Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a cancer of B cells, a type of white blood cell responsible for producing antibodies. It is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma among adults,[1] with an annual incidence of 7–8 cases per 100,000 people per year in the USA and the UK.[2][3] This cancer occurs primarily in older individuals, with a median age of diagnosis at approximately 70 years of age,[3] though it can also occur in children and young adults in rare cases.[4] DLBCL is an aggressive tumor which can arise in virtually any part of the body,[5] and the first sign of this illness is typically the observation of a rapidly growing mass, sometimes associated with B symptoms—fever, weight loss, and night sweats.[6]

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | DLBCL or DLBL |

| |

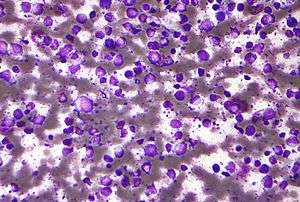

| Micrograph (Field stain) of a diffuse large B cell lymphoma. | |

| Specialty | Hematology and oncology |

The causes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma are not well understood. Usually DLBCL arises from normal B cells, but it can also represent a malignant transformation of other types of lymphoma (particularly marginal zone lymphomas[7]) or leukemia. An underlying immunodeficiency is a significant risk factor.[8] Infections with Helicobacter pylori virus (H. pylori), sometimes termed Helicobacter pylori positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma,[7] and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), termed Epstein Barr virus positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified,[9] have also been found to contribute to the development of some subgroups of DLBCL.

Diagnosis of DLBCL is made by removing a portion of the tumor through a biopsy, and then examining this tissue using a microscope. Usually a hematopathologist makes this diagnosis.[10] Several subtypes of DLBCL have been identified, each having a different clinical presentation and prognosis. However, the usual treatment for each of these is chemotherapy, often in combination with an antibody targeted at the tumor cells.[11] Through these treatments, more than 90 % of patients with DLBCL can be cured,[12] and the overall five-year survival rate for older adults is around 58%.[13]

Signs and symptoms

The most typical symptom at the time of diagnosis is a mass that is rapidly enlarging and located in a part of the body with multiple lymph nodes.[14] Patients commonly present with systemic symptoms such as weight loss, night sweats, fevers, or fatigue.

Most primary CNS lymphomas are diffuse large B cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Therefore, focal neurological deficits, e.g., seizures, may be a presenting sign.

Diagnosis

Classification

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma encompasses a biologically and clinically diverse set of diseases,[15] many of which cannot be separated from one another by well-defined and widely accepted criteria. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification system defines more than a dozen subtypes,[16] each of which can be differentiated based on the location of the tumor, the presence of other cells within the tumor (such as T cells), and whether the patient has certain other illnesses related to DLBCL. One of these well-defined groupings of particular note is "primary mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma", which arises within the thymus or mediastinal lymph nodes.[17]

In some cases, a tumor may share many features with both DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma. In these situations, the tumor is classified as simply “B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Burkitt lymphoma”. A similar situation can arise between DLBCL and Hodgkin lymphoma; the tumor is then classified as “B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma”.

When a case of DLBCL does not conform to any of these subtypes, and is also not considered unclassifiable, then it is classified as “diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified” (DLBCL, NOS). The majority of DLBCL cases fall into this category. Much research has been devoted to separating this still-heterogeneous group; such distinctions are usually made along lines of cellular morphology, gene expression, and immunohistochemical properties.

Morphology

Within cellular morphology, three variants are most commonly seen: centroblastic, immunoblastic, and anaplastic.

Most cases of DLBCL are centroblastic, having the appearance of medium-to-large-sized lymphocytes with scanty cytoplasm. Oval or round nuclei containing fine chromatin are prominently visible, having two to four nucleoli within each nucleus. Sometimes the tumor may be monomorphic, composed almost entirely of centroblasts. However, most cases are polymorphic, with a mixture of centroblastic and immunoblastic cells.[18]

Immunoblasts have significant basophilic cytoplasm and a central nucleolus. A tumor can be classified as immunoblastic if greater than 90% of its cells are immunoblasts.[18]This distinction can be problematic, however, because hematopathologists reviewing the microscope slides may often disagree on whether a collection of cells is best characterized as centroblasts or immunoblasts.[19] Such disagreement indicates poor inter-rater reliability.

