,214 | 1,117 | 67%‡ | 13,174 | [191] |

| 2019-05-19 | 1,728 | 88 | 278 | 2,094 | 1,209 | 67%‡ | 12,608 | [192] |

| 2019-05-26 | 1,818 | 94 | 277 | 2,189 | 1,277 | 67%‡ | 20,415 | [193] |

| 2019-06-02 | 1,900 | 94 | 316 | 2,310 | 1,339 | 67%‡ | 19,465 | [194] |

| 2019-06-09 | 1,962 | 94 | 271 | 2,327 | 1,384 | 67%‡ | 15,045 | [195] |

| 2019-06-16 DRC & Uganda | 2,051 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 319 / 1 | 2,468 | 1,440 | 67%‡ /100%‡ | 15,992 / 90 | [196](see note 1) |

| 2019-06-23 | 2,145 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 276 / 0 | 2,515 | 1,506 | 67%‡ /100%‡ | 15,903 / 110 | [197][5] |

| 2019-06-30 | 2,231 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 309 / 0 | 2,634 | 1,563 | 67%‡ /100%‡ | 18,088 / 108 | [198][199] |

| 2019-07-07 | 2,314 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 323 / 0 | 2,731 | 1,625 | 68%‡ /100%‡ | 19,227 / 0 | [200][201] |

| 2019-07-14 | 2,407 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 335 / 0 | 2,836 | 1,665 | 67%‡ /100%‡ | 19,118 / 0 | [202][201] |

| 2019-07-21 | 2,484 / 3 | 94 / 0 | 361 / 0 | 2,939 | 1,737 | 67%‡ /100%‡ | 20,505 / 19 | [203][204] |

| 2019-07-28 DRC | 2,565 | 94 | 358 | 3,017 | 1,782 | 67%‡ | 20,072 | [205] |

| 2019-08-04 | 2,659 | 94 | 397 | 3,150 | 1,843 | 67%‡ | 19,156 | [206] |

| 2019-08-11 | 2,722 | 94 | 326 | 3,142 | 1,888 | 67%‡ | 15,988 | [207] |

| 2019-08-19 | 2,783 | 94 | 387 | 3,264 | 1,934 | 67%‡ | 15,817 | [208] |

| 2019-08-25 | 2,863 | 105 | 396 | 3,364 | 1,986 | 67%‡ | 17,293 | [209] |

| 2019-09-01 | 2,926 | 105 | 365 | 3,396 | 2,031 | 67%‡ | 16,370 | [210] |

| 2019-09-08 | 2,968 | 111 | 403 | 3,486 | 2,064 | 67%‡ | 14,737 | [211] |

| 2019-09-15 | 3,005 | 111 | 497 | 3,613 | 2,090 | 67%‡ | 13,294 | [32] |

| 2019-09-22 | 3,053 | 111 | 415 | 3,583 | 2,115 | 67%‡ | 11,335 | [212] |

| 2019-09-29 | 3,074 | 114 | 426 | 3,618 | 2,133 | 67%‡ | 7,775 | [213] |

| 2019-10-06 | 3,090 | 114 | 414 | 3,622 | 2,146 | 67%‡ | 7,807 | [214] |

| 2019-10-13 | 3,104 | 114 | 429 | 3,647 | 2,150 | 67%‡ | 5,622 | [215] |

| 2019-10-20 | 3,123 | 116 | 420 | 3,659 | 2,169 | 67%‡ | 5,570 | [216] |

| 2019-10-28 | 3,146 | 117 | 357 | 3,624 | 2,180 | 67%‡ | 4,437 | [217] |

| 2019-11-03 | 3,157 | 117 | 513 | 3,787 | 2,185 | 67%‡ | 6,078 | [36] |

| 2019-11-10 | 3,169 | 118 | 482 | 3,769 | 2,193 | 67%‡ | 6,137 | [218] |

| 2019-11-17 | 3,174 | 118 | 422 | 3,714 | 2,195 | 67%‡ | 4,857 | [219] |

| 2019-11-24 | 3,183 | 118 | 349 | 3,650 | 2,198 | 67%‡ | 3,371 | [220] |

| 2019-12-08 | 3,202 | 118 | 391 | 3,711 | 2,209 | 67%‡ | 2,955 | [221] |

|

# These figures may increase when new cases are discovered, and fall consequently, when tests show cases were not Ebola-related. | ||||||||

Containment and military conflict

.jpg)

The area in question, North Kivu, is in the middle of the Kivu Conflict, a military conflict with thousands of displaced refugees.[222][223] The affected area has about one million uprooted people and shares borders with Rwanda and Uganda, with cross border movement because of trade activities. The humanitarian crisis and deterioration of the security situation is expected to affect any response to the outbreak.[224][225]

There are about 70 armed military groups, among them the Alliance of Patriots for a Free and Sovereign Congo and the Mai-Mayi Nduma défense du Congo-Rénové, in North Kivu. The armed fighting has displaced thousands of individuals.[226] According to WHO, health care workers are to be accompanied by military personnel for protection and ring vaccination may not be possible.[227] On 11 August 2018, it was reported that seven individuals were killed in Mayi-Moya due to a military group, about 24 miles from the city of Beni where there were several EVD cases.[228][229][230]

On 24 August, it was reported that an Ebola-stricken physician had been in contact with some 97 individuals in an inaccessible military area, hence those 97 contacts could not be diagnosed.[231][232] In September, it was reported that 2 peacekeepers were attacked and wounded by rebel groups in Beni,[233] and 14 individuals were killed in a military attack.[234] In September 2018, the WHO's Deputy Director-General for Emergency Preparedness and Response described the combination of military conflict and civilian distress as a potential "perfect storm" that could lead to a rapid worsening of the outbreak.[21][22]

On 20 October, an armed rebel group in the DRC killed some 13 civilians and took 12 children as hostages. This attack occurred in Beni, the epicenter of the outbreak.[235][236] On 11 November, six people were killed in an attack by an armed rebel group in Beni; as a consequence vaccinations were suspended there.[237][238] In November 2018, a paper by the U.S. Center for Strategic and International Studies on the violence and the EVD outbreak indicated the situation might worsen depending on the result and response of presidential elections in the country in 2018.[239] Yet another attack reported on 17 November, in Beni by an armed rebel group forced the cessation of EVD containment efforts and WHO staff to evacuate to another DRC city for the time being.[240] Beni continues to be the site of attacks by militant groups as 18 civilians were killed on 6 December.[241] On 22 December it was reported that elections for the President of the DRC would go forward despite the EVD outbreak, including in the Ebola-stricken area of Beni.[242] Four days later, on 26 December, the DRC government reversed itself to indicate those Ebola-stricken areas, such as Beni, would not vote for several months;[243] as a consequence election protesters ransacked an Ebola assessment center in Beni just 24 hours later.[244][245][246] Post election tensions continued when it was reported that the DRC government had cut-off internet connections for the population, as the vote results were yet to be released.[247]

On 29 December, Oxfam said it would suspend its work due to the ongoing violence in the DRC;[248] on the same day, the International Rescue Committee suspended their Ebola support efforts as well.[249] On 18 January, the African Union indicated that presidential election results announcements should be suspended in the DRC, and have furthermore decided not to travel to the DRC.[250]

On 12 June 2019, in Uganda, a 5-year-old boy became the first cross-border victim of Ebola, with two more people testing positive for Ebola.[251] This shows the spread of Ebola to neighboring countries because of rebel attacks and community resistance hampering virus containment work in eastern Congo.[251]

Virology

The DRC Ministry of Public Health confirmed that the new Ebola outbreak is caused by the Zaire ebolavirus species. This is the same strain that was involved in the early 2018 outbreak in western DRC.[252]

Zaire ebolavirus strain is the most lethal of the six known strains (including the newly discovered Bombali strain);[253] it is fatal in up to 90% of cases.[254] Both Ebola and Marburg virus are part of the Filoviridae family.[255]

The filovirus genome contains seven genes, including VP40.[256] The natural reservoir of the virus is thought to be the African fruit bat,[257] which is used in many parts of Africa as bushmeat.[258]

Viral mechanism

A significant part of the actual EVD infection is based on immune suppression. When an individual is infected the pathophysiological process indicates that as systemic inflammation sets in there are coagulation problems, as well as vascular and the aforementioned immune system issues.[260]

Transmission

Ebola virus disease is found in a variety of bodily fluids in the human body such as breast milk, saliva, stool, blood, and semen. Due to this, the Ebola virus is an extremely infectious and contagious disease as a result of the easy contact with any of these bodily fluids. Although a few transmission methods are known, there is a possibility that many other methods are unknown and must be further researched. Here are some potential routes of transmission:[261][262]

- Droplets: Droplet transmission is when contact is made with virus-containing droplets that were unable to evaporate or move around.

- Fomites: Occurs when an individual comes in contact with a surface that a pathogen remains on and infects.

- Bodily fluids: The most common way of transmitting the Ebola virus in humans is through the contact with infected bodily fluids. Initially, the usage of unsterilized needles in a hospital was connected to the first outbreak of Ebola virus in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Containment

Contact tracing

Contact tracing is a way of identifying those who have been in direct contact with an infected individual and are thus at higher risk of becoming infected or infecting others. Such individuals are monitored for up to 21 days in the case of EVD.[263][264]

Burials

The IFRC has called funerals "super-spreading events" as burial traditions include kissing and generally touching bodies. Safe burial teams formed by healthworkers are subject to suspicion.[265]

