Henipavirus

Henipavirus is a genus of RNA viruses in the family Paramyxoviridae, order Mononegavirales containing five established species.[1][2] Henipaviruses are naturally harboured by pteropid fruit bats (flying foxes) and microbats of several species.[3] Henipaviruses are characterised by long genomes and a wide host range. Their recent emergence as zoonotic pathogens capable of causing illness and death in domestic animals and humans is a cause of concern.[4][5]

| Henipavirus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Colored transmission electron micrograph of a Hendra henipavirus virion (ca. 300 nm length) | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Paramyxoviridae |

| Subfamily: | Orthoparamyxovirinae |

| Genus: | Henipavirus |

| Type species | |

| Hendra henipavirus | |

| Species | |

| |

In 2009, RNA sequences of three novel viruses in phylogenetic relationship to known henipaviruses were detected in African straw-colored fruit bats (Eidolon helvum) in Ghana. The finding of these novel henipaviruses outside Australia and Asia indicates that the region of potential endemicity of henipaviruses may be worldwide.[6] These African henipaviruses are slowly being characterised.[7]

Taxonomy

| Genus | Species | Virus (Abbreviation) |

| Henipavirus | Cedar henipavirus | Cedar virus (CedV) |

| Ghanaian bat henipavirus | Kumasi virus (KV) | |

| Hendra henipavirus* | Hendra virus (HeV) | |

| Mòjiāng virus (MojV) | ||

| Nipah henipavirus | Nipah virus (NiV) | |

| Table legend: "*" denotes type species. | ||

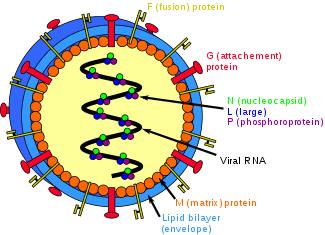

Virus structure

Henipavirions are pleomorphic (variably shaped), ranging in size from 40 to 600 nm in diameter.[9] They possess a lipid membrane overlying a shell of viral matrix protein. At the core is a single helical strand of genomic RNA tightly bound to N (nucleocapsid) protein and associated with the L (large) and P (phosphoprotein) proteins, which provide RNA polymerase activity during replication.

Embedded within the lipid membrane are spikes of F (fusion) protein trimers and G (attachment) protein tetramers. The function of the G protein is to attach the virus to the surface of a host cell via EFNB2, a highly conserved protein present in many mammals.[10][11][12] The structure of the attachment glycoprotein has been determined by X-ray crystallography.[13] The F protein fuses the viral membrane with the host cell membrane, releasing the virion contents into the cell. It also causes infected cells to fuse with neighbouring cells to form large, multinucleated syncytia.

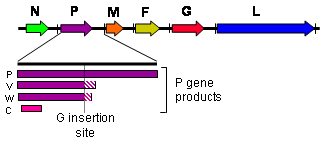

Genome structure

As all mononegaviral genomes, Hendra virus and Nipah virus genomes are non-segmented, single-stranded negative-sense RNA. Both genomes are 18.2 kb in length and contain six genes corresponding to six structural proteins.[14]

In common with other members of the Paramyxoviridae family, the number of nucleotides in the henipavirus genome is a multiple of six, consistent with what is known as the 'rule of six'.[15] Deviation from the rule of six, through mutation or incomplete genome synthesis, leads to inefficient viral replication, probably due to structural constraints imposed by the binding between the RNA and the N protein.

Henipaviruses employ an unusual process called RNA editing to generate multiple proteins from a single gene. The specific process in henipaviruses involves the insertion of extra guanosine residues into the P gene mRNA prior to translation. The number of residues added determines whether the P, V or W proteins are synthesised. The functions of the V and W proteins are unknown, but they may be involved in disrupting host antiviral mechanisms.

Hendra virus

Emergence

Hendra virus (originally called "Equine morbillivirus") was discovered in September 1994 when it caused the deaths of thirteen horses, and a trainer at a training complex at 10 Williams Avenue, Hendra, a suburb of Brisbane in Queensland, Australia.[16][17]

The index case, a mare called Drama Series, brought in from a paddock in Cannon Hill, was housed with 19 other horses after falling ill, and died two days later. Subsequently, all of the horses became ill, with 13 dying. The remaining six animals were subsequently euthanised as a way of preventing relapsing infection and possible further transmission.[18] The trainer, Victory ('Vic') Rail, and the stable foreman, Ray Unwin, were involved in nursing the index case, and both fell ill with an influenza-like illness within one week of the first horse’s death. The stable hand recovered but Rail died of respiratory and renal failure. The source of the virus was most likely frothy nasal discharge from the index case.[19]

A second outbreak occurred in August 1994 (chronologically preceding the first outbreak) in Mackay 1,000 km north of Brisbane resulting in the deaths of two horses and their owner.[20] The owner, Mark Preston, assisted in necropsies of the horses and within three weeks was admitted to hospital suffering from meningitis. Mr Preston recovered, but 14 months later developed neurologic signs and died. This outbreak was diagnosed retrospectively by the presence of Hendra virus in the brain of the patient.[21]

Transmission

Flying foxes have been identified as the reservoir host of Hendra Virus. A seroprevalence of 47% is found in the flying foxes, suggesting an endemic infection of the bat population throughout Australia.[22] Horses become infected with Hendra after exposure to bodily fluid from an infected flying fox. This often happens in the form of urine, feces, or masticated fruit covered in the flying fox's saliva when horses are allowed to graze below roosting sites. The seven human cases have all been infected only after contact with sick horses. As a result, veterinarians are particularly at risk for contracting the disease.

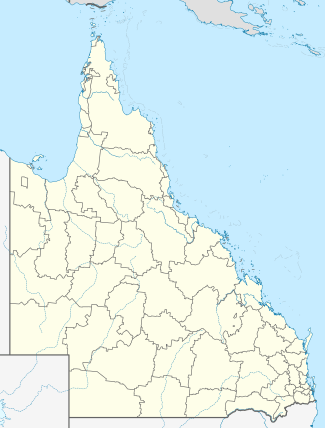

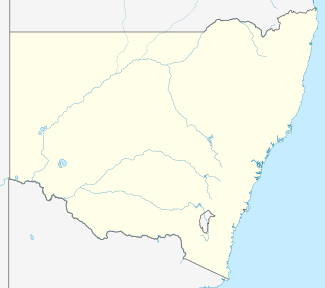

Australian outbreaks

As of June 2014, a total of fifty outbreaks of Hendra virus have occurred in Australia, all involving infection of horses. As a result of these events, eighty-three horses have died or been euthanised. A further four died or were euthanised as a result of possible hendra infection.

