Haemophilus influenzae type b

On this Page

Haemophilus influenzae type b

- Severe bacterial infection, particularly among infants

- During late 19th century believed to cause influenza

- Immunology and microbiology clarified in 1930s

Haemophilus influenzae is a cause of bacterial infections that are often severe, particularly among infants. It was first described by Pfeiffer in 1892. During an outbreak of influenza he found the bacteria in sputum of patients and proposed a causal association between this bacterium and the clinical syndrome known as influenza. The organism was given the name Haemophilus by Winslow, et al. in 1920. It was not until 1933 that Smith, et al. established that influenza was caused by a virus and that H. influenzae was a cause of secondary infection.

In the 1930s, Margaret Pittman demonstrated that H. influenzae could be isolated in encapsulated and unencapsulated forms. She identified six capsular types (a-f), and observed that virtually all isolates from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood were of the capsular type b.

Before the introduction of effective vaccines, H. influenzae type b (Hib) was the leading cause of bacterial meningitis and other invasive bacterial disease among children younger than 5 years of age; approximately one in 200 children in this age group developed invasive Hib disease. Nearly all Hib infections occurred among children younger than 5 years of age, and approximately two-thirds of all cases occurred among children younger than 18 months of age.

Haemophilus influenzae

Haemophilus influenzae

- Aerobic gram-negative bacteria

- Polysaccharide capsule

- Six different serotypes (a-f) of polysaccharide capsule

- 95% of invasive disease caused by type b (prevaccine)

Haemophilus influenzae is a gram-negative coccobacillus. It is generally aerobic but can grow as a facultative anaerobe. In vitro growth requires accessory growth factors, including “X” factor (hemin) and “V” factor (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide [NAD]).

Chocolate agar media are used for isolation. H. influenzae will generally not grow on blood agar, which lacks NAD.

H. influenzae has encapsulated (typeable) and unencapsulated nontypeable strains. The outermost structure of encapsulated H. influenzae is composed of polyribosyl-ribitol-phosphate (PRP), a polysaccharide that is responsible for virulence and immunity. Six antigenically and biochemically distinct capsular polysaccharide serotypes have been described; these are designated types a through f. There are currently no vaccines to prevent disease caused by non-b encapsulated or nontypeable strains. In the prevaccine era, type b organisms accounted for 95% of all strains that caused invasive disease.

Pathogenesis

Haemophilus influenzae type b Pathogenesis

- Organism colonizes nasopharynx

- In some persons organism invades bloodstream and causes infection at distant site

- Antecedent upper respiratory tract infection may be a contributing factor

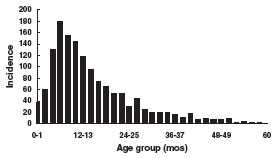

Haemophilus influenzae type b 1986 Incidence* by Age Group

*Rate per 100,000 population, prevaccine era

The organism enters the body through the nasopharynx. Organisms colonize the nasopharynx and may remain only transiently or for several months in the absence of symptoms (asymptomatic carrier). In the prevaccine era, Hib could be isolated from the nasopharynx of 0.5%-3% of normal infants and children but was not common in adults. Nontypeable (unencapsulated) strains are also frequent inhabitants of the human respiratory tract.

In some persons, the organism causes an invasive infection. The exact mode of invasion to the bloodstream is unknown. Antecedent viral or mycoplasma infection of the upper respiratory tract may be a contributing factor. The bacteria spread in the bloodstream to distant sites in the body. Meninges are especially likely to be affected.

Incidence is strikingly age-dependent. In the prevaccine era, up to 60% of invasive disease occurred before age 12 months, with a peak occurrence among children 6-11 months of age. Passive protection of some infants is provided by transplacentally acquired maternal IgG antibodies and breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life. Children 60 months of age and older account for less than 10% of invasive disease. The presumed reason for this age distribution is the acquisition of immunity to Hib with increasing age.

Antibodies to Hib capsular polysaccharide are protective. The precise level of antibody required for protection against invasive disease is not clearly established. However, a titer of 1 µg/mL 3 weeks postvaccination correlated with protection in studies following vaccination with unconjugated purified polyribosyl-ribitol-phosphate (PRP) vaccine and suggested long-term protection from invasive disease.