Travel restrictions and border closings

On 26 July, it was reported that the country of Saudi Arabia would not allow visas from the DRC after the WHO declared it an international emergency due to EVD.[266] On 1 August, the country of Rwanda closed its border with the DRC, due to multiple cases in the city of Goma which borders the country in the upper Northwestern region.[267]

Treatment

In August 2018, the WHO evaluated the benefits and risks of drug treatment for EVD: Remdesivir, ZMapp, REGN3470-3471-3479, mAb114 and favipiravir.[268] The drug mAb114 (which is a monoclonal antibody) is being used for the first time to treat infected individuals during this EVD outbreak.[269]

In November 2018, the DRC gave approval to start clinical trials for EVD treatment. Medical authorities will not choose which of four experimental treatments will be given to an individual; instead it will be randomized.[270]

On 12 August 2019, it was announced that two clinical trial medications were found to improve the rate of survival in those infected by EVD. They are REGN-EB3, a cocktail of three monoclonal Ebola antibodies, and mAb114. These two will be further used in therapy; when used shortly after infection they were found to have a 90% survival rate. ZMapp and Remdesifir have been discontinued.[271][272][273][274]

Vaccination

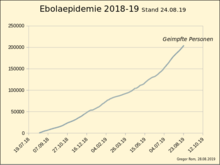

On 8 August 2018, the process of vaccination began with rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine.[276] While several studies have shown the vaccine to be safe and protective against the virus, additional research is needed before it can be licensed. Consequently, the WHO reports that it is being used under a ring vaccination strategy with what is known as "compassionate use" to protect persons at highest risk of the Ebola outbreak, i.e. contacts of those infected, contacts of those contacts, and front-line medical personnel.[277] As of 15 September, according to the WHO, almost a quarter of a million individuals have been vaccinated in this current outbreak.[32] Additionally on the same date the FDA set a target action date for March 14, 2020, for Merck's vaccine; should it be approved it would be the first licensed Ebola vaccine.[278]

On 20 September it was reported that a second vaccine by Johnson & Johnson would be introduced in the current EVD epidemic in the DRC.[279]

On November 2019, the World Health Organization prequalified an Ebola vaccine, Ervebo, for the first time against EVD.[280]

Pregnant and lactating women

Based on a lack of evidence about the safety of the vaccine during pregnancy, the DRC ministry of health and the WHO decided to not vaccinate women who are pregnant or lactating. This decision has been criticized as "utterly indefensible" from an ethical perspective by some authorities. They note that as caregivers of the sick, pregnant and lactating women are more likely to contract Ebola. They also note that since it is known that almost 100% of pregnant women who contract Ebola will die, a safety concern should not be a deciding factor.[281] As of June 2019, pregnant and lactating women were also being vaccinated.[282]

Vaccine stockpile

The DRC Ministry of Public Health reported on 16 August 2018 that 316 individuals had been vaccinated.[283] On 24 August, the DRC indicated it had vaccinated 2,957 individuals, including 1,422 in Mabalako against the Ebola virus.[284] By late October, more than 20,000 individuals had been vaccinated.[285] In December, Dr. Peter Salama, who is Deputy Director-General of Emergency Preparedness and Response for WHO, reported that the current 300,000 vaccine stockpile may not be enough to contain this EVD outbreak; additionally it takes several months to make more of the Zaire EVD vaccine (rVSV-ZEBOV).[286][287] On 11 December, it was reported that the stock of vaccine in Beni was 4,290 doses.[160]

As of August 2019, Merck & Co, the producers of the vaccine in use, reported a stockpile sufficient for 500,000 individuals, with more in production.[288]

Effectiveness

In April 2019, the WHO published the preliminary results of its research, in association with the DRC's Institut National pour la Recherche Biomedicale, into the effectiveness of the ring vaccination program, including data from 93,965 at-risk people who had been vaccinated. WHO stated that the rVSV-ZEBOV-GP vaccine had been 97.5% effective at stopping Ebola transmission, relative to no vaccination.[289][290] The vaccine had also reduced mortality among those who were infected after vaccination. The ring vaccination strategy was effective at reducing EVD in contacts of contacts (tertiary cases), with only two such cases being reported.[290]

Treatment centres

In August 2018, it was reported that the Mangina Ebola Treatment Center was operational.[291][292] A fourth Ebola Treatment Center (after those in Mangina, Beni and Butembo) was inaugurated in September in Makeke in the Mandima Health Zone of Ituri Province.[293] Makeke is less than five kilometers from Mangina along a well-traveled local road; the site had been proposed in August when it appeared that a second Ebola Treatment Center would be needed in the area, and space was insufficient in Mangina itself to accommodate one.[294] By mid-September, however, there had been only two additional cases in the Mandima Health Zone, and only sporadic cases were being reported in the Mabalako Health Zone.[295]

In February 2019, it was reported that attacks at treatment centers had been carried out in Butembo and Katwa. The motives behind the attacks were unclear. Due to the violence, international aid organizations had to stop their work in the two communities.[296][297] In April, an epidemiologist from WHO was killed and two health workers injured in a militia attack on Butembo University Hospital in Katwa.[298] In May, WHO's health emergencies chief said insecurity had become a "major impediment" to controlling the outbreak. He reports that since January there have been 42 attacks on health facilities and 85 health workers have been wounded or killed. "Every time we have managed to regain control over the virus and contain its spread, we have suffered major, major security events. We are anticipating a scenario of continued intense transmission."[23]

Healthcare workers

Health workers must don personal protection equipment during treatment of those affected by the virus, as well as various other tasks.[299] On 3 September, WHO stated that 16 health workers had contracted the virus.[130] On 10 December, the WHO reported that the current DRC outbreak had affected 49 healthcare workers as confirmed cases, and 15 had died.[159] As of 30 April 2019, there have been 92 health care workers in the DRC infected with EVD, of which 33 have died.[300]

On 5 October 2018, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Denis Mukwege, who tends to the female victims of the ongoing internal armed conflict in the DRC.[301]

Prognosis

In terms of prognosis, aside from the possible effects of post-Ebola syndrome,[302] there is also the reality of survivors returning to communities where they might be shunned due to the fear many have in the respective areas of the Ebola virus,[303][304] hence psychosocial assistance is needed.[305] Per the world Health Organization the current outbreak of EVD has left about 1,000 survivors.[306]

Post-Ebola syndrome signs and symptoms in an individual may include, but are not limited to the following:[307][308]

History

The Ebola virus disease outbreak in Zaire (Yambuku) started in late 1976, and was the second outbreak ever after the earlier one in Sudan the same year.[309][310] On 1 August 2018, the tenth Ebola outbreak was declared in the DRC, only a few days after the prior outbreak in the same country had been declared over on 24 July.[40][41]

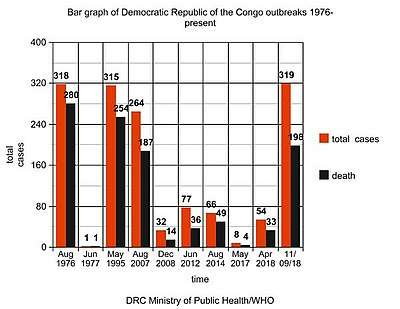

WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus indicated on 15 August, that the current outbreak in DRC may be worse than the West Africa outbreak of 2013–2016,[311] due to several factors.[312] The table below indicates the ten outbreaks that have occurred in the DRC since 1976:

- Table 2.

V・T Date | Country | Major location | Outbreak information | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Cases | Deaths | CFR | ||||

| Aug 1976 | Zaire | Yambuku | EBOV | 318 | 280 | 88% | [313] |

| Jun 1977 | Zaire | Tandala | EBOV | 1 | 1 | 100% | [314][315] |

| May–Jul 1995 | Zaire | Kikwit | EBOV | 315 | 254 | 81% | [316] |

| Aug–Nov 2007 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kasai-Occidental | EBOV | 264 | 187 | 71% | [317] |

| Dec 2008–Feb 2009 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kasai-Occidental | EBOV | 32 | 14 | 45% | [318] |

| Jun–Nov 2012 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Orientale | BDBV | 77 | 36 | 47% | [314] |

| Aug–Nov 2014 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Tshuapa | EBOV | 66 | 49 | 74% | [319] |

| May–Jul 2017 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Likati | EBOV | 8 | 4 | 50% | [320] |

| Apr–Jul 2018 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Bikoro | EBOV | 54 | 33 | 61% | [321] |

| Aug 2018–present | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kivu | EBOV | 3,718 | 2,195 | ongoing | [322] |

This map shows previous EVD outbreaks in the area of central Africa, which includes the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This outbreak is the biggest of the ten recorded outbreaks that have occurred in the DRC.[323]

Learning from other responses, such as during the 2000 outbreak in Uganda, the WHO established its Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network, and other public health measures were instituted in areas at high risk. Field laboratories were established to confirm cases, instead of shipping samples to South Africa.[324] Additionally, outbreaks are also closely monitored by the CDC Special Pathogens Branch.[325]

Outlook

Projected cases

Until the outbreak in North Kivu in 2018, no outbreak had surpassed 320 total cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. As of 24 February 2019, the outbreak has surpassed 1,000 total cases (1,048) and has yet to be brought under control.[330][314]

On 10 May, the U.S. Centers for Disease control and Prevention indicated that the outbreak could well surpass the West Africa epidemic given time.[331]

The 12 May issue of WHO Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks and Other Emergencies, indicates that "continued increase in the number of new EVD cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is worrying...no end in sight to the difficult security situation".[191]

Statistical measures

One way to measure the outbreak is the basic reproduction number, R0, a statistical measure of the average number of people expected to be infected by one person who has a disease. If the rate is less than 1, the infection dies out; if it is greater than 1, the infection continues to spread—with exponential growth in the number of cases.[332] A March 2019, paper by Tariq et al. indicated (rho = −0.37, p < 0.001) oscillating around 0.9 for mean R.[333]

Response

During the Ebola outbreak in Democratic Republic of the Congo, a number of organizations have come forward to help in different capacities: CARITAS DRC, CARE International, Cooperazione Internationale (COOPE), Catholic Organization for Relief and Development Aid (CORDAID/PAP-DRC), International Rescue Committee (IRC), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Oxfam, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and Samaritan's Purse.[132]

WHO

On 12 April 2019, the WHO Emergency Committee was reconvened by the WHO Director-General after an increase in the rate of new cases, and determined that the outbreak still failed to meet the criteria for a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[334][335]

Following the confirmation of Ebola crossing into Uganda, a third review by the WHO on 14 June 2019,[27] concluded that while the outbreak was a health emergency in the DRC and the region, it does not meet all the three criteria for a PHEIC.[28] Following a case in Goma, the reconvening of a fourth review was announced on 15 July 2019.[30] The WHO officially announced it as a PHEIC on 17 July 2019,[31] and as of 18 October 2019, it continues to be a PHEIC.[114]

International governments

Financial support has been contributed by the governments of the US and the UK, among others. The UK DfID minister, Rory Stewart, visited the area in July 2019, and called for other western countries, including Canada, France and Germany, to donate more financial aid. He identified a funding deficit of $100–300 million to continue responding to the outbreak until December, for example to pay for ring vaccination. He urged WHO to classify the situation as a PHEIC, to facilitate the release of international aid.[336][337]

See also

Notes

- ...in the Congolese statistics cases of Mabalako. Uganda's index case and 7 other family members were classified in Mabalako, the health zone where they started to develop symptoms. Of these 8 confirmed cases of the same family, 5 remained in the DRC and 3 had crossed the border. [...] The 2 deaths of Bwera are the 5-year-old boy and the 50-year-old grandmother who were classified...[7]

- Ituri province was added to N. Kivu province, in terms of viral infection, when the first case of EVD was confirmed on 13 August.[8]

References

- "Operations Dashboard for ArcGIS". who.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Gladstone, Rick (12 June 2019). "Two More Ebola Cases Diagnosed in Uganda as First Victim, 5, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- News, A. B. C. "2nd Ebola death in Uganda after outbreak crosses border". ABC News. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak Uganda Situation Reports" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "Update of Ebola Outbreak in Kasese District, 21 June 2019 – Uganda". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- "Congolese girl, 9, dies of Ebola in Uganda – hospital official". Reuters. 30 August 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Situation épidémiologique dans les provinces du Nord-Kivu et de l'Ituri" (in French). Dr. Oly Ilunga Kalenga, Ministre de la Santé. 13 June 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans la province du Nord Kivu au Lundi 13 août 2018". mailchi.mp (in French). Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Congo declares new Ebola outbreak in eastern province". Reuters. August 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- "Congo announces 4 new Ebola cases in North Kivu province". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- "Cluster of presumptive Ebola cases in North Kivu in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Hunt, Katie. "Ebola outbreak enters 'truly frightening phase' as it turns deadly in Uganda". CNN. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Vendredi 9 novembre 2018". mailchi.mp (in French). Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- "Current Ebola Outbreak Is Worst in Congo's History: Ministry". usnews.com. Us News and World report. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- Editorial, Reuters (15 October 2018). "Congo confirms 33 Ebola cases in past week, of whom 24 died". Reuters. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- "Ebola Virus Disease Distribution Map: Cases of Ebola Virus Disease in Africa Since 1976". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 May 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Operations Dashboard for ArcGIS". who.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- Weber, Lauren (29 November 2018). "The Ebola Outbreak In Congo Just Became The Second Largest Ever". Huffington Post. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- "2014–2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 29 March 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "World Digest: CONGO: Death toll tops 1,000 in Ebola outbreak". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- Belluz, Julia (25 September 2018). "An Ebola "perfect storm" is brewing in Democratic Republic of the Congo". Vox. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Ebola-hit DRC faces 'perfect storm' as uptick in violence halts WHO operation – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. 25 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "World Digest: CONGO: Death toll tops 1,000 in Ebola outbreak". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Spinney, Laura (17 January 2019). "In Congo, fighting a virus and a groundswell of fake news". Science. 363 (6424): 213–214. Bibcode:2019Sci...363..213S. doi:10.1126/science.363.6424.213. PMID 30655420.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- "UN calls for end to Congo fighting to combat Ebola outbreak". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- Gladstone, Rick (12 June 2019). "Boy, 5, and Grandmother Die in Uganda as More Ebola Cases Emerge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 14 June 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "High-level meeting on the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo affirms support for Government-led response and UN system-wide approach". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- Schnirring, Lisa; 2019 (15 July 2019). "Ebola spread to Goma triggers new emergency talks, cases top 2,500". CIDRAP. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- Goldberg, Mark Leon (17 July 2019). "The World Health Organization Just Declared an Ebola "Emergency" in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Here's What That Means". UN Dispatch. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 37: 9 - 15 September 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Soucheray, Stephanie (10 October 2019). "WHO: Ebola outbreak back to where it began". CIDRAP News. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- MacIntyre, C. Raina; Chughtai, Abrar Ahmad (1975). "Recurrence and reinfection--a new paradigm for the management of Ebola virus disease". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 43 (4): 58–61. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2015.12.011. ISSN 1878-3511. PMID 2.