Case fatality rate in humans is 60% and in horses 75%.[23]

Four of these outbreaks have spread to humans as a result of direct contact with infected horses. On 26 July 2011 a dog living on the Mt Alford property was reported to have HeV antibodies, the first time an animal other than a flying fox, horse, or human has tested positive outside an experimental situation.[24]

These events have all been on the east coast of Australia, with the most northern event at Cairns, Queensland and the event furthest south at Kempsey, New South Wales. Until the event at Chinchilla, Queensland in July 2011, all outbreak sites had been within the distribution of at least two of the four mainland flying foxes (fruit bats); Little red flying fox, (Pteropus scapulatus), black flying fox, (Pteropus alecto), grey-headed flying fox, (Pteropus poliocephalus) and spectacled flying fox, (Pteropus conspicillatus). Chinchilla is considered to be only within the range of little red flying fox and is west of the Great Dividing Range. This is the furthest west the infection has ever been identified in horses.

The timing of incidents indicates a seasonal pattern of outbreaks. Initially this was thought to possibly related to the breeding cycle of the little red flying foxes. These species typically give birth between April and May.[25][26] Subsequently however, the Spectacled flying fox and the Black flying fox have been identified as the species more likely to be involved in infection spillovers.[27]

Timing of outbreaks also appears more likely during the cooler months when it is possible the temperature and humidity are more favourable to the longer term survival of the virus in the environment.[28]

There is no evidence of transmission to humans directly from bats, and, as such it appears that human infection only occurs via an intermediate host, a horse.[29] Despite this in 2014 the NSW Government approved the destruction of flying fox colonies.[30]

| List of Australian Hendra outbreaks | ||

|---|---|---|

| Date | Location | Details |

| August 1994 | Mackay, Queensland | Death of two horses and one person, Mark Preston.[20] |

| September 1994 | Hendra, Queensland | 20 horses died or were euthanised. Two people infected. One of them, Victory ("Vic") Rail, a nationally prominent trainer of racehorses, died.[16] |

| January 1999 | Trinity Beach, Cairns, Queensland | Death of one horse.[31] |

| October 2004 | Gordonvale, Cairns, Queensland | Death of one horse. A veterinarian involved in autopsy of the horse was infected with Hendra virus, and suffered a mild illness.[32] |

| December 2004 | Townsville, Queensland | Death of one horse.[32] |

| June 2006 | Peachester, Sunshine Coast, Queensland | Death of one horse.[32] |

| October 2006 | Murwillumbah, New South Wales | Death of one horse.[33] |

| July 2007 | Peachester, Sunshine Coast, Queensland | Infection of one horse (euthanised) |

| July 2007 | Clifton Beach, Cairns, Queensland | Infection of one horse (euthanised).[34] |

| July 2008 | Redlands, Queensland | Death of five horses; four died from the Henda virus, the remaining animal recovered but was euthanised because of a government policy that requires all animals with antibodies to be euthanised due to a potential threat to health. Two veterinary workers from the affected property were infected leading to the death of one, veterinary surgeon Ben Cuneen, on 20 August 2008.[35] The second veterinarian was hospitalized after pricking herself with a needle she had used to euthanize the horse that had recovered. A nurse exposed to the disease while assisting Cuneen in caring for the infected horses was also hospitalized.[36] The Biosecurity Queensland website indicates that 8 horses died during this event,[18] however a review of the event indicates that five horses are confirmed to have died from HeV and three of the horses "are regarded as improbable cases of Hendra virus infection...".[37] |

| July 2008 | Proserpine, Queensland | Death of four horses.[18] |

| July 2009 | Cawarral, Queensland | Death of four horses.[18] Queensland veterinary surgeon Alister Rodgers tested positive after treating the horses.[38] On 1 September 2009 after two weeks in a coma, he became the fourth person to die from exposure to the virus.[39] |

| September 2009 | Bowen, Queensland | Death of two horses.[18] |

| May 2010 | Tewantin, Queensland | Death of one horse.[40] |

| 20 June 2011 – 31 July 2011 | Mount Alford, Queensland | Death of three horses (all confirmed to have died of Hendra) and sero-conversion of a dog. The first horse death on this property occurred on 20 June 2011, although it was not until after the second death on 1 July 2011 that samples taken from the first animal were tested. The third horse was euthanised on 4 July 2011.[41][42][43] On 26 July 2011 a dog from this property was reported to have tested positive for HeV antibodies. Reports indicate that this Australian Kelpie, a family companion, will be euthanised in line with government policy. Biosecurity Queensland suggest the dog most likely was exposed to HeV though one of the sick horses.[44][45] Dusty was euthanised on 31 July 2011 following a second positive antibody test.[46] |

| 26 June 2011 | Kerry, Queensland | The horse was moved after it became sick to another property at Beaudesert, Queensland. Death of one horse.[47] |

| 28 June 2011 | Loganlea, Logan City, Queensland | Death of one horse. Unusually this horse had HeV antibodies present in its blood at the time of death. How this immune response should be interpreted is a matter of debate.[48][49] |

| 29 June 2011 | Mcleans Ridges, Wollongbar, New South Wales | Death of one horse.[50][51] The second horse on the property tested positive to Hendra and was euthanised on 12 July 2011.[52] |

| 3 July 2011 | Macksville, New South Wales | Death of one horse.[53][54] |

| 4 July 2011 | Park Ridge, Logan City, Queensland | Death of one horse.[55] |

| 11 July 2011 | Kuranda, Queensland | Death of one horse.[56] |

| 13 July 2011 | Hervey Bay, Queensland | Death of one horse.[57] |

| 14 July 2011 | Lismore, New South Wales | Death of one horse.[58] |

| 15 July 2011 | Boondall, Queensland | Death of one horse.[59] |

| 22 July 2011 | Chinchilla, Queensland | Death of one horse.[60] |

| 24 July 2011 | Mullumbimby, New South Wales | Death of one horse.[61] |

| 13 August 2011 | Mullumbimby, New South Wales | Death of one horse. A horse was found dead after being unwell the day before. HeV infection was confirmed on 17 August 2011.[62] |

| 15 August 2011 | Ballina, New South Wales | Death of one horse.[63] |

| 17 August 2011 | South Ballina, New South Wales | Death of two horses. The horses were found dead in a field. Both tested positive to HeV. The exact date of death is not known, but HeV infection was confirmed on 17 August 2011.[62] |

| 23 August 2011 | Currumbin Valley, Gold Coast, Queensland | Death of one horse.[64] |

| 28 August 2011 | North of Ballina, New South Wales | Death of one horse.[65] |

| 11 October 2011 | Beachmere, Caboolture Queensland | One horse euthanised after testing positive. A horse that died on the property one week before may have died of HeV.[66] On 15 October 2011 another horse on the property was euthanised following a positive HeV antibody test.[67] |

| 3 January 2012 | Townsville, Queensland | A horse that died or was euthanised on 3 January 2012 returned a positive HeV test on 5 January 2012.[68] |

| 26 May 2012 | Rockhampton, Queensland | One horse died.[69][70] |

| 28 May 2012 | Ingham, Queensland | One horse died.[69][70] A dog returned a positive test but was subsequently cleared.[71] |

