Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma

Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma involving aberrant T cells or null lymphocytes. It is described in detail in the "Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues" edited by experts of the World Health Organisation (WHO). The term anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) encompasses at least four different clinical entities, all sharing the same name, which histologically share the presence of large pleomorphic cells that express CD30 and T-cell markers. Two types of ALCL present as systemic disease and are considered as aggressive lymphomas, while two types present as localized disease and may progress locally. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma is associated with various types of medical implants.[1]

| Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma | |

|---|---|

| |

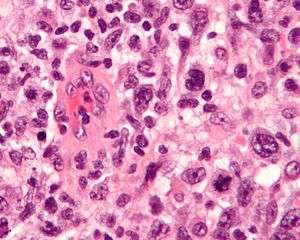

| Micrograph of an anaplastic large cell lymphoma. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Hematology, oncology |

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation varies according to the type of ALCL. Two of the ALCL subtypes are systemic lymphomas, in that they usually present with enlarged lymph nodes in multiple regions of the body, or with tumors outside the lymph nodes (extranodal) such as bone, intestine, muscle, liver, or spleen. These 2 subtypes usually associate with weight loss, fevers and night sweats, and can be lethal if left untreated without chemotherapy.[2] The third type of ALCL is so-called cutaneous ALCL, and is a tumor that presents in the skin as ulcers that may persist, or occasionally may involute spontaneously, and commonly recur. This type of ALCL usually manifests in different regions of the body and may extend to regional lymph nodes, i.e., an axillary lymph node if the ALCL presents in the arm.[3]

A rare subtype of ALCL has been identified in women who have textured silicone breast implants (protheses). This is known as breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma, or BIA-ALCL. It can occur as a result of breast reconstruction after a diagnosis of breast cancer [4] or as a result of cosmetic surgery using textured silicone implants.[5] BIA-ALCL initially occurs in the fluid contained within the scar capsule surrounding the implant, rather than the breast tissue itself. The tumor initially manifests with swelling of the breast due to fluid accumulation around the implant. The disease may progress to invade the tissue surrounding the capsule, and if left untreated may progress to the axillary lymph nodes.[6]

It typically presents at a late stage and is often associated with systemic symptoms ("B symptoms").

Causes

A form of ALCL is associated with implants. Textured breast implants are most commonly identified and have been the focus of research, but tibial implants, dental implants, injection port implants, gluteal implants, and gastric band placement have also been reported.[7] Risk is highest with most strongly textured implants.[8]

Chronic inflammation is known to lead to lymphoma. It has been suggested that inflammation surrounding textured implants causes proliferation and activation of T-cells.[8]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ALCL requires the examination by a pathologist of any enlarged lymph node, or any affected extranodal tissue where there the tumor is found, such as the intestine, the liver or bone in the case of systemic ALCL. For the case of cutaneous ALCL, a skin excision is recommended, and for the diagnosis of ALCL associated with breast implants, a cytologic specimen of the effusion around the breast implant or complete examination of the breast capsule surrounding the implant is required.[9]

Classification

Four forms of anaplastic large cell lymphoma are recognized: primary systemic anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive ALCL, primary systemic ALK-negative ALCL, primary cutaneous ALCL, and breast implant-associated ALCL.[10]

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma is characterized by "hallmark" cells and presence for CD30. Integration of this information with clinical presentation is crucial for final classification and management of patients.

The classification acknowledges the recognition of large cells with pleomorphic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm. Also required in the diagnosis is immunophenotypic evidence that cells are T lymphocytes, such as the expression of immunologic markers CD3 or CD4, but CD30 expression must be present in all neoplastic cells. Out of the 4 types of ALCL, one subtype of systemic ALCL expresses the protein anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK); the other types of ALCL do not express ALK.

The hallmark cells are of medium size and feature abundant cytoplasm (which may be clear, amphophilic or eosinophilic), kidney shaped nuclei, and a paranuclear eosinophilic region. Occasional cells may be identified in which the plane of section passes through the nucleus in such a way that it appears to enclose a region of cytoplasm within a ring; such cells are called "doughnut" cells.