Acquisition of both anticapsular and serum bactericidal antibody is inversely related to the age-specific incidence of Hib disease.

In the prevaccine era, most children acquired immunity by 5-6 years of age through asymptomatic infection by Hib bacteria. Since only a relatively small proportion of children carry Hib at any time, it has been postulated that exposure to organisms that share common antigenic structures with the capsule of Hib (so-called “cross-reacting organisms”) may also stimulate the development of anticapsular antibodies against Hib. Natural exposure to Hib also induces antibodies to outer membrane proteins, lipopolysaccharides, and other antigens on the surface of the bacterium.

The genetic constitution of the host may also be important in susceptibility to infection with Hib. Risk for Hib disease has been associated with a number of genetic markers, but the mechanism of these associations is unknown. No single genetic relationship regulating susceptibility or immune responses to polysaccharide antigens has yet been convincingly demonstrated.

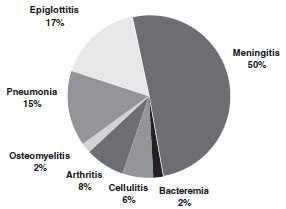

Haemophilus influenzae type b Clinical Features*

*prevaccine era

Haemophilus influenzae type b Meningitis

- Accounted for approximately 50%-65% of cases in the prevaccine era

- Hearing impairment or neurologic sequelae in 15%-30%

- Case-fatality rate 3%-6% despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy

Clinical Features

Invasive disease caused by H. influenzae type b can affect many organ systems. The most common types of invasive disease are meningitis, epiglottitis, pneumonia, arthritis, and cellulitis.

Meningitis is infection of the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord and is the most common clinical manifestation of invasive Hib disease, accounting for 50%-65% of cases in the prevaccine era. Hallmarks of Hib meningitis are fever, decreased mental status, and stiff neck (these symptoms also occur with meningitis caused by other bacteria). Hearing impairment or other neurologic sequelae occur in 15%-30% of survivors. The case-fatality rate is 3%-6%, despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

Epiglottitis is an infection and swelling of the epiglottis, the tissue in the throat that covers and protects the larynx during swallowing. Epiglottitis may cause life-threatening airway obstruction.

Septic arthritis (joint infection), cellulitis (rapidly progressing skin infection which usually involves face, head, or neck), and pneumonia (which can be mild focal or severe empyema) are common manifestations of invasive disease. Osteomyelitis (bone infection) and pericarditis (infection of the sac covering the heart) are less common forms of invasive disease.

Otitis media and acute bronchitis due to H. influenzae are generally caused by nontypeable strains. Hib strains account for only 5%-10% of H. influenzae causing otitis media.

Non-type b encapsulated strains can cause invasive disease similar to type b infections. Nontypeable (unencapsulated) strains may cause invasive disease but are generally less virulent than encapsulated strains. Nontypeable strains are rare causes of serious infection among children but are a common cause of ear infections in children and bronchitis in adults.

Laboratory Diagnosis

A Gram stain of an infected body fluid may demonstrate small gram-negative coccobacilli suggestive of invasive Haemophilus disease. CSF, blood, pleural fluid, joint fluid, and middle ear aspirates should be cultured on appropriate media. A positive culture for H. influenzae (Hi) establishes the diagnosis.

All isolates of H. influenzae should be serotyped. This is an extremely important laboratory procedure that should be performed on every isolate of H. influenzae, especially those obtained from children younger than 15 years of age. Two tests are available for serotyping Hi isolates: slide agglutination and serotype-specific real-time PCR. These tests determine whether an isolate is type b, which is the only type that is potentially vaccine preventable. Serotyping is usually done by either a state health department laboratory or a reference laboratory. State health departments with questions about serotyping should contact the CDC Meningitis and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Branch Laboratory at 404-639-3158.

Detection of antigen or DNA may be used as an adjunct to culture, particularly in diagnosing H. influenzae infection in patients who have been partially treated with antimicrobial agents, in which case the organism may not be viable on culture. Slide agglutination is used to detect Hib capsular polysaccharide antigen in CSF, but a negative test does not exclude the diagnosis, and false-positive tests have been reported. Antigen testing of serum and urine is not recommended because of false positives. Furthermore, no slide agglutination assay is available to identify non-b Hi serotypes. Serotype-specific real-time PCR is currently available to detect the specific target gene of each H. influenzae serotype and can be used for detection of H. influenzae in blood, CSF, or other clinical specimens.

Haemophilus influenzae type b Medical Management

- Hospitalization required

- Treatment with an effective 3rd generation cephalosporin, or chloramphenicol plus ampicillin

- Ampicillin-resistant strains now common throughout the United States

Medical Management

Hospitalization is generally required for invasive Hib disease. Antimicrobial therapy with an effective third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime or ceftriaxone), or chloramphenicol in combination with ampicillin should be begun immediately. The treatment course is usually 10 days. Ampicillin-resistant strains of Hib are now common throughout the United States. Children with life-threatening illness in which Hib may be the etiologic agent should not receive ampicillin alone as initial empiric therapy.

Epidemiology

Occurrence

Hib disease occurs worldwide.

Haemophilus influenzae type b Epidemiology

- Reservoir

- human

- asymptomatic carriers

- human

- Transmission

- neonates

- aspiration of amniotic fluid

- genital track secretions during delivery

- respiratory droplets

- neonates

- Temporal pattern

- peaks in Sept-Dec and March-May

- Communicability

- generally limited but higher in some circumstances

Reservoir

Humans (asymptomatic carriers) are the only known reservoir. Hib does not survive in the environment on inanimate surfaces.

Transmission

The primary mode of Hib transmission is presumably by respiratory droplet spread, although firm evidence for this mechanism is lacking. Neonates can acquire infection by aspiration of amniotic fluid or contact with genital tract secretions during delivery.

Temporal Pattern

Several studies in the prevaccine era described a bimodal seasonal pattern in the United States, with one peak during September through December and a second peak during March through May. The reason for this bimodal pattern is not known.

Communicability

The contagious potential of invasive Hib disease is considered to be limited. However, certain circumstances, particularly close contact with a case-patient (e.g., household, child care, or institutional setting) can lead to outbreaks or direct secondary transmission of the disease.

Secular Trends in the United States

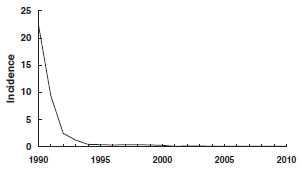

Incidence* of Invasive Hib Disease, 1990-2010

*rate per 100,000 children <5 years of age

Haemophilus influenzae - United States, 2003-2010

- Average of 2,562 infections per year reported to CDC in all age groups

- of these, 398 (16%) were children younger than 5 years

H. influenzae infections became nationally reportable in 1991. Serotype-specific reporting continues to be incomplete.

Before the availability of national reporting data, several areas conducted active surveillance for H. influenzae disease, which allowed estimates of disease nationwide. In the early 1980s, it was estimated that about 20,000 cases occurred annually in the United States, primarily among children younger than 5 years of age (40-50 cases per 100,000 population). The incidence of invasive Hib disease began to decline dramatically in the late 1980s, coincident with licensure of conjugate Hib vaccines, and has declined by more than 99% compared with the prevaccine era.

From 2003 through 2010, an average of 2,562 invasive H. influenzae infections per year were reported to CDC in all age groups (range 2,013-3,151 per year). Of these, an average of 398 (approximately 16%) per year were among children younger than 5 years of age. Serotype was known for 52% of the invasive cases in this age group. Two-hundred-two (average of 25 cases per year) were due to type b. In 2011, among children younger than 5 years of age, 14 cases of invasive disease due to Hib were reported in the United States. An additional 13 cases of Hib are estimated to have occurred among the 226 reports of invasive H. influenzae infections with an unknown serotype.

During 2010-2011, 33% of children younger than 5 years of age with confirmed invasive Hib disease were younger than 6 months of age and too young to have completed a three-dose primary vaccination series. Sixty-seven percent were age 6 months or older and were eligible to have completed the primary vaccination series. Of these age-eligible children, 64% were either unvaccinated, incompletely vaccinated (fewer than 3 doses), or their vaccination status was unknown. Thirty-six percent of children aged 6-59 months with confirmed type b disease had received three or more doses of Hib vaccine, including 5 who had received a booster dose 14 or more days before onset of their illness. The cause of Hib vaccine failure in these children is not known.

Haemophilus influenzae type b Risk Factors for Invasive Disease

- Exposure factors

- household crowding

- large household size

- child care attendance

- low socioeconomic status

- low parental education

- school-aged siblings

- Host factors

- race/ethnicity

- chronic disease

- possibly gender (risk higher for males)

Risk factors for Hib disease include exposure factors and host factors that increase the likelihood of exposure to Hib. Exposure factors include household crowding, large household size, child care attendance, low socioeconomic status, low parental education levels, and school-aged siblings. Host factors include race/ethnicity (elevated risk among Hispanics and Native Americans—possibly confounded by socioeconomic variables that are associated with both race/ethnicity and Hib disease), chronic disease (e.g., sickle cell anemia, antibody deficiency syndromes, malignancies - especially during chemotherapy), and possibly gender (risk is higher for males).

Protective factors (effect limited to infants younger than 6 months of age) include breastfeeding and passively acquired maternal antibody.

Secondary Hib disease is defined as illness occurring 1-60 days following contact with an ill child, and accounts for less than 5% of all invasive Hib disease. Among household contacts, six studies have found a secondary attack rate of 0.3% in the month following onset of the index case, which is about 600-fold higher than the risk for the general population. Attack rates varied substantially with age, from 3.7% among children 2 years of age and younger to 0% among contacts 6 years of age and older. In these household contacts, 64% of secondary cases occurred within the first week (excluding the first 24 hours) of disease onset in the index patient, 20% during the second week, and 16% during the third and fourth weeks.

Data are conflicting regarding the risk of secondary transmission among child care contacts. Secondary attack rates have varied from 0% to as high as 2.7%. Most studies seem to suggest that child care contacts are at relatively low risk for secondary transmission of Hib disease particularly if contacts are age-appropriately vaccinated.

Haemophilus influenzae type b Vaccines

Haemophilus influenzae type b Polysaccharide Vaccine

- Available 1985-1988

- Not effective in children younger than 18 months of age

- Efficacy in older children varied

Polysaccharide Vaccines

- Age-dependent immune response

- Not consistently immunogenic in children 2 years of age and younger

- No booster response

Polysaccharide Conjugate Vaccines

- Stimulates T-dependent immunity

- Enhanced antibody production, especially in young children

- Repeat doses elicit booster response

Characteristics

A pure polysaccharide vaccine (HbPV) was licensed in the United States in 1985. The vaccine was not effective in children younger than 18 months of age. Estimates of efficacy in older children varied widely, from 88% to -69% (a negative efficacy implies greater disease risk for vaccinees than nonvaccinees). HbPV was used until 1988 but is no longer available in the United States.

The characteristics of the Hib polysaccharide were similar to other polysaccharide vaccines (e.g., pneumococcal, meningococcal). The response to the vaccine was typical of a T-independent antigen, most notably an age-dependent immune response, and poor immunogenicity in children 2 years of age and younger. In addition, no boost in antibody titer was observed with repeated doses, the antibody that was produced was relatively low-affinity IgM, and switching to IgG production was minimal.

Haemophilus influenzae type b Polysaccharide-Protein Conjugate Vaccines

Conjugation is the process of chemically bonding a polysaccharide (a somewhat ineffective antigen) to a protein “carrier,” which is a more effective antigen. This process changes the polysaccharide from a T-independent to a T-dependent antigen and greatly improves immunogenicity, particularly in young children. In addition, repeat doses of conjugate vaccines elicit booster responses and allow maturation of class-specific immunity with predominance of IgG antibody. The conjugates also cause carrier priming and elicit antibody to “useful” carrier protein.

The first Hib conjugate vaccine (PRP-D, ProHIBIT) was licensed in December 1987. PRP-D is no longer available in the United States.

Three monovalent conjugate Hib vaccines are currently licensed and available for use. Two (ActHIB and PedvaxHIB) are licensed for use in infants as young as 6 weeks of age.

A third Hib vaccine (Hiberix) is approved only for the booster dose of the Hib schedule among children 12 months and older. The vaccines utilize different carrier proteins. Three combination vaccines that contain Hib conjugate vaccine are also available.

Hib Conjugate Vaccines

| PRP-T | ActHIB, Pentacel Hiberix (booster dose only) MenHibrix |

|---|---|

| PRP-OMP | PedvaxHIB, COMVAX |

HbOC (HibTiter) no longer available in the United States

Immunogenicity and Vaccine Efficacy

Hib conjugate vaccines licensed for use in infants are highly immunogenic. More than 95% of infants will develop protective antibody levels after a primary series. Clinical efficacy has been estimated at 95% to 100%. Invasive Hib disease in a completely vaccinated infant is not common.

Hib vaccine is immunogenic in patients with increased risk for invasive disease, such as those with sickle-cell disease, leukemia, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and those who have had a splenectomy. However, in persons with HIV infection, immunogenicity varies with stage of infection and degree of immunocompromise. Efficacy studies have not been performed in populations with increased risk of invasive disease.

Vaccination Schedule and Use

All infants, including those born preterm, should receive a primary series of conjugate Hib vaccine (separate or in combination), beginning at 2 months of age. The number of doses in the primary series depends on the type of vaccine used. A primary series of PRP-OMP (PedvaxHIB or COMVAX) vaccine is two doses; PRP-T (ActHIB, Pentacel, or MenHibrix) requires a three-dose primary series (see table below). A booster is recommended at 12-15 months regardless of which vaccine is used for the primary series.

ACIP-Recommended Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) Routine Vaccine Schedule

| Type | Vaccine | 2 months | 4 months | 6 months | 12-15 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRP-T | ActHIB | X (1st) | X (2nd) | X (3rd) | X |

| Pentacel* | X (1st) | X (2nd) | X (3rd) | X | |

| Hiberix† | — | — | — | X | |

| MenHibrix§ | X (1st) | X (2nd) | X (3rd) | X | |

| PRP-OMP | PedvaxHIB | X (1st) | X (2nd) | — | X |

| COMVAX | X (1st) | X (2nd) | — | X |

* The recommended age for the 4th dose of Pentacel is 15-18 months, but it can be given as early as 12 months, provided at least 6 months have elapsed since the 3rd dose.

† Hiberix is approved only for the last dose of the Hib series among children 12 months of age and older. The recommended age is 15 months, but to facilitate timely booster vaccination it may be given as early as 12 months.

§ The recommended age for the 4th dose of MenHibrix is 12-18 months.

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) Vaccine

- Recommended interval 8 weeks for primary series doses

- Minimum interval 4 weeks for primary series doses

- Vaccination at younger than 6 weeks of age may induce immunologic tolerance to subsequent doses of Hib vaccine

- Minimum age 6 weeks

The recommended interval between primary series doses is 8 weeks, with a minimum interval of 4 weeks. At least 8 weeks should separate the booster dose from the previous (second or third) dose. Hib vaccines may be given simultaneously with all other vaccines.

Limited data suggest that Hib conjugate vaccines given before 6 weeks of age may induce immunologic tolerance to subsequent doses of Hib vaccine. A dose given before 6 weeks of age may reduce the response to subsequent doses. As a result, Hib vaccines, including combination vaccines that contain Hib conjugate, should never be given to a child younger than 6 weeks of age.

With the exception of Hiberix, the monovalent conjugate Hib vaccines licensed for use in infants are interchangeable. A series that includes vaccine of more than one type will induce a protective antibody level. If a child receives different brands of Hib vaccine at 2 and 4 months of age, a third dose of either brand should be administered at 6 months of age to complete the primary series. Either vaccine may be used for the booster dose, regardless of what was administered in the primary series.

Unvaccinated children 7 months of age and older may not require a full series of three or four doses. The number of doses a child needs to complete the series depends on the child’s current age.

Haemophilus influenzae type b Vaccine Detailed Schedule for Unvaccinated Children

| Vaccine | Age at 1st Dose (months) | Primary series | Booster |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRP-T* | 2-6 | 3 doses, 8 weeks apart | 12-15 months |

| 7-11 | 2 doses, 4 weeks apart | 12-15 months | |

| 12-14 | 1 dose | 2 months later | |

| 15-59† | 1 dose | -- | |

| PRP-OMP | 2-6 | 2 doses, 8 weeks apart | 12-15 months |

| 7-11 | 2 doses, 4 weeks apart | 12-15 months | |

| 12-14 | 1 dose | 2 months later | |

| 15-59 | 1 dose | -- |

* Hiberix brand PRP-T vaccine is approved only for the last dose of the Hib series among children 12 months of age and older.

† MenHibrix brand PRP-T vaccine is not recommended for children 19 months of age or older.

Hib Vaccine Interchangeability

- Conjugate Hib vaccines licensed for the primary series* are interchangeable for primary series and booster dose

- 3 dose primary series if more than one brand of vaccine used

*ActHIB, Pedvax HIB, COMVAX, Pentacel, and MenHibrix

Unvaccinated Children 7 months of Age and Older

- Children starting late may not need entire 3 or 4 dose series

- Number of doses child requires depends on current age

Monovalent Vaccines

PRP-T (ActHIB)

Previously unvaccinated infants aged 2 through 6 months should receive three doses of vaccine administered 2 months apart, followed by a booster dose at age 12-15 months, administered at least 2 months after the last dose. A booster dose at 12-15 months of age is only needed if 2 or 3 primary doses were administered before age 12 months. Unvaccinated children aged 7 through 11 months should receive two doses of vaccine 4 weeks apart, followed by a booster dose at age 12-15 months, administered at least 2 months after the last dose. Unvaccinated children aged 12 through 14 months should receive one dose of vaccine followed by a booster at least 2 months later. Any previously unvaccinated child aged 15 through 59 months should receive a single dose of vaccine. PRP-T (ActHIB) must be reconstituted only with the 0.4% sodium chloride ActHIB diluent. If ActHIB diluent is not available then the provider must contact the manufacturer (Sanofi Pasteur) to obtain it. Any dose of ActHIB reconstituted with a diluent other than specific ActHIB diluent should not be counted as valid and must be repeated.

PRP-OMP (PedvaxHIB)

Hib Vaccine Following Invasive Disease

- Children younger than 24 months may not develop protective antibody after invasive disease

- Vaccinate during convalescence

- Administer a complete series for age

Hib Vaccine Use in Older Children and Adults

- Generally not recommended for persons older than 59 months of age

- 3 doses recommended for all persons who have received a hematopoietic cell transplant

- See the ACIP Hib vaccine statement for further details about vaccination in high-risk groups older than 59 months of age

*MMWR 2014; 63(No. RR-1):8

Unvaccinated children aged 2 through 6 months should receive two doses of vaccine 2 months apart, followed by a booster dose at 12-15 months of age, at least 2 months after the last dose. Unvaccinated children aged 7 through 11 months should receive two doses of vaccine 4 weeks apart, followed by a booster dose at age 12-15 months, administered at least 2 months after the last dose. Unvaccinated children aged 12 through 14 months should receive one dose of vaccine followed by a booster at least 2 months later. Any previously unvaccinated child 15 through 59 months of age should receive a single dose of vaccine.

Vaccination of Older Children and Adults and Special Populations

Children with a lapsed Hib immunization series (i.e., children who have received one or more doses of Hib-containing vaccine but are not up-to-date for their age) may not need all the remaining doses of a three- or four-dose series. Vaccination of children with a lapsed schedule is addressed in the catch-up schedule, published annually with the childhood vaccination schedule.

Hib invasive disease does not always result in development of protective anti-PRP antibody levels. Children younger than 24 months of age who develop invasive Hib disease should be considered susceptible and should receive Hib vaccine. Vaccination of these children should start as soon as possible during the convalescent phase of the illness. A complete series as recommended for the child’s age should be administered.

In general, Hib vaccination of persons older than 59 months of age is not recommended. The majority of older children are immune to Hib, probably from asymptomatic infection as infants. However, some older children and adults are at increased risk for invasive Hib disease and may be vaccinated if they were not vaccinated in childhood. These include those with functional or anatomic asplenia (e.g., sickle cell disease, postsplenectomy), immunodeficiency (in particular, persons with IgG2 subclass deficiency), early component complement deficiency, infection with HIV, and receipt of chemotherapy or radiation therapy for a malignant neoplasm. Patients undergoing elective splenectomy should receive one dose of Hib vaccine if unimmunized. Persons 15 months of age or older with functional or anatomic asplenia and HIV-infected children should receive at least one dose of Hib vaccine if unimmunized. Adults with HIV do not need a dose of Hib vaccine. Patients receiving hematopoietic cell transplants should receive 3 doses of Hib vaccine 1 month apart beginning 6-12 months post-transplant regardless of prior Hib vaccine history. Readers should review the ACIP Hib vaccine statement for further details about vaccination in high-risk groups.

For American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/AN), PRP-OMP is the preferred vaccine for the primary series doses. Hib meningitis incidence peaks at a younger age among AI/AN infants, and PRP-OMP vaccines produce a protective antibody response after the first dose and provide early protection that AI/AN infants particularly need.

Combination Vaccines

Combination Vaccines Containing Hib

- DTaP-IPV/Hib

- Pentacel

- Hepatitis B-Hib

- COMVAX

- Hib-MenCY

- MenHibrix

COMVAX

- Hepatitis B-Hib combination

- Use when either antigen is indicated

- Cannot use before 6 weeks of age

- May be used in infants whose mothers are HBsAg positive or status is not known

Pentacel

- Contains lyophilized Hib (ActHIB) vaccine that is reconstituted with a liquid DTaP-IPV solution

- Approved for doses 1 through 4 among children 6 weeks through 4 years of age

- The DTaP-IPV solution should not be used separately (i.e., only use to reconstitute the Hib component)

Three combination vaccines that contain H. influenzae type b are licensed and available in the United States-DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel, Sanofi Pasteur), Hepatitis B-Hib (COMVAX, Merck), and Hib-MenCY (MenHibrix, GlaxoSmithKline). A fourth combination, TriHiBit, is no longer available in the U.S.

HepB-Hib-PRP-OMP (COMVAX)

COMVAX (Merck) is a combination hepatitis B-Hib vaccine. COMVAX is licensed for use when either or both antigens are indicated. However, because of the potential of immune tolerance to the Hib antigen, COMVAX should not be used in infants younger than 6 weeks of age (i.e., the birth dose of hepatitis B, or a dose at 1 month of age, if the infant is on a 0-1-6-month schedule). Although COMVAX is not licensed for infants whose mothers are known to be hepatitis B surface antigen positive (i.e., acute or chronic infection with hepatitis B virus), the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has approved off-label use of COMVAX [8 pages] for these infants. COMVAX contains the same dose of Merck’s hepatitis B vaccine recommended for these infants, so response to the hepatitis B component of COMVAX should be adequate.

Recommendations for spacing and timing of COMVAX are the same as those for the individual antigens. In particular, the third dose must be given at 12 months of age or older and at least 2 months after the second dose, as recommended for PRP-OMP. Comvax will be removed from existing contracts and pricing programs in early 2015.

DTaP-IPV-Hib-PRP-T (Pentacel)

Pentacel (Sanofi Pasteur) is a combination vaccine that contains lyophilized Hib (ActHIB) vaccine that is reconstituted with a liquid DTaP-IPV solution. Pentacel is licensed by FDA for doses 1 through 4 of the DTaP series among children 6 weeks through 4 years of age. Pentacel should not be used for the fifth dose of the DTaP series, or for children 5 years or older regardless of the number of prior doses of the component vaccines.

The DTaP-IPV solution is licensed only for use as the diluent for the lyophilized Hib component and should not be used separately. If the DTaP-IPV solution is inadvertently administered without being used to reconstitute the Hib component the DTaP and IPV doses can be counted as valid. However, PRP-T (ActHIB) must be reconstituted only with the DTaP-IPV diluent supplied in the Pentacel package, or with a specific 0.4% sodium chloride ActHIB diluent. If DTaP-IPV diluent is not available then the provider must contact the manufacturer (Sanofi Pasteur) to obtain the ActHIB diluent. Any dose of ActHIB reconstituted with a diluent other than DTaP-IPV or specific ActHIB diluent should not be counted as valid and must be repeated.

Hib-MenCY (MenHibrix)

MenHibrix

- Approved as a 4-dose series

- Infants at increased risk for meningoccal disease should be vaccinated with a 4-dose series

MenHibrix is lyophilized and should be reconstituted with a 0.9% saline diluent. MenHibrix is approved as a four dose series for children at 2, 4, 6, and 12 through 18 months. MenHibrix may be used in any infant for routine vaccination against Hib. Infants at increased risk for meningococcal disease should be vaccinated with a 4-dose series of MenHibrix. MenHibrix is not recommended for routine meningococcal vaccination for infants who are not at increased risk for meningococcal disease. See further recommendations for the MenCY component of MenHibrix.

Contraindications and Precautions to Vaccination

Haemophilus influenzae type b Vaccine Contraindications and Precautions

- Severe allergic reaction to vaccine component or following a prior dose

- Moderate or severe acute illness

- Age younger than 6 weeks

Vaccination with Hib conjugate vaccine is contraindicated for persons known to have experienced a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) to a vaccine component or following a prior dose. Vaccination should be delayed for children with moderate or severe acute illnesses. Minor illnesses (e.g., mild upper respiratory infection) are not contraindications to vaccination. Hib conjugate vaccines are contraindicated for children younger than 6 weeks of age because of the potential for development of immunologic tolerance.

Contraindications and precautions for the use of Pentacel and COMVAX are the same as those for its individual component vaccines (i.e., DTaP, Hib, IPV, and hepatitis B).

Adverse Reactions Following Vaccination

Adverse reactions following Hib conjugate vaccines are not common. Swelling, redness, or pain have been reported in 5%-30% of recipients and usually resolve within 12-24 hours. Systemic reactions such as fever and irritability are infrequent. Serious reactions are rare.

Haemophilus influenzae type b Vaccine Adverse Reactions

- Swelling, redness, or pain in 5%-30% of recipients

- Systemic reactions infrequent

- Serious adverse reactions rare

All serious adverse events that occur after receipt of any vaccine should be reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS).

Vaccine Storage and Handling

Hib vaccine should be maintained at refrigerator temperature between 35°F and 46°F (2°C and 8°C). Manufacturer package inserts contain additional information. For complete information on best practices and recommendations please refer to CDC’s Vaccine Storage and Handling Toolkit [4.33 MB, 109 pages].

Surveillance and Reporting of Hib Disease

Invasive Hib disease is a reportable condition in most states. All healthcare personnel should report any case of invasive Hib disease to local and state health departments.

Acknowledgement

The editors thank Dr. Elizabeth Briere, CDC, for her assistance in updating this chapter.

Selected References

- MacNeil JR et al; Current Epidemiology and Trends in Invasive Haemophilus influenzae Disease - United States, 1989-2008. Clinical Infectious Diseases; 2011;53(12):1230-6.

- Briere E., Jackson, ML, Shah S., et al. Haemophilus influenzae Type b Disease and Vaccine Booster Dose Deferral, United States, 1998-2009. Pediatrics 2012;130:414-20

- Livorsi DJ, Macneil JR, Cohn AC, et al. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae in the United States, 1999-2008: Epidemiology and outcomes. J Infect. 2012 Aug 15. [Epub ahead of print]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Haemophilus influenzae infections. In: Pickering L, Baker C, Kimberlin D, Long S, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012345-352.

- Bisgard KM, Kao A, Leake J, et al. Haemophilus influenzae invasive disease in the United States, 1994-1995: near disappearance of a vaccine-preventable childhood disease. Emerg Infect Dis 1998;4:229-37.

- CDC. Haemophilus b conjugate vaccines for prevention of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among infants and children two months of age and older: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 1991;40(No. RR-1):1-7.

- CDC. Progress toward elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among infants and children—United States, 1998-2000. MMWR 2002;51:234-37.

- CDC. Haemophilus influenzae invasive disease among children aged <5 years—California, 1990-1996. MMWR 1998;47:737-40.

- CDC. Licensure of a Haemophilus influenzae Type b (Hib) Vaccine (Hiberix) and Updated Recommendations for Use of Hib Vaccine. MMWR 2009;58:1008-9.

- Decker MD, Edwards KM. Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines: history, choice and comparisons. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998;17:S113-16.

- Orenstein WA, Hadler S, Wharton M. Trends in vaccine-preventable diseases. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 1997;8:23-33.

- Page last reviewed: November 15, 2016

- Page last updated: September 29, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir