Mycosis fungoides

Mycosis fungoides, also known as Alibert-Bazin syndrome[1] or granuloma fungoides, is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It generally affects the skin, but may progress internally over time. Symptoms include rash, tumors, skin lesions, and itchy skin.

| Mycosis fungoides | |

|---|---|

| Skin lesions on the knee of a 52-year-old male patient with Mycosis fungoides | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

While the cause remains unclear, most cases are not hereditary. Most cases are in people over 20 years of age, and it is more common in men than women. Treatment options include sunlight exposure, ultraviolet light, topical corticosteroids, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

Signs and symptoms

Typical visible symptoms include rash-like patches, tumors, or lesions.[2] Itching (pruritus) is common, perhaps in 20 percent of patients, but is not universal. The symptoms displayed are progressive, with early stages consisting of lesions presented as scaly patches. These lesions prefer the buttock region.[3] The later stages involve the patches evolving into plaques distributed over the entire body. The advanced stage of mycosis fungoides is characterized by generalized erythroderma, with severe pruritus and scaling.[4]

Cause

The cause of mycosis fungoides is unknown, but it is not believed to be hereditary or genetic in the vast majority of cases. One incident has been reported of a possible genetic link.[5] It is not contagious, although some research suggests that the Human T-lymphotropic virus is associated with this condition.[6]

The disease is an unusual expression of CD4 T cells, a part of the immune system. These T cells are skin-associated, meaning they are biochemically and biologically most related to the skin, in a dynamic manner. Mycosis fungoides is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), but there are many other types of CTCL that have nothing to do with mycosis fungoides and these disorders are treated differently.

Diagnosis

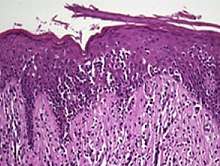

Diagnosis is sometimes difficult because the early phases of the disease often resemble eczema or even psoriasis. Several biopsies are recommended, to be more certain of the diagnosis. The criteria for the disease are established on the skin biopsy:[7]

- the superficial papillary dermis is infiltrated by a bandlike lymphocyte infiltrate

- epidermotropism

- presence of atypical "cerebriform" T-cells in the dermal and epidermal infiltrates.

Pautrier microabcesses (i.e., Aggregates of four or more atypical lymphocytes arranged in the epidermis[8]) are characteristic of the disease but are generally absent.

To stage the disease, various tests may be ordered, to assess nodes, blood and internal organs, but most patients present with disease apparently confined to the skin, as patches (flat spots) and plaques (slightly raised or 'wrinkled' spots).

Peripheral smear will often show buttock cells.[9]

Staging

Traditionally, mycosis fungoides has been divided into three stages: premycotic, mycotic and tumorous. The premycotic stage clinically presents as an erythematous (red), itchy, scaly lesion. Microscopic appearance is non-diagnostic and represented by chronic nonspecific dermatosis associated with psoriasiform changes in epidermis.

In the mycotic stage, infiltrative plaques appear and biopsy shows a polymorphous inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis that contains small numbers of frankly atypical lymphoid cells. These cells may line up individually along the epidermal basal layer. The latter finding if unaccompanied by spongiosis is highly suggestive of mycosis fungoides. In the tumorous stage a dense infiltrate of medium-sized lymphocytes with cerebroid nuclei expands the dermis.

Prognosis

A 1999 US-based study of patient records observed a 5-year relative survival rate of 77%, and a 10-year relative survival rate of 69%. After 11 years, the observed relative survival rate remained around 66%. Poorer survival is correlated with advanced age and black race. Superior survival was observed for married women compared with other gender and marital-status groups.[10]

Treatments

Mycosis fungoides can be treated in a variety of ways.[11] Common treatments include simple sunlight, ultraviolet light (mainly NB-UVB 312 nm), topical steroids, topical and systemic chemotherapies, local superficial radiotherapy, the histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat, total skin electron radiation, photopheresis and systemic therapies (e.g. interferons, retinoids, rexinoids) or biological therapies. Treatments are often used in combination.

There is limited evidence for the efficacy of topical and systemic therapies for mycosis fungoides.[12] Due to the possible adverse effects of these treatments in early disease it is recommended to begin therapy with topical and skin-directed treatments before progressing to more systemic therapies.[12] Larger and more extensive research is needed to identify effective treatment strategies for this disease.[12]

In 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted orphan drug designation for naloxone lotion, a topical opioid receptor competitive antagonist used as a treatment for pruritus in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.[13][14]

Epidemiology

It is rare for the disease to appear before age 20, and it appears to be noticeably more common in males than females, especially over the age of 50, where the incidence of the disease (the risk per person in the population) does increase. The average age of onset is between 45 and 55 years of age for patients with patch and plaque disease only, but is over 60 for patients who present with tumours, erythroderma (red skin) or a leukemic form (the Sézary syndrome). The incidence of mycosis fungoides was seen to be increasing till the year 2000 in the United States,[15] thought to be due to improvements in diagnostics. However, the reported incidence of the disease has since then remained constant,[16] suggesting another unknown reason for the jump seen before 2000.

History

Mycosis fungoides was first described in 1806 by French dermatologist Jean-Louis-Marc Alibert.[17][18] The name mycosis fungoides is very misleading—it loosely means "mushroom-like fungal disease". The disease, however, is not a fungal infection but rather a type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. It was so named because Alibert described the skin tumors of a severe case as having a mushroom-like appearance.[19]

Research

Mogamulizumab has been under development for this condition, and of January 2018 was undergoing priority review at the FDA.[20]

See also

References

- synd/98 at Who Named It?

- Cerroni, Lorenzo; Kevin Gatter; Helmut Kerl (2005). An illustrated guide to Skin Lymphomas. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4051-1376-2.

- Jawed, Sarah I.; Myskowski, Patricia L.; Horwitz, Steven; Moskowitz, Alison; Querfeld, Christiane (2014-02-01). "Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome)". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 70 (2): 223.e1–223.e17. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.08.033. ISSN 0190-9622. PMID 24438970.

- Beigi, Pooya Khan Mohammad (2017). "Diagnosis and Management". Clinician's Guide to Mycosis Fungoides. Springer International Publishing. pp. 13–18. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47907-1_4. ISBN 9783319479064. PMC 1806090.

- Shelley WB (October 1980). "Familial mycosis fungoides revisited". Archives of Dermatology. 116 (10): 1177–8. doi:10.1001/archderm.1980.01640340087024. PMID 7425665.

- Pancake BA, Zucker-Franklin D, Coutavas EE (1995). "The cutaneous T cell lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, is a human T cell lymphotropic virus-associated disease. A study of 50 patients". J Clin Invest. 95 (2): 547–54. doi:10.1172/JCI117697. PMC 295510. PMID 7860737.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Canada, editors, John P. Greer, MD, Professor, Departments of Medicine and Pediatrics, Divisions of Hermatology/Oncology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; Daniel A. Arber, MD, Professor and Vice Chair, Department of Pathology, Stanford University, Director of Anatomic and Clinical Pathology Services, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California; Bertil Glader, MD, Professor, Departments of Pediatrics and Pathology, Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, California, Lucile Packard Children's Hospital, Palo Alto, California; Alan F. List, MD, Senior Member, Department of Malignant Hematology, President and CEO, Moffit Cancer Center, Tampa Florida; Robert T. Means Jr., MD, PhD, Professor of Internal Medicine, Executive Dean, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, Kentucky; Frixos Paraskevas, MD, Professor of Internal Medicine and Immunology (Retired), University of Mantioba Medical School, Associate Member, Institute of Cell Biology-Cancer Care, Mantioba, Winnipeg, Mantioba, Canada; George M. Rodgers, MD, Professor of Medicine and Pathology, University of Utah School of Medicine, Health Sciences Center, Medical Director, Coagulation Laboratory, ARUB Laboratories, Salt Lake City, Utah; Editor Emeritus, John Foerster, MD, FRCPC, Professor and Physician Emertius, Winnipeg (2014). Wintrobe's clinical hematology (Thirteenth ed.). p. 1957. ISBN 978-1451172683.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- al.], [edited by] Ronald Hoffman ... [et (2013). Hematology : basic principles and practice (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 1288. ISBN 978-1437729283.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- O'Connell, Theodore X. (28 November 2013). USMLE Step 2 Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 240. ISBN 9780323225021.

- Weinstock, Martin A.; Reynes, Josefina F. (1999). "The changing survival of patients with mycosis fungoides". Cancer. 85 (1): 208–212. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990101)85:1<208::AID-CNCR28>3.0.CO;2-2. ISSN 0008-543X.

- Prince HM, Whittaker S, Hoppe RT (November 2009). "How I treat mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome". Blood. 114 (20): 4337–53. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-07-202895. PMID 19696197.

- Weberschock, Tobias; Strametz, Reinhard; Lorenz, Maria; Röllig, Christoph; Bunch, Charles; Bauer, Andrea; Schmitt, Jochen (2012-09-12). "Interventions for mycosis fungoides". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD008946. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008946.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 22972128.

- "Elorac, Inc. announces orphan drug designation for novel topical treatment for pruritus in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)". Archived from the original on 2010-12-30. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- Wang H, Yosipovitch G (January 2010). "New insights into the pathophysiology and treatment of chronic itch in patients with end-stage renal disease, chronic liver disease, and lymphoma". International Journal of Dermatology. 49 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04249.x. PMC 2871329. PMID 20465602.

- Morales Suárez-Varela, M. M.; Llopis González, A.; Marquina Vila, A.; Bell, J. (2000). "Mycosis fungoides: review of epidemiological observations". Dermatology. 201 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1159/000018423. ISSN 1018-8665. PMID 10971054.

- Korgavkar, Kaveri; Xiong, Michael; Weinstock, Martin (2013-11-01). "Changing incidence trends of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma". JAMA Dermatology. 149 (11): 1295–1299. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5526. ISSN 2168-6084. PMID 24005876.

- Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 1867. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- Alibert JLM (1806). Descriptions des maladies de la peau observées a l'Hôpital Saint-Louis, et exposition des meilleures méthodes suivies pour leur traitement (in French). Paris: Barrois l’ainé. p. 286. Archived from the original on 2012-12-12.

- Cerroni, 2007, p.13

- Adamson, Laurie (22 January 2018). "Mogamulizumab Receives Priority Review for CTCL - ASH Clinical News". ASH Clinical News. Archived from the original on 2018-05-10. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

Further reading

- Knowles Daniel M (2000). Neoplastic Hematopathology. Lippincott Williams Wilkins. p. 1957. ISBN 978-0-683-30246-2.

- Hwang ST, Janik JE, Jaffe ES, Wilson WH (March 2008). "Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome". Lancet. 371 (9616): 945–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60420-1. PMID 18342689.

- Duvic M, Foss FM (December 2007). "Mycosis fungoides: pathophysiology and emerging therapies". Seminars in Oncology. 34 (6 Suppl 5): S21–8. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2007.11.006. PMID 18086343.

- Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, Willemze R, Kim Y, Knobler R, Zackheim H, Duvic M, Estrach T, Lamberg S, Wood G, Dummer R, Ranki A, Burg G, Heald P, Pittelkow M, Bernengo MG, Sterry W, Laroche L, Trautinger F, Whittaker S (September 2007). "Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)". Blood. 110 (6): 1713–22. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-03-055749. PMID 17540844.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |