Diphtheria

On this Page

Diphtheria is an acute, toxin-mediated disease caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae. The name of the disease is derived from the Greek diphthera, meaning leather hide. The disease was described in the 5th century BCE by Hippocrates, and epidemics were described in the 6th century AD by Aetius. The bacterium was first observed in diphtheritic membranes by Klebs in 1883 and cultivated by Löffler in 1884. Antitoxin was invented in the late 19th century, and toxoid was developed in the 1920s.

Corynebacterium diphtheriae

Diphtheria

- Greek diphthera (leather hide)

- Recognized by Hippocrates in 5th century BCE

- Epidemics described in 6th century

- C. diphtheriae described by Klebs in 1883

- Toxoid developed in 1920s

Corynebacterium diphtheria

- Aerobic gram-positive bacillus

- Toxin production occurs only when C. diphtheriae infected by virus (phage) carrying tox gene

- If isolated, must be distinguished from normal diphtheroid

C. diphtheriae is an aerobic gram-positive bacillus. Toxin production (toxigenicity) occurs only when the bacillus is itself infected (lysogenized) by a specific virus (bacteriophage) carrying the genetic information for the toxin (tox gene). Only toxigenic strains can cause severe disease.

Culture of the organism requires selective media containing tellurite. If isolated, the organism must be distinguished in the laboratory from other Corynebacterium species that normally inhabit the nasopharynx and skin (e.g., diphtheroids).

C. diphtheriae has four biotypes—gravis, intermedius, mitis and belfanti. All strains may produce toxin and can cause severe disease. All isolates of C. diphtheriae should be tested for toxigenicity.

Pathogenesis

Susceptible persons may acquire toxigenic diphtheria bacilli in the nasopharynx. The organism produces a toxin that inhibits cellular protein synthesis and is responsible for local tissue destruction and pseudomembrane formation. The toxin produced at the site of the membrane is absorbed into the bloodstream and then distributed to the tissues of the body. The toxin is responsible for the major complications of myocarditis and neuritis and can also cause low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia) and protein in the urine (proteinuria).

Non-toxin producing strains may cause mild to moderate pharyngitis but are not associated with formation of a pseudomembrane. While rare severe cases have been reported, these may actually have been caused by toxigenic strains that were not detected because of inadequate culture sampling.

Clinical Features

Diphtheria Clinical Features

- Incubation period 2-5 days (range, 1-10 days)

- May involve any mucous membrane

- Classified based on site of disease

- anterior nasal

- pharyngeal and tonsillar

- laryngeal

- cutaneous

- ocular

- genital

Pharyngeal and Tonsillar Diphtheria

- Insidious onset of pharyngitis

- Within 2-3 days membrane forms

- Membrane may cause respiratory obstruction

- Fever usually not high but patient appears toxic

The incubation period of diphtheria is 2-5 days (range, 1-10 days).

Disease can involve almost any mucous membrane. For clinical purposes, it is convenient to classify diphtheria into a number of manifestations, depending on the anatomic site of disease.

Anterior Nasal Diphtheria

The onset of anterior nasal diphtheria is indistinguishable from that of the common cold and is usually characterized by a mucopurulent nasal discharge (containing both mucus and pus) which may become blood-tinged. A white membrane usually forms on the nasal septum. The disease is usually fairly mild because of apparent poor systemic absorption of toxin in this location, and it can be terminated rapidly by diphtheria antitoxin and antibiotic therapy.

Pharyngeal and Tonsillar Diphtheria

The most common sites of diphtheria infection are the pharynx and the tonsils. Infection at these sites is usually associated with substantial systemic absorption of toxin. The onset of pharyngitis is insidious. Early symptoms include malaise, sore throat, anorexia, and low-grade fever (<101°F). Within 2-3 days, a bluish-white membrane forms and extends, varying in size from covering a small patch on the tonsils to covering most of the soft palate. Often by the time a physician is contacted, the membrane is greyish-green, or black if bleeding has occurred. There is a minimal amount of mucosal erythema surrounding the membrane. The pseudomembrane is firmly adherent to the tissue, and forcible attempts to remove it cause bleeding. Extensive pseudomembrane formation may result in respiratory obstruction.