The third morphologic variant, anaplastic, consists of tumor cells which appear very differently from their normal B cell counterparts. The cells are generally very large with a round, oval, or polygonal shape and pleomorphic nuclei, and may resemble Reed–Sternberg cells.

Gene and microRNA expression

Gene expression profiling studies have also attempted to distinguish heterogeneous groups of DLBCL from each other. These studies examine thousands of genes simultaneously using a DNA microarray, looking for patterns which may help in grouping cases of DLBCL. As originally discovered by Ash Alizadeh and colleagues[15], many studies now suggest that cases of DLBCL, NOS can be separated into two groups on the basis of their gene expression profiles; these groups are known as germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) and activated B-cell-like (ABC).[15][20][21][22] Tumor cells in the germinal center B-cell-like subgroup resemble normal B cells in the germinal center closely, and are generally associated with a favorable prognosis.[23][24] Activated B-cell-like tumor cells are associated with a poorer prognosis,[24] and derive their name from studies which show the continuous activation of certain pathways normally activated when B cells interact with an antigen. The NF-κB pathway, which is normally involved in transforming B cells into plasma cells, is an important example of one such pathway.[25].

Another notable finding of recent gene expression studies is the importance of the cells and microscopic structures interspersed between the malignant B cells within the DLBCL tumor, an area commonly known as the tumor microenvironment. The presence of gene expression signatures commonly associated with macrophages, T cells, and remodelling of the extracellular matrix seems to be associated with an improved prognosis and better overall survival.[24][26] Alternatively, expression of genes coding for pro-angiogenic factors is correlated with poorer survival.[24]

Immunohistochemistry

With the apparent success of gene expression profiling in separating biologically distinct cases of DLBCL, NOS, some researchers examined whether a similar distinction could be made using immunohistochemical staining (IHC), a widely used method for characterizing tissue samples. This technique uses highly specific antibody-based stains to detect proteins on a microscope slide, and since microarrays are not widely available for routine clinical use, IHC is a desirable alternative.[27][28] Many of these studies focused on stains against the products of prognostically significant genes which had been implicated in DLBCL gene expression studies. Examples of such genes include BCL2, BCL6, MUM1, LMO2, MYC, and p21. Several algorithms for separating DLBCL cases by IHC arose out of this research, categorizing tissue samples into groups most commonly known as GCB and non-GCB.[28][29][30][31] The correlation between these GCB/non-GCB immunohistochemical groupings and the GCB/ABC groupings used in gene expression profiling studies is uncertain,[23][30] as is their prognostic value.[23] This uncertainty may arise in part due to poor inter-rater reliability in performing common immunohistochemical stains.[27]

Association with EBV

About 10–15% percent of DLBCL cases are associated with the Epstein–Barr virus. These cases are now diagnosed as having Epstein–Barr virus-positive (EBV+) diffuse large B cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (EBV+ DLBCL), a disease classified as one form of the Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative diseases. EBV+ DLBCL is distinguished from EBV-negative DLBCL in that virtually all the large B cells in the malignant tissue infiltrates are EBV+ and express various EBV genes.[32] The large B cells in EBV+ DLBCL are centroblastic (i.e. activated) B-cells[33] that express protein products made by the EBV which infect them. These proteins include the EBERs,[32] LMP1, EBNA1, and EBNA2.[34] They may be responsible for activating their infected cells' NF-kB, STAT/JAK, NOD-like receptor, and Toll-like receptor cell signaling pathways and thereby promoting the proliferation and survival of these cells.[34]

Treatment

Chemotherapy

Current treatment typically includes R-CHOP, which consists of the traditional CHOP, to which rituximab has been added.[35][36] This regimen has increased the rate of complete response for DLBCL patients, particularly in elderly patients.[37] R-CHOP is a combination of one monoclonal antibody (rituximab), three chemotherapy agents (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine), and one steroid (prednisone).[38] These medications are administered intravenously, and the regimen is most effective when it is administered multiple times over a period of months. People often receive this type of chemotherapy through a PICC line (peripherally inserted central catheter) in their arm near the elbow or a surgically implanted venous access port. The number of cycles of chemotherapy given depends on the stage of the disease — patients with limited disease typically receive three cycles of chemotherapy, while patients with extensive disease may need to undergo six to eight cycles. A recent approach involves obtaining a PET scan after the completion of two cycles of chemotherapy, to assist the treatment team in making further decisions about the future course of treatment. Older people often have more difficulty tolerating therapy than younger people. Lower intensity regimens have been attempted in this age group.[39]

A second regimen evaluated was R-EPOCH (rituximab with etoposide-prednisone-vincristine-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide) which had demonstrated a 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 79% in a phase II trial. However a phase III trial, CALGB 50303, compared R-EPOCH with R-CHOP in patients with newly diagnosed DLBCL,[40] found no difference in survival rates but found R-EPOCH had a higher level of hematologic toxicity.[41]

One area of active research is on separating patients into groups based on their prognosis and how likely they are to benefit from different drugs. Methods like gene expression profiling and next-generation sequencing may result in more effective and more personalized treatment.[42][43]

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is often part of the treatment for DLBCL. It is commonly used after the completion of chemotherapy. Radiation therapy alone is not an effective treatment for this disease.

Immunotherapy

On October 18, 2017, FDA granted approval to axicabtagene ciloleucel—adoptive cell transfer therapy for DLBCL treatment.[44]

Prognosis

The germinal center subtype has the best prognosis,[37] with 66.6% of treated patients surviving more than five years. The IPI score is used in prognosis in clinical practice.[45] Lenalidomide has been recently shown to improve outcomes in the non-germinal center subtype.[46] Ratios of immune effectors such as CD4 and CD8 to immune checkpoints such as PD-L1 and M2 macrophages are independent of and additive to the cell of origin and IPI in DLBCL, and are applicable to paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens. These findings might have potential implications for selection of patients for checkpoint blockade and/or lenalidomide within clinical trials.[47]

For children with diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, most studies have found 5-year survival rates ranging from about 70% to more than 90%.[48]

Recent studies

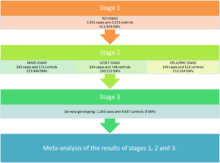

James Cerhan and colleagues,[49] try to determine genetic susceptibility that exists for this cancer by meta-analysis of three genome-wide association studies (GWAS). For this, a total of 3,857 cases and 7,666 controls were analyzed. This study is divided into three stages, which can differentiate into two phases:[49]

– Discovery Phase: Stages 1 and 2.

– Phase replication: Stage 3.

Stage 1

At this early stage, to study the genetic susceptibility, a GWAS with DLBCL cases and controls of European ancestry from 22 studies of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) was performed. To determine the subtype of NHL, hierarchical classification proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) was used. All cases of DLBCL with enough DNA and a subset of controls, matched for age and sex, along with 4% duplicates were genotyped. They were selected in this stage 611.844 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) that exceeded the quality criteria, genomic significance values, alignment and other statistical values.

Stage 2

At this stage the data of three independent previous GWAS, including two unpublished so far (GELA/EPIC and May) and one already published (USCF), with a total of 1,196 cases and 1,445 controls. The analysis was restricted to common SNPs on the basis of the 1000 Genomes Project version 3 because the data used were from different platforms. The criteria of quality control for these studies were adjusted to analyze all cases under the same conditions. In the meta-analysis of all SNPs of steps 1 and 2, 19 significant SNPs were identified, and 134 with a suggestive level of significance; 123 of the total were located in the HLA region on chromosome 6.

Stage 3

In the last stage, replication studies and technical validation were performed. The genotyping of 8 SNPs de novo was performed in the most significant HLA loci outside the region and one within it.

Results

As a result of this study, five SNPs were obtained in four loci significantly associated with the disease, which may be related to the following genes: EXOC2, PVT1, NCOA1 and HLA-B.

- EXOC2: This gene is near to the locus rs116446171 located in the region 6p25.3, in the same haplotype. This gene encodes a protein that forms part of a large multiprotein complex responsible for vesicle trafficking and the maintenance. This protein plays an important role in the maintenance of epithelial cell polarity, cell motility, cytokinesis, proliferation and metastasis, which plays a crucial role in carcinogenic processes.

- PVT1: This study has linked two variants for 8q24.21 locus (rs13255292 and rs4736601). This region gives rise to an antisense RNA, involved in the activation of MYC. The proximity of PVT1 and MYC oncogene, which is known to be deregulated in some DLBCLs suggests that germline variation in this region may also contribute to the risk of developing the disease.

- COA1: The SNP rs79480871 located in 2p13.3 as susceptibility locus was identified near NCOA1. It is a coactivator for steroid hormones, and the synthesized protein is involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. But the connection between the SNP and NCOA1 gene was not clear, because this polymorphism doesn't belong to the same haplotype, so a further study of this region is required.

- HLA-B: The strongest association in the HLA region was with HLA-B, the SNP rs2523607 and allele HLA-B08: 01, with a very high value linkage. HLA-B encodes a heavy chain of HLA class I, that heterodimerizes with a light chain. The HLA class I has a central role in the presentation of self or foreign antigens, processed intracellularly, to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. HLA molecules of class I have been associated with many diseases and cancers of the immune system. The results suggest a possible association of other loci within the HLA region with this disease, but further study is needed to evaluate this possibility.

See also

- Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma—a subgroup of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising in the mediastinum of young adults[50]

- Germinal center B-cell like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma—a subgroup of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma which seem to arise from normal germinal center B-cells[22]

Footnotes

- "A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project". Blood. 89 (11): 3909–18. 1997. doi:10.1182/blood.V89.11.3909. PMID 9166827.

- Morton, LM; Wang, SS; Devesa, SS; Hartge, P; Weisenburger, DD; Linet, MS (2006). "Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001". Blood. 107 (1): 265–76. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-06-2508. PMC 1895348. PMID 16150940.

- Smith, A; Howell, D; Patmore, R; Jack, A; Roman, E (2011). "Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: A report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network". British Journal of Cancer. 105 (11): 1684–92. doi:10.1038/bjc.2011.450. PMC 3242607. PMID 22045184.

- Smith, A; Roman, E; Howell, D; Jones, R; Patmore, R; Jack, A; Haematological Malignancy Research Network (2010). "The Haematological Malignancy Research Network (HMRN): A new information strategy for population based epidemiology and health service research". British Journal of Haematology. 148 (5): 739–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08010.x. PMC 3066245. PMID 19958356.

- Kumar, V; Abbas, AK; Fausto, N; Aster, JC (28 May 2009). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 607. ISBN 978-1-4377-2015-0.

- Freeman, AS; Aster, JC (2012). "Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathologic features, and diagnosis of diffuse large B cell lymphoma". In Basow, DS (ed.). UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate.

- Casulo C, Friedberg J (2017). "Transformation of marginal zone lymphoma (and association with other lymphomas)". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Haematology. 30 (1–2): 131–138. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2016.08.029. PMID 28288708.

- Swerdlow et al. 2008, p. 233.

- Swerdlow et al. 2008, p. 243.

- Goldman & Schafer 2012, p. 1222.

- Goldman & Schafer 2012, p. 1225.

- Akyurek, N; Uner, A; Benekli, M; Barista, I (2012). "Prognostic significance of MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 rearrangements in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone plus rituximab". Cancer. 118 (17): 4173–83. doi:10.1002/cncr.27396. PMID 22213394.

- Feugier, P; Van Hoof, A; Sebban, C; Solal-Celigny, P; Bouabdallah, R; Fermé, C; Christian, B; Lepage, E; Tilly, H; Morschhauser, F; Gaulard, P; Salles, G; Bosly, A; Gisselbrecht, C; Reyes, F; Coiffier, B (2005). "Long-Term Results of the R-CHOP Study in the Treatment of Elderly Patients with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (18): 4117–26. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.09.131. PMID 15867204.

- Cultrera, J L; Dalia, SM (2012). "Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Current strategies and future directions" (PDF). Cancer Control. 19 (3): 204–13. doi:10.1177/107327481201900305. PMID 22710896.

- Alizadeh, AA; Eisen, MB; Davis, RE; Ma, C; Lossos, IS; Rosenwald, A; Boldrick, JC; Sabet, H; Tran, T; Yu, X; Powell, JI; Yang, L; Marti, GE; Moore, T; Hudson, J; Lu, Lisheng; Lewis, David B; Tibshirani, R; Sherlock, G; Chan, WC; Greiner, TC; Weisenburger, DD; Armitage, JO; Warnke, R; Levy, R; Wilson, W; Grever, MR; Byrd, JC; Botstein, D; et al. (2000). "Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling". Nature. 403 (6769): 503–11. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..503A. doi:10.1038/35000501. PMID 10676951.

- Swerdlow et al. 2008, pp. 233–7.

- Swerdlow et al. 2008, pp. 250–1.

- Swerdlow et al. 2008, p. 234.

- Harris, NL; Jaffe, ES; Stein, H; Banks, PM; Chan, JK; Cleary, ML; Delsol, G; De Wolf-Peeters, C; Falini, B; Gatter, KC (1994). "A revised European–American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: A proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group". Blood. 84 (5): 1361–92. doi:10.1182/blood.V84.5.1361.1361. PMID 8068936.

- Shipp, MA; Ross, KN; Tamayo, Pablo; Weng, AP; Kutok, JL; Aguiar, RCT; Gaasenbeek, M; Angelo, Michael; Reich, M; Pinkus, GS; Ray, TS; Koval, MA; Last, KW; Norton, A; Lister, TA; Mesirov, J; Neuberg, DS; Lander, ES; Aster, JC; Golub, TR (2002). "Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction by gene-expression profiling and supervised machine learning". Nature Medicine. 8 (1): 68–74. doi:10.1038/nm0102-68. PMID 11786909.

- Rosenwald, A; Wright, G; Chan, WC; Connors, JM; Campo, E; Fisher, RI; Gascoyne, RD; Muller-Hermelink, HK; Smeland, EB; Giltnane, JM; Hurt, EM; Zhao, H; Averett, L; Yang, L; Wilson, WH; Jaffe, ES; Simon, R; Klausner, RD; Powell, J; Duffey, PL; Longo, DL; Greiner, TC; Weisenburger, DD; Sanger, WG; Dave, BJ; Lynch, JC; Vose, J; Armitage, JO; Montserrat, E; et al. (2002). "The Use of Molecular Profiling to Predict Survival after Chemotherapy for Diffuse Large-B-Cell Lymphoma". New England Journal of Medicine. 346 (25): 1937–47. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa012914. PMID 12075054.

- Wright, G; Tan, B; Rosenwald, A; Hurt, EH; Wiestner, A; Staudt, LM (2003). "A gene expression-based method to diagnose clinically distinct subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (17): 9991–6. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.9991W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1732008100. JSTOR 3147650. PMC 187912. PMID 12900505.

- Gutierrez-Garcia, G; Cardesa-Salzmann, T; Climent, F; Gonzalez-Barca, E; Mercadal, S; Mate, JL; Sancho, J. M; Arenillas, L; Serrano, S; Escoda, L; Martinez, S; Valera, A; Martinez, A; Jares, P; Pinyol, M; Garcia-Herrera, A; Martinez-Trillos, A; Gine, E; Villamor, N; Campo, E; Colomo, L; Lopez-Guillermo, A; Grup per l'Estudi dels Limfomes de Catalunya I Balears (GELCAB) (2011). "Gene-expression profiling and not immunophenotypic algorithms predicts prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy". Blood. 117 (18): 4836–43. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-12-322362. PMID 21441466.

- Lenz, G; Wright, G; Dave, SS; Xiao, W; Powell, J; Zhao, H; Xu, W; Tan, B; Goldschmidt, N; Iqbal, J; Vose, J; Bast, M; Fu, K; Weisenburger, DD; Greiner, TC; Armitage, JO; Kyle, A; May, L; Gascoyne, RD; Connors, JM; Troen, G; Holte, H; Kvaloy, S; Dierickx, D; Verhoef, G; Delabie, J; Smeland, EB; Jares, P; Martinez, A; et al. (2008). "Stromal Gene Signatures in Large-B-Cell Lymphomas". New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (22): 2313–23. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802885. PMID 19038878.

- Schwartz, RS; Lenz, G; Staudt, LM (2010). "Aggressive Lymphomas". New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (15): 1417–29. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0807082. PMID 20393178.

- Linderoth, J; Edén, P; Ehinger, M; Valcich, J; Jerkeman, M; Bendahl, PO; Berglund, M; Enblad, G; Erlanson, M; Roos, G; Cavallin-Ståhl, E (2008). "Genes associated with the tumour microenvironment are differentially expressed in cured versus primary chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma". British Journal of Haematology. 141 (4): 423–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07037.x. PMID 18419622.

- De Jong, D; Xie, W; Rosenwald, A; Chhanabhai, M; Gaulard, P; Klapper, W; Lee, A; Sander, B; Thorns, C; Campo, E; Molina, T; Hagenbeek, A; Horning, S; Lister, A; Raemaekers, J; Salles, G; Gascoyne, RD; Weller, E (2008). "Retracted: Immunohistochemical prognostic markers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Validation of tissue microarray as a prerequisite for broad clinical applications (a study from the Lunenburg Lymphoma Biomarker Consortium)". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 62 (2): 128–38. doi:10.1136/jcp.2008.057257. PMID 18794197.

- Choi, WWL; Weisenburger, DD; Greiner, TC; Piris, M A; Banham, AH; Delabie, J; Braziel, RM; Geng, H; Iqbal, J; Lenz, G; Vose, JM; Hans, CP; Fu, K; Smith, LM; Li, M; Liu, Z; Gascoyne, RD; Rosenwald, A; Ott, G; Rimsza, LM; Campo, E; Jaffe, ES; Jaye, DL; Staudt, LM; Chan, WC (2009). "A New Immunostain Algorithm Classifies Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma into Molecular Subtypes with High Accuracy". Clinical Cancer Research. 15 (17): 5494–502. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0113. PMID 19706817.

- Colomo, L; López-Guillermo, A; Perales, M; Rives, S; Martínez, A; Bosch, F; Colomer, D; Falini, B; Montserrat, E; Campo, E (2002). "Clinical impact of the differentiation profile assessed by immunophenotyping in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma". Blood. 101 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-04-1286. PMID 12393466.

- Hans, CP; Weisenburger, DD; Greiner, TC; Gascoyne, R D; Delabie, J; Ott, G; Müller-Hermelink, HK; Campo, E; Braziel, RM; Jaffe, E. S; Pan, Z; Farinha, P; Smith, L. M; Falini, B; Banham, AH; Rosenwald, A; Staudt, LM; Connors, JM; Armitage, JO; Chan, WC (2004). "Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray". Blood. 103 (1): 275–82. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545. PMID 14504078.

- Muris, JJF; Meijer, C; Vos, W; Van Krieken, J; Jiwa, NM; Ossenkoppele, GJ; Oudejans, JJ (2006). "Immunohistochemical profiling based on Bcl-2, CD10 and MUM1 expression improves risk stratification in patients with primary nodal diffuse large B cell lymphoma". The Journal of Pathology. 208 (5): 714–23. doi:10.1002/path.1924. PMID 16400625.

- Vockerodt M, Yap LF, Shannon-Lowe C, Curley H, Wei W, Vrzalikova K, Murray PG (January 2015). "The Epstein–Barr virus and the pathogenesis of lymphoma". The Journal of Pathology. 235 (2): 312–22. doi:10.1002/path.4459. PMID 25294567.

- Farrell PJ (August 2018). "Epstein-Barr Virus and Cancer". Annual Review of Pathology. 14: 29–53. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-013023. PMID 30125149.

- Rezk SA, Zhao X, Weiss LM (September 2018). "Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphoid proliferations, a 2018 update". Human Pathology. 79: 18–41. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2018.05.020. PMID 29885408.

- "DLBCL".