| 19 July 2012 | Rockhampton, Queensland | One horse died. On 27 July it was announced that two other horses on the property, showing clinical signs of the disease, had been euthanised. Two dogs were assessed, and the property was quarantined.[72][73][74] |

| 27 June 2012 | Mackay, Queensland | One horse was euthanised after returning a positive HeV test. 15 horses on the property are being tested and quarantined, along with horses on neighbouring properties.[75] |

| 27 July 2012 | Cairns, Queensland | One horse died.[76] |

| 5 September 2012 | Port Douglas, Queensland | One horse died. The property with 13 other horses is quarantined.[77][78] |

| 1 November 2012 | Ingham, Queensland | One symptomatic horse euthanised. A test for HeV the following day proved positive. The property, with seven other horses, quarantined.[79][80] |

| 20 January 2013 | Mackay, Queensland | One horse died.[81] |

| 19 February 2013 | Atherton Tablelands, North Queensland | One horse died. Four horses and four people from the property were assessed.[82] |

| 3 June 2013 | Macksville, New South Wales | Death of one horse, a second horse vaccinated, five cats and a dog were monitored.[83] |

| 1 July 2013 | Tarampa, Queensland | One horse died. HeV virus confirmed.[84] |

| 4 July 2013 | Macksville, New South Wales | Six year old gelding died. Several other horses, dogs and cats were tested.[85][86] A dog from the property tested positive for HeV and was euthanised around 19 July 2013[87] |

| 5 July 2013 | Gold Coast, Queensland | One horse died. No other horses on property.[88] |

| 6 July 2013 | Kempsey, New South Wales | Eighteen-year-old unvaccinated mare died, other animals on property under observation.[89] |

| 9 July 2013 | Kempsey, New South Wales | Thirteen-year-old unvaccinated quarterhorse died, other animals on property were put under observation.[90][91] |

| 18 March 2014 | Bundaberg, Queensland | Unvaccinated horse euthanased.[92] |

| 1 June 2014 | Beenleigh, Queensland | Horse euthanased and property quarantined after outbreak at a property.[93] |

| 24 Jun 2015 | Mullumbimby, New South Wales | Horse found dead after several days of illness. HeV confirmed as the cause of death.[94] |

| 18 March 2014 | Bundaberg, Queensland | Unvaccinated horse euthanased.[92] |

| 1 June 2014 | Beenleigh, Queensland | Horse euthanased and property quarantined after outbreak at a property.[93] |

| 20 July 2014 | Calliope, Queensland | Horse euthanased and property quarantined after outbreak.[95] |

| 24 Jun 2015 | Mullumbimby, New South Wales | Horse found dead after several days of illness.[94] |

| About 20 July 2015 | Atherton Tableland, Queensland | Infected horse died and property quarantined.[96] |

| About 4 September 2015 | Lismore, New South Wales | Infected horse euthanised and property quarantined.[97] |

| About 24 May 2017 | Gold Coast, Queensland | An unvaccinated infected horse euthanised and property quarantined.[98] |

| About 8 July 2017 | Lismore, New South Wales | Hendra virus confirmed near Lismore[99] |

| About 1 August 2017 | Murwillumbah, New South Wales | Hendra virus confirmed near Murwillumbah[100] |

| About 5 August 2017 | Lismore, New South Wales | Third Hendra case confirmed near Lismore[101] |

| 7 June 2019 | Scone, New South Wales | An unvaccinated mare contracted Hendra and had to be euthanased[102] |

Events of June–August 2011

In the years 1994–2010, fourteen events were recorded. Between 20 June 2011 and 28 August 2011, a further seventeen events were identified, during which twenty-one horses died.

It's not clear why there has been a sudden increase in the number of spillover events between June and August 2011. Typically HeV spillover events are more common between May and October. This time is sometimes called "Hendra Season",[103] which is a time when there are large numbers of fruit bats of all species congregated in SE Queensland's valuable winter foraging habitat. The weather (warm and humid) is favourable to the survival of henipavirus in the environment.[104]

It is possible flooding in SE Queensland and Northern NSW in December 2010 and January 2011 may have affected the health of the fruit bats. Urine sampling in flying fox camps indicate that a larger proportion of flying foxes than usual are shedding live virus. Biosecurity Queensland's ongoing surveillance usually shows 7% of the animals are shedding live virus. In June and July nearly 30% animals have been reported to be shedding live virus.[105] Present advice is that these events are not being driven by any mutation in HeV itself.[106]

Other suggestions include that an increase in testing has led to an increase in detection. As the actual mode of transmission between bats and horses has not been determined, it is not clear what, if any, factors can increase the chance of infection in horses.[107]

Following the confirmation of a dog with HeV antibodies, on 27 July 2011, the Queensland and NSW governments will boost research funding into the Hendra virus by $6 million to be spent by 2014–2015. This money will be used for research into ecological drivers of infection in the bats and the mechanism of virus transmission between bats and other species.[108][109] A further 6 million dollars was allocated by the federal government with the funds being split, half for human health investigations and half for animal health and biodiversity research.[110]

Prevention, detection and treatment

Three main approaches are currently followed to reduce the risk to humans.[111]

- Vaccine for horses.

- In November 2012, a vaccine became available for horses. The vaccine is to be used in horses only, since, according to CSIRO veterinary pathologist Dr Deborah Middleton, breaking the transmission cycle from flying foxes to horses prevents it from passing to humans, as well as, "a vaccine for people would take many more years."[112][113]

- The vaccine is a subunit vaccine that neutralises Hendra virus and is composed of a soluble version of the G surface antigen on Hendra virus and has been successful in ferret models.[114][115][116]

- By December 2014, about 300 000 doses had been administered to more than 100 000 horses. About 3 in 1000 had reported incidents; the majority being localised swelling at the injection site. There had been no reported deaths.[117]

- In August 2015, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) registered the vaccine. In its statement the Australian government agency released all its data on reported side effects.[118] In January 2016, APVMA approved its use in pregnant mares.[119]

- Stall-side test to assist in diagnosing the disease in horses rapidly.

- Although the research on the Hendra virus detection is ongoing, a promising result has found using antibody-conjugated magnetic particles and quantum dots.[120][121]

- Post-exposure treatment for humans.

- Nipah virus and Hendra virus are closely related paramyxoviruses that emerged from bats during the 1990s to cause deadly outbreaks in humans and domesticated animals. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-supported investigators developed vaccines for Nipah and Hendra virus based on the soluble G-glycoproteins of the viruses formulated with adjuvants. Both vaccines have been shown to induce strong neutralizing antibodies in different laboratory animals.

- Trials began in 2015 to evaluate a monoclonal antibody to be used as a possible complementary treatment for humans exposed to Hendra virus infected horses.[122]

- Deforestation Impact.

- When considering any zoonosis, one must understand the social, ecological, and biological contributions that may be facilitating this spillover. Hendra virus is believed to be partially seasonally related. For, there is a suggested correlation between breeding time and an increase in incidences of Hendra virus in flying fox bats.[123][124]

- Additionally, recent research suggests that the upsurge in deforestation within Australia may be leading to an increase in incidences of Hendra virus. Flying fox bats tend to feed in trees during a large part of the year. However, due to the lack of specific fruit trees within the area, these bats are having to relocate and thereby are coming into contact with horses more often. The two most recent outbreaks of Hendra virus in 2011 and 2013 appear to be related to an increased level of nutritional stress among the bats as well as relocation of bat populations. Work is currently being done to increase vaccination among horses as well as replant these important forests as feeding grounds for the flying fox bats. Through these measures, the goal is to decrease the incidences of the highly fatal Hendra virus.[124]

Pathology

Flying foxes experimentally infected with the Hendra virus develop a viraemia and shed the virus in their urine, faeces and saliva for approximately one week. There is no other indication of an illness in them.[125] Symptoms of Hendra virus infection of humans may be respiratory, including hemorrhage and edema of the lungs, or in some cases viral meningitis. In horses, infection usually causes pulmonary oedema, congestion and / or neurological signs.[126]

Ephrin B2 has been identified as the main receptor for the henipaviruses.[127]

Viruses of this genus can only be studied in a BSL4 compliant laboratory.

Nipah virus

Emergence

The first cases of Nipah virus infection were identified in 1998, when an outbreak of neurological and respiratory disease on pig farms in peninsular Malaysia resulted in 265 human cases, including 105 human deaths.[20][128][129] The virus itself was isolated the following year in 1999.[130] This outbreak resulted in the culling of one million pigs. In Singapore, 11 cases, including one death, occurred in abattoir workers exposed to pigs imported from the affected Malaysian farms. The Nipah virus has been classified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a Category C agent.[131] The name "Nipah" refers to the place, Sungai Nipah in Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan, the source of the human case from which Nipah virus was first isolated.[132][133] Nipah virus is one of several viruses identified by WHO as a likely cause of a future epidemic in a new plan developed after the Ebola epidemic for urgent research and development before and during an epidemic toward new diagnostic tests, vaccines and medicines.[134][135]

The outbreak was originally mistaken for Japanese encephalitis, but physicians in the area noted that persons who had been vaccinated against Japanese encephalitis were not protected in the epidemic, and the number of cases among adults was unusual.[136] Despite the fact that these observations were recorded in the first month of the outbreak, the Ministry of Health failed to react accordingly, and instead launched a nationwide campaign to educate people on the dangers of Japanese encephalitis and its vector, Culex mosquitoes.

Symptoms of infection from the Malaysian outbreak were primarily encephalitic in humans and respiratory in pigs. Later outbreaks have caused respiratory illness in humans, increasing the likelihood of human-to-human transmission and indicating the existence of more dangerous strains of the virus.

Based on seroprevalence data and virus isolations, the primary reservoir for Nipah virus was identified as Pteropid fruit bats, including Pteropus vampyrus (large flying fox), and Pteropus hypomelanus (small flying fox), both of which occur in Malaysia.

The transmission of Nipah virus from flying foxes to pigs is thought to be due to an increasing overlap between bat habitats and piggeries in peninsular Malaysia. At the index farm, fruit orchards were in close proximity to the piggery, allowing the spillage of urine, faeces and partially eaten fruit onto the pigs.[137] Retrospective studies demonstrate that viral spillover into pigs may have been occurring in Malaysia since 1996 without detection.[20] During 1998, viral spread was aided by the transfer of infected pigs to other farms, where new outbreaks occurred.

Evolution

The most likely origin of this virus was in 1947 (95% credible interval: 1888–1988).[138] There are two clades of this virus—one with its origin in 1995 (95% credible interval: 1985–2002) and a second with its origin in 1985 (95% credible interval: 1971–1996). The mutation rate was estimated to be 6.5 × 10−4 substitution/site/year (95% credible interval: 2.3 × 10−4 –1.18 × 10−3), similar to other RNA viruses.

Outbreaks

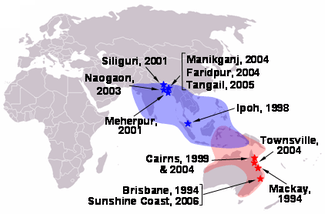

Eight more outbreaks of Nipah virus have occurred since 1998, all within Bangladesh and neighbouring parts of India. The outbreak sites lie within the range of Pteropus species (Pteropus giganteus). As with Hendra virus, the timing of the outbreaks indicates a seasonal effect. Cases occurring in Bangladesh during the winters of 2001, 2003, and 2004 were determined to have been caused by the Nipah virus.[139] In February 2011, a Nipah outbreak began at Hatibandha Upazila in the Lalmonirhat District of northern Bangladesh. As of 7 February 2011 there had been 24 cases and 17 deaths in this outbreak.[140]

- 2001 January 31–23 February, Siliguri, India: 66 cases with a 74% mortality rate.[141] 75% of patients were either hospital staff or had visited one of the other patients in hospital, indicating person-to-person transmission.

- 2001 April – May, Meherpur District, Bangladesh: 13 cases with nine fatalities (69% mortality).[142]

- 2003 January, Naogaon District, Bangladesh: 12 cases with eight fatalities (67% mortality).[142]

- 2004 January – February, Manikganj and Rajbari districts, Bangladesh: 42 cases with 14 fatalities (33% mortality).

- 2004 19 February – 16 April, Faridpur District, Bangladesh: 36 cases with 27 fatalities (75% mortality). 92% of cases involved close contact with at least one other person infected with Nipah virus. Two cases involved a single short exposure to an ill patient, including a rickshaw driver who transported a patient to hospital. In addition, at least six cases involved acute respiratory distress syndrome, which has not been reported previously for Nipah virus illness in humans.

- 2005 January, Tangail District, Bangladesh: 12 cases with 11 fatalities (92% mortality). The virus was probably contracted from drinking date palm juice contaminated by fruit bat droppings or saliva.[143]

- 2007 February – May, Nadia District, India: up to 50 suspected cases with 3–5 fatalities. The outbreak site borders the Bangladesh district of Kushtia where eight cases of Nipah virus encephalitis with five fatalities occurred during March and April 2007. This was preceded by an outbreak in Thakurgaon during January and February affecting seven people with three deaths.[144] All three outbreaks showed evidence of person-to-person transmission.

- 2008 February – March, Manikganj and Rajbari districts, Bangladesh: Nine cases with eight fatalities.[145]

- 2010 January, Bhanga subdistrict, Faridpur, Bangladesh: Eight cases with seven fatalities. During March, one physician of Faridpur Medical College Hospital caring for confirmed Nipah cases died[146]

- 2011 February: An outbreak of Nipah Virus occurred at Hatibandha, Lalmonirhat, Bangladesh. The deaths of 21 schoolchildren due to Nipah virus infection were recorded on 4 February 2011. IEDCR confirmed the infection was due to this virus.[147] Local schools were closed for one week to prevent the spread of the virus. People were also requested to avoid consumption of uncooked fruits and fruit products. Such foods, contaminated with urine or saliva from infected fruit bats, were the most likely source of this outbreak.[148]

- 2018 May: Deaths of seventeen[149] people in Perambra near Calicut, Kerala, India were confirmed to be due to the virus. Treatment using antivirals such as Ribavirin was initiated.[150][151]

- 2019 June: A 23 year-old student was admitted into hospital with Nipah virus infection at Kochi in Kerala.[152] Health Minister of Kerala, K. K. Shailaja confirmed that 86 people who have had recent interactions with the patient were under observation. This included two nurses who treated the patient, and had fever and sore throat. The situation was monitored and precautionary steps were taken to control the spread of virus by the Central[153] and State Government.[152]

- 2019 July: 338 people were kept under observation and 17 of them in isolation by the Health Department of Kerala. After undergoing treatment for 54 days at a private hospital, the 23 year-old student was discharged. On the 23rd of July, the Kerala government declared Ernakulam district to be Nipah-free.[154]

Nipah virus has been isolated from Lyle's flying fox (Pteropus lylei) in Cambodia[155] and viral RNA found in urine and saliva from P. lylei and Horsfield's roundleaf bat (Hipposideros larvatus) in Thailand.[156] Infective virus has also been isolated from environmental samples of bat urine and partially eaten fruit in Malaysia.[157] Antibodies to henipaviruses have also been found in fruit bats in Madagascar (Pteropus rufus, Eidolon dupreanum)[158] and Ghana (Eidolon helvum)[159] indicating a wide geographic distribution of the viruses. No infection of humans or other species have been observed in Cambodia, Thailand or Africa as of May 2018. Now in 4 June 2019, the virus is again spotted in Kerala, India

Ephrin B2 has been identified as the main receptor for the henipaviruses.[127]

Cedar virus

Emergence

Cedar Virus (CedV) was first identified in pteropid urine during work on Hendra virus undertaken in Queensland in 2009.[160]

Although the virus is reported to be very similar to both Hendra and Nipah viruses, it does not cause illness in laboratory animals usually susceptible to paramyxoviruses. Animals were able to mount an effective response and create effective antibodies.[160]

The scientists who identified the virus report:

- Hendra and Nipah viruses are 2 highly pathogenic paramyxoviruses that have emerged from bats within the last two decades. Both are capable of causing fatal disease in both humans and many mammal species. Serological and molecular evidence for henipa-like viruses have been reported from numerous locations including Asia and Africa, however, until now no successful isolation of these viruses have been reported. This paper reports the isolation of a novel paramyxovirus, named Cedar virus, from fruit bats in Australia. Full genome sequencing of this virus suggests a close relationship with the henipaviruses. Antibodies to Cedar virus were shown to cross react with, but not cross neutralize Hendra or Nipah virus. Despite this close relationship, when Cedar virus was tested in experimental challenge models in ferrets and guinea pigs, we identified virus replication and generation of neutralizing antibodies, but no clinical disease was observed. As such, this virus provides a useful reference for future reverse genetics experiments to determine the molecular basis of the pathogenicity of the henipaviruses.[160]

Causes of emergence

The emergence of henipaviruses parallels the emergence of other zoonotic viruses in recent decades. SARS coronavirus, Australian bat lyssavirus, Menangle virus and probably Ebola virus and Marburg virus are also harbored by bats and are capable of infecting a variety of other species. The emergence of each of these viruses has been linked to an increase in contact between bats and humans, sometimes involving an intermediate domestic animal host. The increased contact is driven both by human encroachment into the bats’ territory (in the case of Nipah, specifically pigpens in said territory) and by movement of bats towards human populations due to changes in food distribution and loss of habitat.

There is evidence that habitat loss for flying foxes, both in South Asia and Australia (particularly along the east coast) as well as encroachment of human dwellings and agriculture into the remaining habitats, is creating greater overlap of human and flying fox distributions.

See also

- Animal viruses

- Contagion (film)—A 2011 speculative fiction film about a Hendra virus pandemic

- Paramyxovirus

- Virus (film)

References

- Rima, B; Balkema-Buschmann, A; Dundon, WG; Duprex, P; Easton, A; Fouchier, R; Kurath, G; Lamb, R; Lee, B; Rota, P; Wang, L; ICTV Report Consortium (December 2019). "ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Paramyxoviridae". The Journal of General Virology. 100 (12): 1593–1594. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001328. PMID 31609197.

- "ICTV Report Paramyxoviridae".

- Li, Y; Wang, J; Hickey, AC; Zhang, Y; Li, Y; Wu, Y; Zhang, Huajun; et al. (December 2008). "Antibodies to Nipah or Nipah-like viruses in bats, China [letter]". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 14 (12): 1974–6. doi:10.3201/eid1412.080359. PMC 2634619. PMID 19046545.

- Sawatsky (2008). "Hendra and Nipah Virus". Animal Viruses: Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-22-6.

- "Nipah yet to be confirmed, 86 under observation: Shailaja". OnManorama. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- Drexler JF, Corman VM, Gloza-Rausch F, Seebens A, Annan A (2009). Markotter W (ed.). "Henipavirus RNA in African Bats". PLoS ONE. 4 (7): e6367. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.6367D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006367. PMC 2712088. PMID 19636378.

- Drexler JF, Corman VM, et al. Bats host major mammalian paramyxoviruses. Nat Commun. 2012 Apr 24;3:796. doi:10.1038/ncomms1796

- Amarasinghe, Gaya K.; Bào, Yīmíng; Basler, Christopher F.; Bavari, Sina; Beer, Martin; Bejerman, Nicolás; Blasdell, Kim R.; Bochnowski, Alisa; Briese, Thomas (7 April 2017). "Taxonomy of the order Mononegavirales: update 2017". Archives of Virology. 162 (8): 2493–2504. doi:10.1007/s00705-017-3311-7. ISSN 1432-8798. PMC 5831667. PMID 28389807.

- Hyatt AD, Zaki SR, Goldsmith CS, Wise TG, Hengstberger SG (2001). "Ultrastructure of Hendra virus and Nipah virus within cultured cells and host animals". Microbes and Infection. 3 (4): 297–306. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01383-1. PMID 11334747.

- Bonaparte, M; Dimitrov, A; Bossart, K (2005). "Ephrin-B2 ligand is a functional receptor for Hendra virus and Nipah virus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (30): 10652–7. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10210652B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504887102. PMC 1169237. PMID 15998730.

- Negrete OA, Levroney EL, Aguilar HC (2005). "EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus". Nature. 436 (7049): 401–5. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..401N. doi:10.1038/nature03838. PMID 16007075.

- Bowden, Thomas A.; Crispin, Max; Jones, E. Yvonne; Stuart, David I. (1 October 2010). "Shared paramyxoviral glycoprotein architecture is adapted for diverse attachment strategies". Biochemical Society Transactions. 38 (5): 1349–1355. doi:10.1042/BST0381349. PMC 3433257. PMID 20863312.

- Bowden, Thomas A.; Crispin, Max; Harvey, David J.; Aricescu, A. Radu; Grimes, Jonathan M.; Jones, E. Yvonne; Stuart, David I. (1 December 2008). "Crystal Structure and Carbohydrate Analysis of Nipah Virus Attachment Glycoprotein: a Template for Antiviral and Vaccine Design". Journal of Virology. 82 (23): 11628–11636. doi:10.1128/JVI.01344-08. PMC 2583688. PMID 18815311.

- Wang L, Harcourt BH, Yu M (2001). "Molecular biology of Hendra and Nipah viruses". Microbes and Infection. 3 (4): 279–87. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01381-8. PMID 11334745.

- Kolakofsky, D; Pelet, T; Garcin, D; Hausmann, S; Curran, J; Roux, L (February 1998). "Paramyxovirus RNA synthesis and the requirement for hexamer genome length: the rule of six revisited". Journal of Virology. 72 (2): 891–9. PMC 124558. PMID 9444980.

- Selvey LA, Wells RM, McCormack JG (1995). "Infection of humans and horses by a newly described morbillivirus". Medical Journal of Australia. 162 (12): 642–5. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb126050.x. PMID 7603375.

- Benson, Bruce (1994–2011). Vic Rail and Hendra Virus films 1991-2011 (Motion picture). Australia: State Library of Queensland.

- "Hendra virus: the initial research". Department of Employment, Economic Development, and Innovation, Queensland Primary Industries and Fisheries. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Peacock, Mark (29 October 1995). "Outbreak At Victory Lodge". Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Field, H; Young, P; Yob, JM; Mills, J; Hall, L; MacKenzie, J (2001). "The natural history of Hendra and Nipah viruses". Microbes and Infection. 3 (4): 307–14. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01384-3. PMID 11334748.

- Walker, Jamie (23 July 2011). "Hendra death toll hits 13 for month". The Australian. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- Quammen, David. Spillover: Animal Infections and the next Human Pandemic. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012. Print.

- Field, H; de Jong, C; Melville, D; Smith, C; Smith, I; Broos, A; Kung, YH; McLaughlin, A; Zeddeman, A (2011). Fooks, Anthony R (ed.). "Hendra virus infection dynamics in Australian fruit bats". PLoS ONE. 6 (12): e28678. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628678F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028678. PMC 3235146. PMID 22174865.

- "Chief vet says dog hendra case 'unprecedented'". 612 ABC Brisbane. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "Little Red Flying Fox (Pteropus scapulatus)". Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- Plowright RK, Field HE, Smith C, Divljan A, Palmer C, Tabor G, Daszak P, Foley JE (2008). "Reproduction and nutritional stress are risk factors for Hendra virus infection in little red flying foxes (Pteropus scapulatus)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1636): 861–869. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1260. PMC 2596896. PMID 18198149.

- Smith, C; et al. (17 June 2014). "Flying-Fox Species Density - A Spatial Risk Factor for Hendra Virus Infection in Horses in Eastern Australia". PLoS ONE. 9 (6): e99965. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...999965S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099965. PMC 4061024. PMID 24936789.

- Fogarty, R; Halpin, Kim; et al. (2008). "Henipavirus susceptibility to environmental variables". Virus Research. 132 (1–2): 140–144. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.11.010. PMC 3610175. PMID 18166242.

- Selvey L (28 October 1996). "Screening of Bat Carers for Antibodies to Equine Morbillivirus" (PDF). CDI. 20 (22): 477–478.

- Pain, Stephanie (17 October 2015). "The real batman". New Scientist. 228 (3043): 47. Bibcode:2015NewSc.228...47P. doi:10.1016/s0262-4079(15)31425-1.

Last year, the government of New South Wales sanctioned the destruction of colonies of flying foxes. Why? In 1996, Hendra virus was discovered in Australia.

- Field, HE; Barratt, PC; Hughes, RJ; Shield, J; Sullivan, ND (2000). "A fatal case of Hendra virus infection in a horse in north Queensland: clinical and epidemiological features". Australian Veterinary Journal. 78 (4): 279–80. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2000.tb11758.x. PMID 10840578.

- Hanna, JN; McBride, WJ; Brookes, DL (2006). "Hendra virus infection in a veterinarian". Medical Journal of Australia. 185 (10): 562–4. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00692.x. PMID 17115969.

- "Notifiable Diseases: Hendra Virus" (PDF). Animal Health Surveillance. 4: 4–5. 2006. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ProMED-mail. Hendra virus, human, equine – Australia (Queensland) (03): correction. ProMED-mail 2007; 3 September: 20070903.2896.

- "Queensland vet dies from Hendra virus". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 August 2008.

- Brown, Kimberly S (23 August 2008). "Horses and Human Die in Australia Hendra Outbreak; Government Comes Under Fire". The Horse. Retrieved 26 August 2008.

- Perkins, Nigel (2 December 2008) "Independent review of Hendra virus cases at Redlands and Proserpine in July and August 2008". (the 2008 Perkins Review). dpi.qld.gov.au

- "Vet tests positive to Hendra virus". The Australian. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- Natasha Bita (2 September 2009). "Alister Rodgers dies of Hendra virus after 2 weeks in coma". The Australian. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "Horse dies from Hendra virus in Queensland". news.com.au. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- "Biosecurity Queensland". Facebook. 1 July 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- "Biosecurity Queensland confirms second Hendra case in South East Queensland". Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. 2 July 2011. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012.

- "Another confirmed horse with Hendra virus at Mt Alford". Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. 4 July 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- "Hendra virus infection confirmed in a dog". Facebook. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Agius, Kym; Marszalek, Jessica; Berry, Petrina (26 July 2011). "Scientists guessing over Hendra dog". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Marszalek, Jessica (31 July 2011). "Dog put down after more Hendra tests". The Sydney Morning Herald. Australian Associated Press. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- Calligeros, Marissa (29 June 2011). "Eight face Hendra tests after horse's death". Brisbane Times. Australian Associated Press. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- "Biosecurity Queensland adds Logan result to confirmed Hendra cases". Facebook. 21 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- Miles, Janelle; Robertson, Josh (26 July 2011). "Biosecurity Queensland investigates possible Hendra virus case near Chinchilla". The Courier-Mail. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "Confirmed case of hendra virus on NSW North Coast". 1 July 2014. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- Joyce, Jo (11 October 2011). "Hendra horse owners speak out". ABC North Coast NSW. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- "Biosecurity Bulletin" (PDF) (Press release). NSW Government Department of Primary Industries. 13 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- "Second case of Hendra virus in NSW near Macksville". dpi.nsw.gov.au. 7 July 2011

- "Second horse dies from Hendra in New South Wales on property near Macksville". Australian Associated Press. 7 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "Update: Hendra virus infection confirmed at Park Ridge" (Press release). Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. 5 July 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Hurst, Daniel (12 July 2011). "Hendra outbreak at LNP candidate's horse riding property". Brisbane Times. Australian Associated Press. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- "Hendra virus case confirmed in Hervey Bay" (Press release). Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. 16 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- "Fourth NSW horse dies from Hendra virus". Australian Associated Press. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "Hendra virus case confirmed in Boondall area" (Press release). Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. 16 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- "Hendra virus case confirmed in Chinchilla area". Facebook. 23 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "Fifth Hendra case confirmed at Mullumbimby" (Press release). NSW Department of Primary Industries. 28 July 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Biosecurity Bulletin" (PDF) (Press release). NSW Department of Primary Industries. 18 August 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- "Biosecurity Bulletin" (PDF) (Press release). NSW Department of Primary Industries. 17 August 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- Stephanie Small (23 August 2011). "Another Hendra outbreak in Queensland". Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- "Biosecurity Bulletin" (PDF) (Press release). NSW Department of Primary Industries. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- "New Hendra Virus Case in Caboolture Area". Facebook. 10 October 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- "Second Hendra virus case confirmed at Beachmere property October 15, 2011 at 1:42am". Facebook Notes. 15 October 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- "New Hendra virus case in Townsville area". Facebook. 4 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- "Two new Hendra virus cases confirmed". Facebook. 29 May 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- "Quarantine lifted after Hendra outbreaks". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 12 July 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- "Hendra virus quarantines lifted in Ingham and Rockhampton". Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. 12 July 2012. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013.

- Guest, Annie (20 July 2014). "Hendra virus found in Rockhampton". PM. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- "Horses put down after showing Hendra symptoms". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 27 July 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Two horses euthanased on Rockhampton property". Facebook. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "New Hendra virus case in Mackay". Facebook. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- "New Hendra virus case in Cairns area". Facebook. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Testing underway after latest Hendra outbreak". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 September 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- "New twist to Port Douglas Hendra death". Horse Zone. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- "Horse dead after contracting Hendra virus". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Horses to be tested after Hendra virus outbreak". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 4 November 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- "Horse dies from Hendra virus near Mackay". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 23 January 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- "New Hendra virus case confirmed in Qld". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- Honan, Kim (10 June 2013). "First NSW Hendra horse death in two years". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Burgess, Sam (4 July 2013). "Second Brisbane Valley property faces Hendra virus lockdown". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- Campbell, Camilla (6 July 2013). "Hendra Outbreak Again in Macksville". NBN News. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- "New Hendra case confirmed on NSW mid north coast" (Press release). NSW Department of Primary Industries. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- "Dog infected with Hendra". The Land. NSW Department of Primary Industries. 20 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- "New Hendra virus case confirmed on Gold Coast". Facebook. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- "Third Hendra case confirmed west of Kempsey" (Press release). NSW Department of Primary Industries. 8 July 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- "Hendra virus claims fourth horse death on NSW mid north coast" (Press release). NSW Department of Primary Industries. 10 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Fourth horse dies of Hendra virus at Kempsey on NSW mid north coast". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- Jo Skinner (19 May 2014). "Tests reveal Hendra virus in horse on southern Qld property". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- "Hendra virus outbreak south of Brisbane" – Australian Broadcasting Corporation – Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- "Hendra virus confirmed on NSW north coast" – NSW Department of Primary Industries – Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- Sawyer, Scott. "Officers still on scene at Hendra virus property". Gladstone Observer. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- "Hendra virus case confirmed after horse dies in North Queensland". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- "Horse dead from Hendra near Lismore in northern New South Wales - By Kim Honan". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 4 September 2015. 4 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "New Hendra virus case confirmed in Gold Coast Hinterland". Biosecurity Queensland. 26 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Hendra virus confirmed near Lismore - By NSW DPI". NSW Department of Primary Industries. 9 July 2017. 9 July 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- "Hendra virus confirmed near Murwillumbah - By NSW DPI". NSW Department of Primary Industries. 2 August 2017. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- "Third Hendra case confirmed". NSW Department of Primary Industries. NSW Department of Primary Industries. 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- "Potentially deadly Hendra virus spreads further south in New South Wales". ABC. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Epidemiological methodology of communicating higher contagion periods for better common, non-scientific individual understanding

- Fogarty, R. D.; Halpin, K.; Hyatt, A. D.; Daszak, P.; Mungall, B. A. (2008). "Henipavirus susceptibility to environmental variables". Virus Research. 132 (1–2): 140–144. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.11.010. PMC 3610175. PMID 18166242.

- Tony Moore (28 July 2011). "Nearly a third of bats now carry Hendra: researchers". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Janelle Miles; Andrew MacDonald; Koren Helbig (29 July 2011). "Fearon family plead with authorities for stay of execution for Hendra positive dog Dusty". The Courier-Mail. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- Emma Sykes (4 July 2011). "Hendra virus research continues as more horses contract the disease". 612 ABC Brisbane. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- "New hunt for Hendra in other species". The Sydney Morning Herald. Australian Associated Press. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- Guest, Annie (27 July 2011). "Urgent funds for hendra research". The World Today. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Gillard Government helping in response to Hendra". 29 July 2011. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012.

- "Opinion: combating the deadly Hendra virus". CSIRO. 13 May 2011. Archived from the original on 24 November 2012.

- "Equine Henda Virus Vaccine Launched in Australia". The Horse. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- Taylor, John; Guest, Annie (1 November 2012). "Breakthrough Hendra virus vaccine released for horses". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- Pallister, J; Middleton, D; Wang, LF (2011). "A recombinant Hendra virus G glycoprotein-based subunit vaccine protects ferrets from lethal Hendra virus challenge". Vaccine. 29 (24): 5623–30. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.015. PMC 3153950. PMID 21689706.

- Fraser, Kelmeny (24 July 2011). "Hendra virus scientists push for vaccine to be fast-tracked". The Sunday Mail. Queensland. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Hendra vaccine could be ready in 2012". Australian Associated Press. 17 May 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- "Autopsy carried out on exhumed horse to determine if Hendra vaccine caused its death - By Marty McCarthy". Australian Broadcasting Corporation 30 December 2014. 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- "Chemical regulator registers Hendra vaccine, releases data on reported side effects - By Marty McCarthy". Australian Broadcasting Corporation 5 August 2015. 4 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "Hendra vaccine approved for use in pregnant mares - By Kim Honan". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 29 January 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- Huw Morgan (20 September 2012). "A 'quantum' step towards on-the-spot Hendra virus detection". news@CSIRO. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- Lisi F, Falcaro P, Buso B, Hill AJ, Barr JA, Crameri G, Nguyen TL, Wang LF, Mulvaney P (2012). "Rapid Detection of Hendra Virus Using Magnetic Particles and Quantum Dots". Advanced Healthcare Materials. 1 (5): 631–634. doi:10.1002/adhm.201200072. PMID 23184798.

- - By Robin McConchie (April 2015). "Hendra trials for humans about treatment not prevention". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Plowright, R. K. et al. (2008, January 15). Reproduction and nutritional stress are risk factors for Hendra virus infection in little red flying foxes (Pteropus scapulatus).http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/royprsb/275/1636/861.full.pdf

- Plowright RK et al. 2015 Ecological dynamics of emerging bat virus spillover. Proc. R. Soc. B 282: 20142124.https://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2124

- Edmondston, Jo; Field, Hume (2009). "Research update: Hendra Virus" (PDF). Australian Biosecurity CRC for Emerging Infectious Disease. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Middleton, D. "1Initial experimental characterisation of HeV (Redland Bay 2008) infection in horses" (PDF). Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Lee B, Ataman ZA; Ataman (2011). "Modes of paramyxovirus fusion: a Henipavirus perspective". Trends in Microbiology. 19 (8): 389–399. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2011.03.005. PMC 3264399. PMID 21511478.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (30 April 1999). "Update: outbreak of Nipah virus—Malaysia and Singapore, 1999". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 48 (16): 335–7. PMID 10366143.

- Lai-Meng Looi; Kaw-Bing Chua (2007). "Lessons from the Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia" (PDF). Department of Pathology, University of Malaya and National Public Health Laboratory of the Ministry of Health, Malaysia. 29 (2): 63–67. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2019 – via The Malaysian Journal of Pathology.

- "Nipah Virus (NiV) CDC". www.cdc.gov. CDC. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Bioterrorism Agents/Diseases. bt.cdc.gov

- Siva SR, Chong HT, Tan CT (2009). "Ten year clinical and serological outcomes of Nipah virus infection" (PDF). Neurology Asia. 14: 53–58.

- "Spillover — Zika, Ebola & Beyond". pbs.org. PBS. 3 August 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Kieny, Marie-Paule. "After Ebola, a Blueprint Emerges to Jump-Start R&D". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "LIST OF PATHOGENS". World Health Organization. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "Dobbs and the viral encephalitis outbreak".. Archived thread from the Malaysian Doctors Only BBS Archived 18 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Chua KB, Chua BH, Wang CW (2002). "Anthropogenic deforestation, El Niño and the emergence of Nipah virus in Malaysia". The Malaysian Journal of Pathology. 24 (1): 15–21. PMID 16329551.

- Lo Presti A, Cella E, Giovanetti M, Lai A, Angeletti S, Zehender G, Ciccozzi M (2015). "Origin and evolution of Nipah virus". J Med Virol. 88 (3): 380–388. doi:10.1002/jmv.24345. PMID 26252523.

- Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L, Rota PA, Rollin PE, Bellini WJ, Ksiazek TG, Mishra A (February 2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748.

- "Nipah Outbreak at Lalmonirhat". Bangladesh: Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research. 7 February 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- Chadha MS, Comer JA, Lowe L (2006). "Nipah virus-associated encephalitis outbreak, Siliguri, India". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 235–40. doi:10.3201/eid1202.051247. PMC 3373078. PMID 16494748.

- Hsu VP, Hossain MJ, Parashar UD (2004). "Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (12): 2082–7. doi:10.3201/eid1012.040701. PMC 3323384. PMID 15663842.

- ICDDR,B (2005). "Nipah virus outbreak from date palm juice". Health and Science Bulletin. 3 (4): 1–5. Archived from the original on 10 December 2006.

- ICDDR,B (2007). "Person-to-person transmission of Nipah infection in Bangladesh". Health and Science Bulletin. 5 (4): 1–6. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009.

- ICDDR,B (2008). "Outbreaks of Nipah virus in Rajbari and Manikgonj". Health and Science Bulletin. 6 (1): 12–3. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009.

- ICDDR,B (2010). "Nipah outbreak in Faridpur District, Bangladesh, 2010". Health and Science Bulletin. 8 (2): 6–11. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- "Arguments in Bahodderhat murder case begin". The Daily Star. 18 March 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- তাহেরকে ফাঁসি দেওয়ার সিদ্ধান্ত নেন জিয়া. prothom-alo.com. 4 February 2011

- "Nipah virus outbreak: Death toll rises to 14 in Kerala, two more cases confirmed". indianexpress.com. 27 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- "Kozhikode on high alert as three deaths attributed to Nipah virus". The Indian Express. 20 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- "Deadly Nipah virus claims victims in India". BBC News. 21 May 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- "Kerala Govt Confirms Nipah Virus, 86 Under Observation". New Delhi. 4 June 2019. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Sharma, Neetu Chandra (4 June 2019). "Centre gears up to contain re-emergence of Nipah virus in Kerala". Mint. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- KochiJuly 23, Press Trust of India; July 23, 2019UPDATED; Ist, 2019 19:32. "Ernakulam district declared Nipah virus free, says Kerala health minister". India Today. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- Reynes JM, Counor D, Ong S (2005). "Nipah virus in Lyle's flying foxes, Cambodia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (7): 1042–7. doi:10.3201/eid1107.041350. PMC 3371782. PMID 16022778.

- Wacharapluesadee S, Lumlertdacha B, Boongird K (2005). "Bat Nipah virus, Thailand". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (12): 1949–51. doi:10.3201/eid1112.050613. PMC 3367639. PMID 16485487.

- Chua KB, Koh CL, Hooi PS (2002). "Isolation of Nipah virus from Malaysian Island flying-foxes". Microbes and Infection. 4 (2): 145–51. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01522-2. PMID 11880045.

- Lehlé C, Razafitrimo G, Razainirina J (2007). "Henipavirus and Tioman virus antibodies in pteropodid bats, Madagascar". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (1): 159–61. doi:10.3201/eid1301.060791. PMC 2725826. PMID 17370536.

- Hayman DT, et al. (2008). Montgomery JM (ed.). "Evidence of henipavirus infection in West African fruit bats". PLoS ONE. 3 (7): 2739. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2739H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002739. PMC 2453319. PMID 18648649.

- Marsh, Glenn A.; de Jong, Carol; Barr, Jennifer A.; Tachedjian, Mary; Smith, Craig; Middleton, Deborah; Yu, Meng; Todd, Shawn; Foord, Adam J.; Haring, Volker; Payne, Jean; Robinson, Rachel; Broz, Ivano; Crameri, Gary; Field, Hume E.; Wang, Lin-Fa (2 August 2012). "Cedar Virus: A Novel Henipavirus Isolated from Australian Bats". PLOS Pathogens. 8 (8): e1002836. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002836. PMC 3410871. PMID 22879820.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henipavirus. |

- ICTV Report: Paramyxoviridae

- Biosecurity Queensland Hendra virus

- The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority - Hendra vaccine registration and data release - August 2015

- Current status of Nipah (virus encephalitis) worldwide at OIE. WAHID Interface - OIE World Animal Health Information Database

- Disease card

- 'hendrafacts'

- ViralZone: Henipavirus

- Hendra virus factsheet – CSIRO

- Nipah virus – CSIRO

- Henipavirus – Henipavirus Ecology Research Group (HERG) INFO

- The science and mystery of hendra virus – by Renee du Preez (ABC Rural) – Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Enserink M (February 2009). "Virus's Achilles' Heel Revealed". Science Now. AAAS. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009.

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Paramyxoviridae