While some patients may recover at this point without treatment, others may develop severe disease. Fever is usually not high, even though the patient may appear quite toxic. Patients with severe disease may develop marked edema of the submandibular areas and the anterior neck along with lymphadenopathy, giving a characteristic “bullneck” appearance. If enough toxin is absorbed, the patient may develop severe prostration, striking pallor, rapid pulse, stupor, and coma, and may even die within 6 to 10 days.

Laryngeal Diphtheria

Laryngeal diphtheria can be either an extension of the pharyngeal form or can involve only this site. Symptoms include fever, hoarseness, and a barking cough. The membrane can lead to airway obstruction, coma, and death.

Cutaneous (Skin) Diphtheria

In the United States, cutaneous diphtheria has been most often associated with homeless persons. Skin infections are quite common in the tropics and are probably responsible for the high levels of natural immunity found in these populations. Skin infections may be manifested by a scaling rash or by ulcers with clearly demarcated edges and membrane, but any chronic skin lesion may harbor C. diphtheriae along with other organisms. Generally, the organisms isolated from cases in the United States were nontoxigenic. The severity of the skin disease with toxigenic strains appears to be less than from other sites. Cutaneous diphtheria is no longer reported to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System in the United States.

Rarely, other sites of involvement include the mucous membranes of the conjunctiva and vulvovaginal area, as well as the external auditory canal.

Complications

Diphtheria Complications

- Most attributable to toxin

- Severity generally related to extent of local disease

- Most frequent complications are myocarditis and neuritis

- Death occurs in 5%-10%

Most complications of diphtheria, including death, are attributable to effects of the toxin. The severity of the disease and complications are generally related to the extent of local disease. The toxin, when absorbed, affects organs and tissues distant from the site of invasion. The most frequent complications of diphtheria are myocarditis and neuritis.

Myocarditis may present as abnormal cardiac rhythms and can occur early in the course of the illness or weeks later, and can lead to heart failure. If myocarditis occurs early, it is often fatal.

Neuritis most often affects motor nerves and usually resolves completely. Paralysis of the soft palate is most frequent during the third week of illness. Paralysis of eye muscles, limbs, and diaphragm can occur after the fifth week. Secondary pneumonia and respiratory failure may result from diaphragmatic paralysis.

Other complications include otitis media and respiratory insufficiency due to airway obstruction, especially in infants.

Death

The overall case-fatality rate for diphtheria is 5%-10%, with higher death rates (up to 20%) among persons younger than 5 and older than 40 years of age. The case-fatality rate for diphtheria has changed very little during the last 50 years.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Diagnosis of diphtheria is usually made on the basis of clinical presentation since it is imperative to begin presumptive therapy quickly.

Culture of the lesion is done to confirm the diagnosis. It is critical to take a swab of the pharyngeal area, especially any discolored areas, ulcerations, and tonsillar crypts. Culture medium containing tellurite is preferred because it provides a selective advantage for the growth of this organism. If diphtheria bacilli are isolated, they must be tested for toxin production.

A blood agar plate is also inoculated for detection of hemolytic streptococcus. Gram stain and Kenyon stain of material from the membrane itself can be helpful when trying to confirm the clinical diagnosis. The Gram stain may show multiple club-shaped forms that look like Chinese characters. Other Corynebacterium species (diphtheroids) that can normally inhabit the throat may confuse the interpretation of direct stain. However, treatment should be started if clinical diphtheria is suggested, even in the absence of a Gram stain.

In the event that prior antibiotic therapy may have impeded a positive culture in a suspect diphtheria case, three sources of evidence can aid in presumptive diagnosis: 1) a positive polymerase chain reaction test for diphtheria tox genes, or 2) isolation of C. diphtheriae from cultures of specimens from close contacts, or 3) a low nonprotective diphtheria antibody titer (less than 0.1 IU) in serum obtained prior to antitoxin administration. This is done by commercial laboratories and requires several days. To isolate C. diphtheriae from carriers, it is best to inoculate a Löffler or Pai slant with the throat swab. After an incubation period of 18-24 hours, growth from the slant is used to inoculate a medium containing tellurite.

Medical Management

Diphtheria Antitoxin

Diphtheria Antitoxin

- Produced in horses

- First used in the U.S. in the 1890s

- Used only for treatment of diphtheria

- Neutralizes only unbound toxin

Diphtheria antitoxin, produced in horses, was used for treatment of diphtheria in the United States since the 1890s. It is not indicated for prophylaxis of contacts of diphtheria patients. Since 1997, diphtheria antitoxin has been available only from CDC, through an Investigational New Drug (IND) protocol. Diphtheria antitoxin does not neutralize toxin that is already fixed to tissues, but it will neutralize circulating (unbound) toxin and prevent progression of disease. The patient must be tested for sensitivity before antitoxin is given. Consultation on the use of diphtheria antitoxin is available through the duty officer at the CDC through CDC’s Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100.

After a provisional clinical diagnosis is made, appropriate specimens should be obtained for culture and the patient placed in isolation. Persons with suspected diphtheria should be given diphtheria antitoxin and antibiotics in adequate dosage. Respiratory support and airway maintenance should also be administered as needed.

Antibiotics

The antibiotics of choice are erythromycin (500 mg four times daily for 14 days) or procaine penicillin G (300,000 units every 12 hours for patients ≤10 kg and 600,000 units every 12 hours for patients >10 kg intramuscularly) until the patient can take oral medicine, followed by oral penicillin V (250 mg four times daily) for a total treatment course of 14 days. The disease is usually not contagious 48 hours after antibiotics are instituted. Elimination of the organism should be documented by two consecutive negative cultures after therapy is completed.

Preventive Measures

For close contacts, especially household contacts, a diphtheria booster, appropriate for age, should be given. Contacts should also receive antibiotics—benzathine penicillin G (600,000 units for persons younger than 6 years old and 1,200,000 units for those 6 years old and older) or a 7- to 10-day course of oral erythromycin (40 mg/kg/day for children and 1 g/day for adults). For compliance reasons, if surveillance of contacts cannot be maintained, they should receive benzathine penicillin G. Identified carriers in the community should also receive antibiotics. Maintain close surveillance and begin antitoxin at the first signs of illness.

Contacts of cutaneous diphtheria should be treated as described above; however, if the strain is shown to be nontoxigenic, investigation of contacts should be discontinued.

Epidemiology

Diphtheria Epidemiology

- Reservoir

- human carriers

- usually asymptomatic

- Transmission

- respiratory

- skin and fomites rarely

- Temporal pattern

- winter and spring

- Communicability

- without antibiotics, seldom more than 4 weeks

Occurrence

Diphtheria occurs worldwide, particularly in tropical countries. Diphtheria is a rare disease in industrialized countries including the United States. In the United States during the pre-vaccine era, the highest incidence was in the Southeast during the winter.

Reservoir

Human carriers are the reservoir for C. diphtheriae and are usually asymptomatic. In outbreaks, high percentages of children are found to be transient carriers.

Transmission

Transmission is most often person-to-person spread from the respiratory tract. Rarely, transmission may occur from skin lesions or articles soiled with discharges from lesions of infected persons (fomites).

Temporal Pattern

In temperate areas, diphtheria most frequently occurs during winter and spring.

Communicability

Transmission may occur as long as virulent bacilli are present in discharges and lesions. The time is variable, but without antibiotics, organisms usually persist 2 weeks or less and seldom more than 4 weeks. Chronic carriers may shed organisms for 6 months or more. Effective antibiotic therapy promptly terminates shedding.

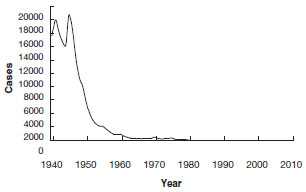

Diphtheria - United States

1940-2011

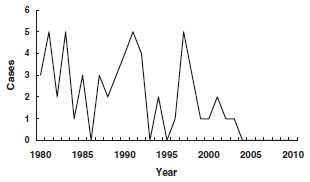

Diphtheria - United States

1980-2011

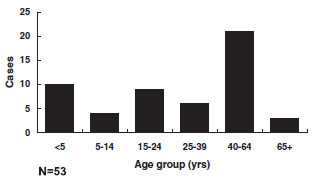

Diphtheria - Age Distribution of Reported Cases, United States

Secular Trends in the United States

Globally, diphtheria was once a major cause of morbidity and mortality among children. In England and Wales during the 1930s, diphtheria was among the top three causes of death for children younger than 15 years of age. During the 1920s in the United States, 100,000-200,000 cases of diphtheria (140-150 cases per 100,000 population) and 13,000-15,000 deaths were reported each year. In 1921, a total of 206,000 cases and 15,520 deaths were reported. The number of cases gradually declined to about 19,000 in 1945 (15 per 100,000 population). A more rapid decrease began with the widespread use of diphtheria toxoid in the late 1940s.

From 1970 through 1979, an average of 196 cases per year were reported. This included a high proportion of cutaneous cases from an outbreak in Washington State. Beginning in 1980, all cutaneous cases were excluded from reporting. Diphtheria was seen most frequently in Native Americans and persons in lower socioeconomic strata.

From 1980 through 2011, 55 cases of diphtheria were reported in the United States, an average of 1 or 2 per year (range, 0-5 cases per year). Only 5 cases have been reported since 2000.

Of 53 reported cases with known patient age since 1980, 34 (64%) were in persons 20 years of age or older; 41% of cases were among persons 40 years of age or older. Most cases have occurred in unimmunized or inadequately immunized persons. The current age distribution of cases corroborates the finding of inadequate levels of circulating antitoxin in many adults (up to 60% with less than protective levels).

Although diphtheria disease is rare in the United States, it appears that toxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae continues to circulate in areas of the country with previously endemic diphtheria. In 1996, 8 isolates of toxigenic C. diphtheriae were obtained from persons in a Native American community in South Dakota. None of the infected persons had classic diphtheria disease, although five had either pharyngitis or tonsillitis. The presence of toxigenic C. diphtheriae in this community is a good reminder for providers not to let down their guard against this organism.

Diphtheria continues to occur in other parts of the world. A major epidemic of diphtheria occurred in countries of the former Soviet Union beginning in 1990. By 1994, the epidemic had affected all 15 Newly Independent States (NIS). More than 157,000 cases and more than 5,000 deaths were reported. In the 6 years from 1990 through 1995, the NIS accounted for more than 90% of all diphtheria cases reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) from the entire world. In some NIS countries, up to 80% of the epidemic diphtheria cases have been among adults. The outbreak and the age distribution of cases are believed to be due to several factors, including a lack of routine immunization of adults in these countries. Globally, reported cases of diphtheria have declined from 11,625 in 2000 to 4,880 cases in 2011.

Diphtheria Toxoid

Minimum Intervals and Ages

- Converted from toxin to toxoid

- Schedule

- 3 or 4 doses plus booster

- booster every 10 years

- Efficacy

- approximately 95%

- Duration

- approximately 10 years

- Should be administered with tetanus toxoid as DTaP, DT, Td, or Tdap

Characteristics

Beginning in the early 1900s, prophylaxis was attempted with toxin-antitoxin mixtures. Toxoid was developed around 1921 but was not widely used until the early 1930s. It was incorporated with tetanus toxoid and pertussis vaccine and became routinely used in the 1940s.

Diphtheria toxoid is produced by growing toxigenic C. diphtheriae in liquid medium. The filtrate is incubated with formaldehyde to convert toxin to toxoid and is then adsorbed onto an aluminum salt.

Single-antigen diphtheria toxoid is not available. Diphtheria toxoid is combined with tetanus toxoid as pediatric diphtheria-tetanus toxoid (DT) or adult tetanus-diphtheria (Td), and with both tetanus toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine as DTaP and Tdap. Diphtheria toxoid is also available as combined DTaP-HepB-IPV (Pediarix) and DTaP-IPV/Hib (Pentacel)—see Pertussis chapter for more information. Pediatric formulations (DT and DTaP) contain a similar amount of tetanus toxoid as adult Td, but contain 3 to 4 times as much diphtheria toxoid. Children younger than 7 years of age should receive either DTaP or pediatric DT. Persons 7 years of age or older should receive the adult formulation (adult Td), even if they have not completed a series of DTaP or pediatric DT. Two brands of Tdap are available—Boostrix (approved for persons 10 years of age or older) and Adacel (approved for persons 10 through 64 years of age). DTaP and Tdap vaccines do not contain thimerosal as a preservative.

Routine DTaP Primary Vaccination Schedule

| Dose | Age | Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Primary 1 | 2 months | --- |

| Primary 2 | 4 months | 4 weeks |

| Primary 3 | 6 months | 4 weeks |

| Primary 4 | 15-18 months | 6 months |

Children Who Receive DT

- The number of doses of DT needed to complete the series depends on the child’s age at the first dose:

- if first dose given at younger than 12 months of age, 4 doses are recommended

- if first dose given at 12 months or older, 3 doses complete the primary series

Tetanus, Diphtheria and Pertussis Booster Doses

- 4 through 6 years of age, before entering school (DTaP)

- 11 or 12 years of age (Tdap)

- Every 10 years thereafter (Td)

Routine Td Schedule for Unvaccinated Persons 7 Years of Age and Older

| Dose* | Interval |

|---|---|

| Primary 1 | --- |

| Primary 2 | 4 weeks |

| Primary 3 | 6 to 12 months |

Booster dose every 10 years

*ACIP recommends that one of these doses (preferably the first) be administered as Tdap

Immunogenicity and Vaccine Efficacy

After a primary series of three properly spaced diphtheria toxoid doses in adults or four doses in infants, a protective level of antitoxin (defined as greater than 0.1 IU of antitoxin/mL) is reached in more than 95%. Diphtheria toxoid has been estimated to have a clinical efficacy of 97%.

Vaccination Schedule and Use

DTaP (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine) is the vaccine of choice for children 6 weeks through 6 years of age. The usual schedule is a primary series of 4 doses at 2, 4, 6, and 15-18 months of age. The first, second, and third doses of DTaP should be separated by a minimum of 4 weeks. The fourth dose should follow the third dose by no less than 6 months, and should not be administered before 12 months of age.

If a child has a valid contraindication to pertussis vaccine, pediatric DT should be used to complete the vaccination series. If the child was younger than 12 months old when the first dose of DT was administered (as DTP, DTaP, or DT), the child should receive a total of four primary DT doses. If the child was 12 months of age or older at the time the first dose of DT was administered, three doses (third dose 6-12 months after the second) complete the primary DT series.

If the fourth dose of DT, DTP or DTaP is administered before the fourth birthday, a booster (fifth) dose is recommended at 4 through 6 years of age. The fifth dose is not required if the fourth dose was given on or after the fourth birthday.

Vaccines containing reduced diphtheria (i.e., Td and Tdap) are indicated for children 7 years and older and for adults. A primary series is three or four doses, depending on whether the person has received prior doses of diphtheria-containing vaccine, and the age these doses were administered. The number of doses recommended for children who received one or more doses of DTP, DTaP, or DT before age 7 years is discussed above. For unvaccinated persons 7 years and older (including persons who cannot document prior vaccination), the primary series is three doses. The first two doses should be separated by at least 4 weeks, and the third dose given 6 to 12 months after the second. ACIP recommends that one of these doses (preferably the first) be administered as Tdap. A booster dose of Td should be given every 10 years. Persons who have never received Tdap should be given a dose of Tdap as one of these boosters. Refer to the pertussis chapter for more information about Tdap.

Interruption of the recommended schedule or delay of subsequent doses does not reduce the response to the vaccine when the series is finally completed. There is no need to restart a series regardless of the time elapsed between doses.

Diphtheria disease might not confer immunity. Persons recovering from diphtheria should begin or complete active immunization with diphtheria toxoid during convalescence.

Contraindications and Precautions to Vaccination

Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids Contraindications and Precautions

- Severe allergic reaction to vaccine component or following a prior dose

- Moderate or severe acute illness

Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids Adverse Events

- Reports of severe systemic adverse events (urticaria, anophylaxis, neurologic complications) are rare

Diphtheria and Tetanus Toxoids Adverse Reactions

- Local reactions (erythema, induration) are common

- Fever and systemic symptoms not common

- Exaggerated local reactions (Arthus-type) occasionally reported

Persons with a history of a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) to a vaccine component or following a prior dose should not receive additional doses of diphtheria toxoid. Diphtheria toxoid should be deferred for those persons who have moderate or severe acute illness, but persons with minor illness may be vaccinated. Immunosuppression and pregnancy are not contraindications to receiving diphtheria toxoid. See pertussis chapter for additional information on contraindications and precautions to Tdap.

Adverse Events Following Vaccination

Rarely, severe systemic adverse events, such as generalized urticaria, anaphylaxis, or neurologic complications have been reported following administration of diphtheria toxoid.

Adverse Reactions Following Vaccination

Local reactions, generally erythema and induration with or without tenderness, are common after the administration of vaccines containing diphtheria toxoid. Local reactions are usually self-limited and require no therapy. A nodule may be palpable at the injection site for several weeks. Abscess at the site of injection has been reported. Fever and other systemic symptoms are not common.

Exaggerated local (Arthus-type) reactions are occasionally reported following receipt of a diphtheria- or tetanus-containing vaccine. These reactions present as extensive painful swelling, often from shoulder to elbow. They generally begin 2-8 hours after injections and are reported most often in adults, particularly those who have received frequent doses of diphtheria or tetanus toxoid. Persons experiencing these severe reactions usually have very high serum antitoxin levels; they should not be given further routine or emergency booster doses of Td more frequently than every 10 years. Less severe local reactions may occur in persons who have multiple prior boosters.

Vaccine Storage and Handling

All diptheria-toxoid containing vaccines should be maintained at refrigerator temperature between 35°F and 46°F (2°C and 8°C). Manufacturer package inserts contain additional information. For complete information on best practices and recommendations please refer to CDC’s Vaccine Storage and Handling Toolkit [4.33 MB, 109 pages].

Suspect Case Investigation and Control

Immediate action on all highly suspect cases is warranted until they are shown not to be caused by toxigenic C. diphtheriae. The following action should also be taken for any toxigenic C. diphtheriae carriers who are detected.

- Contact state health department or CDC.

- Obtain appropriate cultures and preliminary clinical and epidemiologic information (including vaccine history).

- Begin early presumptive treatment with antitoxin and antibiotics. Impose strict isolation until at least two cultures are negative 24 hours after antibiotics were discontinued.

- Identify close contacts, especially household members and other persons directly exposed to oral secretions of the patient. Culture all close contacts, regardless of their immunization status. Ideally, culture should be from both throat and nasal swabs. After culture, all contacts should receive antibiotic prophylaxis. Inadequately immunized contacts should receive DTaP/DT/Td/Tdap boosters. If fewer than three doses of diphtheria toxoid have been given, or vaccination history is unknown, an immediate dose of diphtheria toxoid should be given and the primary series completed according to the current schedule. If more than 5 years have elapsed since administration of diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine, a booster dose should be given. If the most recent dose was within 5 years, no booster is required (see the ACIP’s 1991 Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis: Recommendations for Vaccine Use and Other Preventive Measures for schedule for children younger than 7 years of age). Unimmunized contacts should start a course of DTaP/DT/Td vaccine and be monitored closely for symptoms of diphtheria for 7 days.

- Treat any confirmed carrier with an adequate course of antibiotic, and repeat cultures at a minimum of 2 weeks to ensure eradication of the organism. Persons who continue to harbor the organism after treatment with either penicillin or erythromycin should receive an additional 10-day course of erythromycin and should submit samples for follow-up cultures.

- Treat any contact with antitoxin at the first sign of illness.

Acknowledgment

The editors thank Dr. Cindy Weinbaum, CDC for her assistance in updating this chapter.

Selected References

- CDC. Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis: Recommendations for vaccine use and other preventive measures: recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP). MMWR 1991;40(No. RR-10):1-28.

- CDC. Pertussis vaccination: use of acellular pertussis vaccines among infants and young children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 1997;46 (No. RR-7):1-25.

- CDC. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adolescents: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2006;55(No. RR-3):1-34.

- CDC. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adults: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and Recommendation of ACIP, supported by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), for Use of Tdap Among Health-Care Personnel. MMWR 2006;55(No. RR-17):1-33.

- Farizo KM, Strebel PM, Chen RT, Kimbler A, Cleary TJ, Cochi SL. Fatal respiratory disease due to Corynebacterium diphtheriae: case report and review of guidelines for management, investigation, and control. Clin Infect Dis 1993;16:59-68.

- Vitek CR, Wharton M. Diphtheria in the former Soviet Union: reemergence of a pandemic disease. Emerg Infect Dis 1998;4:539-50.

- Vitek CR, Wharton M, Diphtheria toxoid. In Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit, PA, eds. Vaccines. 5th ed. China: Saunders, 2008:139-56.

- Page last reviewed: November 15, 2016

- Page last updated: November 9, 2015

- Content source:

ShareCompartir

ShareCompartir