On histological examination, hallmark cells must be present. Where they are not present in large numbers, they are usually located around blood vessels. Morphologic variants include the following types:

- Common (featuring a predominance of hallmark cells)

- Small-cell (featuring smaller cells with the same immunophenotype as the hallmark cells)

- Lymphohistiocytic

- Sarcomatoid

- Signet ring

Immunophenotype

The hallmark cells (and variants) show immunopositivity for CD30[11][12] (also known as Ki-1). True positivity requires localisation of signal to the cell membrane or paranuclear region (cytoplasmic positivity is non-specific). Another useful marker which helps to differentiate this lesion from Hodgkin's lymphoma is clusterin. The neoplastic cells have a golgi staining pattern (hence paranuclear staining), which is characteristic of this lymphoma. The cells are also typically positive for a subset of markers of T-cell lineage. However, as with other T-cell lymphomas, they are usually negative for the pan T-cell marker CD3.

Occasionally cells are of null (neither T nor B) cell type. These lymphomas show immunopositivity for ALK protein in 70% of cases. They are also typically positive for EMA. In contrast to many B-cell anaplastic CD30 positive lymphomas, they are negative for markers of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).

Molecular biology

Greater than 90% of cases contain a clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor. Oncogenic potential is conferred by upregulation of a tyrosine kinase gene on chromosome 2. Several different translocations involving this gene have been identified in cases of this lymphoma. The most common is a chromosomal translocation involving the nucleophosmin gene on chromosome 5. The translocation may be identified by analysis of giemsa-banded metaphase spreads of tumur cells and is characterised by t(2;5)(p23;q35). The product of this fusion gene may be identified by immunohistochemistry for ALK. The nucleophosmin component associated with the commonest translocation results in nuclear positivity as well as cytoplasmic positivity. Positivity with the other translocations may be confined to the cytoplasm.

Differential diagnosis

As the appearance of the hallmark cells, pattern of growth (nesting within lymph nodes) and positivity for EMA may mimic metastatic carcinoma, it is important to include markers for cytokeratin in any diagnostic panel (these will be negative in the case of anaplastic lymphoma). Other mimics include CD30 positive B-cell lymphomas with anaplastic cells (including Hodgkin lymphomas). These are identified by their positivity for markers of B-cell lineage and frequent presence of markers of EBV. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas may also be positive for CD30; these are excluded by their anatomic distribution. ALK positivity may also be seen in some large-cell B-cell lymphomas and occasionally in rhabdomyosarcomas.

Treatment

Anthracycline-based chemotherapy is the recommended initial treatment for ALCL. The most common regimen is CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone).[13] Brentuximab vedotin is approved as a second-line therapy for ALCL.[13] Other second line therapies include GDP (gemcitabine, dexamethasone, cisplatin), DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin), and ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide).[13]

Cutaneous ALCL is typically treated by surgical excision and radiation.[14]

Prognosis

The prognosis varies according with the type of ALCL. During treatment, relapses may occur but these typically remain sensitive to chemotherapy.

Those with ALK positive ALCL have better prognosis than ALK negative ALCL.[13] It has been suggested that ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphomas derive from other T-cell lymphomas that are morphologic mimics of ALCL in a final common pathway of disease progression. Whereas ALK-positive ALCLs are molecularly characterized and can be readily diagnosed, specific immunophenotypic or genetic features to define ALK-negative ALCL are missing and their distinction from other T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (T-NHLs) remains controversial, although promising diagnostic tools for their recognition have been developed and might be helpful to drive appropriate therapeutic protocols.[15]

Systemic ALK+ ALCL 5-year survival: 70–80%.[16] Systemic ALK- ALCL 5-year survival: 15–45%.[16] Primary Cutaneous ALCL: Prognosis is good if there is not extensive involvement regardless of whether or not ALK is positive with an approximately 90% 5-year survival rate.[16] Breast implant-associated ALCL has an excellent prognosis when the lymphoma is confined to the fluid or to the capsule surrounding the breast implant. This tumor can be recurrent and grow as a mass around the implant capsule or can extend to regional lymph nodes if not properly treated.[9]

Epidemiology

The FDA recorded over 450 cases of ALCL due to breast implants between 2010 and 2018.[17]

History

A 2008 study found an increased risk of ALCL of the breast in women with silicone breast implants (protheses), although the overall risk remained exceedingly low due to the rare occurrence of the tumor.[4]

The link between ALCL and breast implants was confirmed by the FDA in 2011.[18][17]

References

- Clemens, Mark; Dixon, J. Michael (30 November 2018). "Breast implants and anaplastic large cell lymphoma". BMJ. 363: k5054. doi:10.1136/bmj.k5054. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 30504242. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Medeiros LJ, Elenitoba-Johnson KS. Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007 May;127(5):707–22.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, Cozzio A, Ortiz-Romero PL, Bagot M, Olsen E, Kim YH, Dummer R, Pimpinelli N, Whittaker S, Hodak E, Cerroni L, Berti E, Horwitz S, Prince HM, Guitart J, Estrach T, Sanches JA, Duvic M, Ranki A, Dreno B, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Knobler R, Wood G, Willemze R. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011 Oct 13;118(15):4024–35.

- de Jong D, Vasmel WL, de Boer JP, et al. (November 2008). "Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in women with breast implants". JAMA. 300 (17): 2030–5. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.585. PMID 18984890.

- Devlin, Hannah; Osborne, Hilary (26 November 2018). "Rare cancer linked to breast implant used by millions of women". The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Miranda RN, Aladily TN, Prince HM, Kanagal-Shamanna R, de Jong D, Fayad LE, Amin MB, Haideri N, Bhagat G, Brooks GS, Shifrin DA, O'Malley DP, Cheah CY, Bacchi CE, Gualco G, Li S, Keech JA Jr, Hochberg EP, Carty MJ, Hanson SE, Mustafa E, Sanchez S, Manning JT Jr, Xu-Monette ZY, Miranda AR, Fox P, Bassett RL, Castillo JJ, Beltran BE, de Boer JP, Chakhachiro Z, Ye D, Clark D, Young KH, Medeiros LJ. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: long-term follow-up of 60 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Jan 10;32(2):114–20.

- Clemens, Mark; Dixon, J. Michael (30 November 2018). "Breast implants and anaplastic large cell lymphoma". BMJ. 363: k5054. doi:10.1136/bmj.k5054. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 30504242.

- Ravnic, Dino J.; Mackay, Donald R.; Potochny, John D.; Rakszawski, Kevin L.; Williams, Nicole C.; Behar, Brittany J.; Leberfinger, Ashley N. (1 December 2017). "Breast Implant–Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: A Systematic Review". JAMA Surgery. 152 (12): 1161–1168. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4026. ISSN 2168-6254. PMID 29049466.

- Miranda RN, Aladily TN, Prince HM, Kanagal-Shamanna R, de Jong D, Fayad LE, Amin MB, Haideri N, Bhagat G, Brooks GS, Shifrin DA, O'Malley DP, Cheah CY, Bacchi CE, Gualco G, Li S, Keech JA Jr, Hochberg EP, Carty MJ, Hanson SE, Mustafa E, Sanchez S, Manning JT Jr, Xu-Monette ZY, Miranda AR, Fox P, Bassett RL, Castillo JJ, Beltran BE, de Boer JP, Chakhachiro Z, Ye D, Clark D, Young KH, Medeiros LJ. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: long-term follow-up of 60 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Jan 10;32(2):114–20.

- Laurent, Camille; Haioun, Corinne; Brousset, Pierre; Gaulard, Philippe (1 September 2018). "New insights into breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma". Current Opinion in Oncology. 30 (5): 292–300. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000476. ISSN 1040-8746. PMID 30096095.

- Watanabe M, Ogawa Y, Itoh K, et al. (January 2008). "Hypomethylation of CD30 CpG islands with aberrant JunB expression drives CD30 induction in Hodgkin lymphoma and anaplastic large cell lymphoma". Lab. Invest. 88 (1): 48–57. doi:10.1038/labinvest.3700696. PMID 17965727.

- Park SJ, Kim S, Lee DH, et al. (August 2008). "Primary systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma in Korean adults: 11 years' experience at Asan Medical Center". Yonsei Med. J. 49 (4): 601–9. doi:10.3349/ymj.2008.49.4.601. PMC 2615286. PMID 18729302.

- "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: Overview, Subtypes of ALCL, Genetic-Molecular Characteristics and Their Effects". 16 November 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Agnelli L, Mereu E, Pellegrino E, Limongi T, et al. (2012). "Identification of a 3-gene model as a powerful diagnostic tool for the recognition of ALK-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma". Blood. 120 (6): 1274–81. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-01-405555. PMID 22740451.

- Liu, Delong (2019-01-09). "Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma". Medscape. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Commissioner, Office of the. "Press Announcements - Statement from Binita Ashar, M.D., of the FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health on agency's continuing efforts to educate patients on known risk of lymphoma from breast implants". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- CNN, Faith Karimi. "FDA reports additional cases of cancer linked to breast implants". CNN. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Information on Anaplastic Large Cell (Ki-1 / CD-30) Lymphomas from Lymphoma Information Network