- "Exclusive: WHO, Congo eye tighter rules for Ebola care over immunity concerns". Reuters. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 44: 28 October - 3 November 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Mwanamilongo, Saleh. "Congo announces 4 new Ebola cases in North Kivu province". Associated Press. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- "The Democratic Republic of the Congo: Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak – Epidemiological Situation DG ECHO Daily Map | 3 August 2018". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Dyer, Owen (2018). "Ebola: new outbreak appears in Congo a week after epidemic was declared over". The BMJ. 362: k3421. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3421. PMID 30087112. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Media Advisory: Expected end of Ebola outbreak". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- Weber, Lauren (1 August 2018). "New Ebola Outbreak Confirmed In Democratic Republic Of Congo". Huffington Post. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- "UNICEF DR Congo (North Kivu) Ebola Situation Report #1 – 3 August 2018". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans la province du Nord Kivu au Mercredi 5 septembre 2018 (ERRATUM)". mailchi.mp (in French). Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "DRC: MSF treats 65 people with Ebola in first month of intervention in North Kivu". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "Oxfam responds to the new Ebola Outbreak in Beni, North Kivu, DRC". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Samedi 10 novembre 2018". mailchi.mp (in French). Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Dimanche 23 décembre 2018". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- "World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations". population.un.org. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans la province du Nord Kivu au Mardi 7 août 2018". us13.campaign-archive.com. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- "Ebola: Health ministry issues alert". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans la province du Nord Kivu au Jeudi 9 août 2018". mailchi.mp (in French). Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "UK response to the Ebola outbreak in North Kivu, DRC". GOV.UK. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- Editorial, Reuters (17 August 2018). "WHO expects more Ebola cases in Congo, can't reach no-go areas". Reuters. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 33: 11 – 17 August 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Gulland, Anne (6 September 2018). "Ebola death in city of one million prompts fears of urban spread". The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "Rebel attack halts DR Congo Ebola work". BBC News Online. 24 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- Schlein, Lisa. "WHO Warns Ebola Spreading in Eastern DR Congo". VOA. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

A perfect storm of active conflict limiting our ability to access civilians, distress by segments of the community already traumatized by decades of conflict and of murder, driven by a fear of a terrifying disease

- "Ebola in Democratic Republic of the Congo". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 43: 20 – 26 October 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Vinck, Patrick; Pham, Phuong N; Bindu, Kenedy K; et al. (March 2019). "Institutional trust and misinformation in the response to the 2018–19 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu, DR Congo: a population-based survey". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 19 (5): 529–536. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30063-5. PMID 30928435.

- "CDC director warns that Congo's Ebola outbreak may not be containable". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- "Congo's Ebola outbreak to last at least 6 more months". CNBC. 13 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "Congo's Ebola outbreak almost second highest ever". Axios. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- "Congo's Worst Ebola Outbreak Hits Women Especially Hard – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Samedi 29 décembre 2018". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Mardi 22 janvier 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- Grady, Denise (16 March 2019). "Ebola Epidemic in Congo Could Last Another Year, C.D.C. Director Warns". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 13: 25 – 31 March 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "1 in 4 people near Congo's Ebola outbreak believe virus isn't real, new study says". ABC News. 29 March 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Aid agencies evacuate DR Congo Ebola and measles hotspots as violence flares - Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Grady, Denise (15 July 2019). "Ebola Outbreak Reaches Major City in Congo, Renewing Calls for Emergency Order". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Congo confirms 1st Ebola case in city of Goma". KPIC. Associated Press. 14 July 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- "First Ebola case in Congo city of Goma detected". Reuters. 14 July 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- "Congo confirms first Ebola case in city of Goma". STAT. 14 July 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- "Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 17 July 2019" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Soucheray, Stephanie; 2019 (16 July 2019). "WHO will take up Ebola emergency declaration question for a fourth time". CIDRAP. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "New Ebola case diagnosed in DR Congo's Goma: health official". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Second Ebola death in densely packed DR Congo city". BBC. 31 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- "Roundup: Rwandan hospitals conduct Ebola simulation drills to prevent outbreak – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "DR Congo Ebola epidemic spreads as second Goma patient dies, third case is confirmed". France 24. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 56 - Democratic Republic of the Congo".

- Beaumont, Peter (16 August 2019). "Congo Ebola outbreak spreads to new province as epidemic continues to spiral". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Ebola virus outbreak spreads, claiming first victims in a new region of Congo". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Fourth Ebola case reported in DRC's South Kivu province".

- Schlein, Lisa. "UN Stepping Up Ebola Screening of Refugees Fleeing DR Congo". VOA. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Uganda opens Ebola treatment units at border with DRC – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Uganda opens Ebola treatment units at border with DRC". Premium Times Nigeria. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease – Republic of Uganda". World Health Organization (WHO). 13 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "Uganda: Ebola Preparedness Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) – DREF Operation n° MDRUG041". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- "Uganda prepares to vaccinate against Ebola in case the virus strikes the country – Uganda". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "WHO Setting Up Ebola Vaccination Strategy In Uganda After Outbreak In DRC". article.worldnews.com. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Congo confirms Ebola case at Ugandan border". Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Editorial, Reuters (21 September 2018). "Congo confirms Ebola case at Ugandan border". Reuters. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Athumani, Halima. "Uganda to Deploy Ebola Vaccine to Health Workers on DRC Border". VOA. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Kalenga, Oly Ilunga; Moeti, Matshidiso; Sparrow, Annie; Nguyen, Vinh-Kim; Lucey, Daniel; Ghebreyesus, Tedros A. (29 May 2019). "The Ongoing Ebola Epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2018–2019". New England Journal of Medicine. 381 (4): 373–383. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1904253. PMID 31141654.

- "Flood of refugees fleeing Congo raises fears of spreading Ebola". www.cbsnews.com. 2 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Uganda quarantines 13 people who contacted dead body of suspected Ebola case – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Results of suspected Ebola case in Uganda turn negative: health official – Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Winsor, Morgan (12 June 2019). "Ebola-stricken boy who became 1st cross-border case in growing outbreak dies". ABC News. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Ugandan medics now tackling Ebola say they lack supplies". Star Tribune. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- "Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak Uganda Situation Reports" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- News, A. B. C. (7 December 2018). "2nd deadliest Ebola outbreak in history spreads to major city". ABC News. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Ebola outbreak puts DR Congo's neighbors on high alert | DW | 15.06.2019". DW.COM.

- "Congo Ebola victim may have entered Rwanda and Uganda, says WHO". Reuters. 18 July 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Press Release | Ministry of Health". health.go.ug. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Uganda says a traveling Congolese girl has Ebola". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "WHO | Cases of Undiagnosed Febrile Illness – United Republic of Tanzania". WHO. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "WHO accuses Tanzania of withholding information about suspected Ebola cases". Washington Post. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "Tanzania not sharing information on suspected Ebola cases: WHO". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "U.S. alerts travelers to Tanzania about possible unreported Ebola". STAT. 27 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "Health - Tanzania travel advice". GOV.UK. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- "Tanzania provides Ebola preparedness updates to WHO". newsghana.com. 24 October 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "WHO | Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 18 October 2019". WHO. 18 October 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Diamond, Dan. "Doctor exposed to Ebola brought to United States". POLITICO. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Doctor possibly exposed to Ebola being monitored in Nebraska". Washington Examiner. 29 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "American monitored for possible Ebola did not have disease, released". NBC News. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "WHO | World Health Organization". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Communication spéciale du Ministre de la Santé en rapport à la situation épidémiologique dans la Province du Nord-Kivu". mailchi.mp (in French). Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- "WHO AFRO Outbreaks and Other Emergencies, Week 31: 28 July – 3 August (Data as reported by 17:00; 3 August 2018)". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans la province du Nord Kivu au Samedi 4 août 2018". mailchi.mp (in French). Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 1". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- News, ABC. "Congo's health ministry confirms 3 more cases of Ebola". ABC News. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 32: 04 – 10 August 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 2". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 3". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "WHO AFRO Outbreaks and Other Emergencies, Week 34: 18 – 24 August (Data as reported by 17:00; 24 August 2018)". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 4". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 35: 25 – 31 August 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 5". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 36: 1 – 7 September 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 6". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo: Disease outbreak news – 7 September 2018". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 37: 8 – 14 September 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 7 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- "DR Congo – 2018 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu Province (September 17, 2018 update) – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 38: 15 – 21 September 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 8 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 39: 22 – 28 September 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 9 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 40: 29 September – 05 October 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 10 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 41: 06 – 12 October 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 11 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 42: 13 – 19 October 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 12 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 13 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 44: 27 October – 02 November 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 14 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 45: 03 – 09 November 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 15 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 46: 10 – 16 November 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 16 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 47: 17 – 23 November 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 17 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 48: 24 – 30 November 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 18 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 49: 01 – 07 December 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease – External Situation Report 19 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 50: 08 – 14 December 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 51: 15 – 21 December 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 52: 22 – 28 December 2018". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 01: 29 December 2018 – 04 January 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 02: 05 – 11 January 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 03: 12 – 18 January 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Vendredi 18 janvier 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 21 January 2019. WHO did not report suspected cases, added same day reference from DRC Ministry of Public Health

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 04: 19 – 25 January 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Vendredi 25 janvier 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 05: 26 January – 01 February 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Vendredi 1 février 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 06: 04 – 10 February 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Dimanche 10 février 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 07: 11 – 17 February 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Dimanche 17 février 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 08: 18 – 24 February 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Samedi 23 février 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 09: 25 February – 03 March 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Dimanche 3 mars 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 10: 04 – 10 March 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Dimanche 10 mars 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 11: 11 – 17 March 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Dimanche 17 mars 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 12: 18 – 24 March 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Lundi 25 mars 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Dimanche 31 mars 2019". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 14: 01 – 07 April 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 15: 08 – 14 April 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 16: 15 – 21 April 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 17: 22 – 28 April 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 18: 29 April – 5 May 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 19: 6 May – 12 May 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 20: 13 – 19 May 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 21: 20 – 26 May 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 22: 27 May – 02 June 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 23: 03 – 09 June 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 24: 10 – 16 June 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 25: 17 – 23 June 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 26: 24 – 30 June 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "Uganda's groundwork in preparedness bodes well for stopping Ebola's spread within its borders". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "Weekly bulletins on outbreaks and other emergencies". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Joint advisory on Ebola virus disease in Uganda – Uganda". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "WHO AFRO Outbreaks and Other Emergencies, Week 28: 8 – 14 July 2019; Data as reported by 17:00; 14 July 2019 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 29: 15 – 21 July 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "WHO reports new Ebola incident near Uganda-DRC border". The East African. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "WHO AFRO Outbreaks and Other Emergencies, Week 30: 22 – 28 July 2019; Data as reported by 17:00; 28 July 2019 – Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 31: 29 July – 04 August 2019". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 32: 05 – 11 August 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 33: 12 – 18 August 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 34: 19 – 25 August 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 35: 26 August – 01 September 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 36: 2 - 8 September 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 38: 16 - 22 September 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 39: 23 - 29 September 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 40: 30 September - 6 October 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 41: 7 - 13 October 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 42: 14 - 20 October 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 43: 21 - 27 October 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Outbreaks and Emergencies Bulletin, Week 45: 4 - 10 November 2019". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Weekly bulletins on outbreaks and other emergencies". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Weekly bulletins on outbreaks and other emergencies". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "Weekly bulletins on outbreaks and other emergencies". WHO | Regional Office for Africa. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Ebola In A Conflict Zone". NPR.org. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Congo Ebola outbreak compounds already dire humanitarian crisis". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo: Disease outbreak news, 4 August 2018". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- "Conflict in new Ebola zone of DR Congo exacerbates complexity of response: WHO emergency response chief". UN News. 3 August 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- "Atrocity Alert, No. 116, 1 August 2018". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "Out of the frying pan, into the fire with a new Ebola outbreak in Congo". Science | AAAS. 6 August 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "Congo's latest Ebola outbreak taking place in a war zone". thestate. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Vaccinations underway in Congo's latest Ebola outbreak | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "WHO calls for free and secure access in responding to Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- "DRC: Doctor stricken with Ebola in rebel stronghold". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- Burke, Jason (24 August 2018). "Ebola: medics brace for new cases as DRC outbreak spreads". the Guardian. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- Editorial, Reuters (4 September 2018). "Rebels ambush South African peacekeepers in Congo Ebola zone". Reuters. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Rebel Attack in Congo Ebola Zone Kills at Least 14 Civilians". VOA. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- "Congo rebels kill 13, abduct children at Ebola treatment center". New York Post. 21 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- "Congo Rebels Kill 15, Abduct Kids in Ebola Outbreak Region". VOA. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- "Rebels kill six, kidnap five in east DRC". News24. 12 November 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Lundi 12 novembre 2018". mailchi.mp (in French). Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- "North Kivu's Ebola Outbreak at Day 90: What Is to Be Done?". www.csis.org. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Anti-Ebola efforts suspended amid violence". BBC News. 17 November 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "Militants kill at least 18 civilians in Congo's Ebola zone". Reuters. 7 December 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "Voting will take place in DR Congo's Ebola-hit region: official | DR Congo News | Al Jazeera". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- Mwanamilongo, Saleh; Boussion, Mathilde (26 December 2018). "Congo delays Sunday's election for months in Ebola zone". AP NEWS. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "Protesters attack DR Congo Ebola centre". BBC News. 27 December 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC – Evolution de la riposte contre l'épidémie d'Ebola dans les provinces du Nord Kivu et de l'Ituri au Jeudi 27 décembre 2018". us13.campaign-archive.com (in French). Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "Statement on disruptions to the Ebola response in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved 28 December 2018.