- Sehn, LH; Berry, B; Chhanabhai, M; Fitzgerald, C; Gill, K; Hoskins, P; Klasa, R; Savage, K J; Shenkier, T; Sutherland, J; Gascoyne, RD; Connors, JM (2007). "The revised International Prognostic Index (R-IPI) is a better predictor of outcome than the standard International Prognostic Index (IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP". Blood. 109 (5): 1857–61. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-08-038257. PMID 17105812.

- Turgeon 2005, pp. 285–6.

- Farber, CM; Axelrod, RC (2011). "The Clinical and Economic Value of Rituximab for the Treatment of Hematologic Malignancies". Contemporary Oncology. 3 (1).

- Zaja, F; Tomadini, V; Zaccaria, A; Lenoci, M; Battista, M; Molinari, A L; Fabbri, A; Battista, R; Cabras, MG; Gallamini, A; Fanin, R (2006). "CHOP-rituximab with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 47 (10): 2174–80. doi:10.1080/10428190600799946. PMID 17071492.

- Peck, Susan R. (April 19, 2012) Beyond R-CHOP-21: What's New in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma OncLive

- Starr, Phoebe (February 2017). "R-CHOP Prevails Over Dose-Adjusted EPOCH-R as Standard of Care for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma". The Journal of Hematology Oncology Pharmacy.

- Sehn, LH (2012). "Paramount prognostic factors that guide therapeutic strategies in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma". Hematology. 2012: 402–9. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.402 (inactive 2019-11-20). PMID 23233611.

- Barton, S; Hawkes, EA; Wotherspoon, A; Cunningham, D (2012). "Are We Ready to Stratify Treatment for Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Using Molecular Hallmarks?". The Oncologist. 17 (12): 1562–73. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0218. PMC 3528389. PMID 23086691.

- Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and. "Approved Drugs—FDA approves axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project (1993). "A Predictive Model for Aggressive Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma". New England Journal of Medicine. 329 (14): 987–94. doi:10.1056/NEJM199309303291402. PMID 8141877.

- Nowakowski, GS; Laplant, B; Macon, WR; Reeder, CB; Foran, JM; Nelson, GD; Thompson, CA; Rivera, CE; Inwards, DJ; Micallef, IN; Johnston, PB; Porrata, LF; Ansell, SM; Gascoyne, R D; Habermann, TM; Witzig, TE (2014). "Lenalidomide Combined with R-CHOP Overcomes Negative Prognostic Impact of Non-Germinal Center B-Cell Phenotype in Newly Diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Phase II Study". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 33 (3): 251–7. doi:10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5714. PMID 25135992.

- Keane, C; Vari, F; Hertzberg, M; LC, KA; Green, MR; Han, E; Seymour, JF; Hicks, RJ; Gill, D; Crooks, P; Gould, C; Jones, K; Griffiths, LR; Talaulikar, D; Jain, S; Tobin, J; Gandhi, MK (2015). "Ratios of T-cell immune effectors and checkpoint molecules as prognostic biomarkers in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a population-based study" (PDF). Lancet Haematology. 2 (10): e445–55. doi:10.1016/s2352-3026(15)00150-7. PMID 26686046.

- "Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in Children | Lymphoma in Children".

- Cerhan, JR; Berndt, SI; Vijai, J; Ghesquières, H; McKay, J; Wang, SS; Wang, Z; Yeager, M; Conde, L; De Bakker, PIW; Nieters, A; Cox, D; Burdett, L; Monnereau, A; Flowers, CR; De Roos, AJ; Brooks-Wilson, AR; Lan, Q; Severi, G; Melbye, M; Gu, J; Jackson, RD; Kane, E; Teras, LR; Purdue, MP; Vajdic, CM; Spinelli, JJ; Giles, GG; Albanes, D; et al. (2014). "Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for diffuse large B cell lymphoma". Nature Genetics. 46 (11): 1233–8. doi:10.1038/ng.3105. PMC 4213349. PMID 25261932.

- Swerdlow et al. 2008, p. 250.

Sources

- Swerdlow, SH; Campo, E; Jaffe, ES; et al., eds. (2008). WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC. ISBN 978-92-832-2431-0.

- Goldman, L; Schafer, AI (2012). Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). ISBN 978-1-4377-1604-7.

- Turgeon, ML (2005). Clinical hematology: theory and procedures. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-5007-3.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |